The massive promotion of French drivers in Formula 1 has been one of the major facts of the past seasons, seven French in Grands Prix: it was a privileged situation for a country. Enviable. On the other side of the Channel, we have sometimes made faces by considering the number of "froggies" in F1 to be a little too high. In France, we have, not without reason, somewhat gargled about this situation. Everyone has boasted about it, even if it is due almost solely to the deep action undertaken for many years by the oil company Elf.

Translated by this website

Of the seven most regular French players in the Grands Prix, five have benefited more or less directly from the policy pursued by this oil company (driving schools, promotion formulas, alliance with Renault for the development of the V6 Gordini engine); they are Depailler, Jabouille, Tambay, Arnoux and Pironi. The other two (Jarier and Laffite) did not follow the same path, as did Patrick Gaillard. But it is not impossible that they benefited in part from the momentum generated by Elf for the benefit of motor racing in France. But since the “France F1” spaceship has been in orbit, a decompression phenomenon has occurred, and we do not see the massive arrival of the elements likely to ensure the relay.

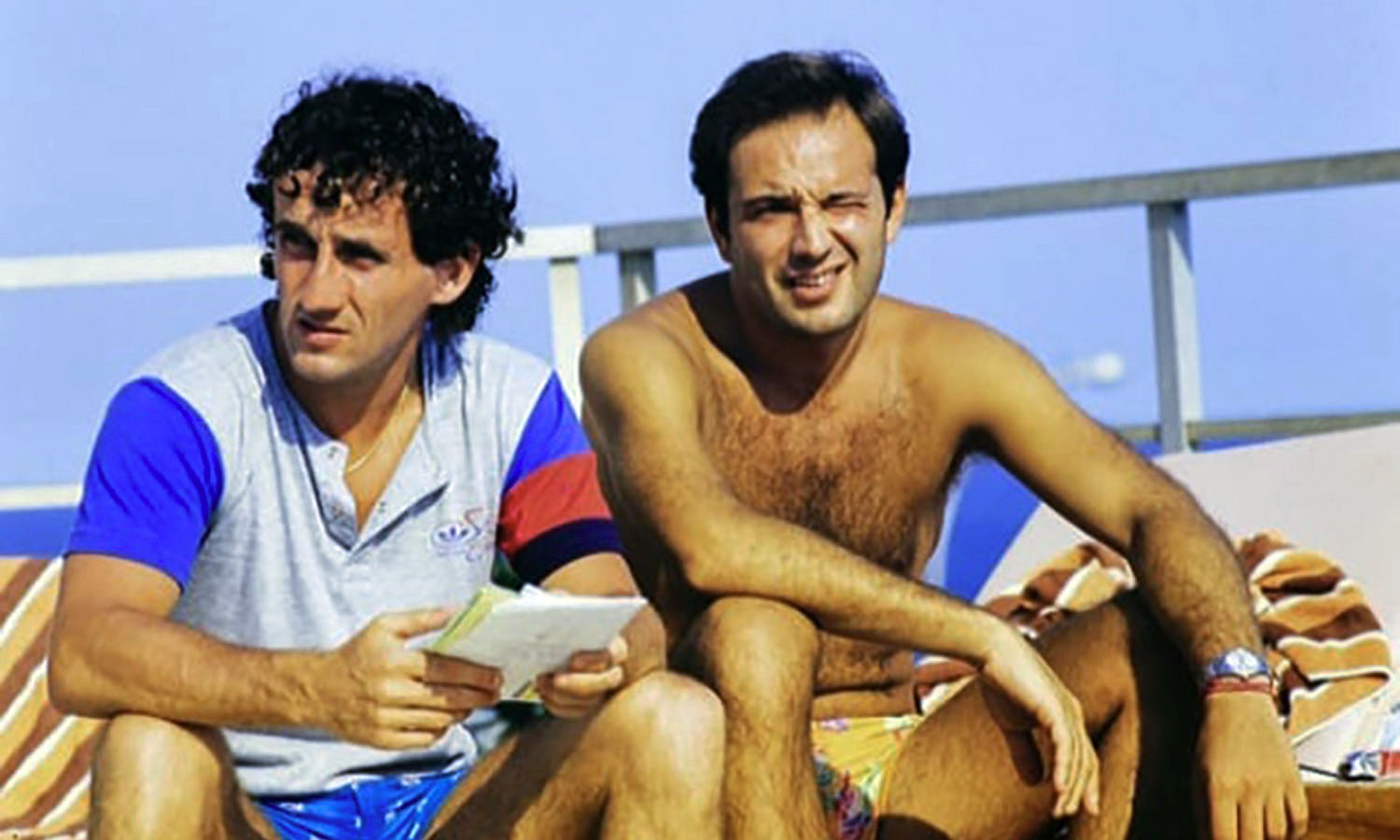

Only Alain Prost has succeeded in breaking through, but at the cost of what talent, and what patience!

Meanwhile, on the other side of the Alps, a movement of profound magnitude was formed, which gave birth to the Italian “new wave”.

This country which, at the creation of the world championship (1950), had been the cradle of F1 with Ascari, Farina, Villoresi, Taruffi, then the young Castellotti, Musso, Perdisa, had ended up being eclipsed by England. and its Anglo-Saxon satellites. Certainly, a breakthrough had taken place in the sixties with Scarfiotti and especially Bandini, but after the dramatic disappearance of these two champions, nothing or almost nothing left: the promising but alas short-lived Giunti, then the hard-working Merzario and Brambilla, but these two veterans have never had assets allowing them to showcase themselves at the highest level.

However, a movement was being created, under the impetus of dynamic leaders, whose first fruits have recently emerged. In 1979, the Italians came second to the French in terms of numbers, with the two “old-timers” (Merzario and Brambilla), as well as three real hopefuls: Patrese, Giacomelli and de Angelis. And that’s not all: Fabi, Colombo, Gabbiani (in F2), Ghinzani, Alboreto, Baldi, and many others (in F3) bode well for the future for Italian drivers.

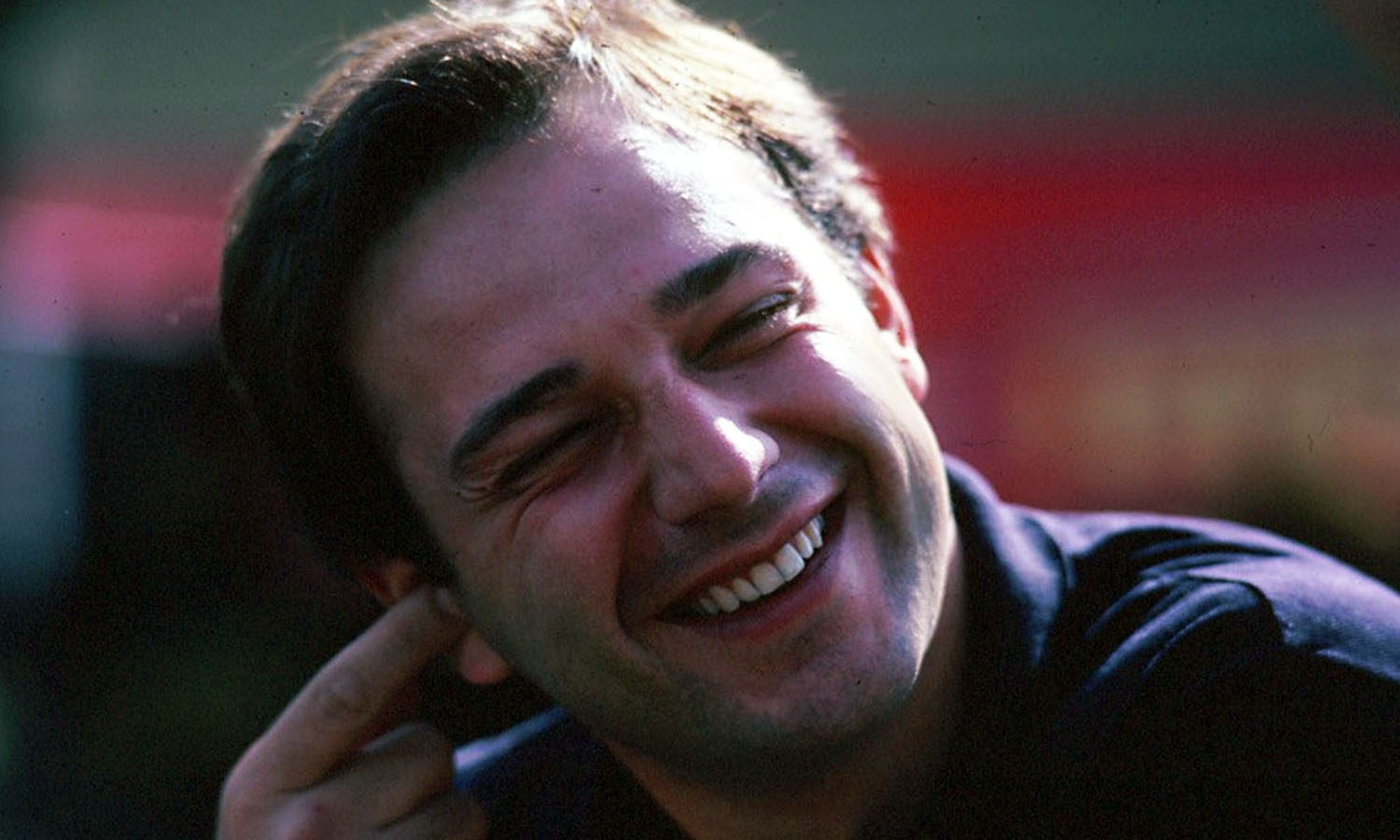

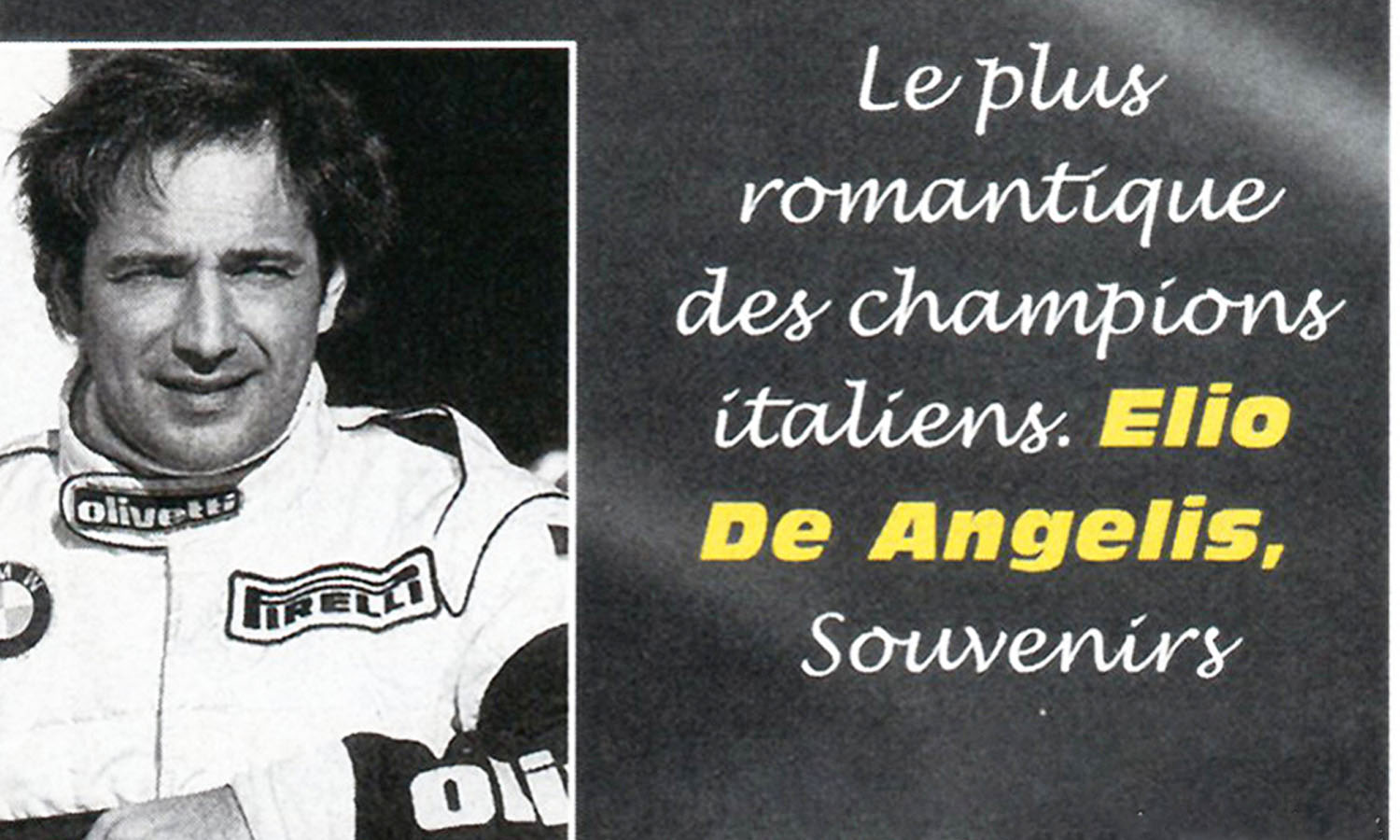

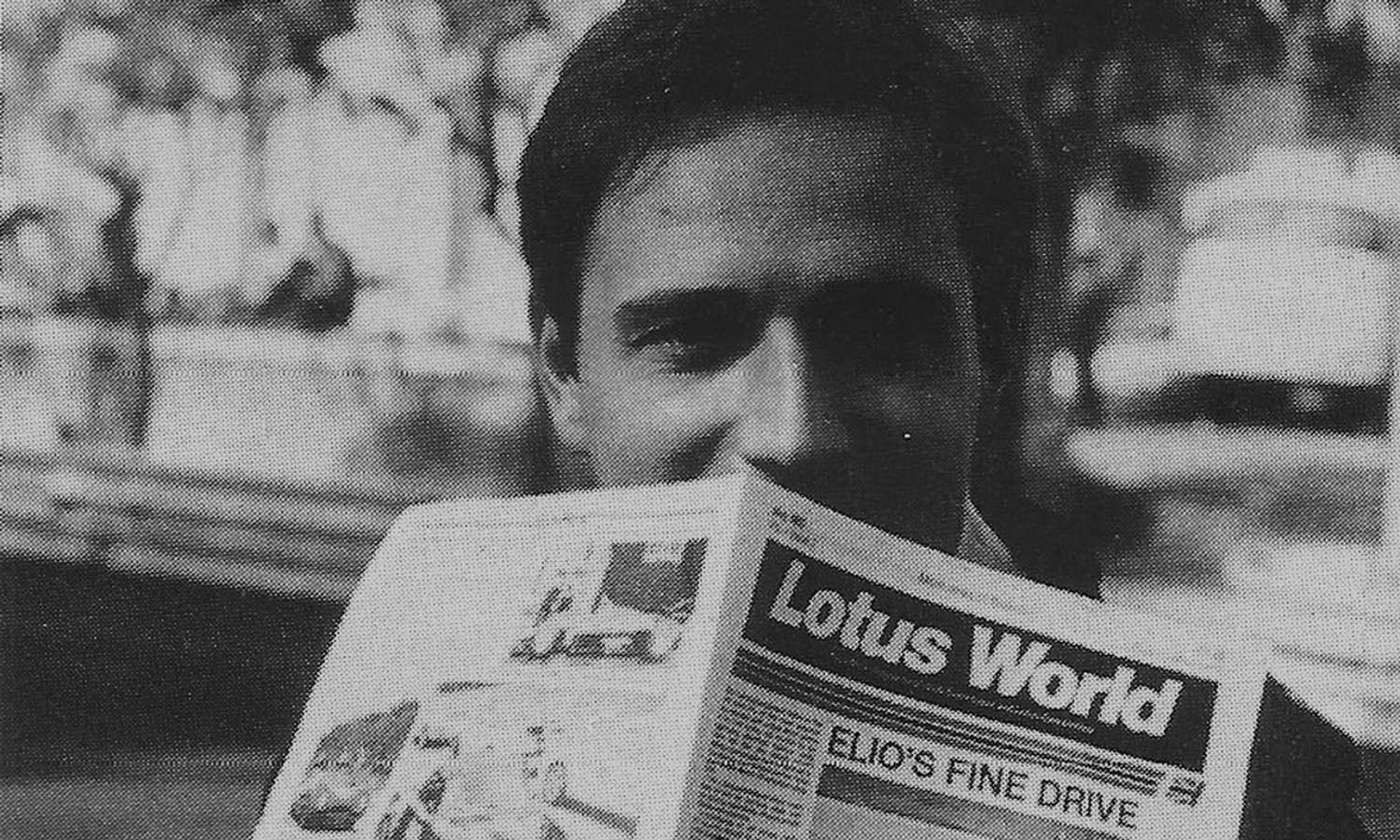

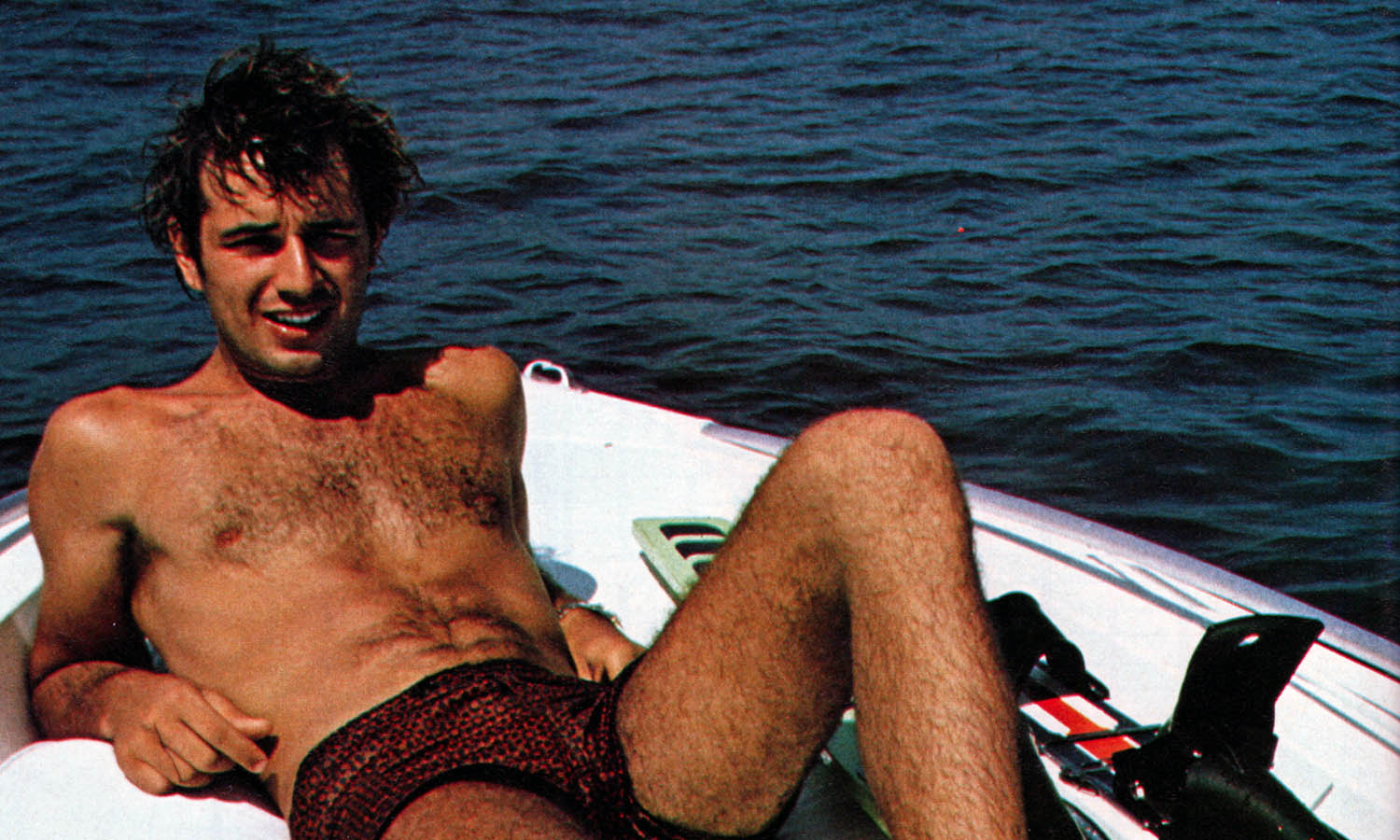

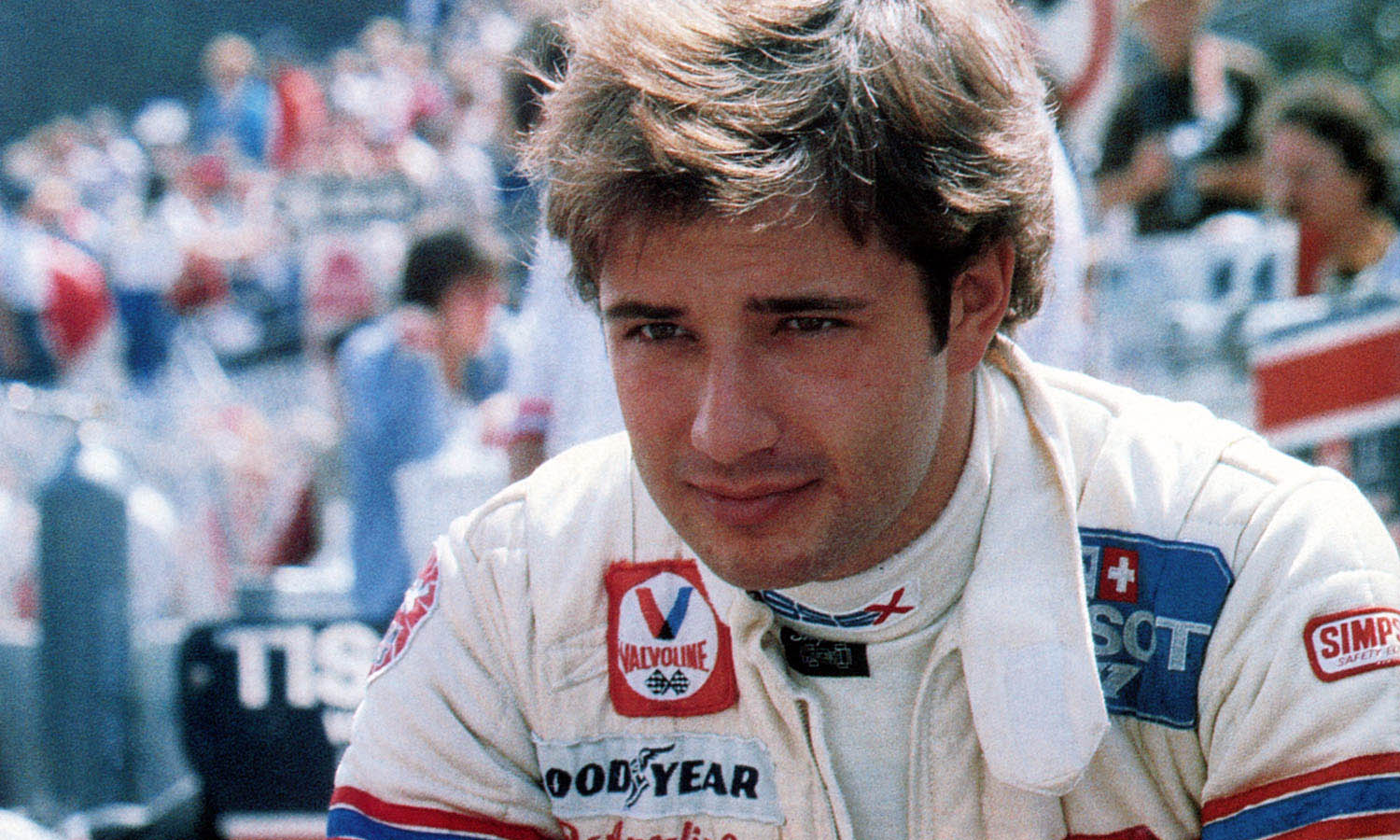

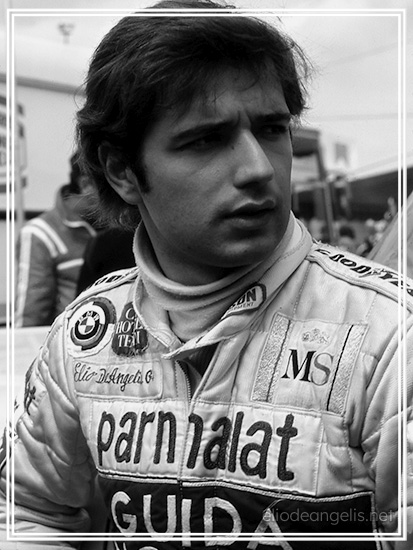

Privileged

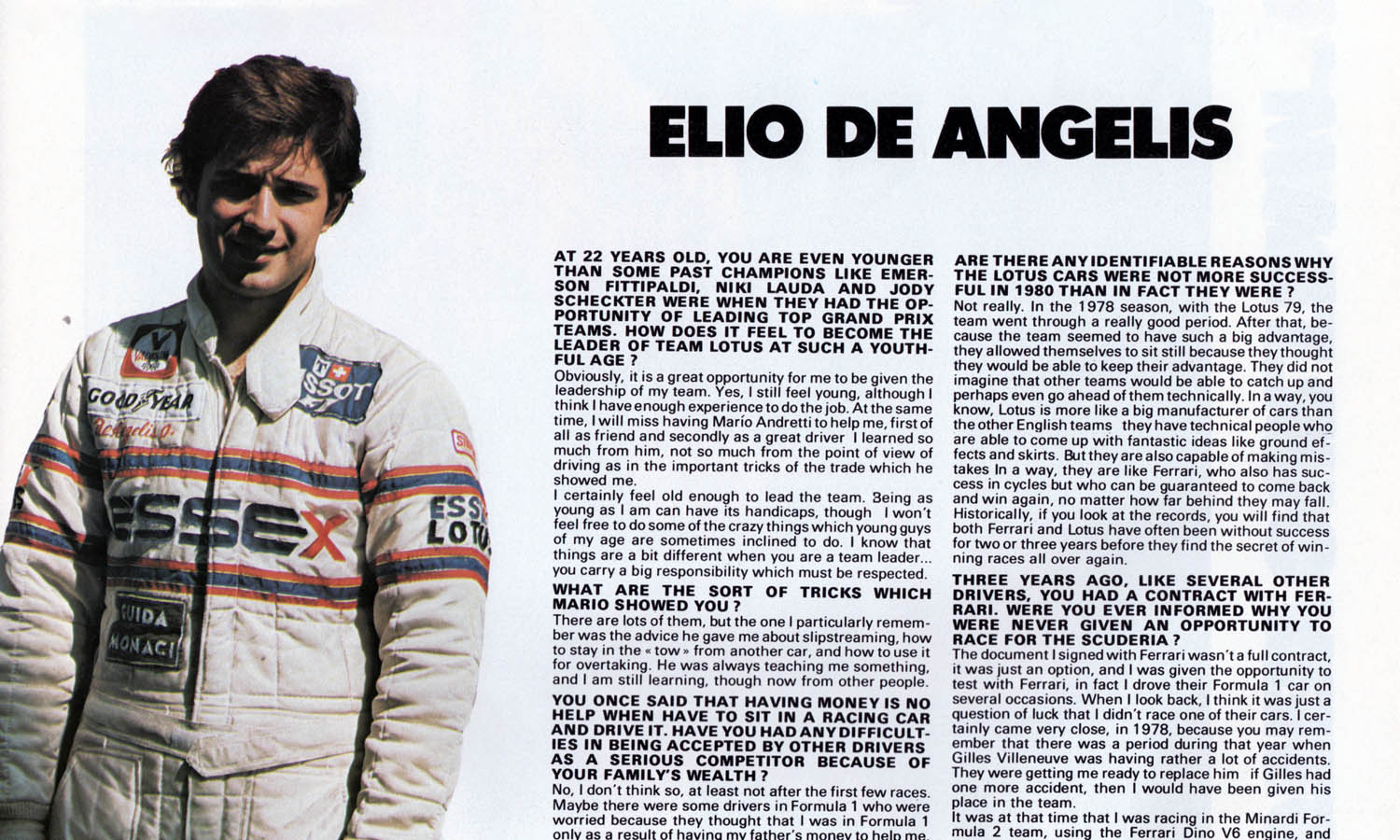

In this splendid line-up, Elio de Angelis occupies a special place, privileged he is one of the youngest of all, and he has already entered F1. And why hide it, he makes us feel he is one of the most gifted in speed driving. He did not have a marvelous car in 1979 with the Shadow DN9B, but in several circumstances he was able to perform wonders at the wheel of this machine, which was nevertheless unwieldy and poorly efficient. Buenos Aires, Silverstone, Zeltweg, Watkins Glen were all opportunities for him to accomplish amazing feats. Of course, his efforts have rarely been crowned with success. There is the essential fact that the Shadow DN9B could hardly compete with the best “wing cars” – Ligier, first, then Williams and Renault, not to mention the Ferraris. And then you can’t have fun flirting with the limit with impunity when you go about it with the arrogance, the contempt for the risk that he has shown, without sometimes suddenly getting to know the decor. By his behavior, this handsome, gifted Roman reminded us of the romantic driving of Castellotti and Musso, the heroes of the Ferrari and Maserati teams of the 1950s. De Angelis had not yet been born when these two piloting artists thrilled Grand Prix spectators with their audacity, and female spectators with their archangel profile!

When he was born in Rome on March 26, 1958, Castellotti had already killed himself – in Modena, in private testings. And Musso was soon to experience the same fate in Reims, in the race. Elio de Angelis therefore never had the opportunity to admire these two talented men in the exercise of their profession. However, he proceeds in the same way as them, perfectly combining the technique of driving with an elegance of style which few drivers can boast of, their common Latin origin could possibly explain it, one would be tempted, for example, to establish a parallel between their behavior in racing and the slightly supernatural, magnificent way in which some bullfighters manage to win the hearts of ‘aficionados’.

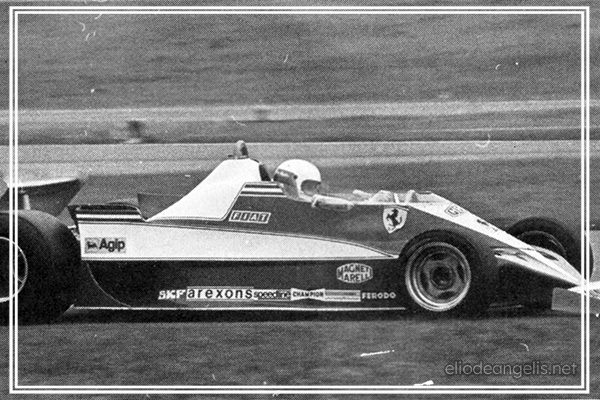

The first time our attention was caught by Elio de Angelis, whose name conjured up a gifted rookie among Italian F3 drivers – we were in Fiorano reporting on this fantastic private Ferrari test track. Villeneuve was to test Michelin tires at the wheel of a Ferrari T2. It was February 1978. At the same time as the Quebecer, another driver was there: Elio de Angelis, who was to work on the development of a Ferrari-powered Chevron. As soon as the F1 stopped, the Chevron F2 hit the track. Villeneuve, who was sheltering from the cold in the track control room, then followed Elio’s progress on the ticker displaying all the lap times, turn by turn.

Several times, Gilles was led to nod his head and say a few words of the sort: “Six seconds thirteen for the “S”, I don’t think an F2 could do better than that so far”.

Engineer Forghieri was there, ordering detail modifications to the Ferrari Villeneuve tested with his usual emphasis. In Fiorano, Forghieri is truly at home. When he was not testing, de Angelis came to watch the F1. At that time, Villeneuve was a rookie at Ferrari, and he had yet to acquire the authority he has shown that season. He even broke quite a bit of equipment, so much that the Italian press, always quick to ignite, began to question the value of the Quebecer.

De Angelis was not unaware of this situation, and he did not hide the attraction that the red car had on him. Suddenly Forghieri came up to him and said, “Tomorrow, if we finish our test program on time, you can drive the F1”.

A glint shone in the brown eyes of de Angelis, who couldn’t suppress an irresistible smile. Unfortunately, this long-awaited moment had to be postponed. It was snowing heavily in Emilia and all northern Italy when Elio jumped out of bed and opened the curtains of his hotel room in Modena the next day. He ended up driving the much-desired Ferrari, and even put in some promising performances with the new T3 at Fiorano, while Reutemann and Villeneuve were in another part of the world for a Grand Prix.

Ambitious

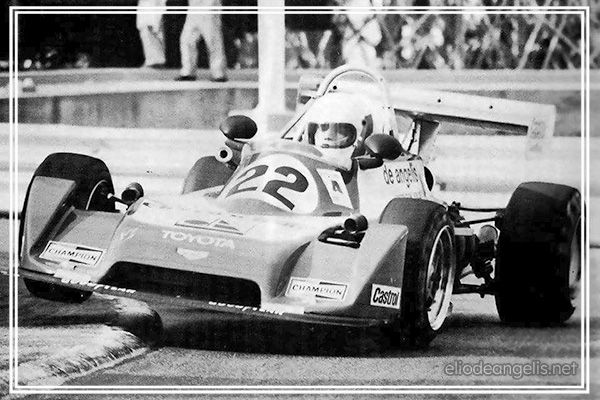

Second glimpse of de Angelis Monaco F3 in 1978. Elio had decided to face this event to restore his image, a season after revealing himself in F3. That day, Patrick Gaillard was a strong opponent for the Roman. The Frenchman led the operations with composure, and when he came back in his wake after a comeback led with authority, de Angelis seemed to have no other resource than to push his opponent to the fault.

But he is too ambitious, too eager to impose himself to be satisfied with such a deliberate tactic. In fact, de Angelis imposed himself in force on Gaillard, in a maneuver which he could have paid sliding alongside the Frenchman at the entrance to the Gare hairpin, where there is only room for one. You have to believe that the gods were with him when the wheels of the two Chevrons collided, Gaillard’s single seater was lifted before going to crash into the slides. That of de Angelis, fortunately, turned without a hitch. All Elio had to do was race to victory.

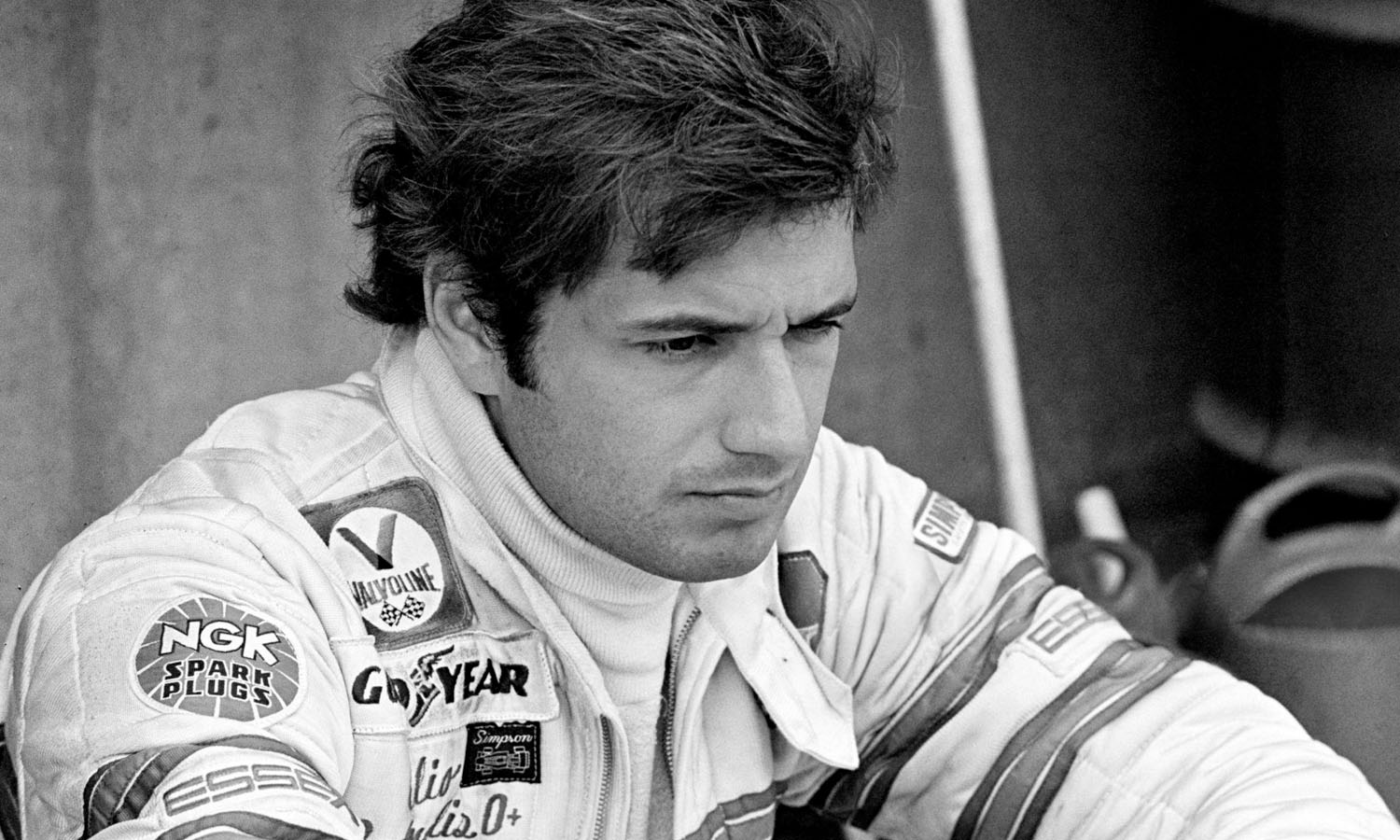

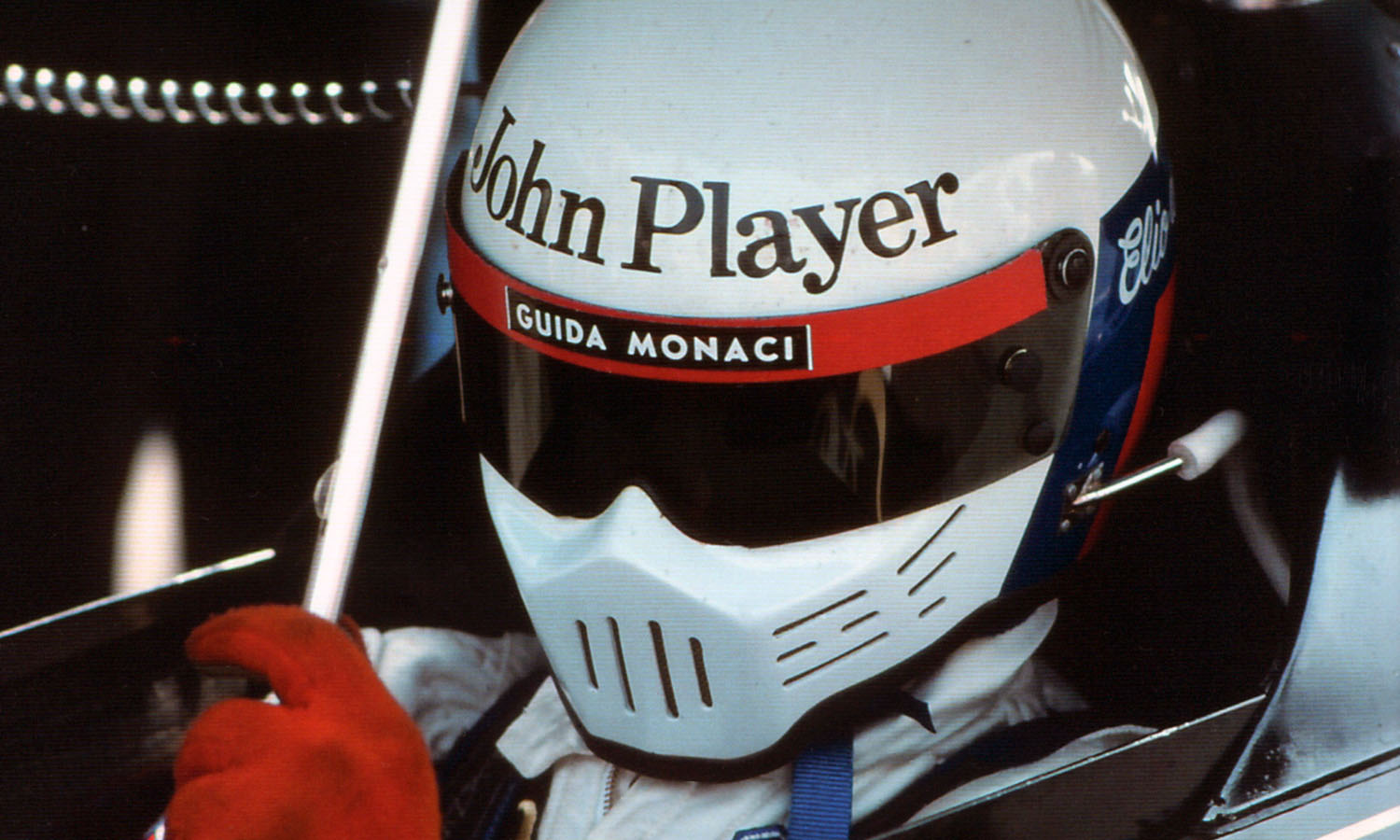

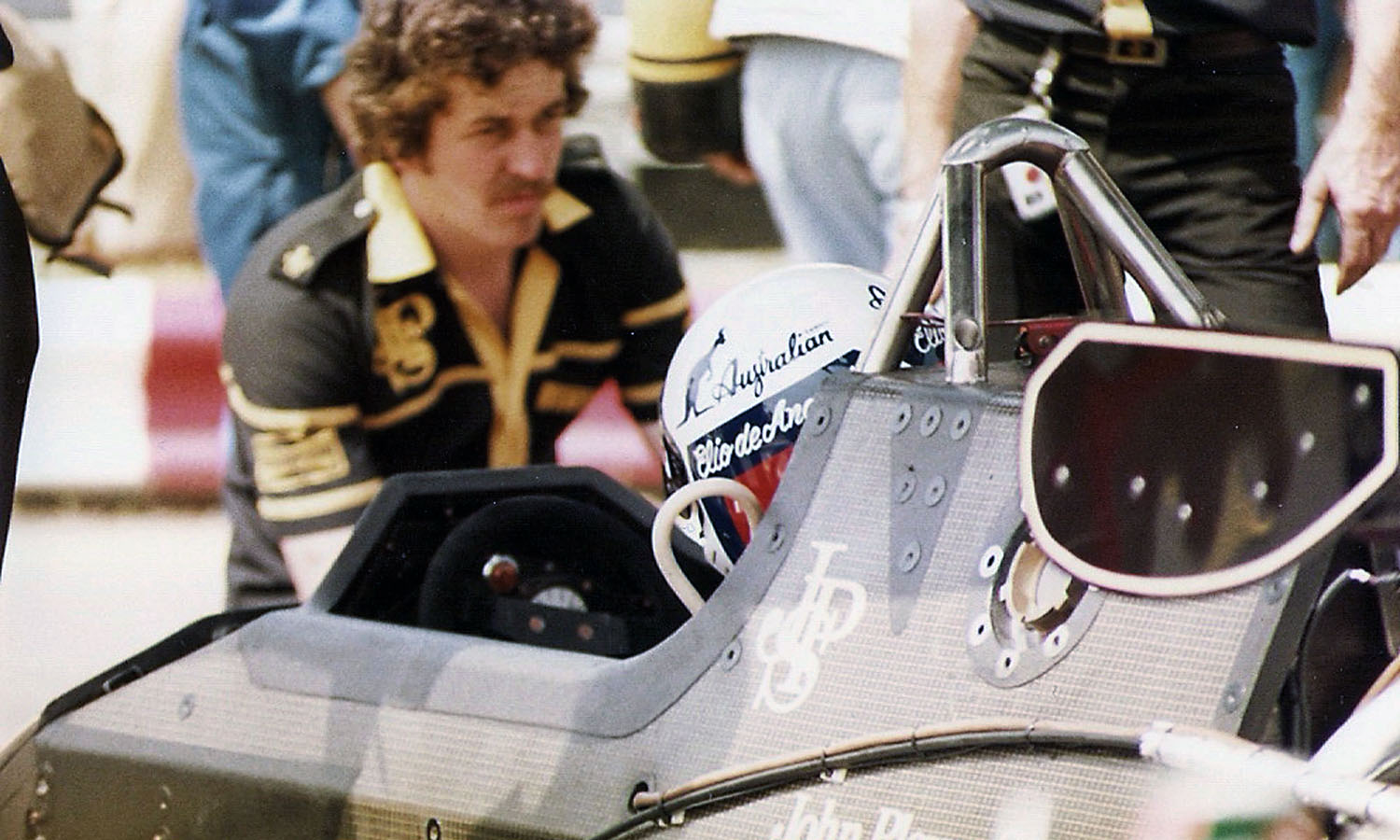

Third era during the fall of 1978, a year ago, when several F1 teams were testing on the Paul Ricard circuit. Shadow is there, with his two future drivers de Angelis and Lammers. Anglo-American team boss Don Nichols only has eyes and words for the Italian.

He tells us with a sincere tone of conviction: “I am convinced that de Angelis has a bright future ahead of him. We had him test at Silverstone in September, he was outstanding, faster than Regazzoni. He’s an exceptional driver”.

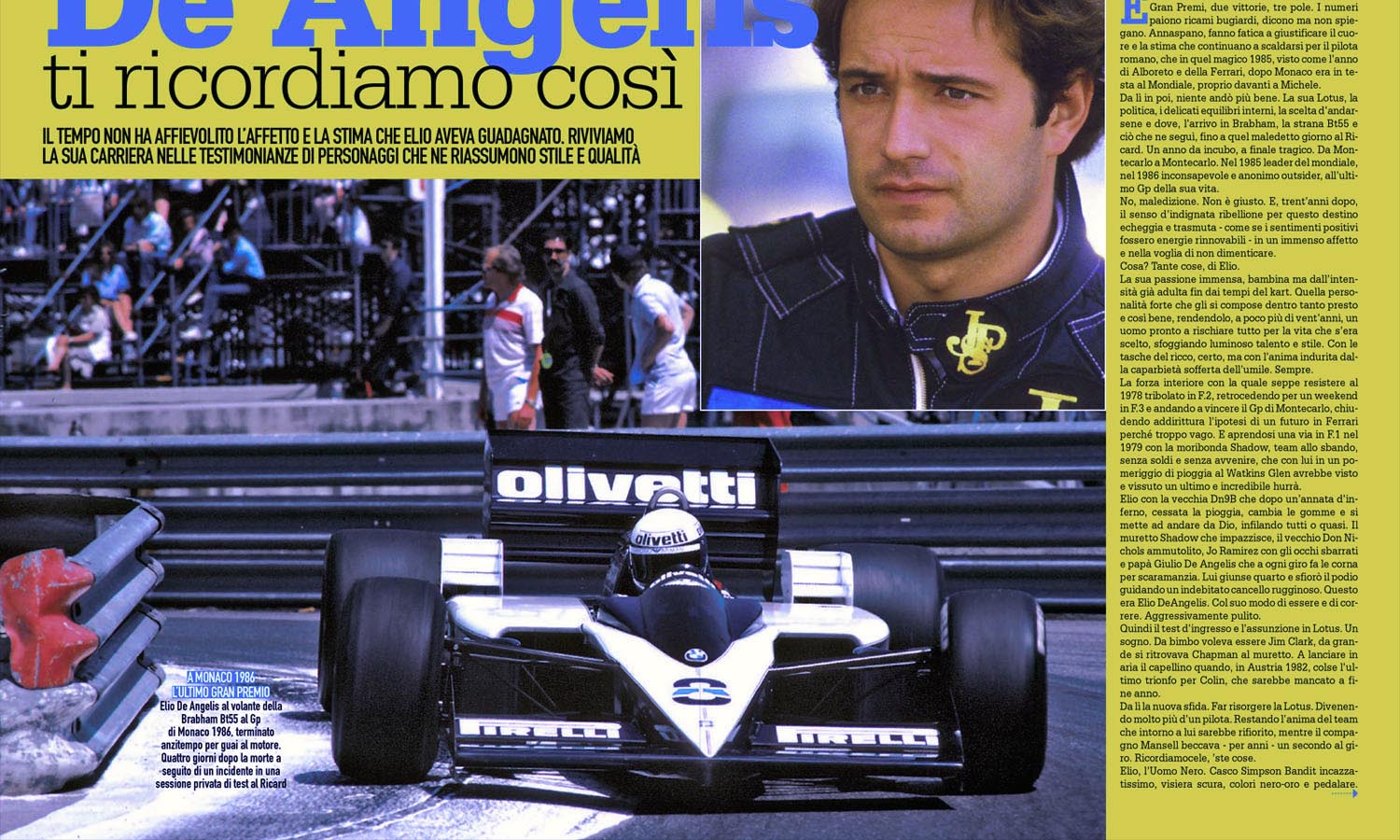

In 1979, de Angelis proved Don Nichols right through several authentic feats. Admittedly, Elio hasn’t always been able to make up for his Shadow’s lack of competitiveness. He even missed a qualification (Monaco). But when the circumstances were right, he performed some miracles at the wheel of his aging machine. The most obvious is probably Watkins Glen, where he magnificently exploited the lack of grip on the wet track to compensate for the usual lack of competitiveness of his machine. But the image of de Angelis that we prefer to keep from the past season is his start in the Zeltweg race. He outdid himself, that day, to register the clumsy black single-seater in the delicate difficulties of this circuit.

At the chicane (the best designed of all the circuits in the world) it was marvelous to see him literally juggle with precision and finesse, playing with the steering wheel and the accelerator to dominate his surly single seater with astonishing mastery.

Truly great art, where chance did not intervene, because with each passage Elio renewed his prowess. How, in moments like this, could we not have thought of the flamboyant driving of the Castellotti and Musso of our youth?

Karting at 14 years old

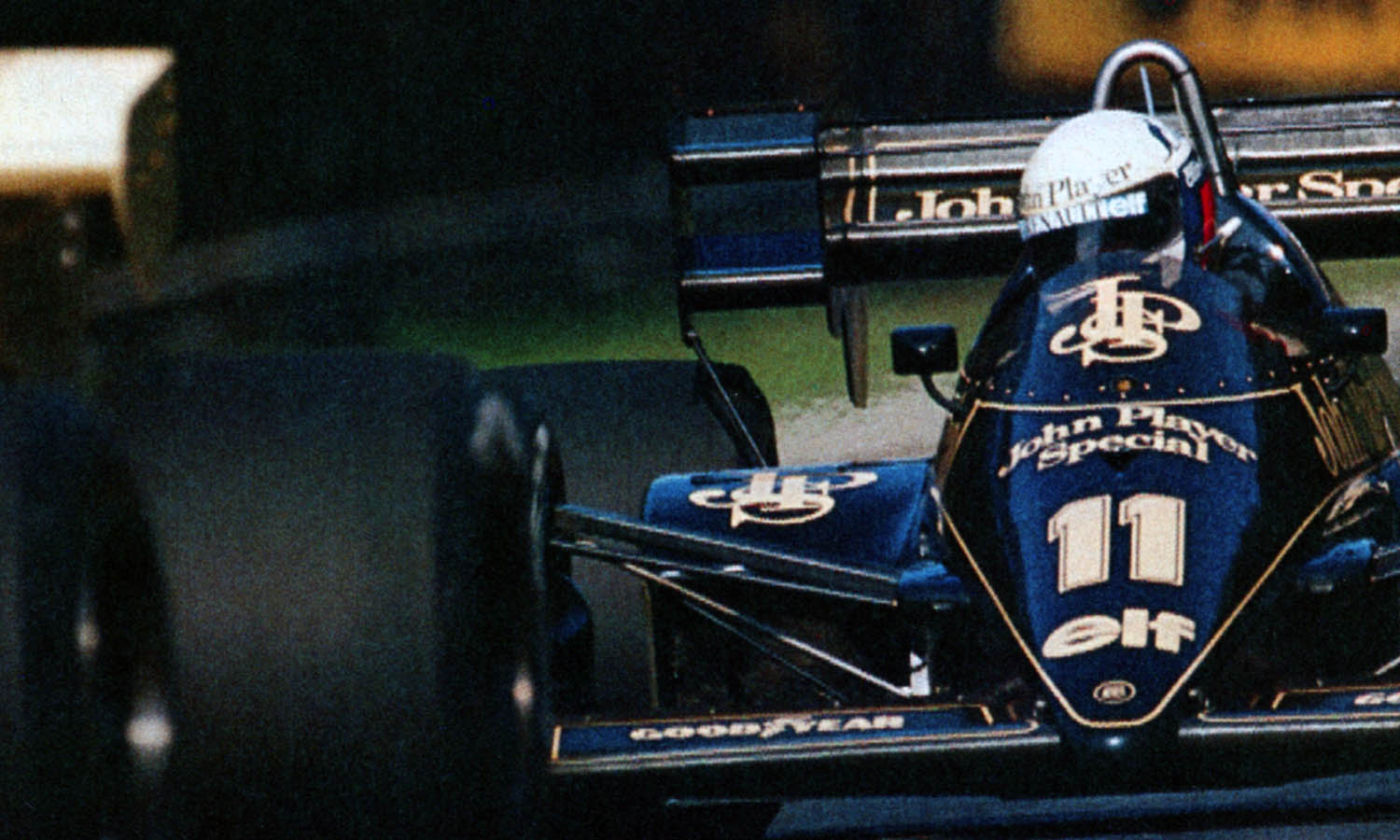

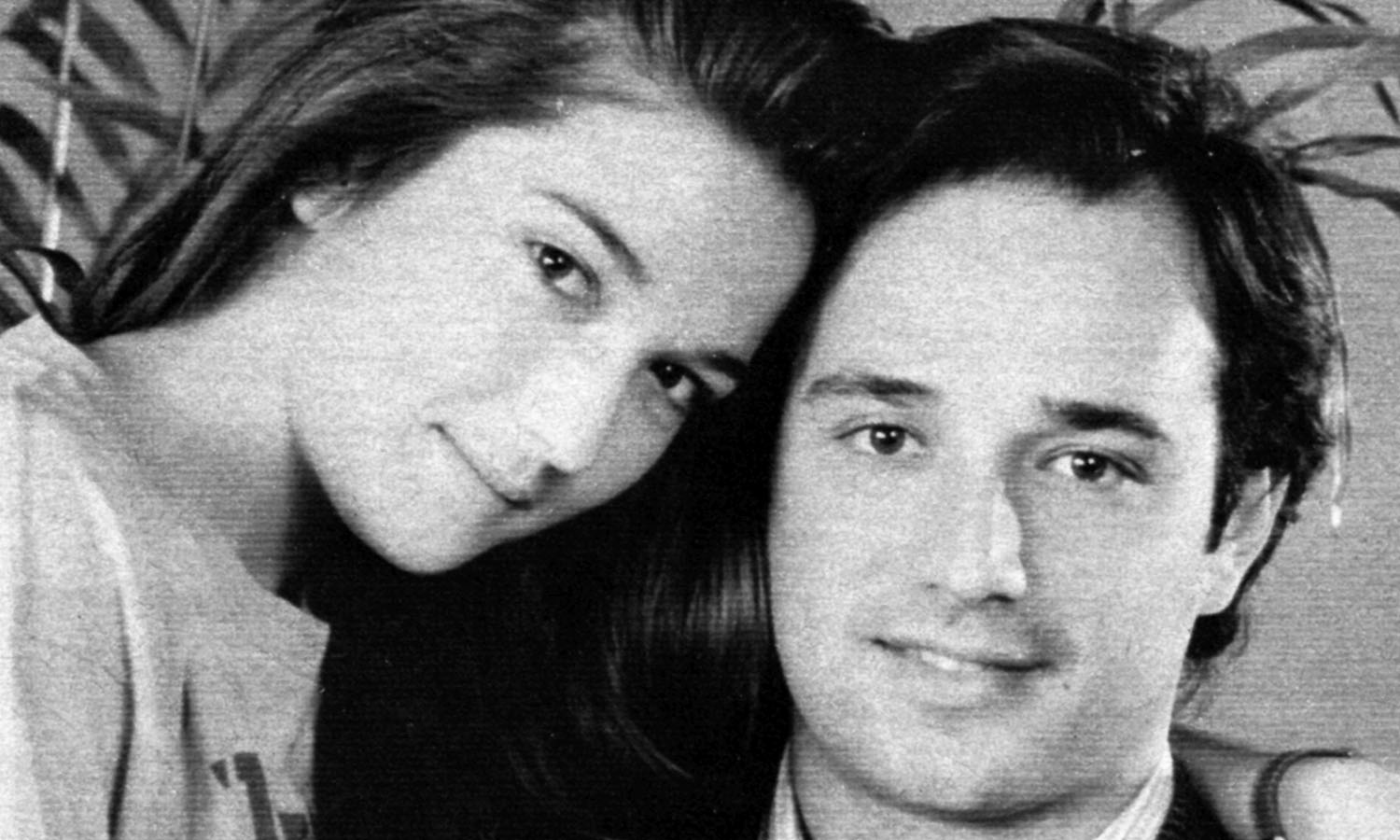

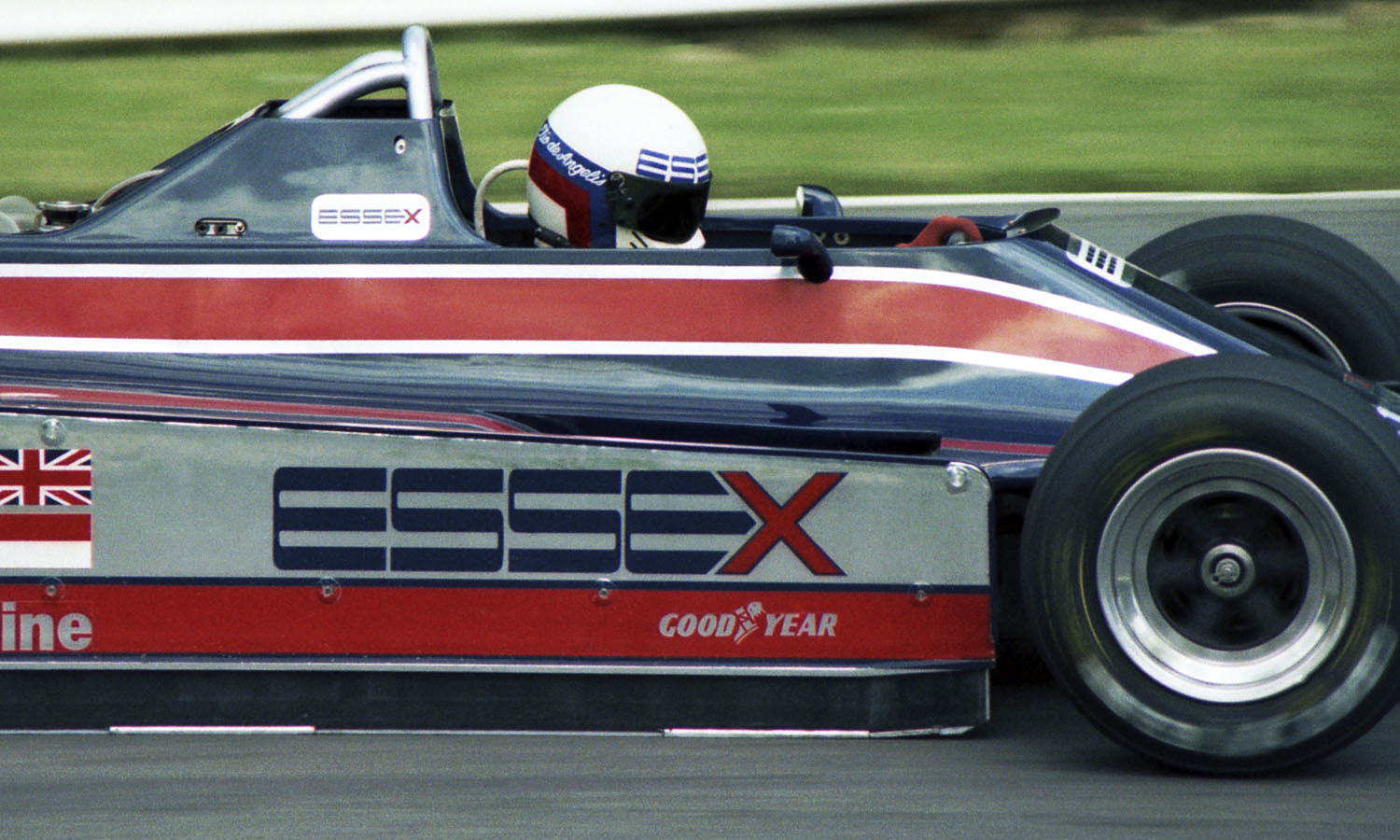

It was natural after that to want to get to know the author of anthological exploits better. The test he recently carried out at the wheel of a Lotus 79 on the Paul Ricard circuit gave us the opportunity to have a fairly long conversation with him. Elio de Angelis, son of a well-to-do family, handsome boy to boot, seems to bring together all the advantages that life can offer: calm, lucid, he talks about himself without embarrassment or boasting, in a clear way, a good intellectual and moral health.

“Born in Rome on March 26, 1958,” he says, “I was destined for architecture. But after a year I changed my objective, I enrolled in law. I also took economics classes. I obtained different diplomas in these various disciplines, but the race took precedence over studies very early on”.

When did the first inclinations concerning the race go back to?

At twelve years old, as soon as I had a certain maturity. Already, at the age of 8, I had a pedal car that I was passionate about. It was red, it was a replica of an old model Ferrari with a front engine. I was doing my own Grands Prix in the garden. There was a downhill driveway where I could pick up some speed…

And parental influence?

My father did not race, but he always had beautiful cars. When I was 14, my friends generally chose the moped to materialize their passion for motor vehicles and racing. I preferred go-karting. I started racing shortly after 14 years old, in 100 cmc. Eddie Cheever had started four months earlier and for me he was already a professional!

No attraction for racing as a spectator?

Yes, very much. I remember admiring Francisci, Regazzoni and Picchi in F3. And even Jacky Ickx on a Matra. In kart, I was Italian senior champion in the 2nd category in 1975, then the following year in the 1st category. That year I belonged to the Italian team, European champions with Cheever and Patrese, who had already taken up single seaters in Formula Italia. Among the good Kart drivers I raced against, there are still Gabbiani, Necchi, Prost and Goldstein.

The paternal help could not have been negligible. How did it translate in practice?

In 1977 my father bought me an F3, a Chevron. I did my first race at Paul Ricard. I started with an international license to which my track record in karting gave me the right. I had achieved the 6th fastest time in practice. In the race I finished 10th. My second race ended in an accident, it was at the Nurburgring, I was 2nd in the rain. Finally, in April, I got my first victory at Mugello. In Montecarlo I finished 2nd. My gearbox was damaged (first gear out of order) and I was unable to worry Pironi. But the Chevron didn’t often prove competitive and we decided to change it.

Pedrazzani, from Novamotor, insisted on the Ralt. We took it to Monza for the Lottery GP which I won, which allowed me to be Italian F3 champion. This race remains exceptional for me.

What about F2?

I had already had the opportunity to taste it that year (1977). The Everest team lent me a Ralt-Ferrari to race at Misano. I was 5th in practice and I stayed in the lead for 28 or 29 laps. Cheever was hot on my heels and we got hooked. In the second race I had tire problems.

I signed a contract with Everest for 1978, aiming to race in F2 with a Ferrari engine. In addition, I had an option with Ferrari for F1. We started with testing at Fiorano where I set the F2 record, but it was a difficult part. The British had not prepared a Chevron chassis specifically for the Dino Ferrari engine. We had to make an adjustment. Moreover, even at Ferrari, this attempt did not have everyone’s approval. The Commendatore was very attached to it because the engine bears the name of his son, but I don’t feel that his will to do something in F2 was followed fervently at the factory.

Oblivion

At Thruxton, it didn’t start badly (7th time in practice) but it quickly turned into a nightmare. The new cylinder heads could not be finished, because all the efforts were focused on F1, the chassis did not give satisfaction, and to top it off Goodyear completely neglected us for the good reason that in F1, Ferrari was allied with Michelin.

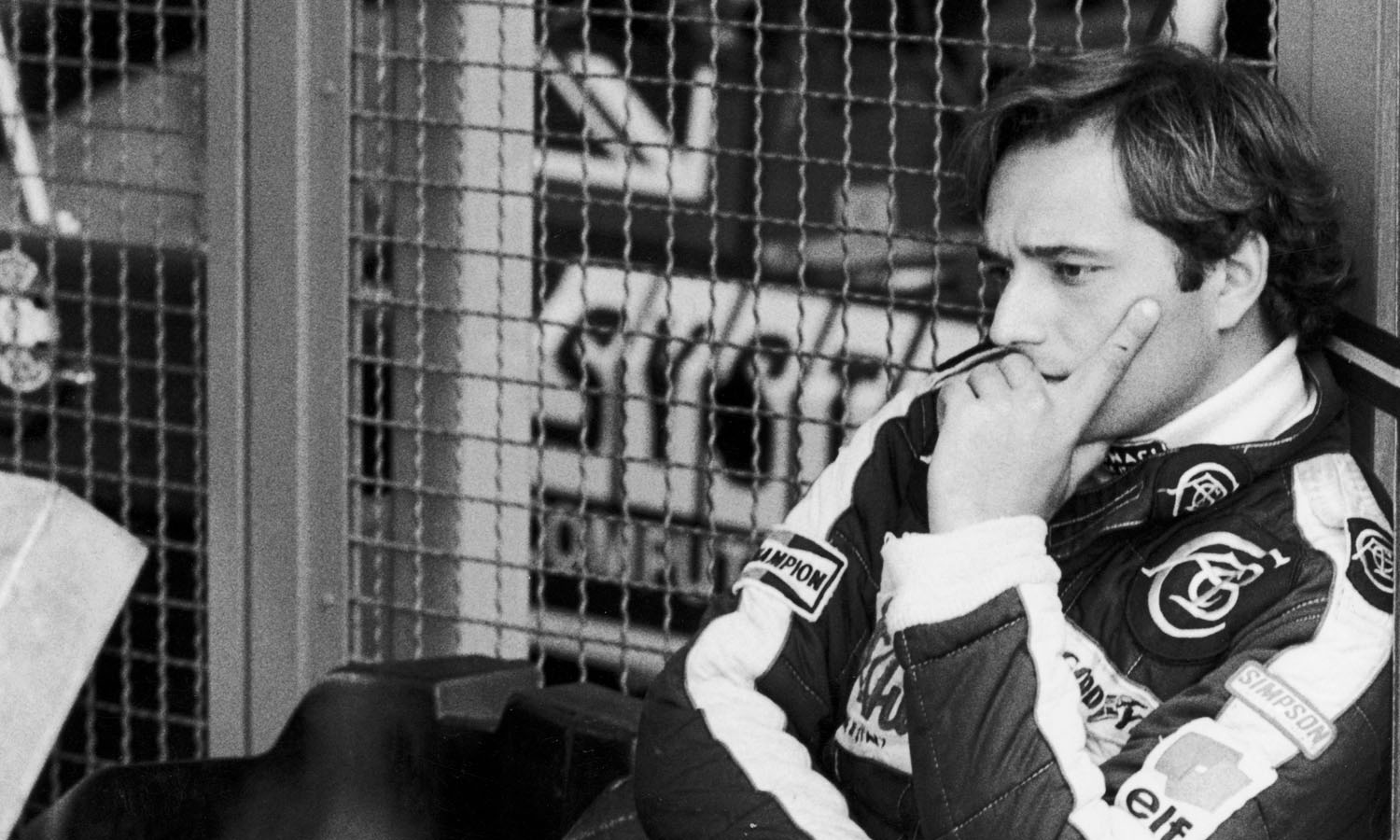

In short, I was constantly complaining, and the enthusiasm was soon to die down. I was afraid that my career would vanish in smoke.

There was this option for F1, fortunately.

At the start of the season I did a few tests at Fiorano. Especially the T3 when Reutemann and Villeneuve were in South America. My best time at that time was 1’10”4 with control tires, that was a good performance. My situation seemed all the better because that of Villeneuve was not immune to all criticism. Then things got better for him. I didn’t want to sink into oblivion, that’s why I decided to do Monaco F3. My victory in this race immediately paid off. It changed the whole atmosphere around me. Forghieri said to me, “You will continue testing with us”.

I had contact with Surtees, but he preferred that I focus on the Ferrari testings. He made me see the uncertainty of the future for Surtees. I also had contact with other teams, Brabham in particular.

At Ferrari nothing seemed to be taking shape in my favor. I wanted to get to the bottom of it. I asked: “Should I consider myself a Ferrari driver or not?” I was ready for anything, even testing berlinettas at Fiorano, while waiting to have an F1 car. Of course, it was a risk because I was told that I was free to make any decisions about my activities in F1.

I had hit rock bottom. The F2 adventure with the Dino engine was doomed to failure. I decided to go to England. All the Italian press was against me, I spoke little English, the situation was not comfortable. I finished the season as part of the I.C.I team with Daly. In August, at Enna, I was beaten in the tests by the Chevron-Ferrari, then driven by Guerra. They said of me, “He’s over. He has an F2 capable of winning and he is slower than the Ferrari”.

After the race, these critics died down, I was ranked 5th. At Misano I was 7th fastest, while the Ferrari did not qualify. I was rehabilitated but nevertheless it was the most difficult period of my career. I raced in Aurora with the Chevron-I.C.I ranking 3rd among the F1s. It was then, in September, that Shadow had me test at Silverstone. Regazzoni had managed 1’18”8. The same day, with the same car, I did 1’17”9. Don Nichols was thrilled and, in Italy, Autosprint talked a lot about this performance. Shadow immediately wanted me to sign a contract for 1979. But I had contacts with Brabham. On the other hand, I took advice from Stewart, who helped me by telling Ken Tyrrell about me. Ecclestone thought I wasn’t experienced enough, so I phoned Tyrrell from his office. Ken has agreed to see me.

Things were speeding up.

Tremendously. I had a two-and-a-half-hour conversation with Ken. He first calmly listened to the story of my career, before saying “I would like to have you racing in Canada with a 3rd car, but you have to sign a three-year contract”.

License

Surprised, I almost fell out of my chair. When I arrived at his house, I was nothing, and he offered me a steering wheel! But he did not want an immediate response. He had me read Pironi’s contract. It was a Friday. He told me that he was preparing the same contract for me and to come back on Monday. My decision was already made. On the scheduled day, I rushed to his house, he made me read the contract, the figures were well paid too! Forty thousand pounds for the first season… We signed, he opened a bottle of champagne, predicting “In 1981, we will be world champions!”

It was delirium! I thought I was dreaming, Ken continued to speak: “We will start the first tests with the old model”. A week later, the first disappointment: “The car will not be available in Canada, we have no spares”.

I wasn’t worried, there were still the tests. After the races in North America, I went to England to reconnect. This is where the real difficulties surfaced. Ken Tyrrell told us the F1 license regulations were going to change. “I’ve got the license”, I told him, but he didn’t believe that. He said, “I’m afraid I would like to be sure of that”. And I insisted, “I will get it. No problem. I’m sure”.

He suspected something. He asked me for my exact record in F3, the precise list. I requested it from the C.S.I, but no one was able to really determine the races that counted for obtaining the international license. I proposed the confirmation of the president of the C.S.A.I, he placed me at the head of the Italians for obtaining this license. But Ken Tyrrell ends up saying: “I can’t wait”.

And when I got back home, in Rome, he had already sent a telex: “I can’t take any risks, I’m releasing you from your contract. I am sorry”.

In short, he let me down. I appealed to a lawyer, brandished threats, to finally accept it was better to draw a line. I found myself in a situation I had experienced before. I got in touch with Shadow again. They had signed with Ongais, but he had his races in Indianapolis and could only compete in eight Grands Prix. They suggested that I find a sponsor for two hundred thousand dollars, because they had no financial support. Nobody was willing to pay me such a sum quickly. A year earlier, I was a professional and now I had to pay. I was hurt to have to appeal to my father. Eventually he advanced me the money which I have since returned to him.

The season was to turn out relatively better than de Angelis feared as Ongais eventually chose to focus all his efforts on American racing. De Angelis had the Shadow at his disposal throughout the season. For his debut, he was excellent in Argentina.

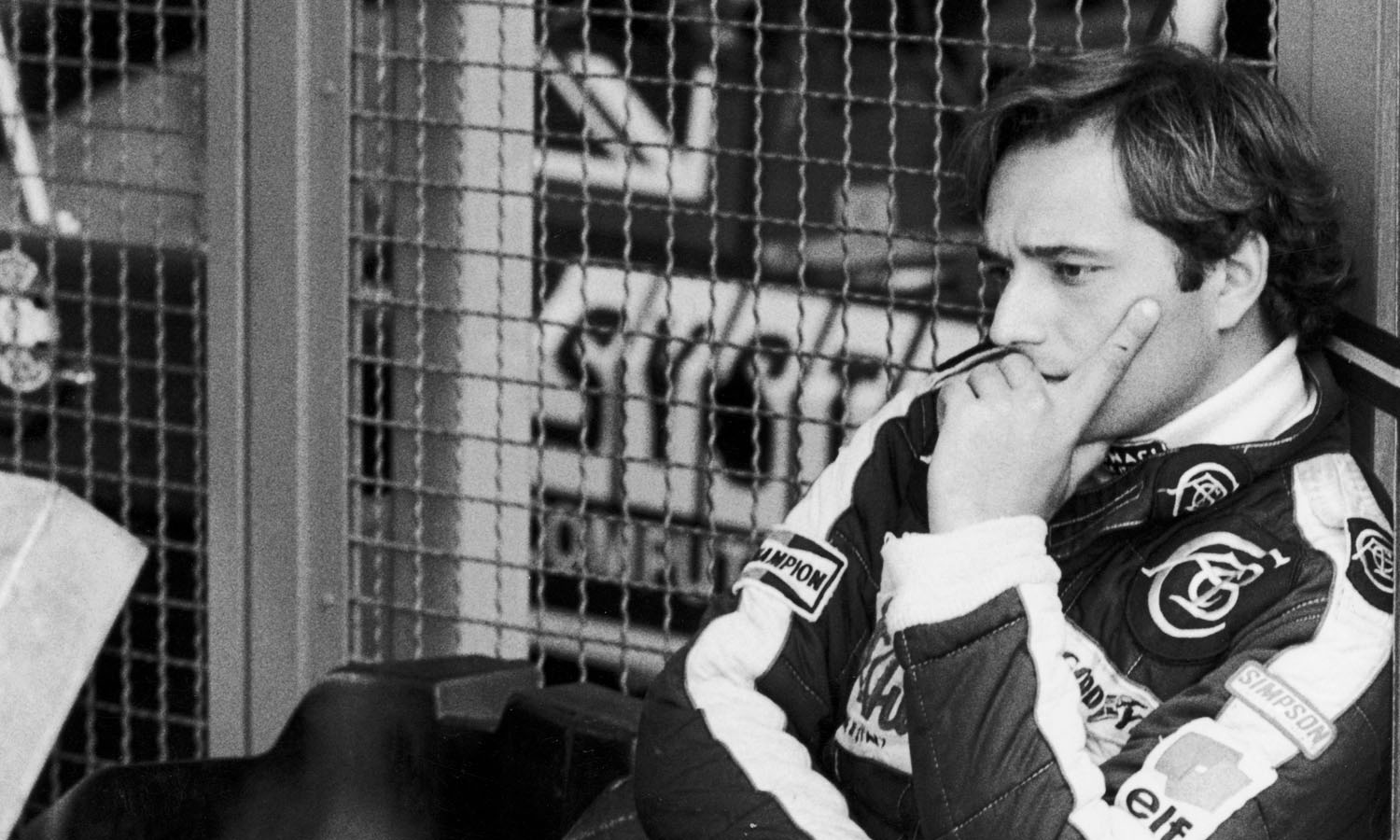

“F1”, he says, “didn’t surprise me. I was expecting the difficulties that I encountered. It’s very professional and getting the car to the finish in a good position is not easy. I had to learn everything about driving, overtaking, saving mechanics”.

One of his greatest personal satisfactions, more than his 5th place at Watkins Glen, is the British GP: “I managed the 12th fastest time in practice, ahead of Villeneuve”, he explains. “We had new rear suspension. This is the day when the Shadow worked best. In the race I was penalized for starting early but I passed guys like Scheckter, Reutemann and Villeneuve”.

He says this without boasting, without implying anything other than the facts themselves. He is a confident boy. Solid, intelligent, well made of his person, he is tailor-made to one day become the idol of the tifosi.

If, in Rome, on March 26, 1958, a fairy leaned over the cradle of a newborn, it can only be his!

© 1979 Sport Auto • By Johnny Rives • Published here for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended.