Thirty-five years ago Elio de Angelis lost his life after a fiery accident at Paul Ricard that should have had a less serious outcome – and from which the sport learned valuable lessons.

The death of Elio de Angelis after a crash at Paul Ricard in May 1986 demonstrated that, despite much improved car safety standards, little had changed since Roger Williamson perished in the Dutch GP some 13 years earlier.

But while the Zandvoort tragedy played out on live TV around the world, de Angelis crashed on a Wednesday morning at a quiet test day. That explains why the awful story of the chaotic circumstances that followed the accident received relatively little publicity.

Indeed in the rush to judgement after Imola 1994 many observers referenced the deaths of Gilles Villeneuve and Riccardo Paletti on race weekends in 1982 as the last tragedies that Grand Prix racing had seen, as if an accident in testing was a footnote, and somehow of less significance.

That was an injustice not only to the memory of de Angelis, but also to those who bravely fought to save him on that sad Wednesday morning in France.

A promising rookie

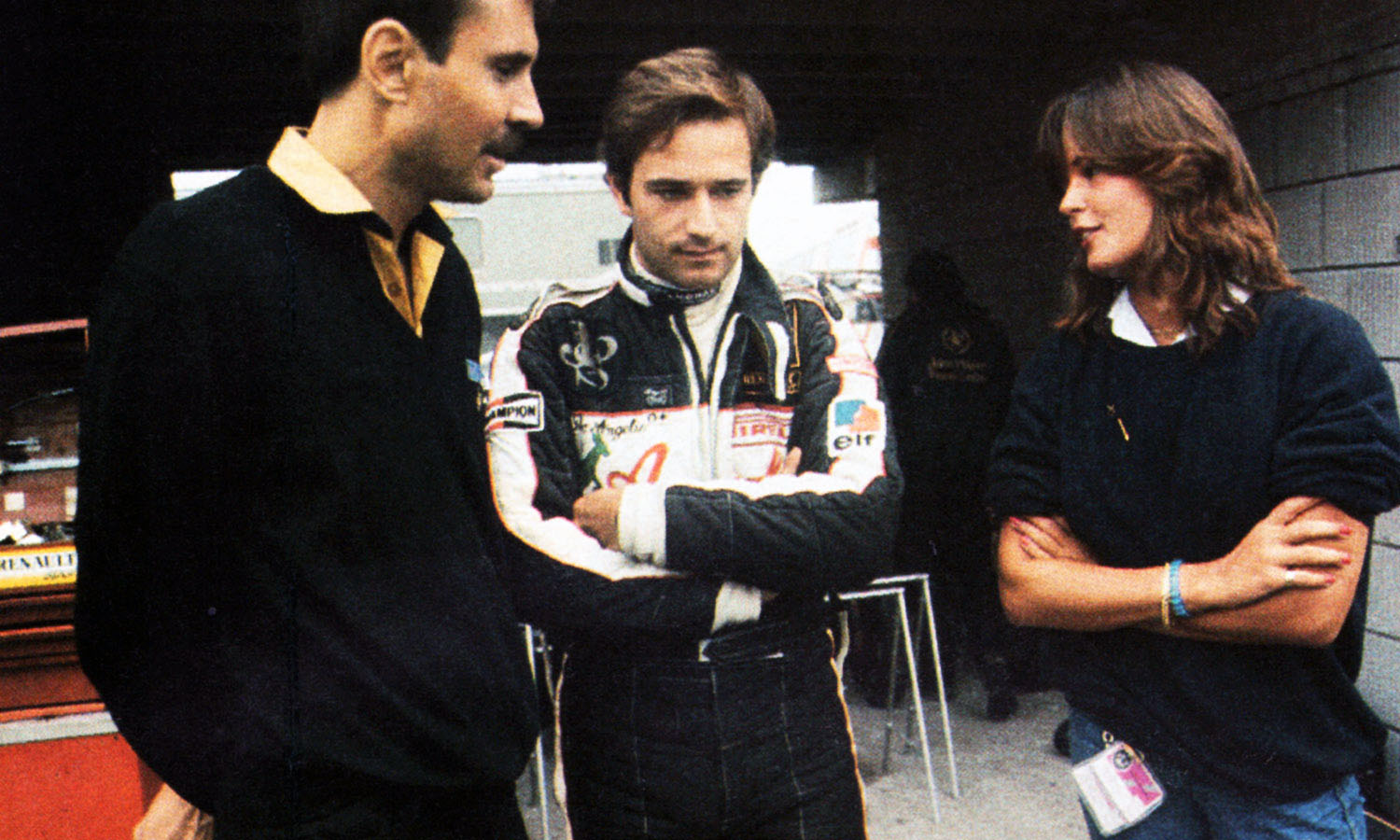

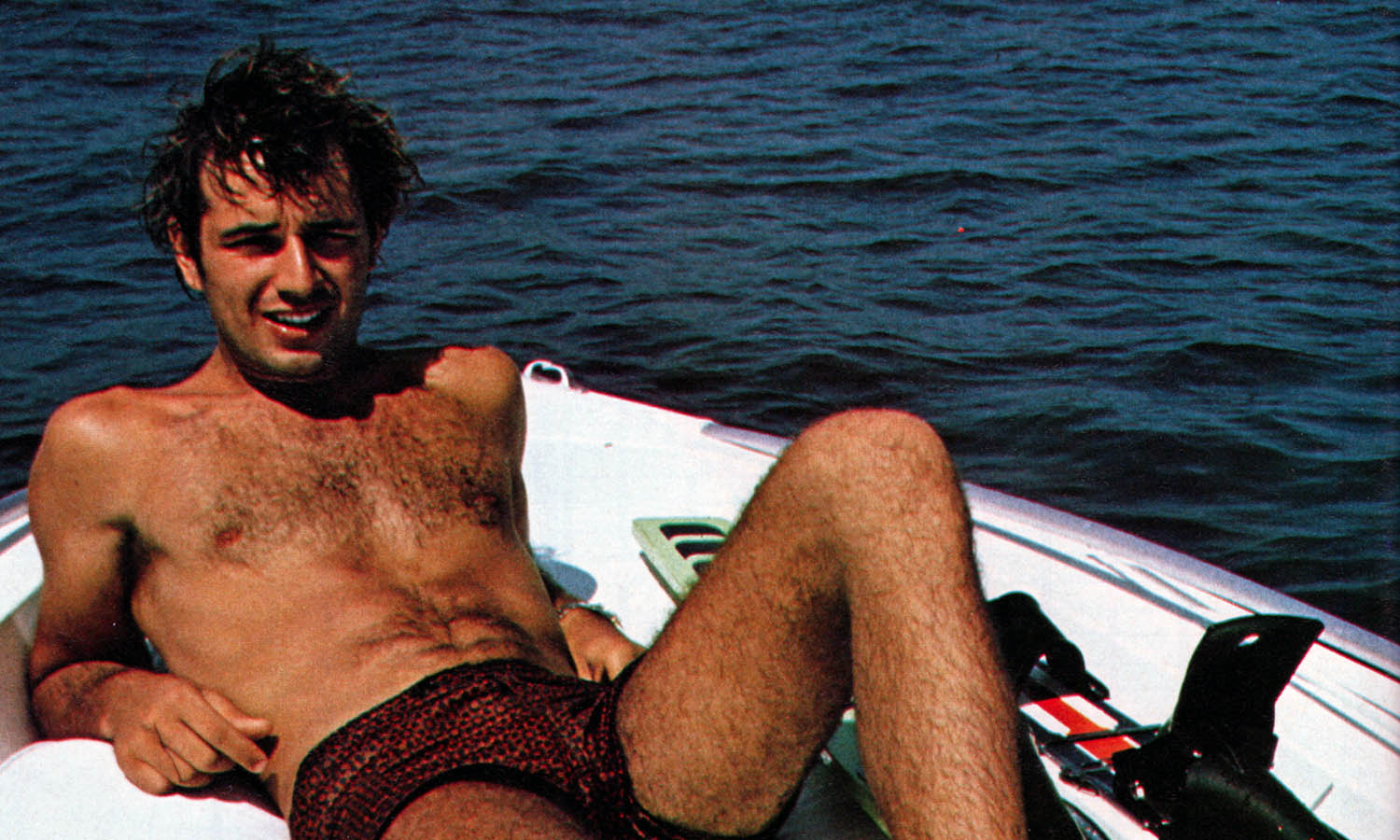

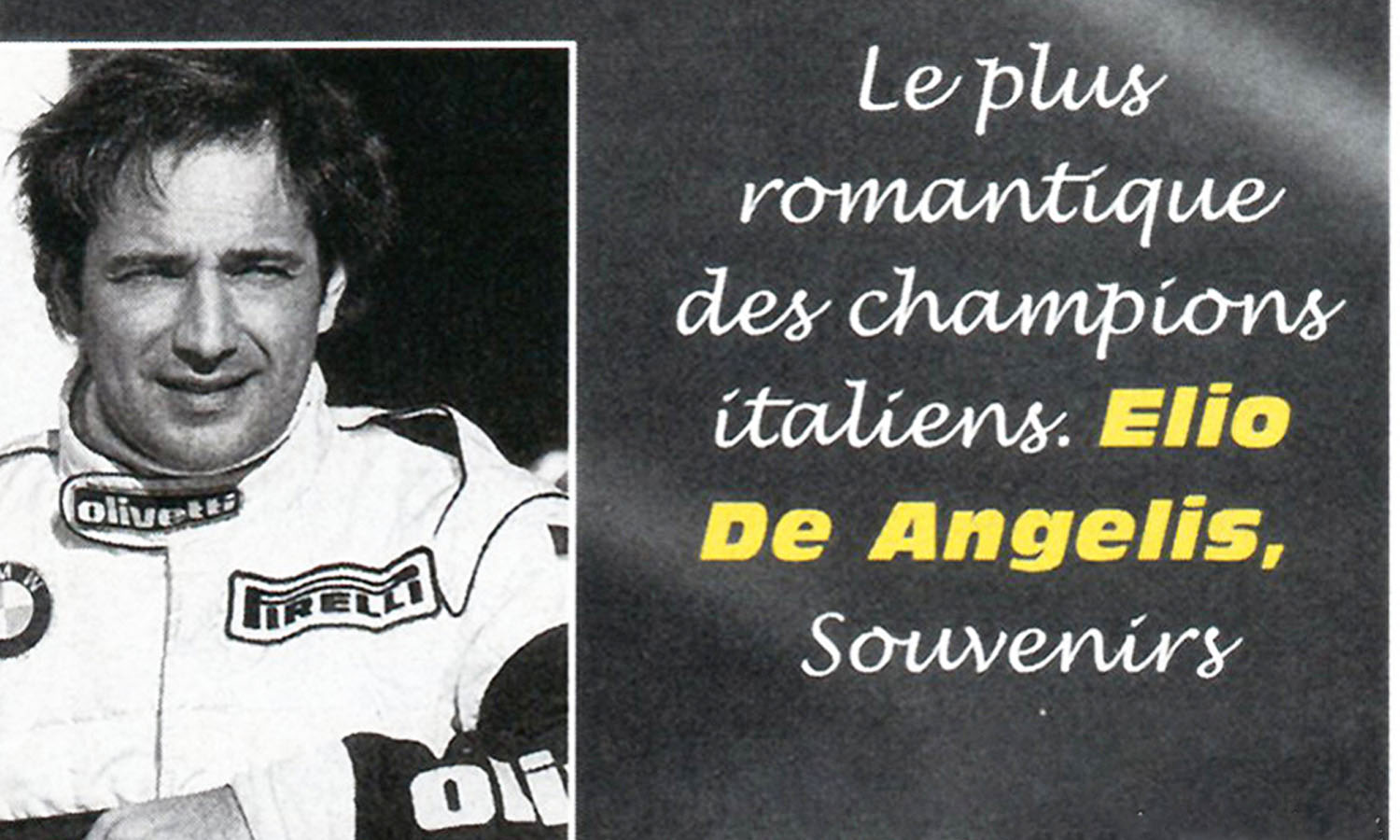

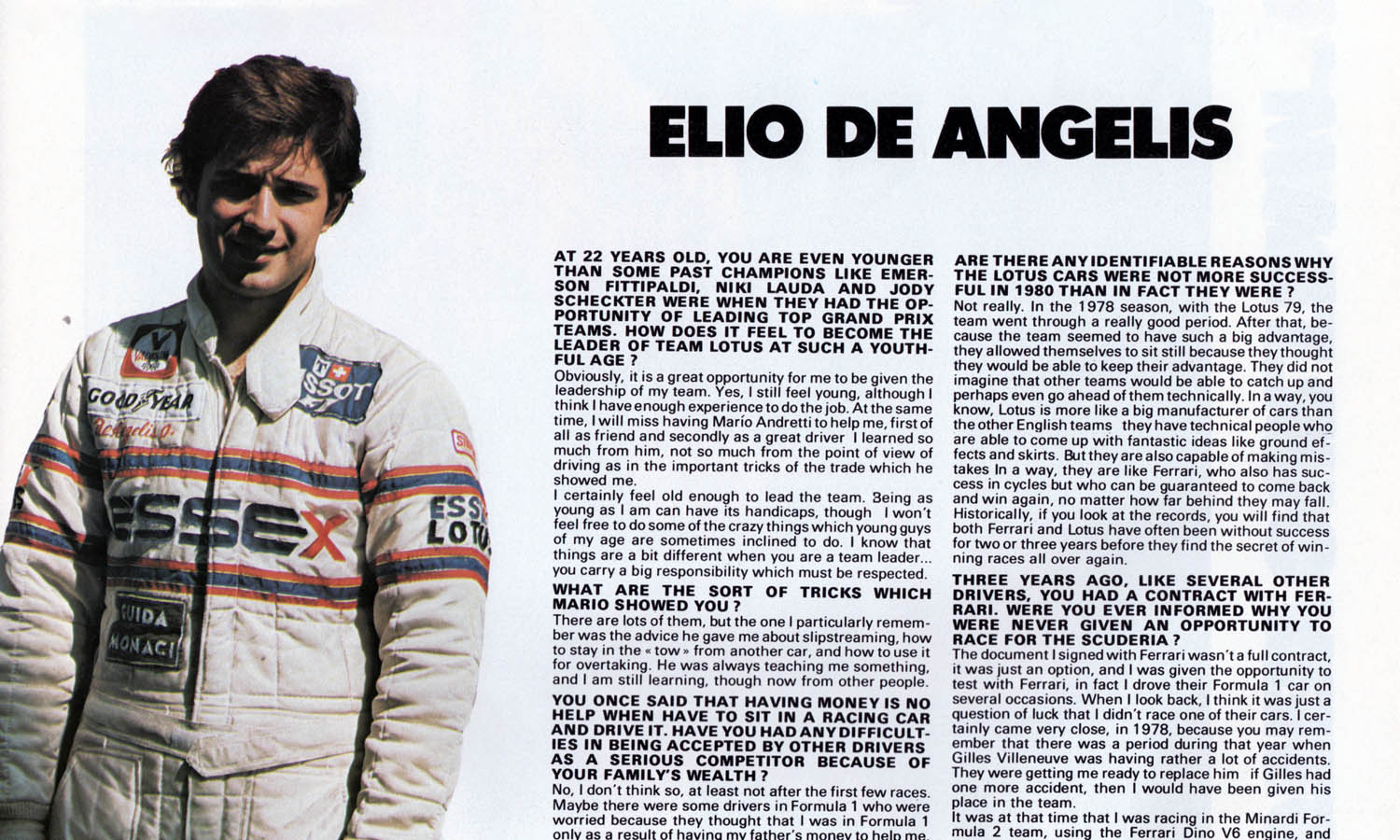

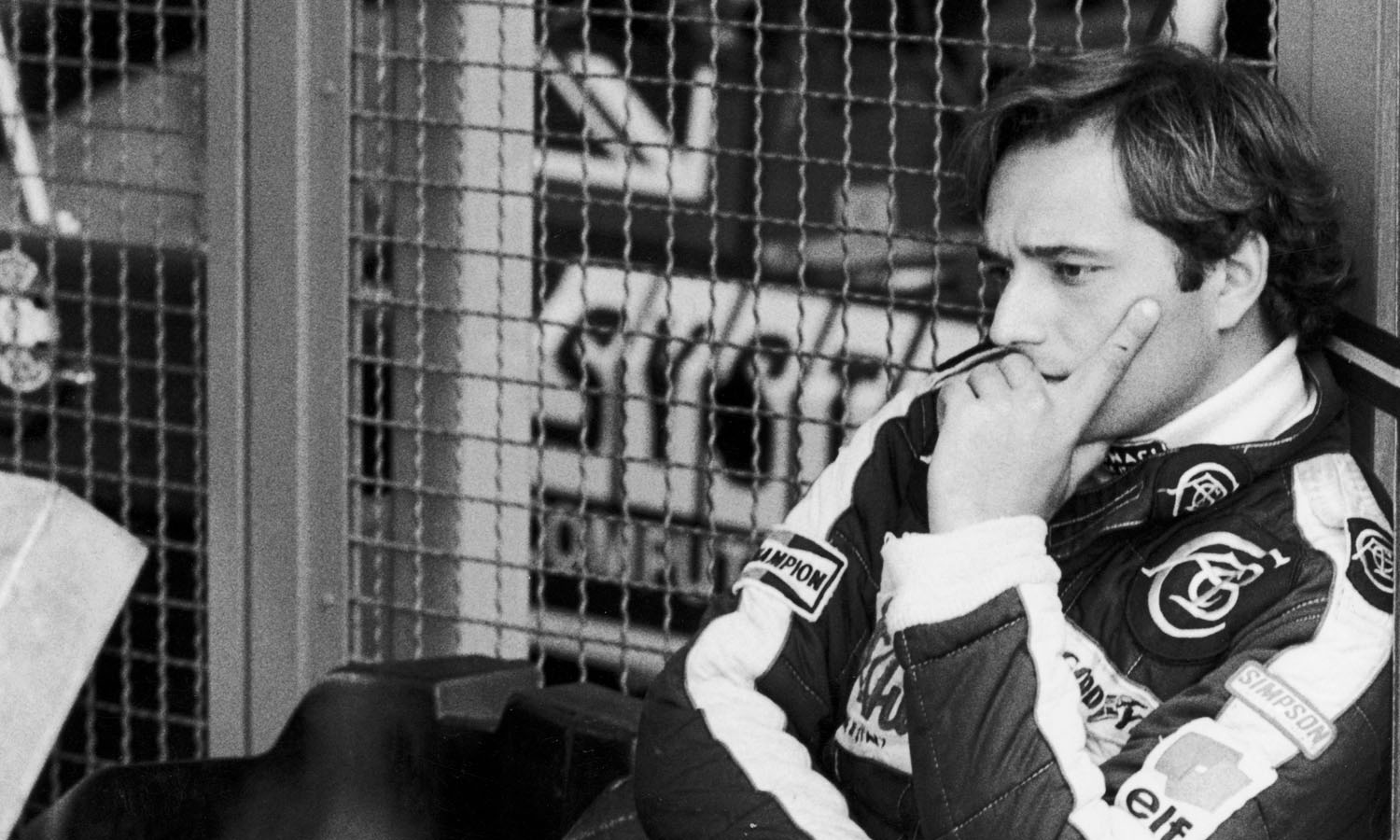

Brought up in a wealthy Roman family, de Angelis first arrived on the F1 scene in 1979 with the Shadow team, shortly before his 21st birthday. He had won the previous year’s Monaco F3 event – an achievement regarded at the time as a passport to the top.

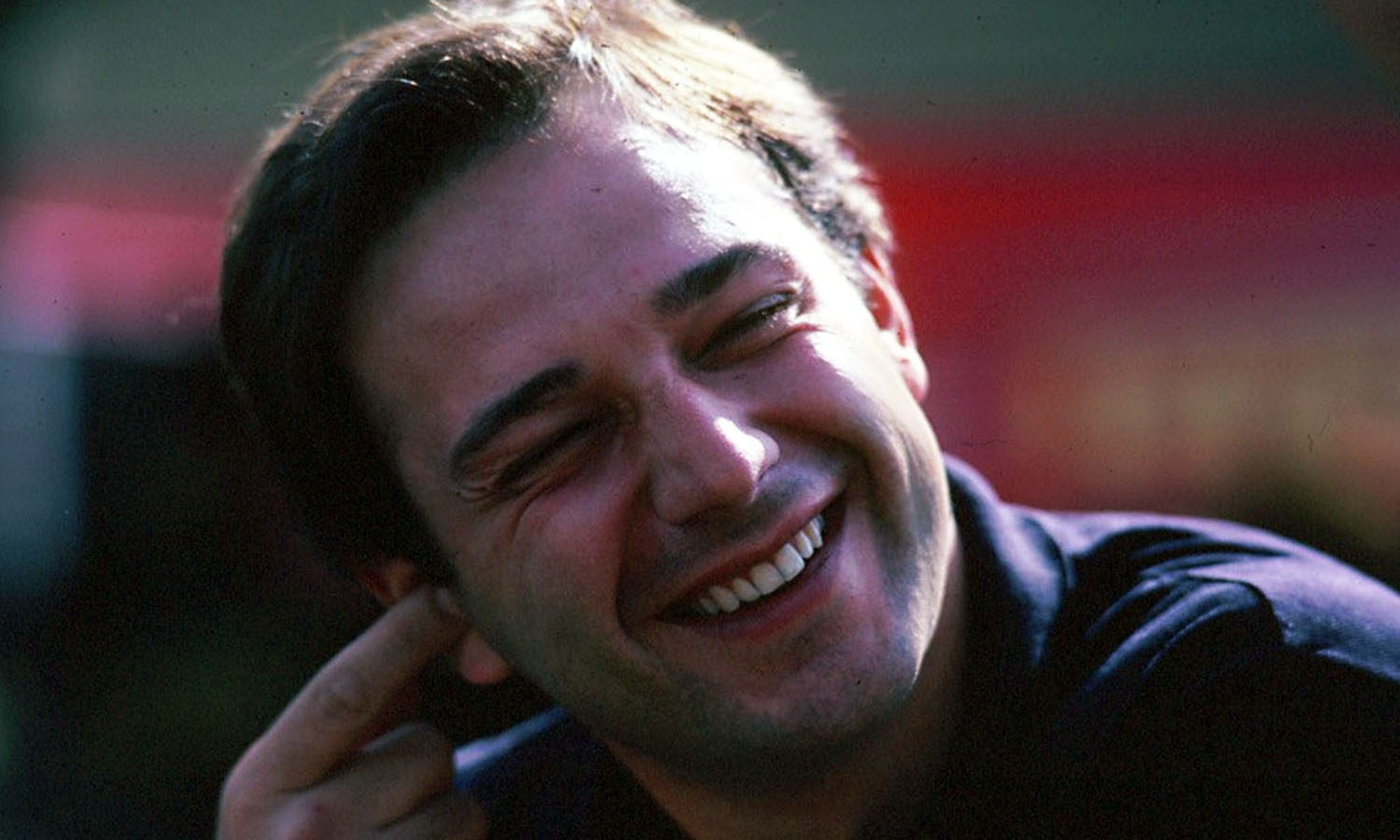

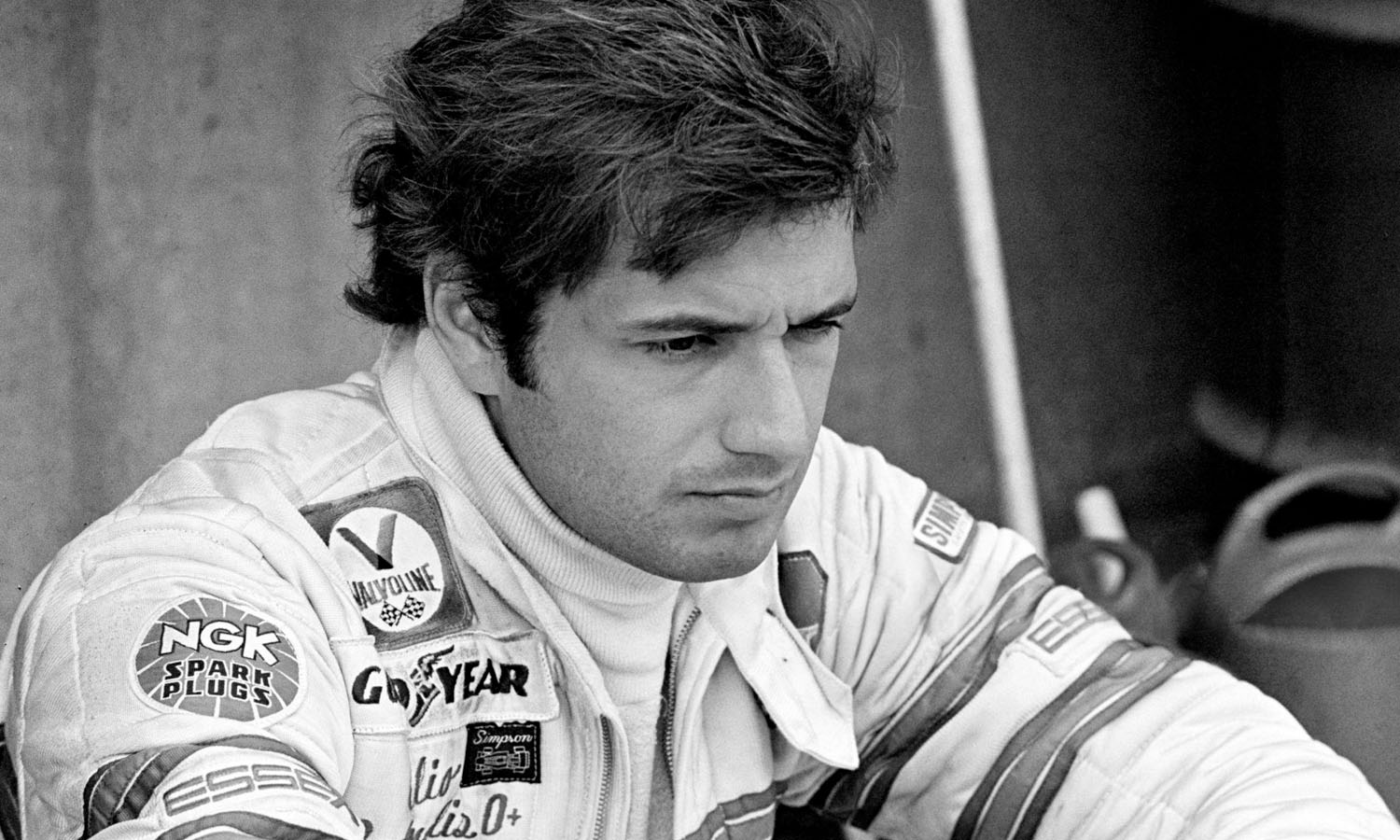

“He was a lovely guy,” says his Shadow teammate Jan Lammers. “I considered him a gentleman, one of the nicest people in F1. He had an incredible amount of class.”

De Angelis concluded his ’79 rookie season with a superb drive to fourth in a wet US GP at Watkins Glen. He then joined Lotus for 1980, and impressed with runner-up spot on only his second race with the team in Brazil. He was to learn much as Mario Andretti’s understudy.

Forever fighting his image as a rich kid, he soon began to establish a reputation as a quick driver. There were moments of petulance in the early days, but he also won people over with his easygoing charm. He had interests outside racing, and in the evenings he enjoyed a cigarette and a glass of whisky.

“He was an extremely talented driver,” says former Lotus team manager Peter Collins. “Beautiful style and technique, very safe, and very quick.”

“Of all the drivers I worked with he was probably the one I liked the most,” recalls Lotus engineer Peter Wright.

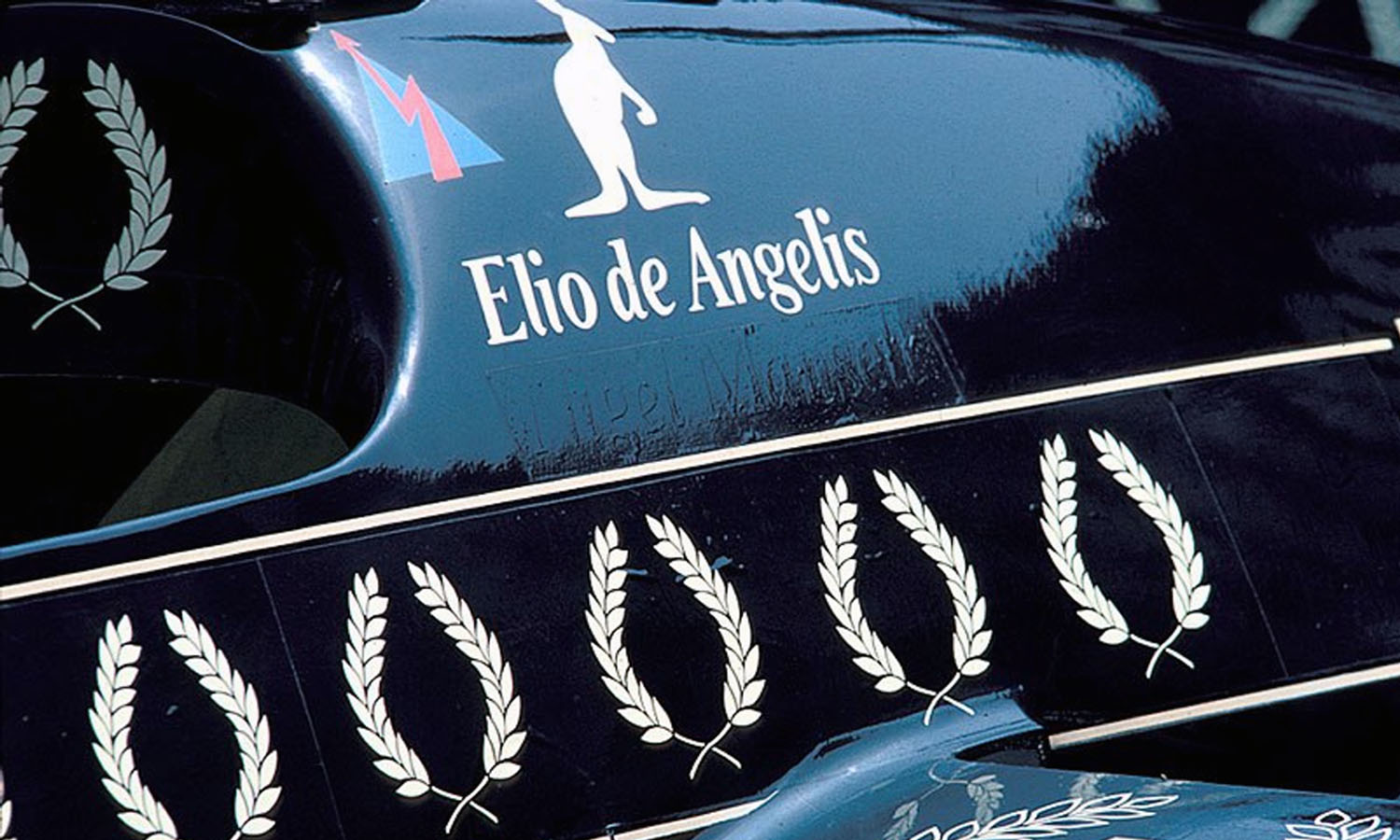

In four years at the team alongside Nigel Mansell de Angelis frequently overshadowed the Briton, taking his first victory in Austria in 1982 when he beat Keke Rosberg by a few metres.

Famously earlier that year he’d entertained his peers with his piano playing during the Kyalami drivers’ strike.

In 1983 de Angelis took his first pole for the European GP at Brands Hatch, although it was a largely disappointing year with the unreliable new Lotus-Renault combination.

The 1984 season proved to be much better. He took another pole in Brazil and with regular top six finishes he earned third in the World Championship, behind only McLaren drivers Niki Lauda and Alain Prost. He logged four podiums, and comfortable outscored Mansell. Within the Lotus camp he was regarded as team leader.

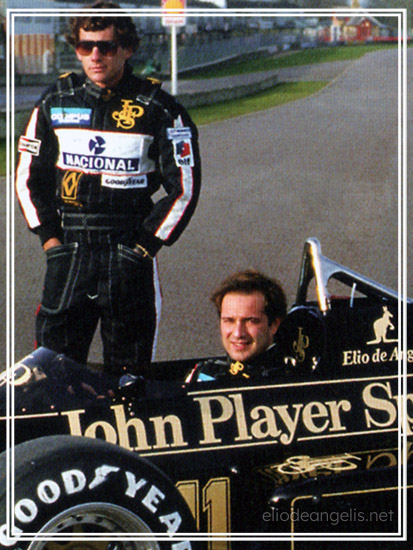

The challenge of Ayrton Senna

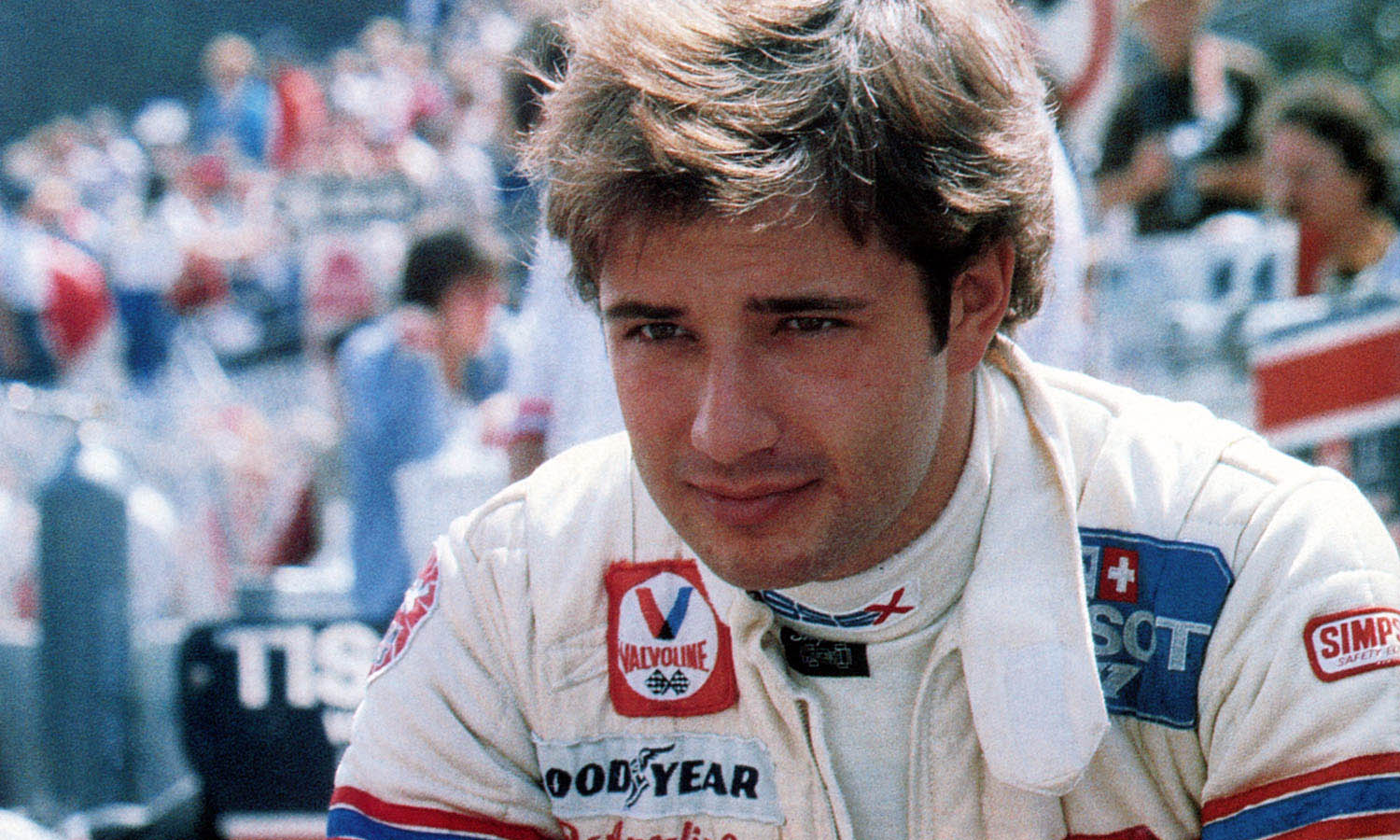

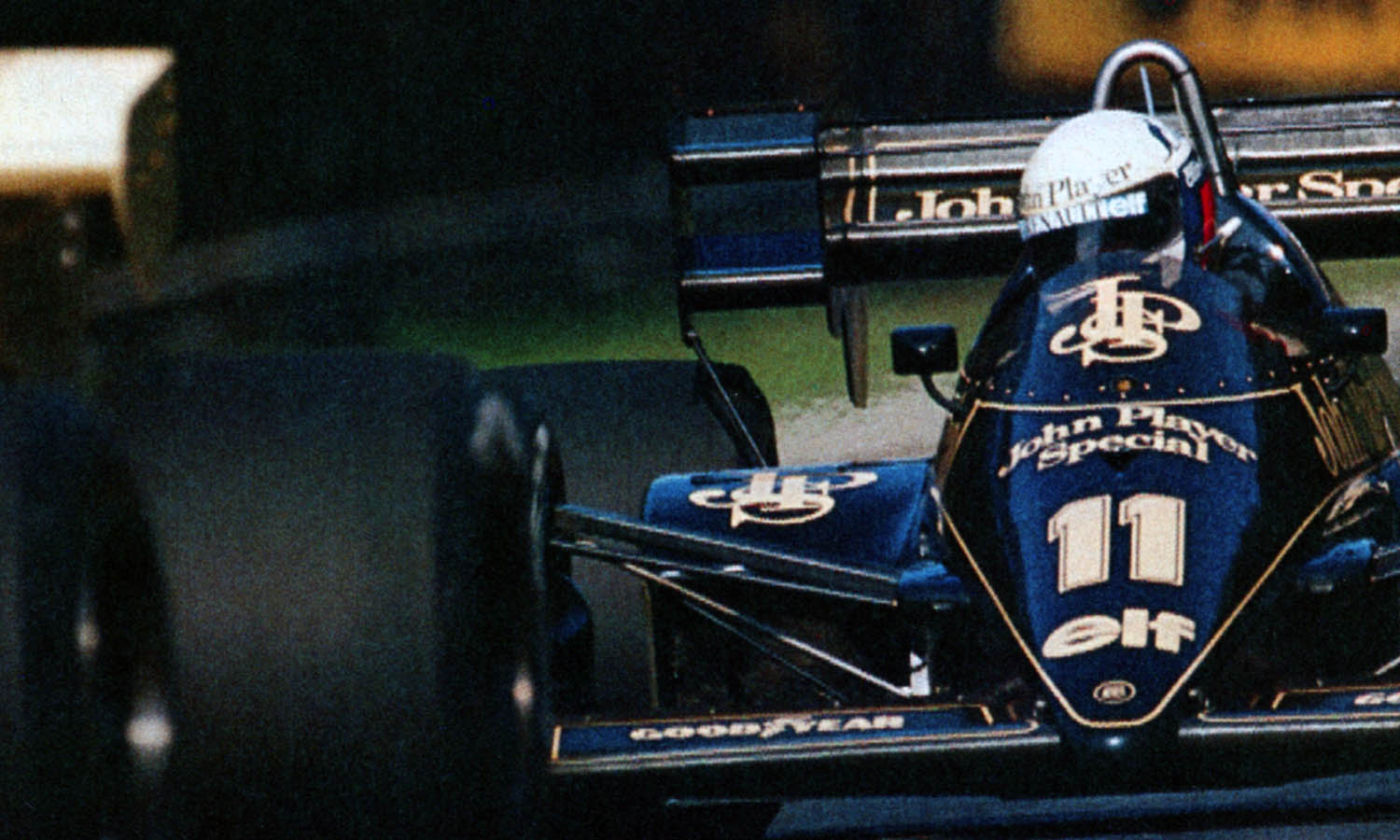

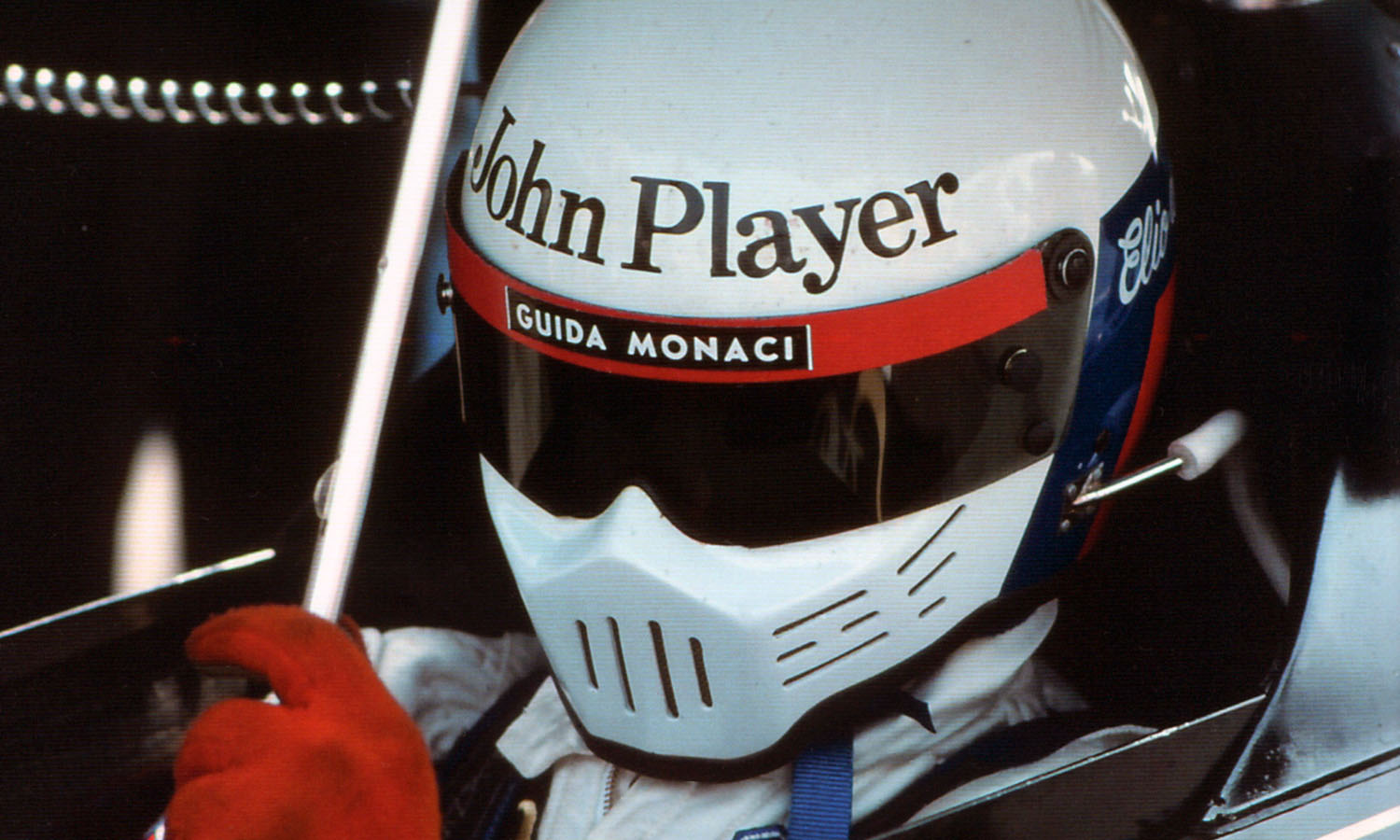

For the 1985 season Mansell was gone, and de Angelis had a new teammate in the form of Ayrton Senna. Inevitably he often struggled to match the mercurial Brazilian’s one-lap pace – although he secured a third career pole in Canada, and qualified ahead of the other Lotus at two other races.

He also earned his second Grand Prix win at Imola after Prost was excluded because his McLaren was underweight. Consistent scoring helped him to fifth in the championship, only five points behind Senna.

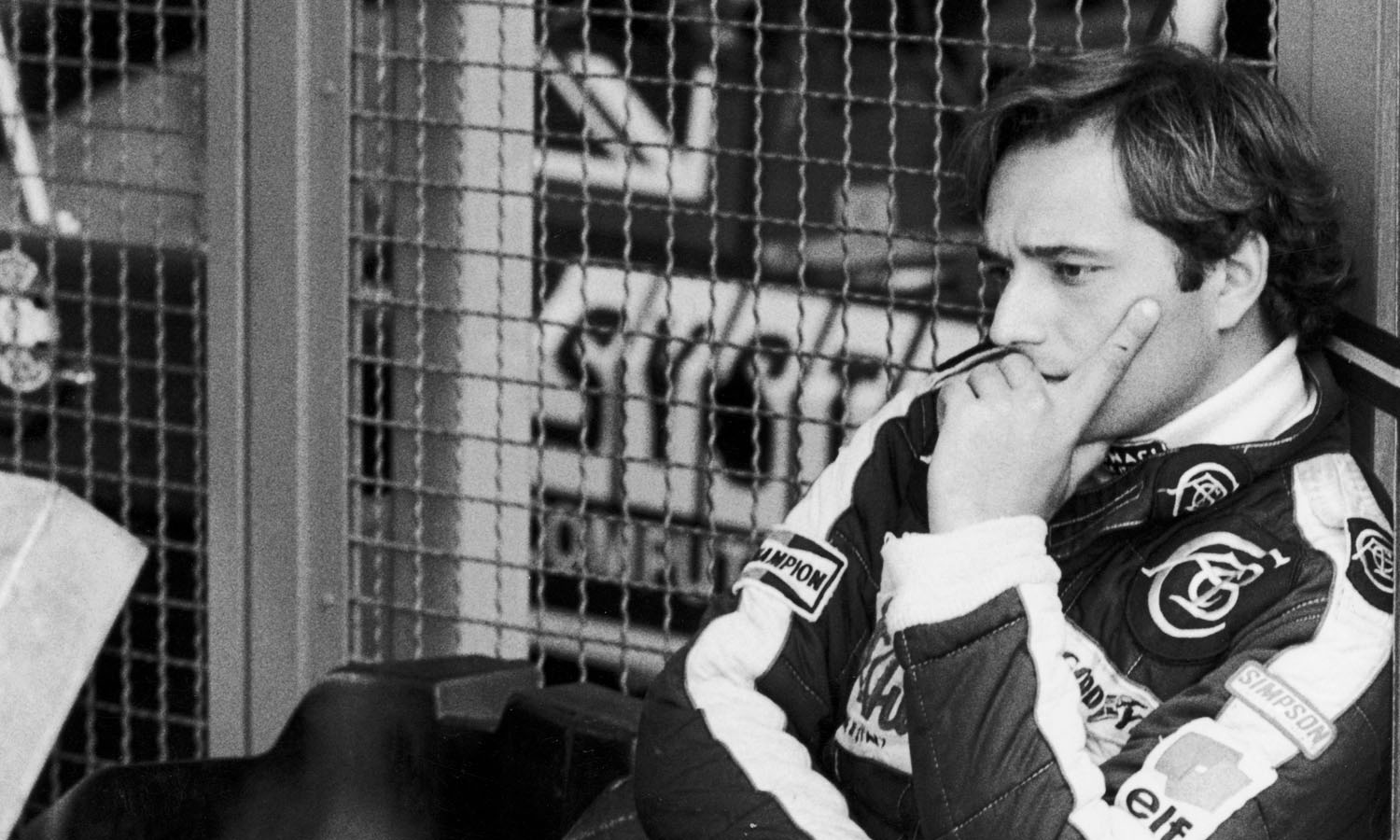

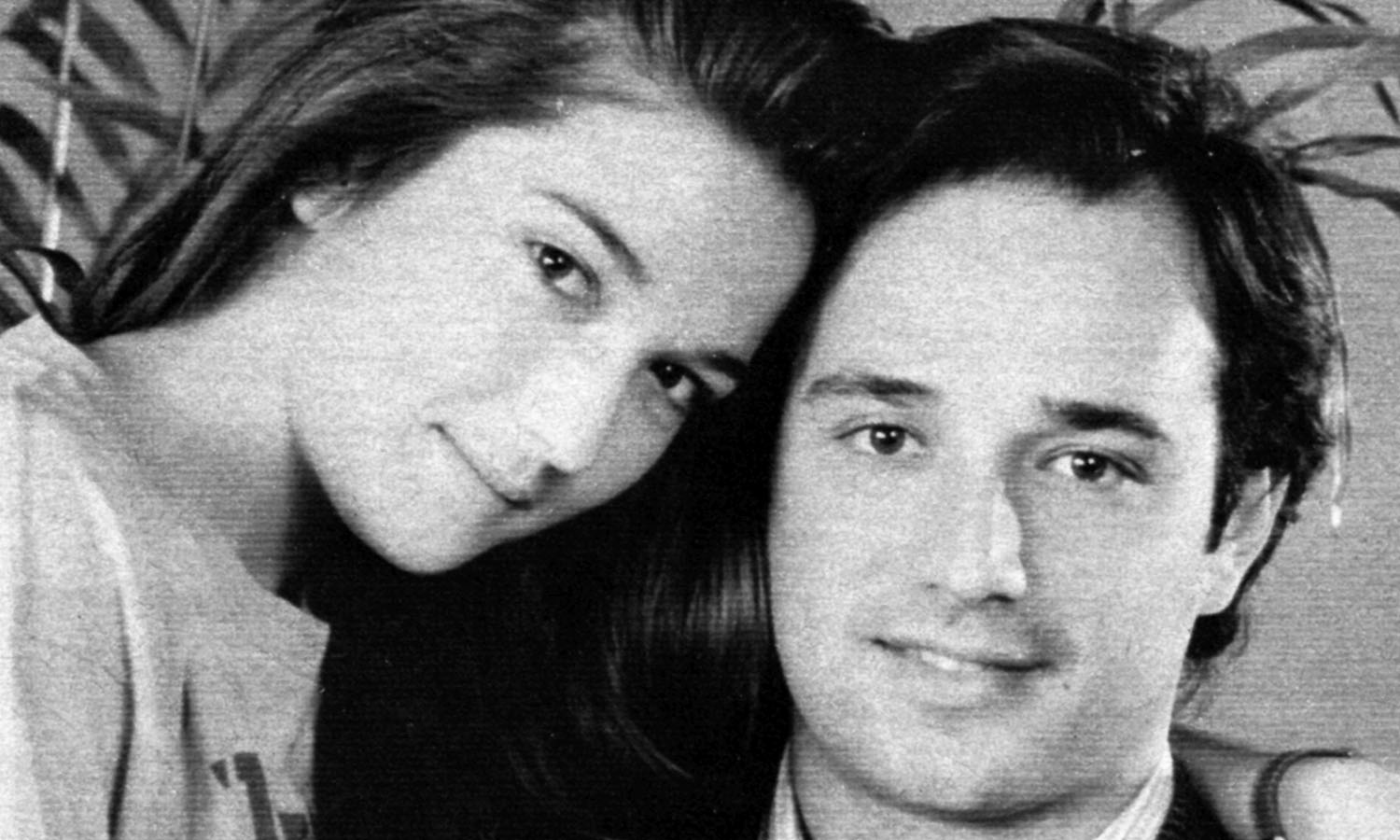

Approaching 28 and with seven years of F1 experience behind him de Angelis was by now established as one of the leading drivers of the era, someone who could be relied on to bring home points, and who on his day could fight with the best.

In 90 starts with Lotus he had finished in the top six on an impressive 42 occasions – and this at a time when reliability was poor, especially in the turbo days.

However, he felt that the Hethel team had switched most of its attention to his teammate.

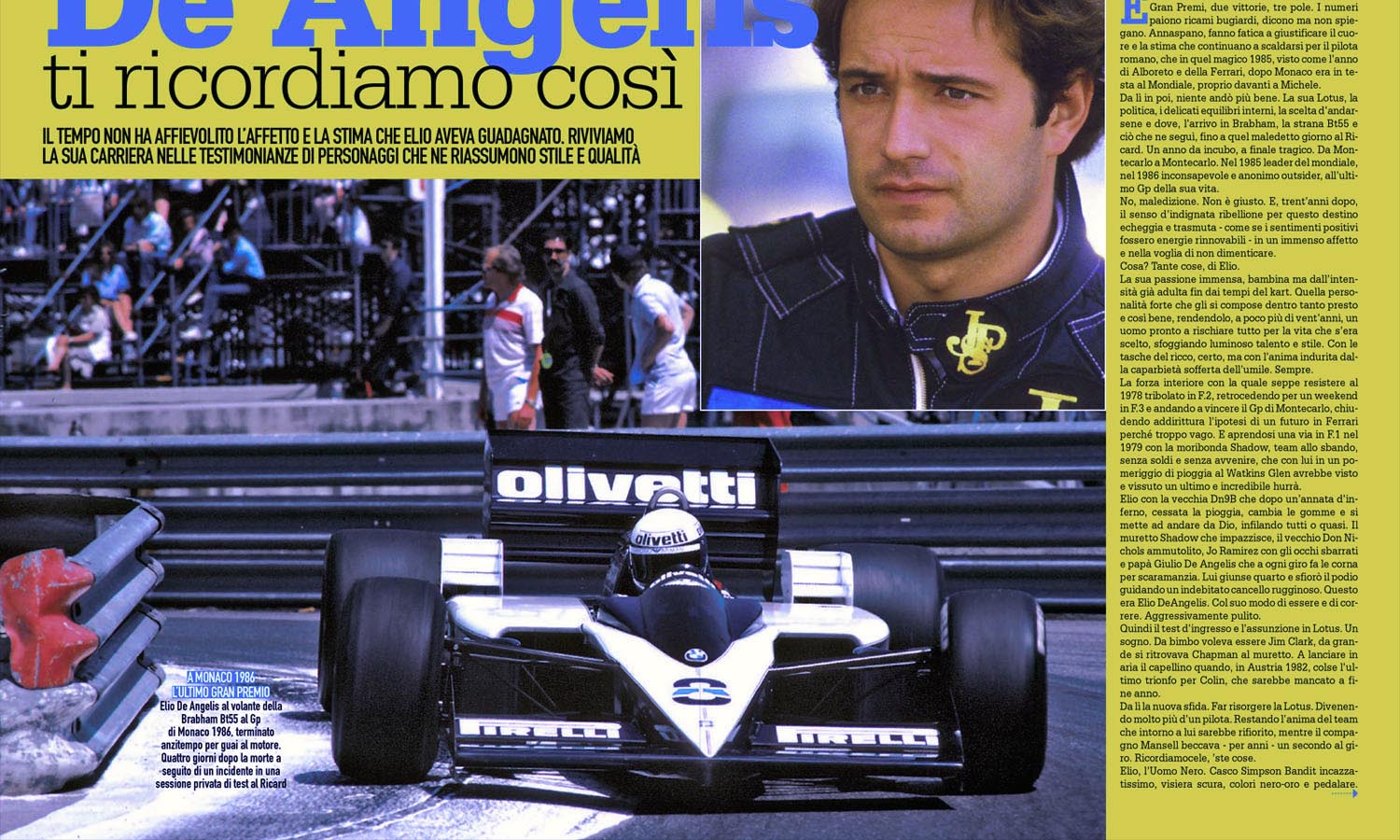

It was time to move on, so he signed to replace Nelson Piquet at Bernie Ecclestone’s Brabham team for 1986, joining his countryman Riccardo Patrese.

A fresh start at Brabham

The late Charlie Whiting, who had moved from his longtime Brabham chief mechanic role to become Patrese’s race engineer, recalled that the newcomer fitted in well.

“He hadn’t been there long, but Elio was very much liked in the team,” Whiting told me in 2014. “He was a lovely guy, and got on well with everybody. He was always a pleasure to talk to, and was generally a very nice chap. But the BT55 was a huge disappointment.”

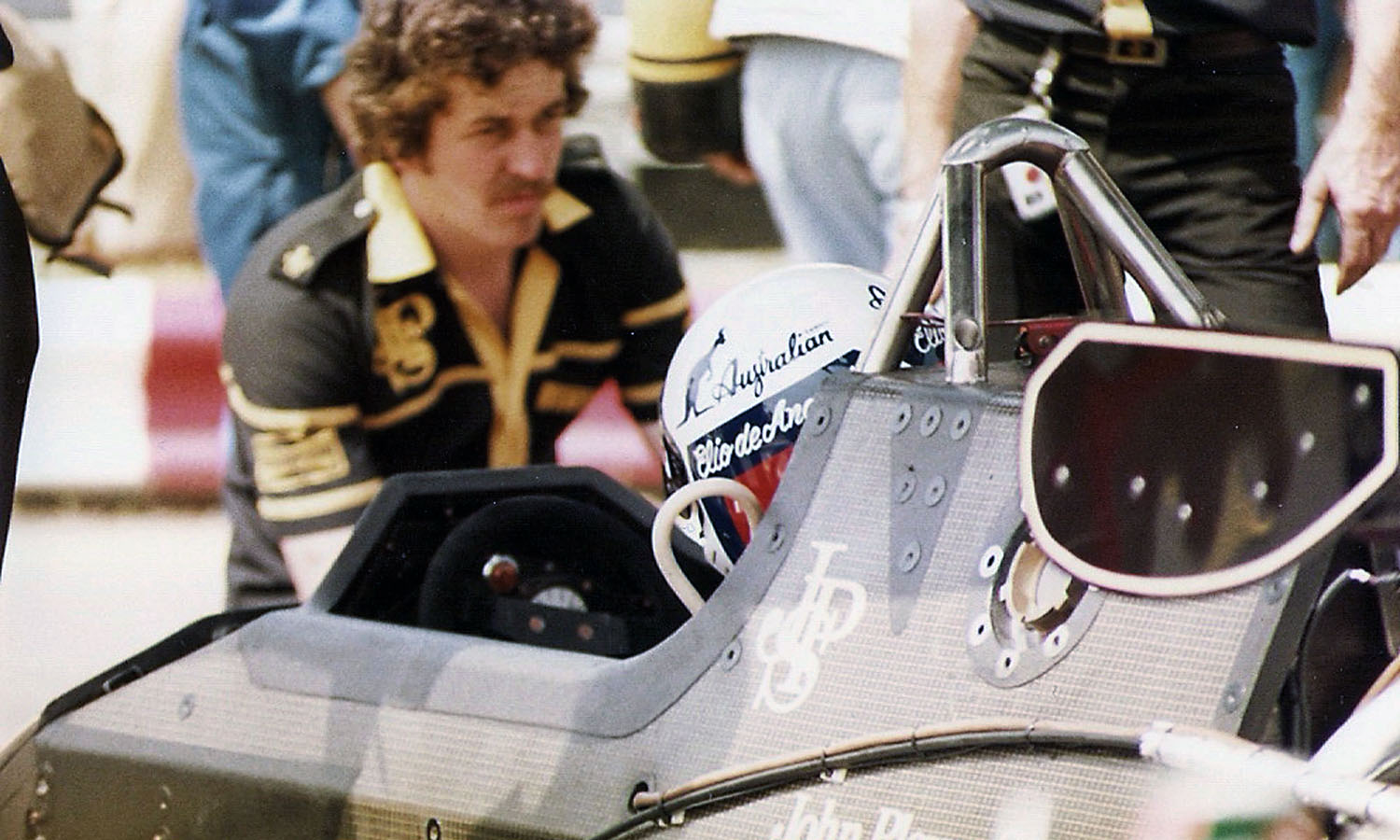

Gordon Murray’s new car, with its distinctive low-line look and awkward cockpit position, promised much – but the reality proved to be disappointing.

“It should have been brilliant,” former Brabham team manager Herbie Blash recalls today.

“I do remember sitting in the pub with Bernie, Gordon, Elio and Riccardo. We were going to toss a coin as to who was going to win the first race, we were that confident. We were just going to walk it with this one…”

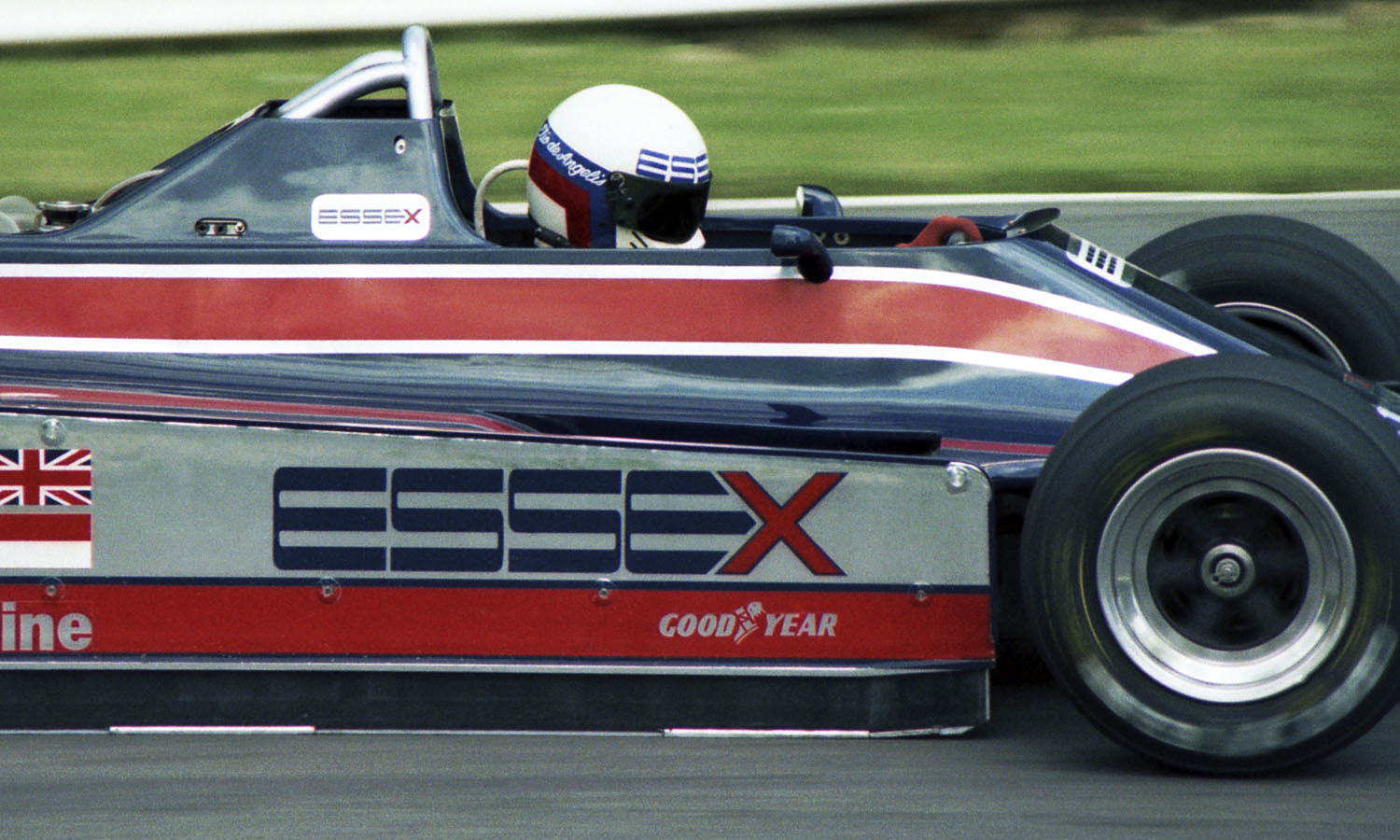

Even Brabham veteran Patrese couldn’t do much with the difficult car, and after finishing eighth in Brazil de Angelis suffered three successive mechanical retirements.

In the previous two seasons he’d started in the top 10 at nearly every race – his best grid position in those four Brabham outings was 14th.

After a frustrating weekend in Monaco the team went straight to the official pre-French GP test at Paul Ricard. Only recently had the race been switched from its originally scheduled venue at Dijon.

May 14th 1986 – a needless waste

On the second morning de Angelis was the only driver on the track when he suffered a rear wing failure at the high speed S-bend after the pit straight – later a detached endplate was found on the track at the point where he first lost control.

“It was the almost flat, but not quite flat, series of kinks after the pits,” Gordon Murray told me 10 years after that bleak day. “We had a huge off before there with Francois Hesnault. And Elio had exactly the same shunt at exactly the same place.”

This being a test day, nobody witnessed the whole incident, although two Benetton mechanics manning a speed trap caught the final stages.

The car became airborne and then flipped into a series of rolls that pitched it over the guardrail, before it eventually came to rest inverted. The survival cell was intact, but the rollhoop atop the fuel tank had been damaged as the car bounced over the barrier, and fuel was leaking out. De Angelis himself had suffered only a broken collarbone.

Whiting, who didn’t attend the test, recounted the story: “Despite the high-speed nature of the accident, and its severity – he went end over end and over the barrier and landed upside down – he was almost uninjured.

“Fuel tanks and breather systems and those sorts of things weren’t nearly as good as they are these days. Fuel got out and presumably ignited on some of the very many hot bits that there were on turbo engines in those days.

“There were only four gallons of fuel in the car, which by some standards was very little. You know what sort of fire you can get with even just that amount of fuel.”

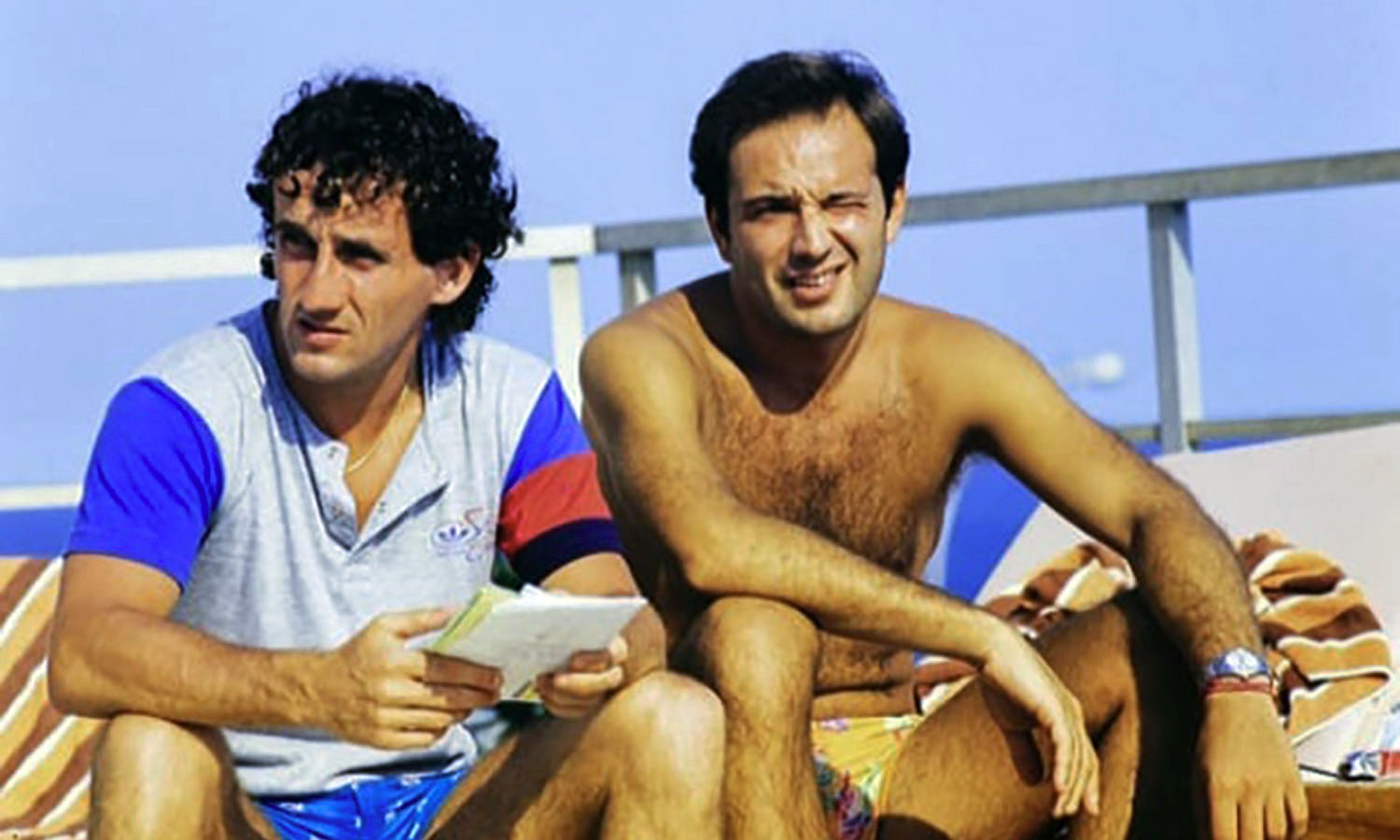

Alan Jones, on his way out of the pitlane to start a run, was the first driver on the scene, and he immediately parked and ran across. Alain Prost, who was following the Beatrice Haas, also stopped.

Initially there was only some smoke. With little official help – Jones said later that he was joined by two marshals wearing shorts “who just didn’t have a clue” – attempts to turn the car over proved fruitless.

Gradually a fire took hold. Meanwhile crew members from Brabham and other teams began to arrive from the pits. It was all too apparent that, this being a test day, there was insufficient safety cover – there was no Prof Sid Watkins, no fire vehicle and, it soon emerged, no helicopter.

“My guys shot down in a hire car,” Murray recalled. “The main problem was not being able to turn it over. Because he was not badly injured he could have been pulled out pretty quickly, had the fire been kept down a bit.

“I arrived much later than the mechanics., and we couldn’t get near the car because of the fire. When the fire truck did eventually arrive, which was miles too late, the hose blew off. It was pretty needless, that’s the terrible thing.”

There was a lot of confusion at the scene, and reports suggest that some of those present believed that de Angelis was already beyond saving, and that there was nothing they could do.

Drivers began to walk away, leaving guys in shirtsleeves to try to right the car. The fire kept flaring up, fed by the leaking fuel.

When recalling that day some years later Tyler Alexander, then part of the Beatrice team’s management, made clear his feeling of helplessness.

“There was a big pall of black smoke,” he told me. “Nobody seemed to be doing anything, so we grabbed a couple of extinguishers in the pits, and drove down there.

“A couple of drivers were walking back. They had walked away, because it was quite a big fire. But the fire was in the back of the car. “Robin Day [of Brabham], John Barnard and I tipped the car back over.

I almost got poked in the eye with a bit of the suspension, I got a black eye, and we were all covered with that goddamn powder. And Elio was just sitting in the car.”

“I just remember standing there watching the car go up in flames,” former McLaren designer Barnard recalls today. “I did help to turn the car over after the fire was out, but there still wasn’t anyone there to help Elio, like a doctor or medic of any sort.

“Once we got the car to tipping point it went down with a bang, which wouldn’t have done poor Elio’s neck much good.

“When I think back to those days and ponder on how little safety requirement there was for testing I wonder we didn’t have more horrors like that day. There is nothing I can add except that it was the worst scene I have ever witnessed. I’ve tried to block it out.”

Video footage shows some very brave men in normal clothing standing close to and even on the Brabham, despite the very obvious risk that the fire could take hold once more.

Eventually de Angelis was removed from the car. He’d been starved of oxygen by the flames, and it was discovered that he had no heartbeat.

“We took his helmet off, and we really weren’t sure of his condition,” said Alexander. “Here was this guy with absolutely nothing wrong with him as far as we could see – there was no blood, nothing.

“There was a young medical guy there with us, who didn’t speak English, and in the end he got out a big syringe and stuck it in his chest.

“Eventually a helicopter came, with some paramedics. They checked his pulse and stuff, and the line was moving. We carried the stretcher over to the helicopter.”

Having been resuscitated, de Angelis was transferred to the same hospital and seen by the same doctors who had treated Frank Williams after his road accident just a few months earlier. Brabham team manager Blash was back at base in Chessington, but he soon received a call from his crew. He hurriedly booked a flight and flew straight to Marseilles.

“I was going through the airport and the first person I saw was Nigel Mansell,” he recalls. “He looked at me, tears were in his eyes, and he just said to me, ‘It’s bad.’ I jumped in a hire car went over to Ricard. Then I stayed at the hospital until the end.”

The rescue had come too late for de Angelis, and he died the following day in hospital, a victim of asphyxiation.

The lessons learned

Had the car been righted, and the fire put out quickly, there’s little doubt that the outcome could have been different.

In the aftermath of the crash there much talk about safety standards, especially at testing. The lack of an official requirement to always have a helicopter on site suddenly seemed like a tragic oversight.

However as is so often the case, the momentum for change faded over the years. It was only after Imola 1994 and on Max Mosley’s watch that it was rebooted. The FIA developed a laser sharp safety focus, one that continues to this day.

Along with Sid Watkins, Whiting played a key role in that process. He left Brabham for a technical role at the FIA a couple of years after the accident, and while his remit didn’t expand to include safety matters until several years later, he would never forget the circumstances that surrounded the de Angelis accident.

The tragedy was a bitter blow too for Brabham owner Ecclestone, who had previously lost his close friends Stuart Lewis-Evans in 1958, and Jochen Rindt in 1970.

“It wasn’t good obviously,” he recalled. “Elio was a super guy, and he was very quick. Losing people that you are friends with is never nice. I was closer with Jochen than anybody.

Thank God these things don’t happen anymore.”

Indeed the legacy of Elio de Angelis is that the sport became safer.

“These days people get annoyed because the helicopter hasn’t arrived for testing, whatever the reason, and nothing can start without it,” says Barnard. “They need to see what happened that day. Then they wouldn’t get annoyed.”

© 2021 Motorsport • By Adam Cooper • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended