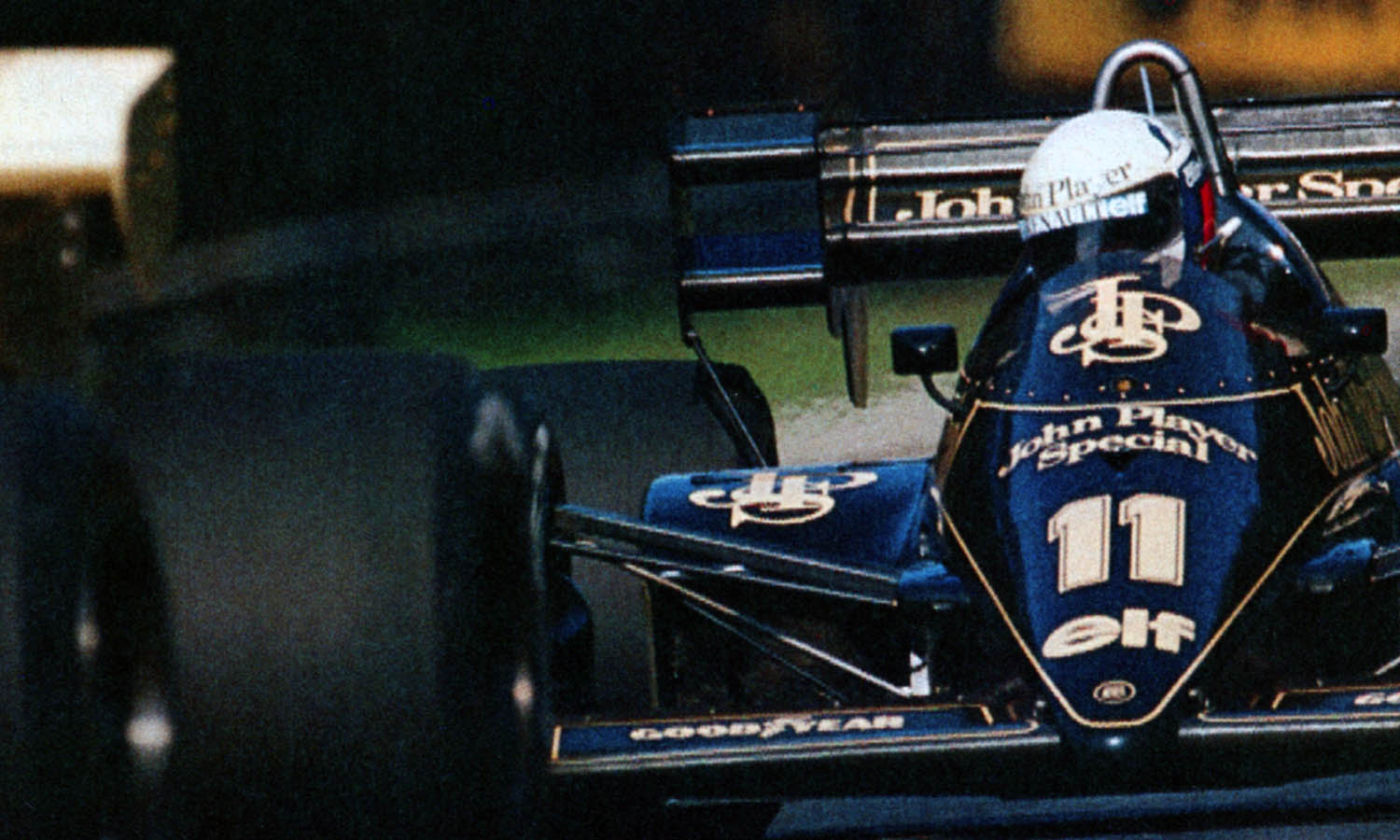

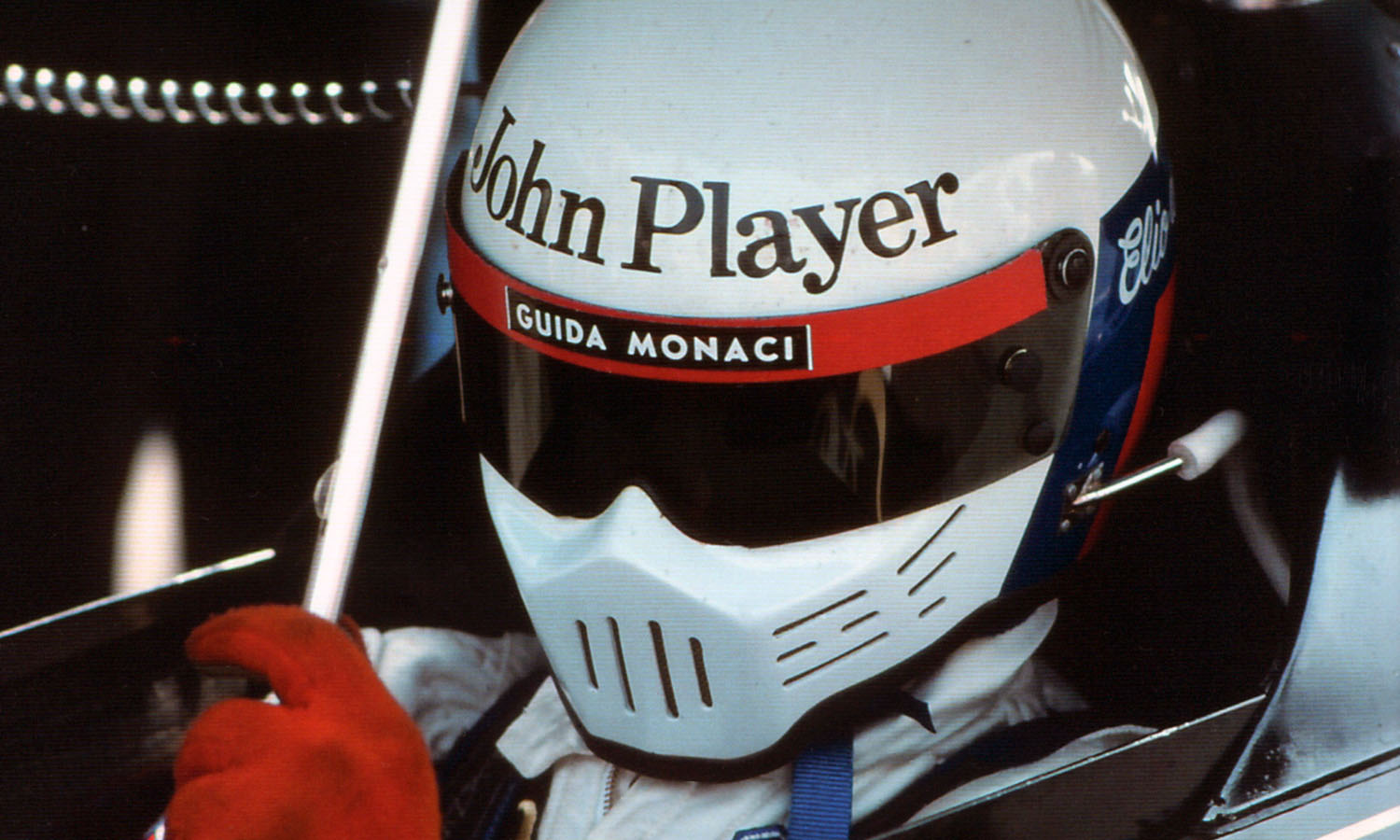

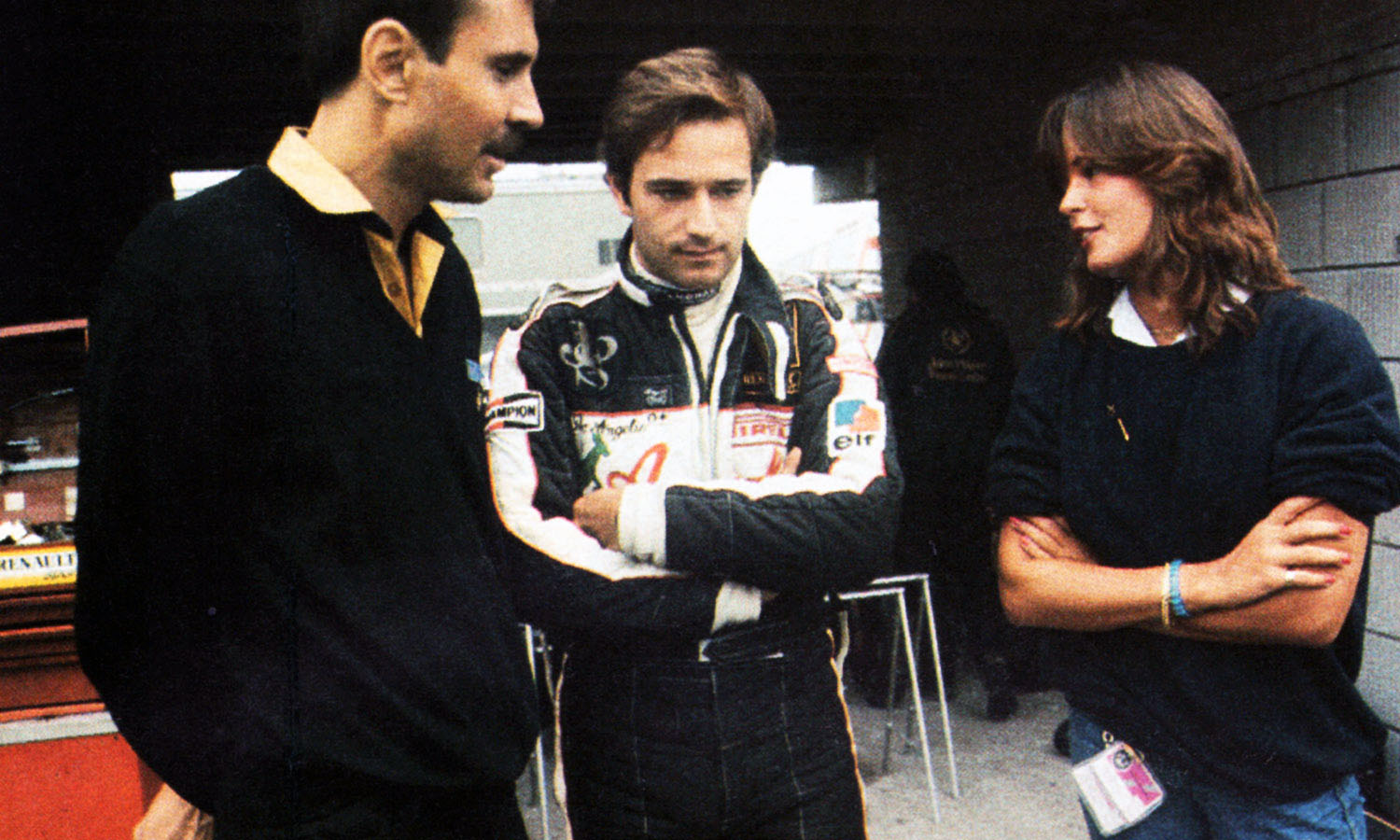

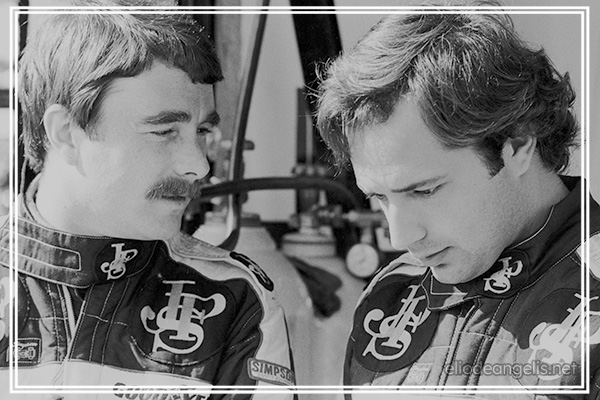

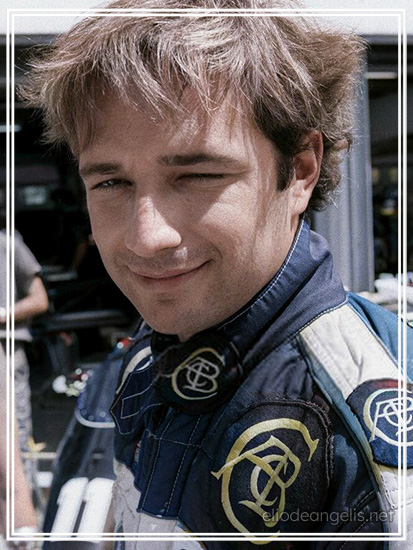

He is the Italian on duty. But with no regrets for lost opportunities at home. He has been able to combine the fruits of experience with his usual intelligence, finally becoming a top-class driver in this F1 world championship. This is so true that at Lotus they are finally forced to "cure" him as much or more than Mansell. He won his race with the British and tells us how.

Translated by this website

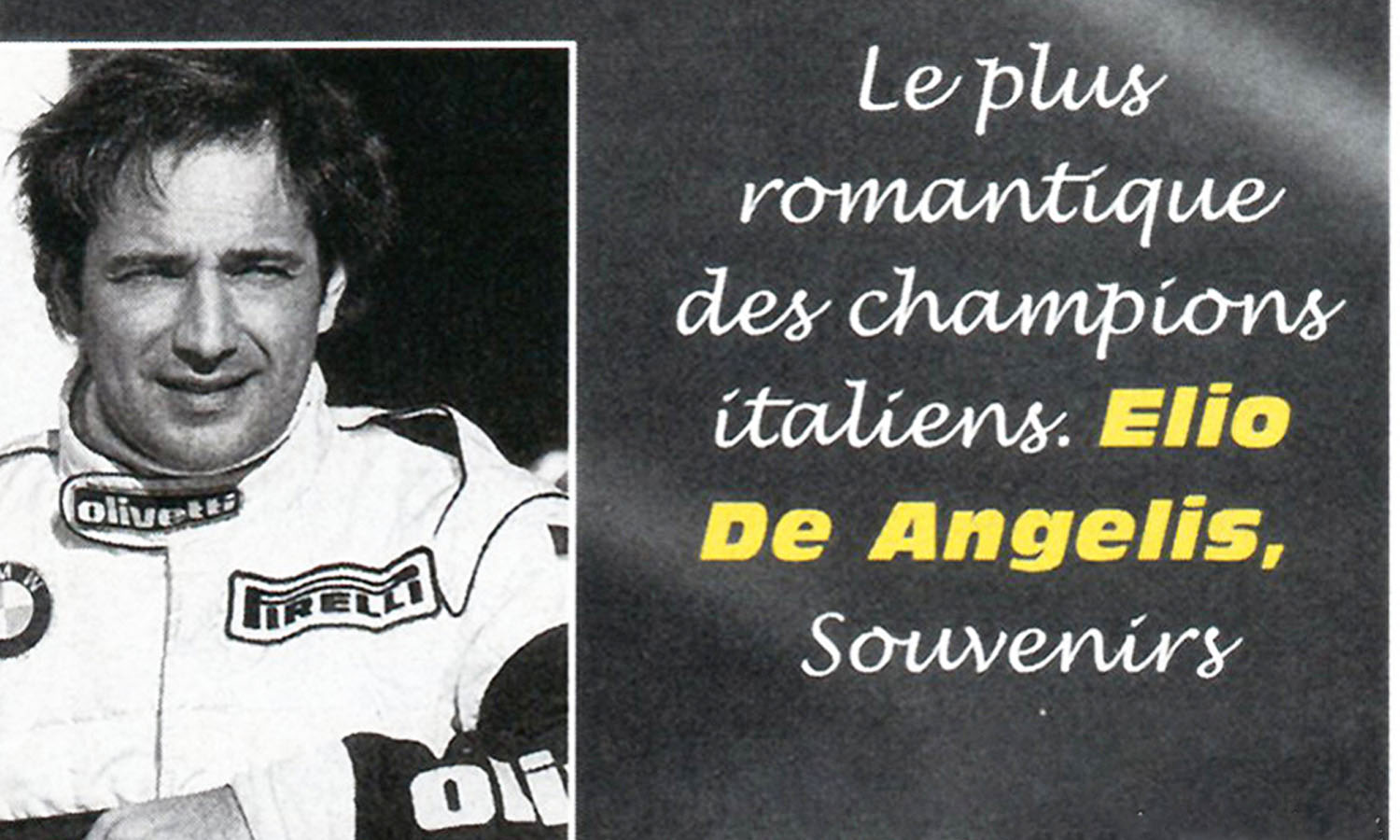

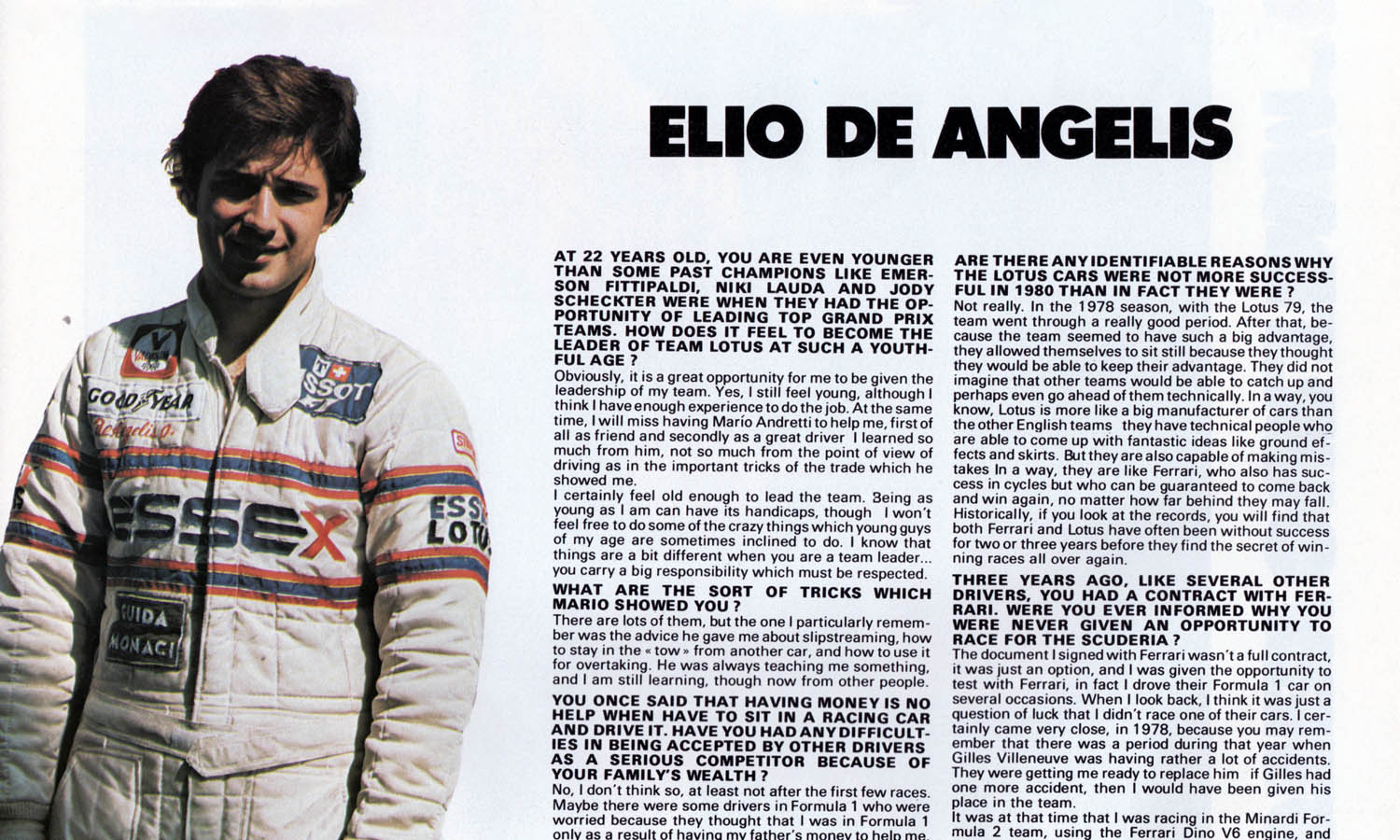

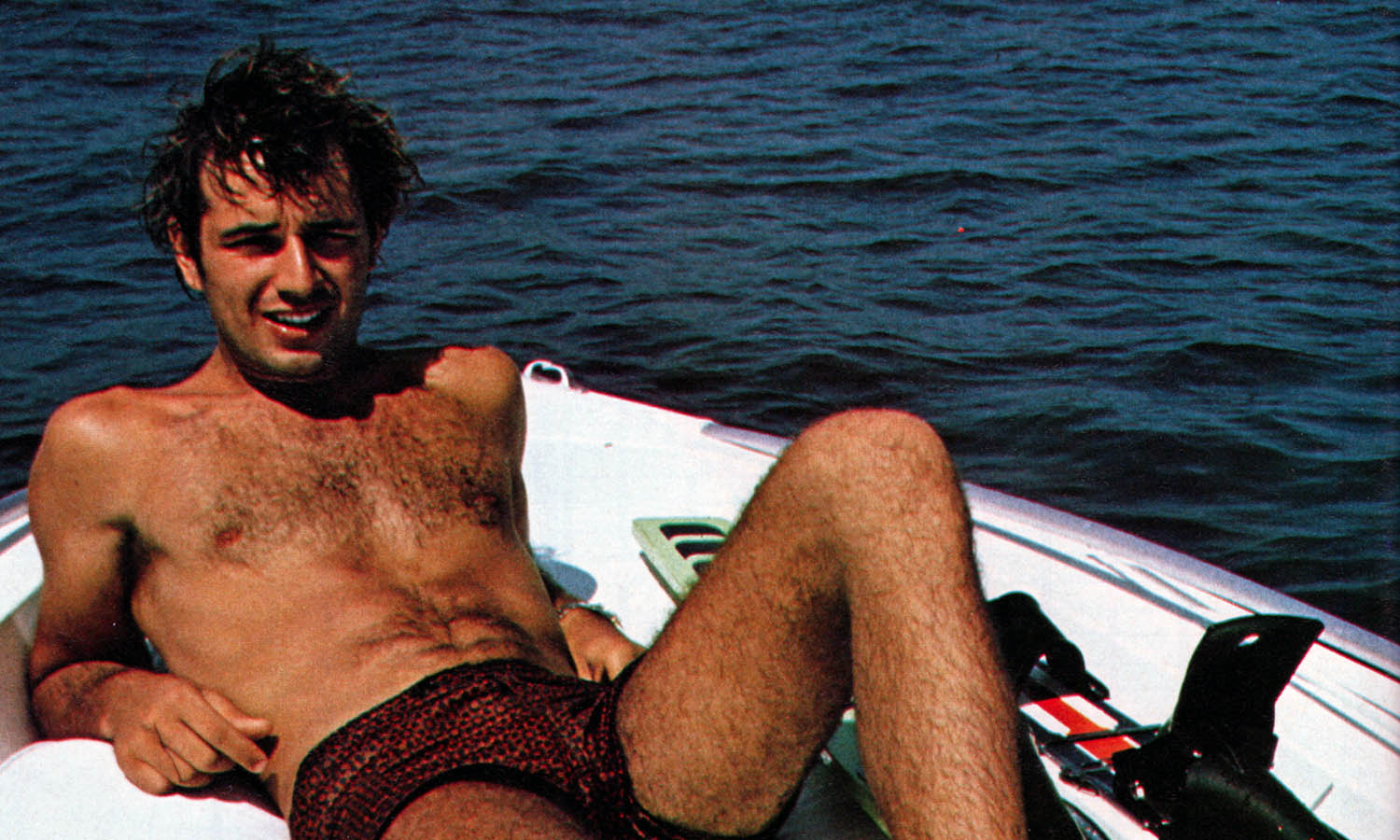

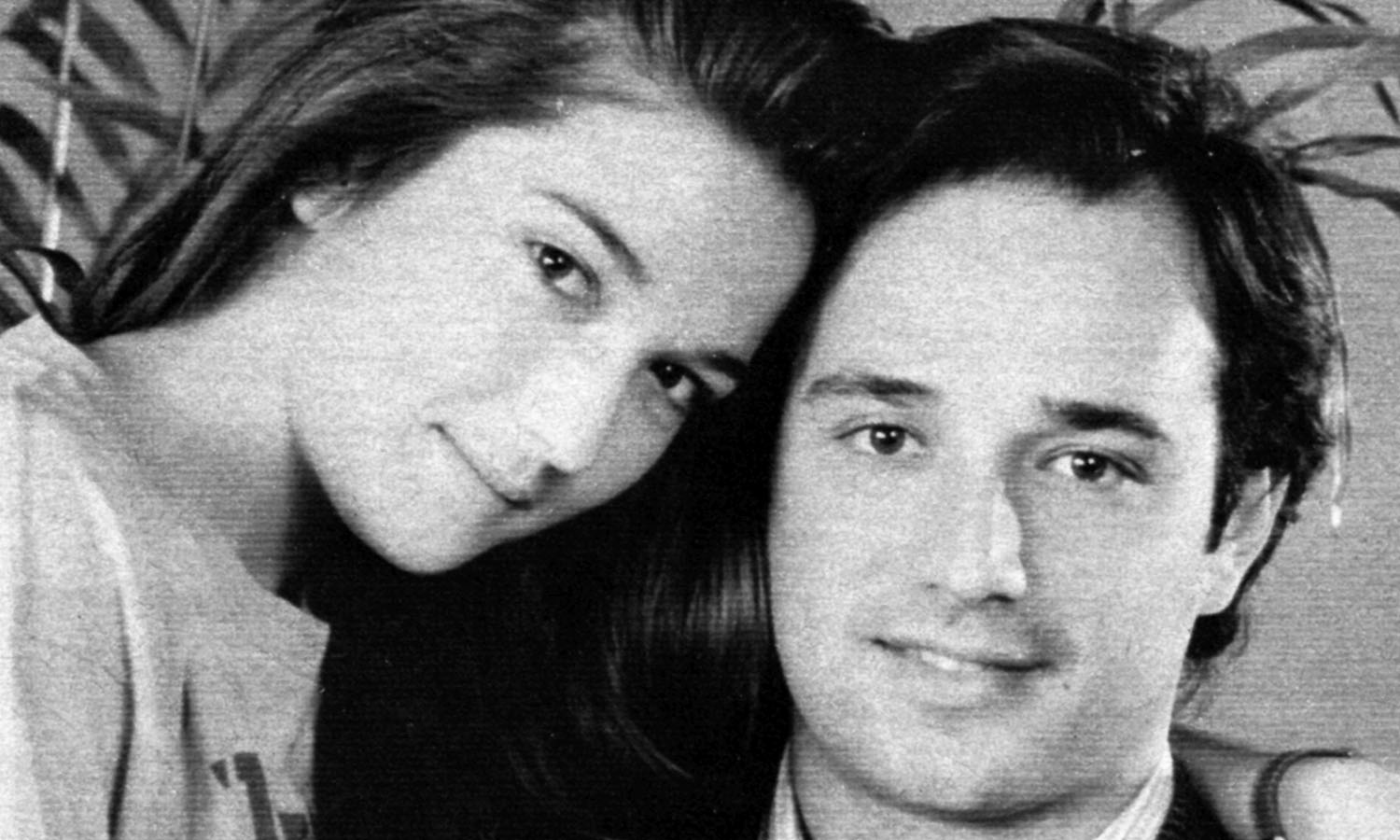

ABOUT THE LIFE of the Roman high bourgeoisie by now everything has been said. If many clichés can be traced back to well-defined stereotypes, it is also true that the existence of many wealthy kids in Rome passes through very specific canons. From adolescence spent in the elegant streets of Parioli and Piazza delle Muse to frequent nightclubs almost by “obligation”, passing through weekends in Fregene and Christmas holidays in Cortina. It is a life that goes smoothly, without problems, but also without particular emotions. And it is perhaps to seek emotions a little stronger than normal that already at the age of thirteen Elio de Angelis was regularly frequenting the golden kart track on the outskirts of Rome.

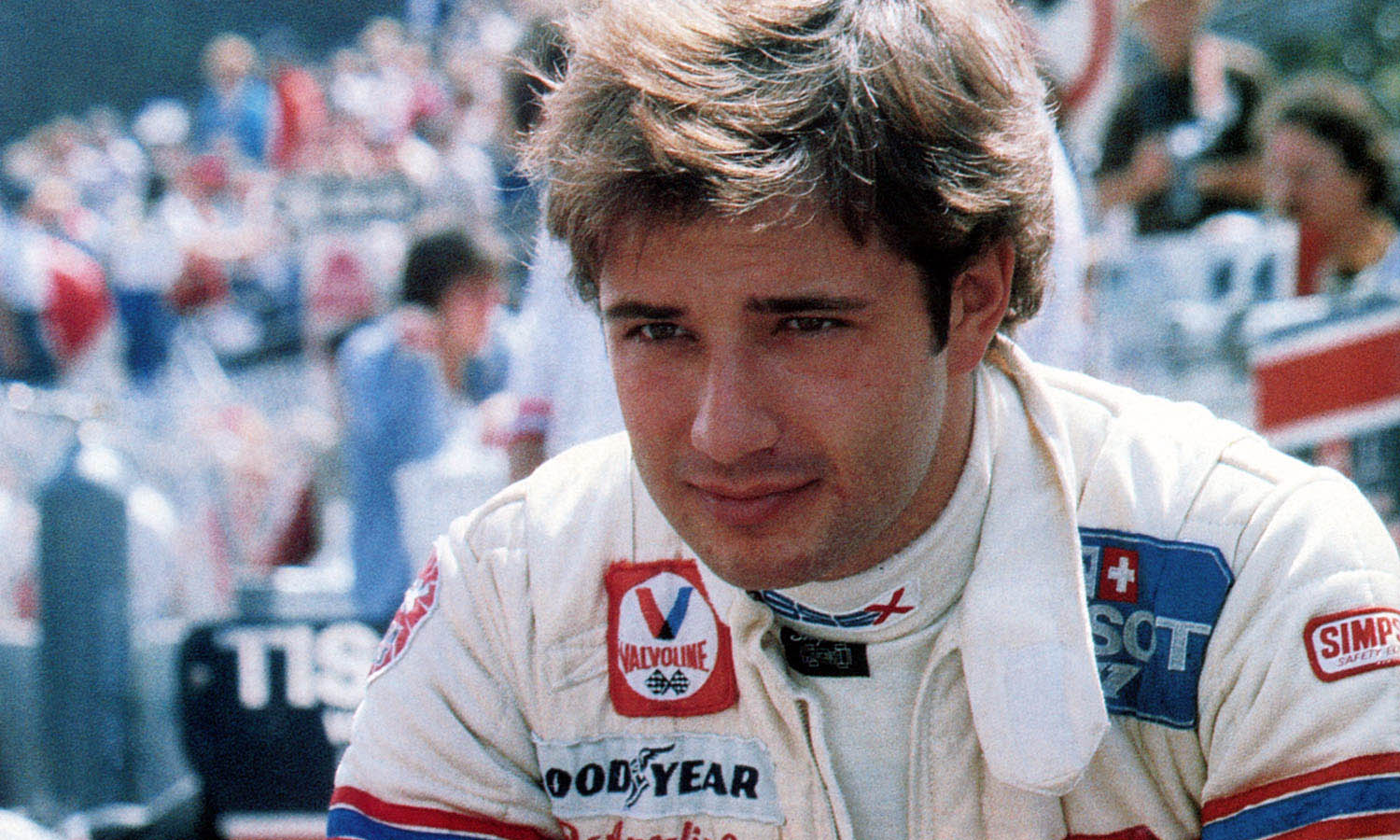

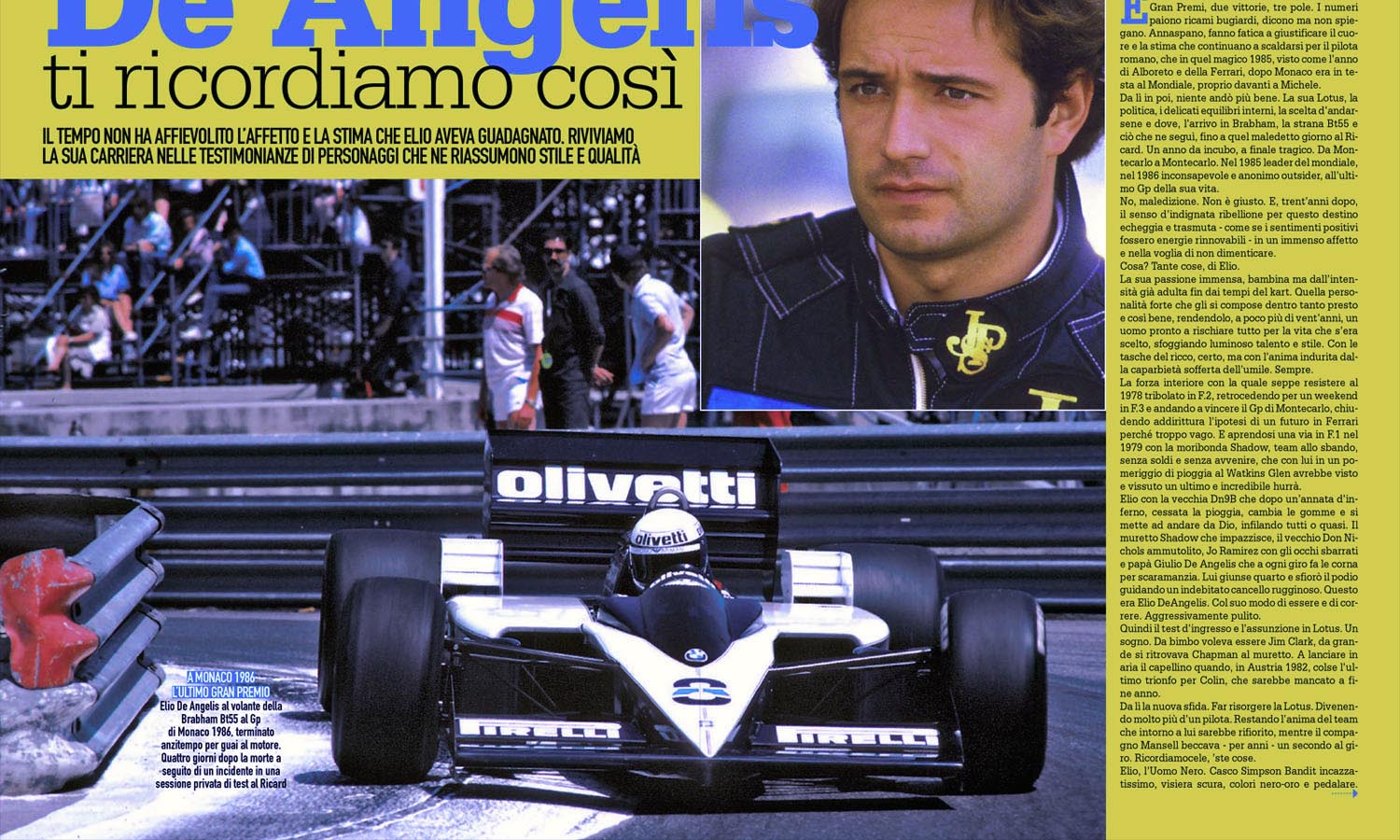

Since those times, Elio de Angelis’ career has developed almost in a frenzy. From the Italian kart team, with breathless duels with Riccardo Patrese, to his beginnings in Formula Three, where, arriving on the circuits with his father’s private plane, he greatly contributed to increasing the fame of “boy with a suitcase”. Like other Italian drivers, De Angelis also went through the great Ferrari illusion: however, for the Roman the parenthesis with the Cavallino was not a missed opportunity or a dream that dissolved in the inconsistency of the F2 Dino engine. For De Angelis, Ferrari meant the possibility of taking his first steps in F1, regardless of any promise to make his debut in racing. Elio has very little left of the Ferrari period, perhaps only the difficult relationship with Gilles Villeneuve, for the rest, the Roman found his consecration in England, experiencing first hand the troubled moment of the Lotus, culminating in the death of Chapman.

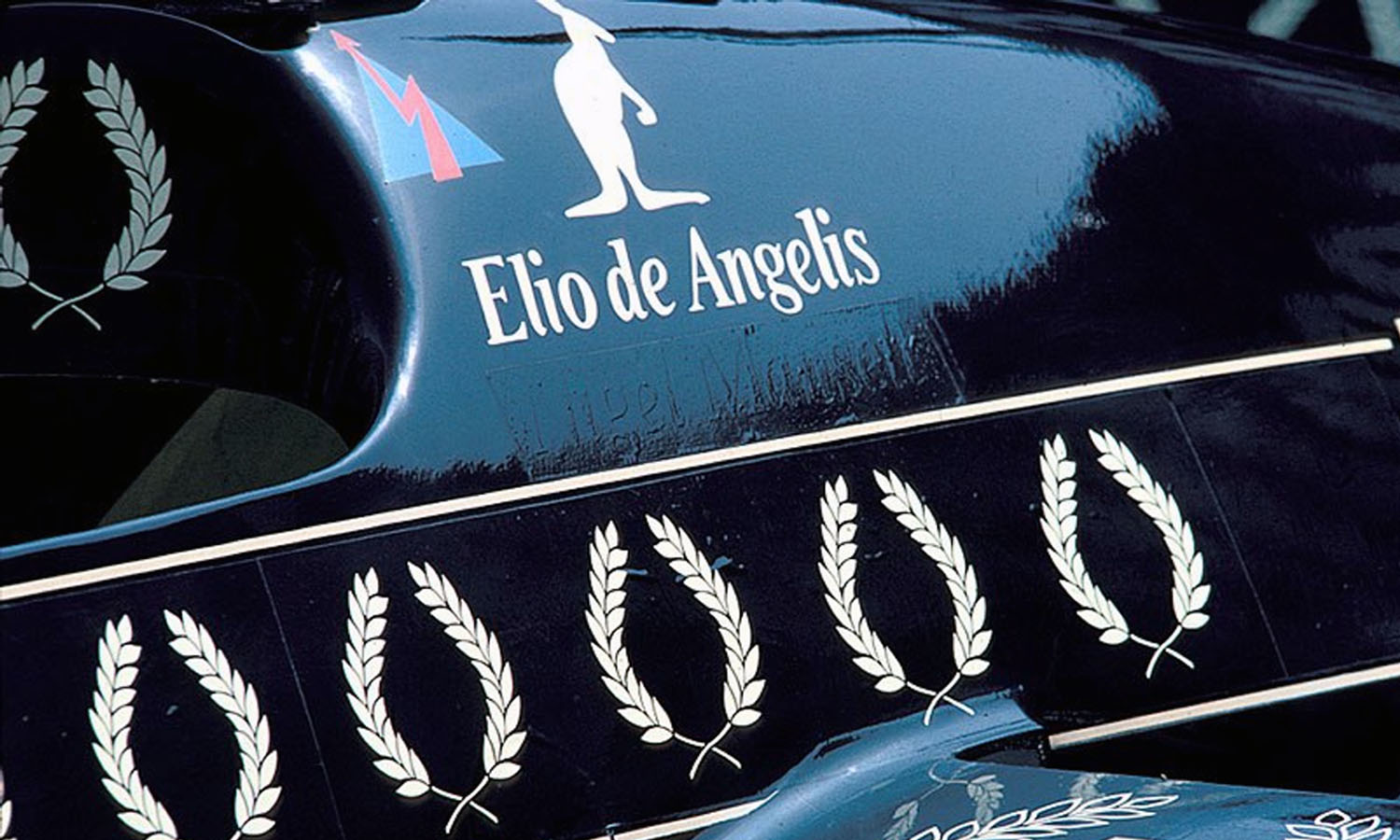

AFTER FIVE YEARS in F1, De Angelis is perhaps still looking for a precise location. Wrong cars, regulatory obstacles, a difficult relationship with the team have always characterized his seasons with Lotus. With the arrival of Gèrard Ducarouge, Elio’s career seems to have taken a more professional direction. The fact that he was able to have a winning car brought back that determination and fighting spirit that characterized his beginnings in Formula Three, and that the last few seasons with Lotus had overshadowed.

Five years have now passed since your Formula One debut at the 1979 Argentine Grand Prix: do you think you have shown your full potential?

Absolutely not. When I had a winning car, I don’t think I was out of shape in any situation. The truth is that, apart from a few sporadic races, I have never had a truly competitive car. Perhaps this is the first year where I am not in a situation of technical inferiority.

Six years in contact with English teams: what are the problems?

There are all the advantages of an English way of working, but also all the disadvantages of coming from a country with a completely different mentality like ours. In the past I have had several problems with the English press, with sponsors and with team managers. Now things are calmer, perhaps because I’m becoming English too.

For your image, do you think the debut in Misano in F2 was more important, or the victory in Montecarlo in F3?

Definitely the victory in Montecarlo. Personally, I remember the Misano race more with nostalgia. I came from F3, no one knew who Elio de Angelis was, to precede already established Formula One drivers in the race was a great satisfaction. There weren’t many excuses in Monte Carlo, I had to win at all costs.

That day in Monte Carlo you started with an almost last-ditch mentality, victory was the only chance you had. Don’t you think it would be better to have such pressure more often?

It is a difficult thing to say. At that moment I had to win by force, after the disappointments of Formula Two where I was playing my career, moreover F3 is a category where everyone is more or less at the same level. In Formula One there are too many variables, too many differences. Such a mentality would be dangerous. There are too many qualitative leaps between the various machines. You can call yourself Lauda, Prost, Piquet, but if you don’t have a winning car, you don’t do anything. Racing in F1 with the spirit I had in Montecarlo in F3 would lead to getting hurt as the only result.

So do you think that if you don’t have a winning car, it’s right not to give your best?

Exactly. Indeed, we should go even slower, since there are still accidents between cars fighting in the rear. A driver must give his all when he has a competitive car. You can’t expect who knows what from a car that runs slower than three seconds. You can go faster than your teammate, you certainly cannot expect to win the race. It is useless to risk for nothing.

So the exasperated risk you conceive only for the victory?

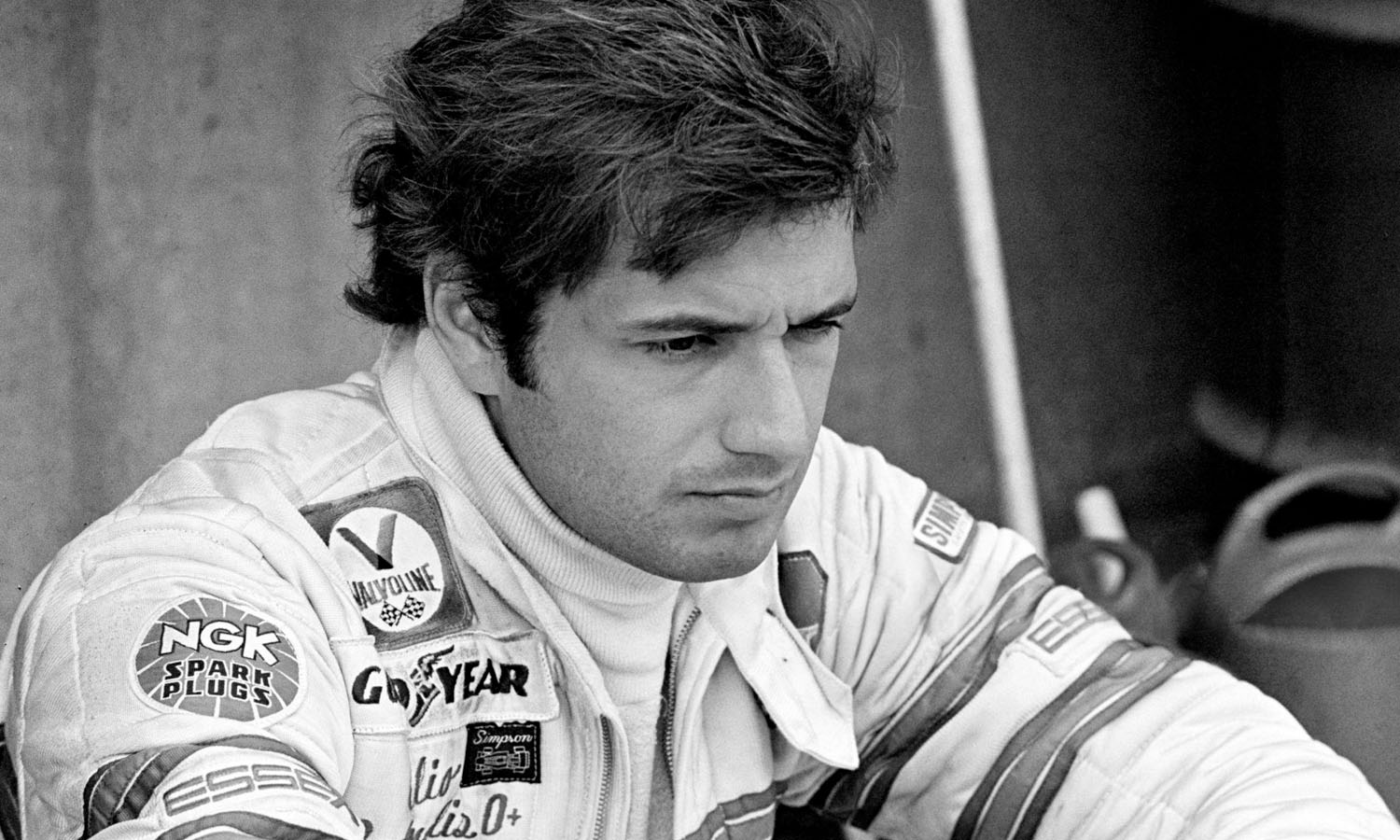

I do not consider the exasperated risk in any case. We must go to the limit, never beyond. The first year with the Shadow I ran with the mentality you say. I had no experience, I didn’t know that in Formula One you can get hurt a lot. I didn’t understand that when you have an accident, and you haven’t done anything to yourself, you have to thank luck. In my first year in Formula One I didn’t consider all these aspects, then when people die near you, you understand many things.

Not even in Austria, on the last lap for Rosberg, did you go at your best?

No, this is what few have understood. We both went to the maximum, but within the limit: we did not rotate. In qualifying, with the tires for some time, you sometimes find yourself almost an automaton, having as one thought only to push on the accelerator, but it is not a feeling that I like.

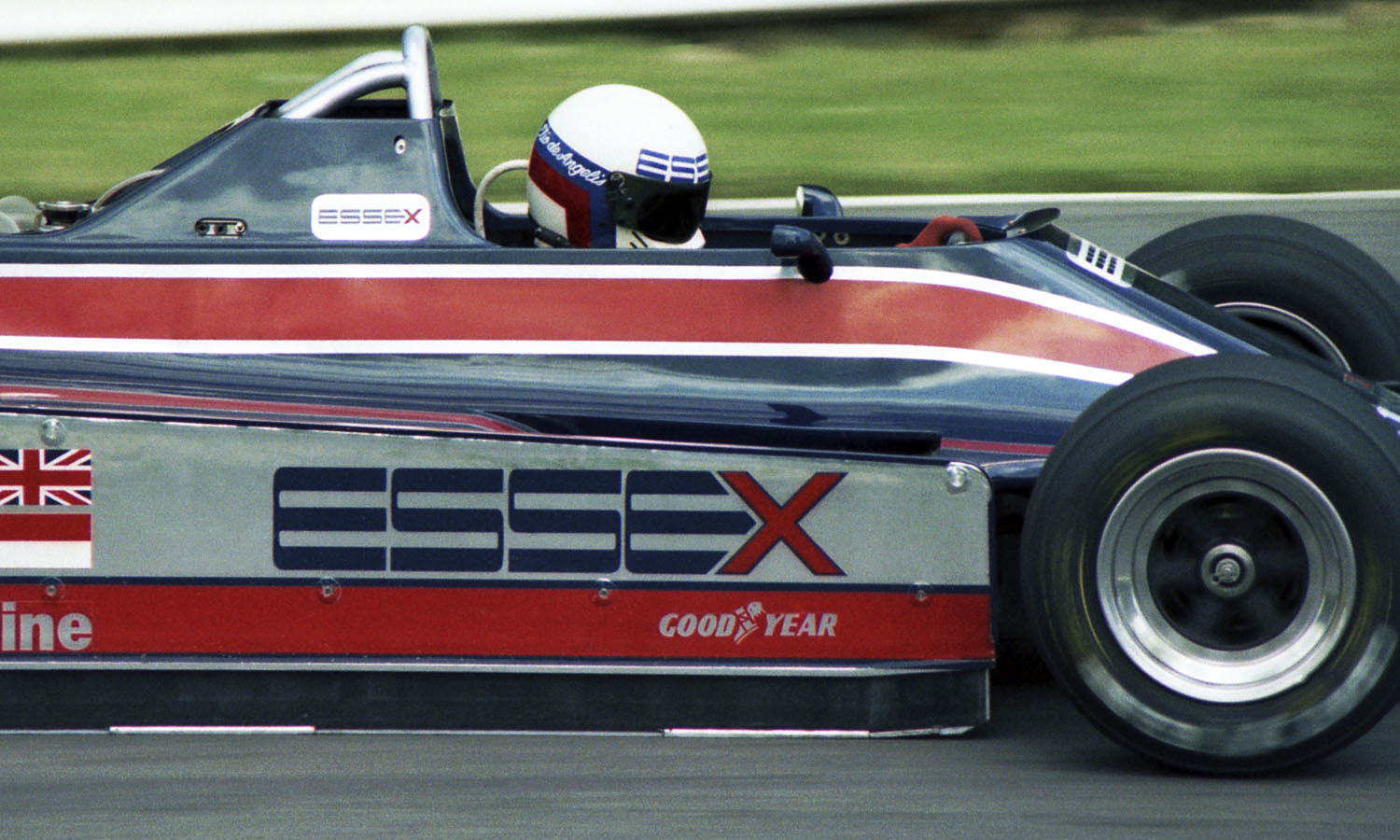

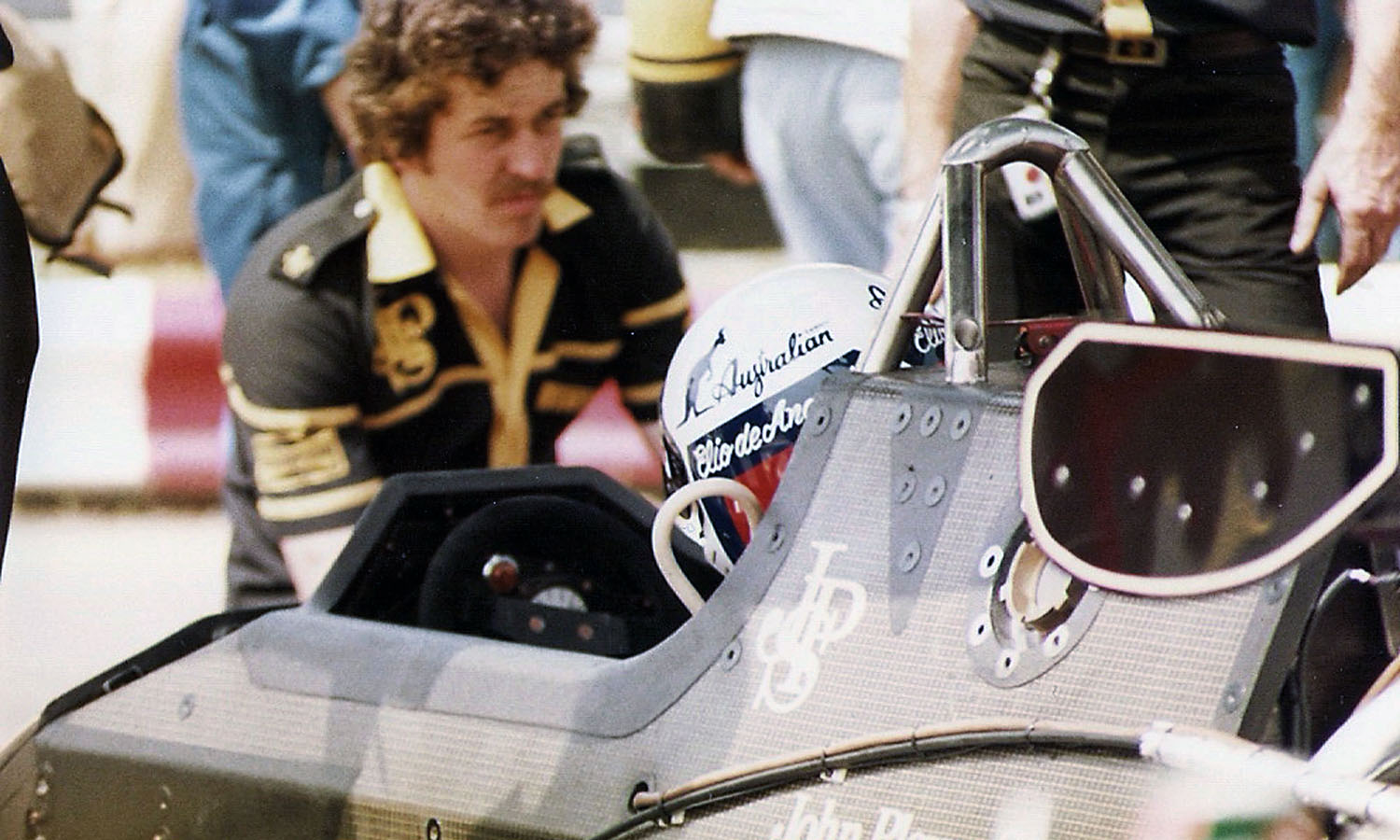

How does it feel to drive a Formula One at eighteen?

A great emotion, even if at the time I probably didn’t realize it. When I got on the T3 for the first time, I certainly didn’t feel like I had arrived. I knew that nothing would happen, that there were more experienced drivers than me. At one point it seemed that I had to replace Villeneuve. To race in that moment I would have done anything, but looking back I concluded it was good that this did not happen. I wasn’t ready yet, the times for an Italian in a Ferrari were not yet ripe. There would be too much pressure and I was too young to bear it.

Why did Colin Chapman choose you?

I think he was impressed by the races I did at Silverstone and Watkins Glen under the water with the Shadow. Then I was the fastest among the drivers he called up for the winter testings at Paul Ricard.

You came to Lotus to replace Carlos Reutemann: what did Chapman expect from you?

At that time any comparison would have been out of place. Reutemann was a driver who was racing to win the world championship, I was a beginner. I joined Lotus with a contract as a second driver, but as a second driver of the past, not like now. I had the spare car, the less powerful engines, I could not use the forklift. Overall I was faster than Andretti, even if honestly I have to say that maybe at that time Mario was already unmotivated. He was still the best team mate I ever had.

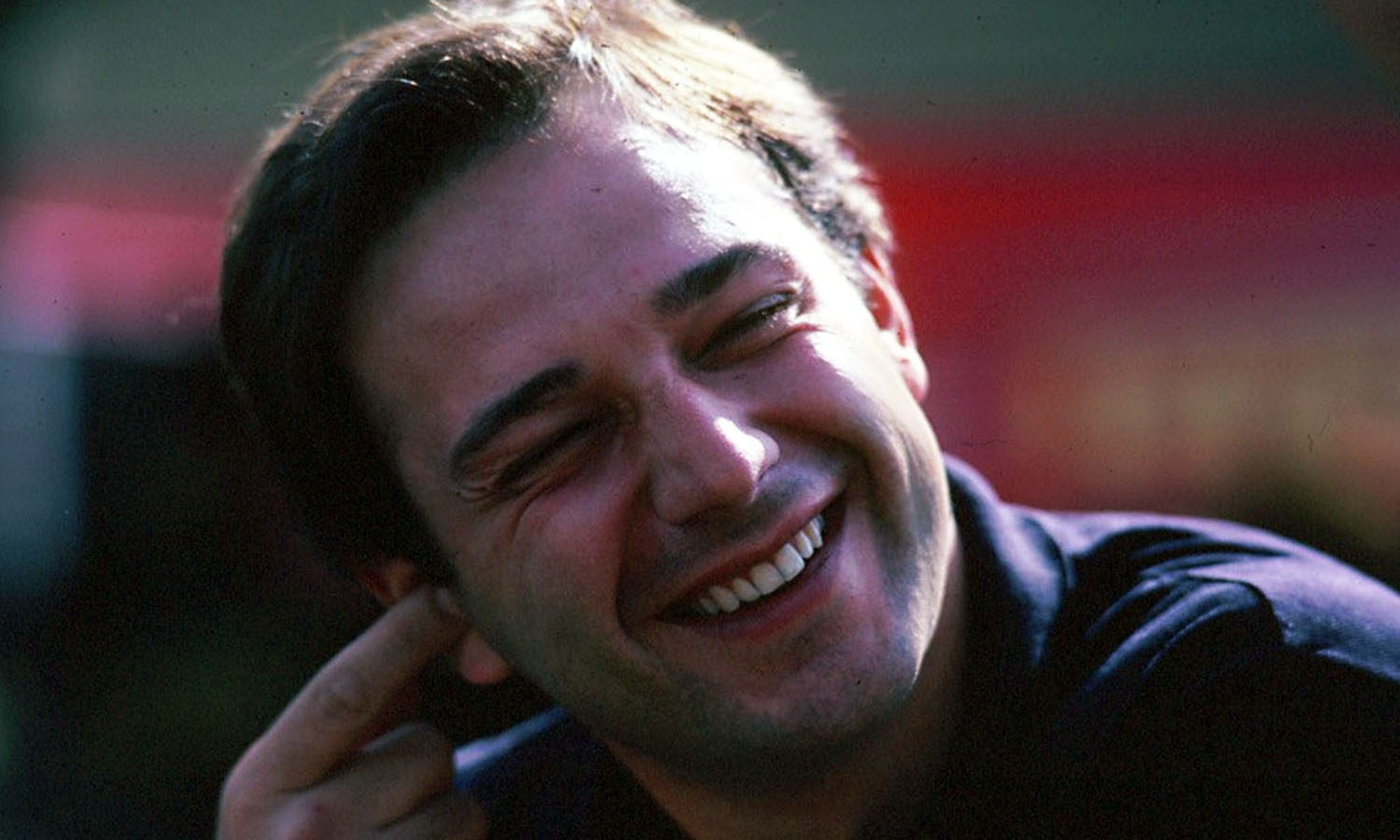

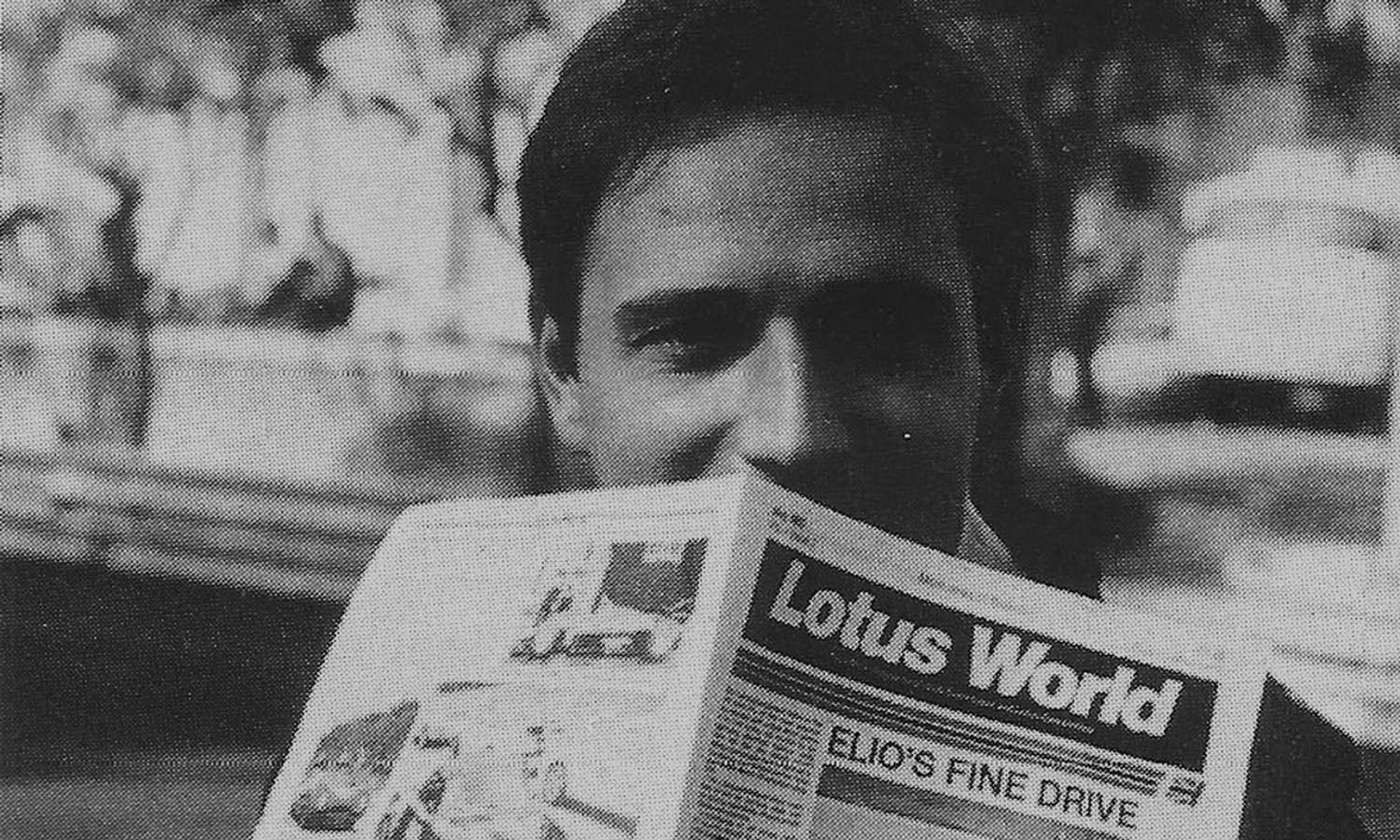

What memory do you have of Chapman?

Optimal. After my victory in Austria he had completely unlocked himself against me. Before, having practically had the best drivers in the world, he was waiting to see how I would perform in a winning situation. I think that after Zeltweg, Chapman had found all the incentives to want to grow up again. He had a difficult character, in the past there were also arguments, but always on a technical level, never on a personal level. In some aspects we had a very similar character. He was like a father to me.

For Lotus you also drove the “88” model, a car that could open up new developments in the field of automotive experimentation…

Exactly, I believe that, developed, the Lotus 88 could really give a change to the whole Formula One. It was rejected at the regulatory level, only because everything that came from Lotus was looked upon with distrust, prevention. Like the reputation that Lotus were fragile and dangerous cars. This may have been true in the past, when Chapman could only fight opponents with the weight weapon. I can safely say that with the Lotus I had some accidents that I don’t know if I could have told about them later with the other cars.

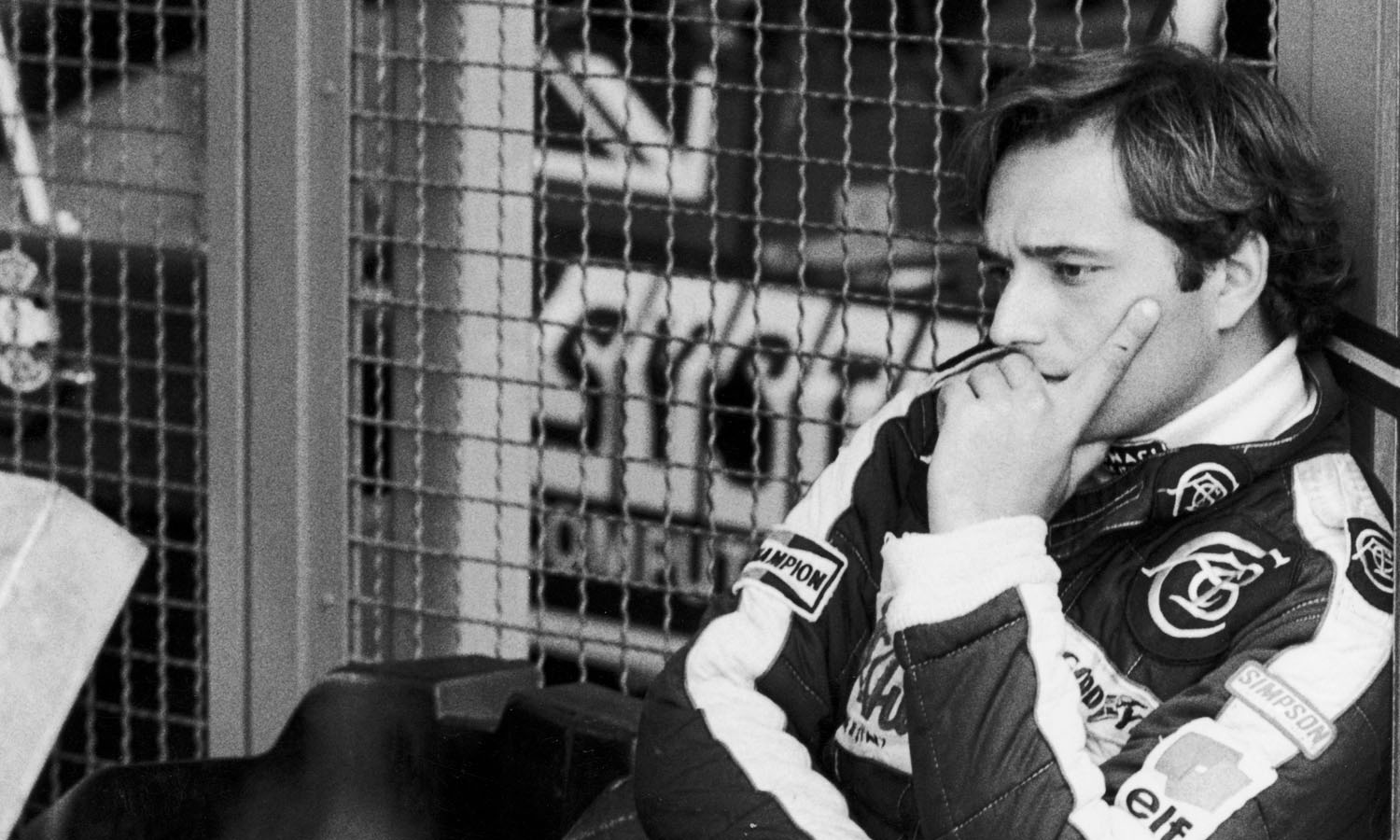

You have often complained in the past about the treatment received by the team. Have things changed this year?

At first I was perhaps too impulsive, I openly complained if technical injustices were done to me. For this I have also had some reproaches from my team. Over the years in Formula One you become more political. This environment may have wanted me to change my character. Of course when there are episodes like South Africa when, after I was the fastest in Rio, I was unable to perform well due to the KKK turbines, I lose my patience, I do not like to lose in front of others for faults not mine. Undoubtedly, they respect me at Lotus, however, knowing that the other driver is perhaps not up to the situation, they try to prepare the cars so that Mansell does not disfigure. After all this is understandable, Mansell is English, and every time he goes on television, for John Player it is a lot, a lot of money.

You signed a contract with Alfa: what happened?

I had three contracts signed with Alfa. When everything had been planned, at the last moment the Alfa backtracked; but looking at how things are going today, I think it was better for me.

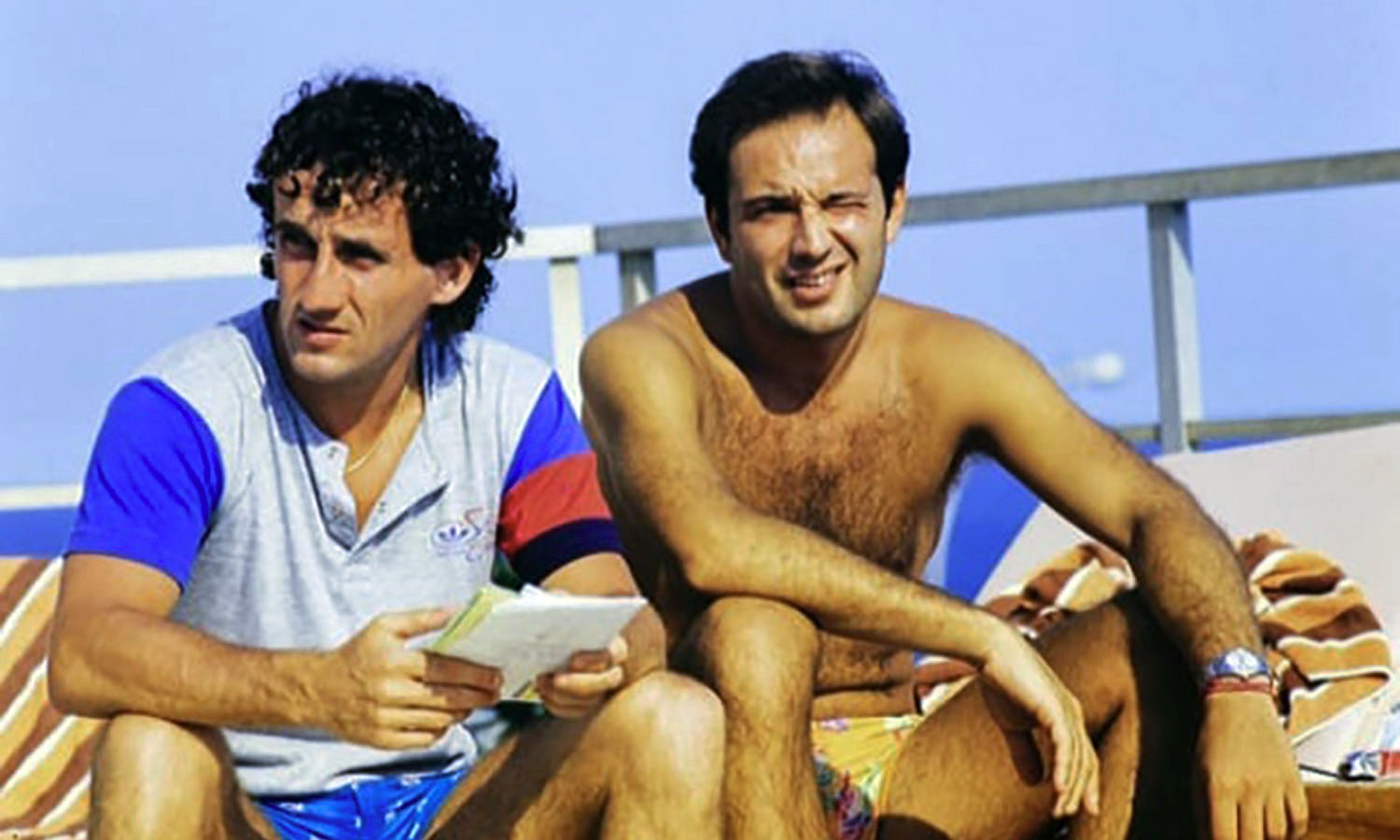

What does Alboreto have more than the other Italian drivers?

He is more diplomatic.

In the past you have often criticized Villeneuve. Didn’t you share his way of interpreting Formula One?

It was not to be a seer, but I had always said it: driving in that way it was inevitable that what happened then happened. Driving like that takes unnecessary risks, not necessary for the performance of the car.

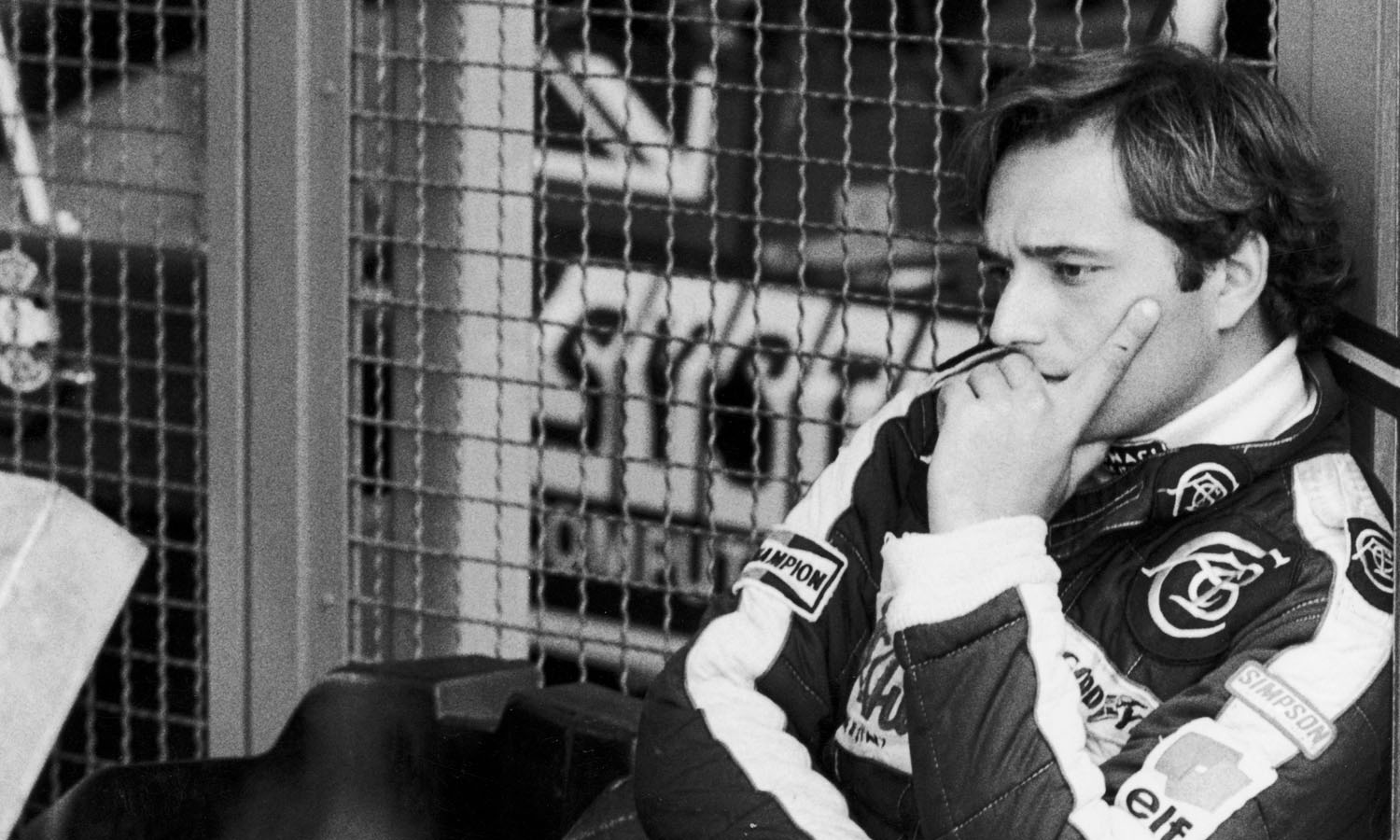

Does the image of the playboy driver bother you?

This is a label that they have given me, but which I do not consider absolutely true. As a spirit, as a way of interpreting life, I feel very close to Clay Regazzoni. In this, perhaps I am different from the other drivers.

Do you get old quickly in Formula 1?

It is true. Every mistake pays off, everything is very difficult. To live in this environment, you must necessarily accept certain rules. Experiences are made, certain extreme situations are experienced in a few years, which a normal person faces over a lifetime.

Do you think you will be racing for a long time?

I do not believe. I am now twenty-six and have competed in nearly eighty grand prix races. In ten years I would still be young but I would have raced twice as many as I am today, which is crazy. The further you go, the more being a driver becomes a heavy thing. Not for what concerns the driving, but for everything else, the travels, the pressures. At the beginning there is the charm of novelty, it is a whole world to discover, you have much more enthusiasm. Now I know perfectly well which hotel I’m going to, which faces I’ll see, everything becomes routine. The only thought is about the machine and the performance it can give you. When these benefits don’t come, I get tired. Now I enjoy racing less. It becomes a beautiful thing only when the car is good, because you strive for success. The thrill and excitement of the five hundred horses behind my back have passed long ago.

© 1984 Autosprint • By Cesare Maria Manucci • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended