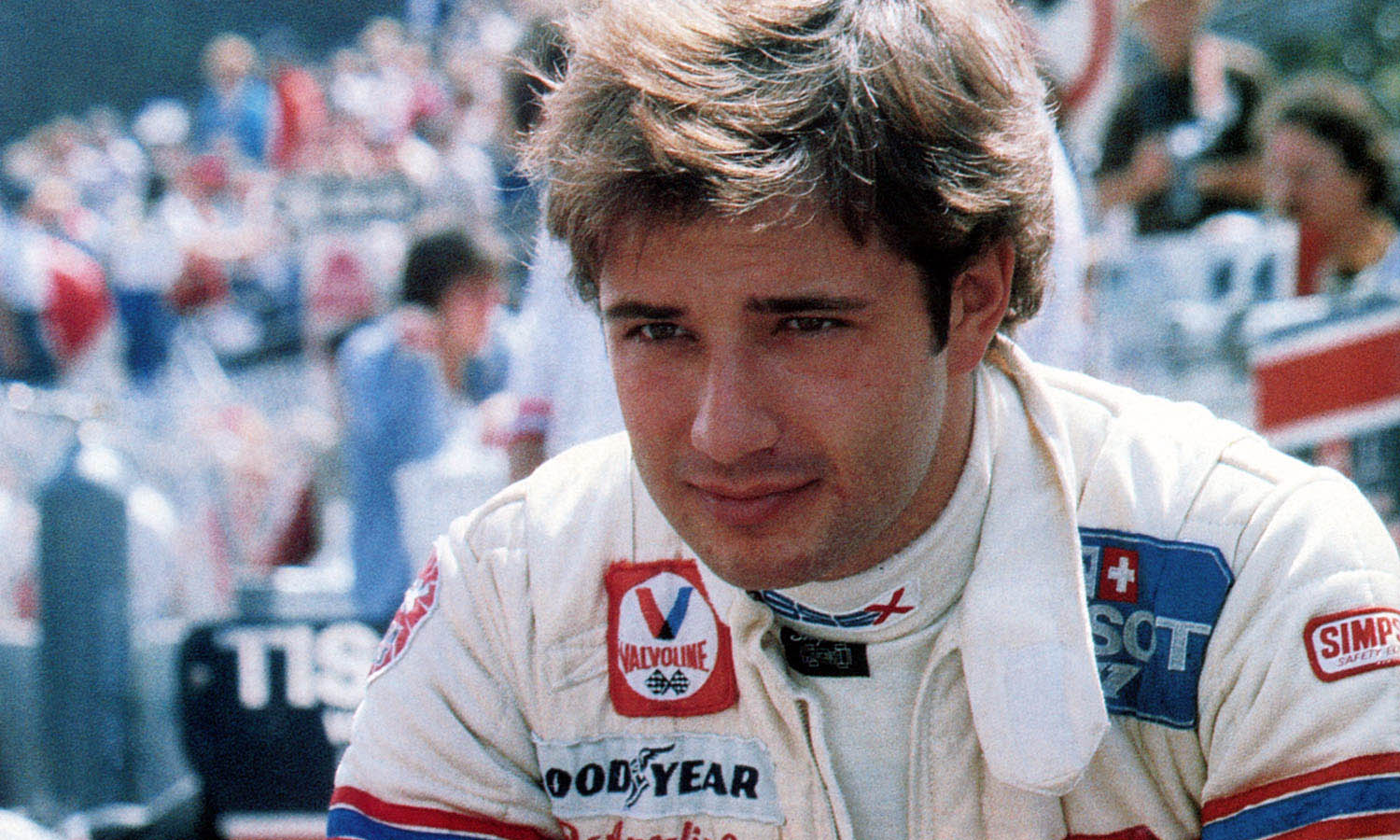

He lives in a villa situated on one of the Roman hills, together with his father, his brothers and sister, and a few servants. Every morning he gets into his tracksuit and goes running to keep fit. Then he showers, has lunch, and dedicates the afternoons to reading and music. In the evenings he gets together with his friends, at times staying up until the early hours.

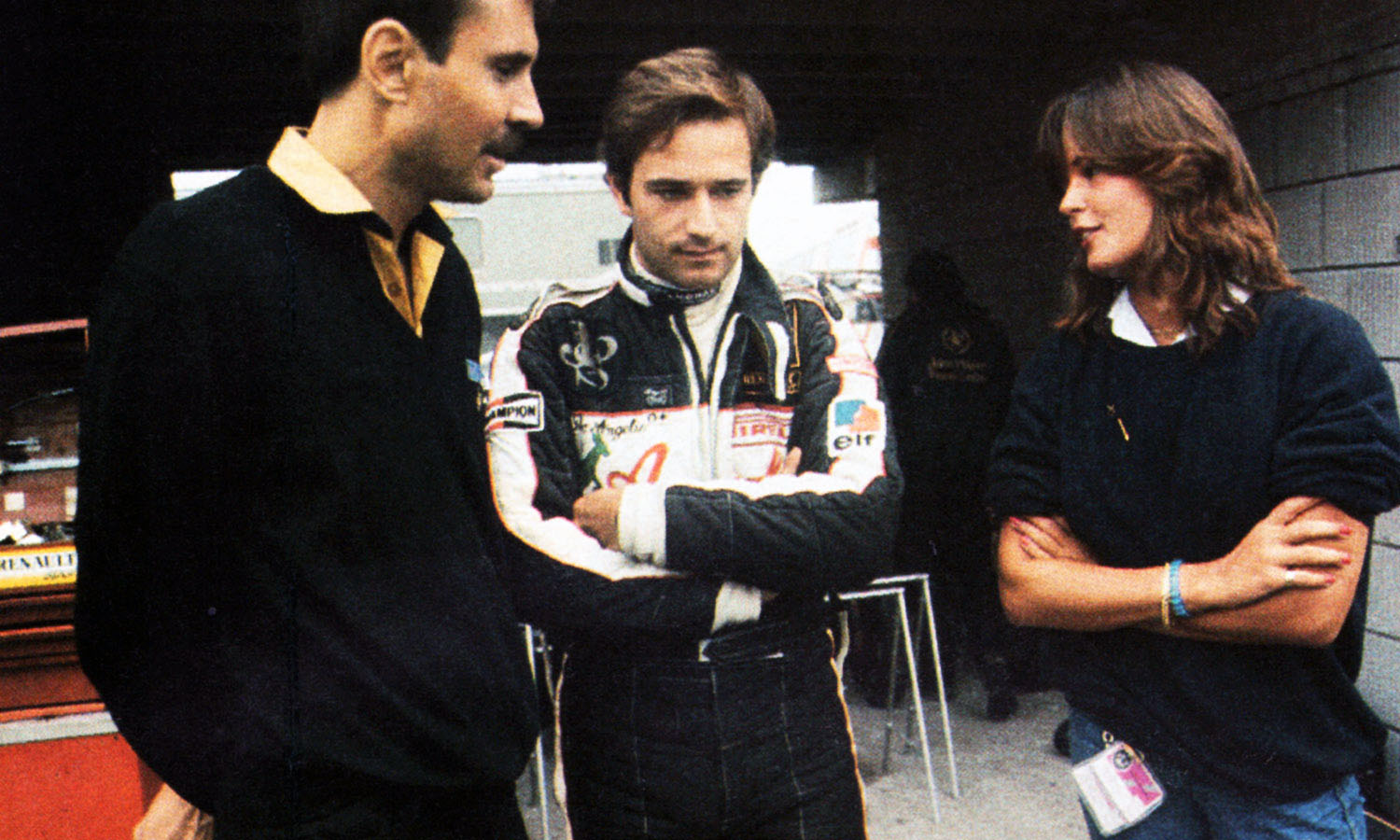

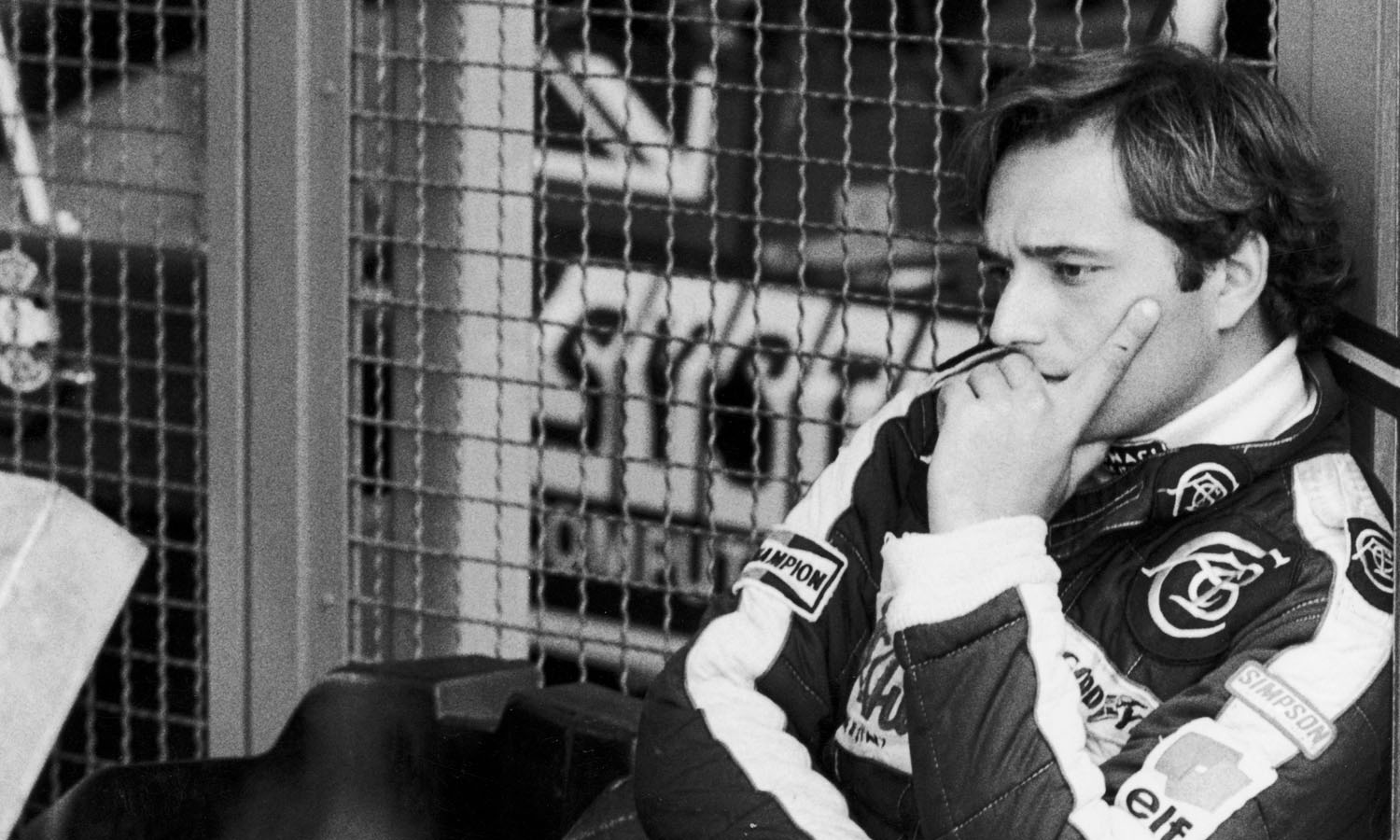

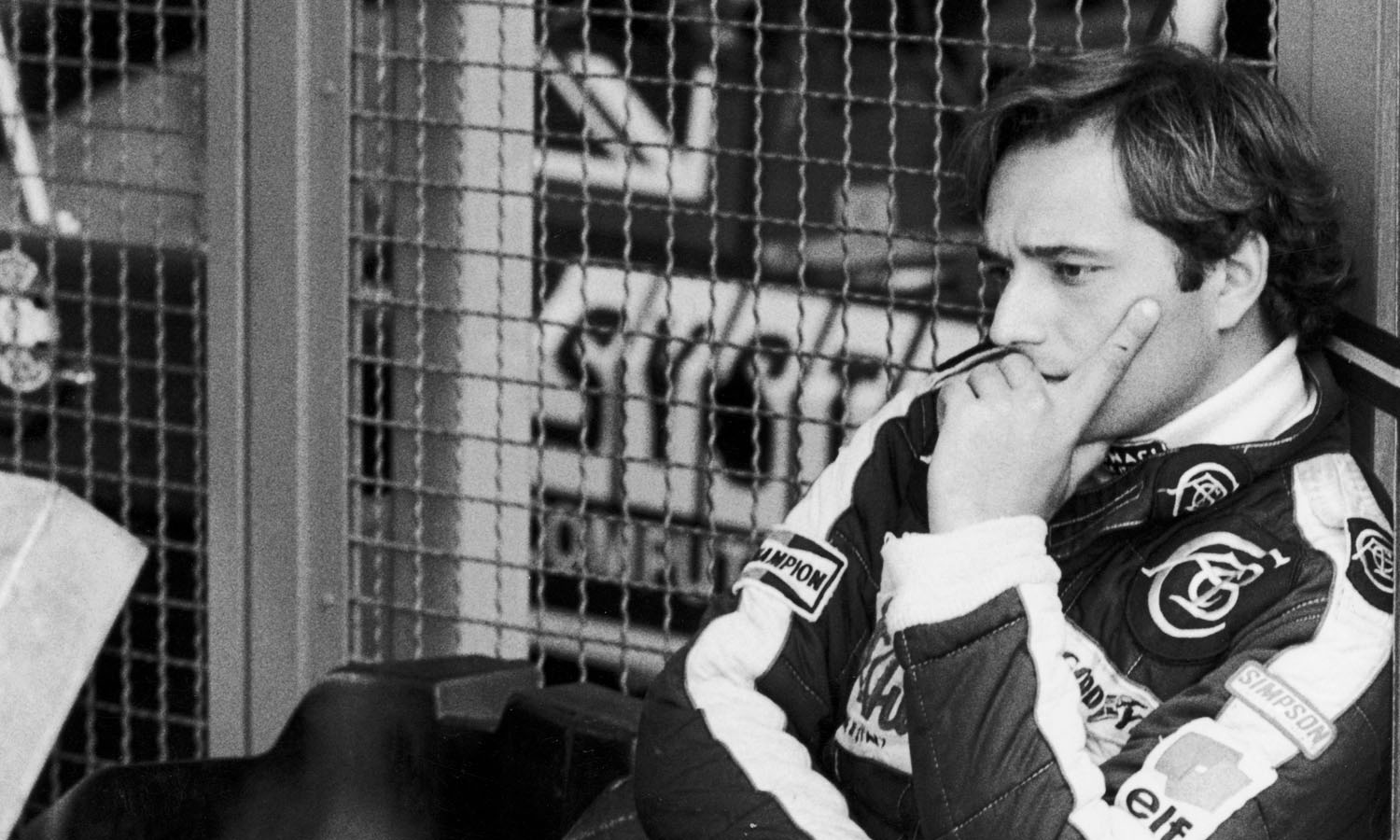

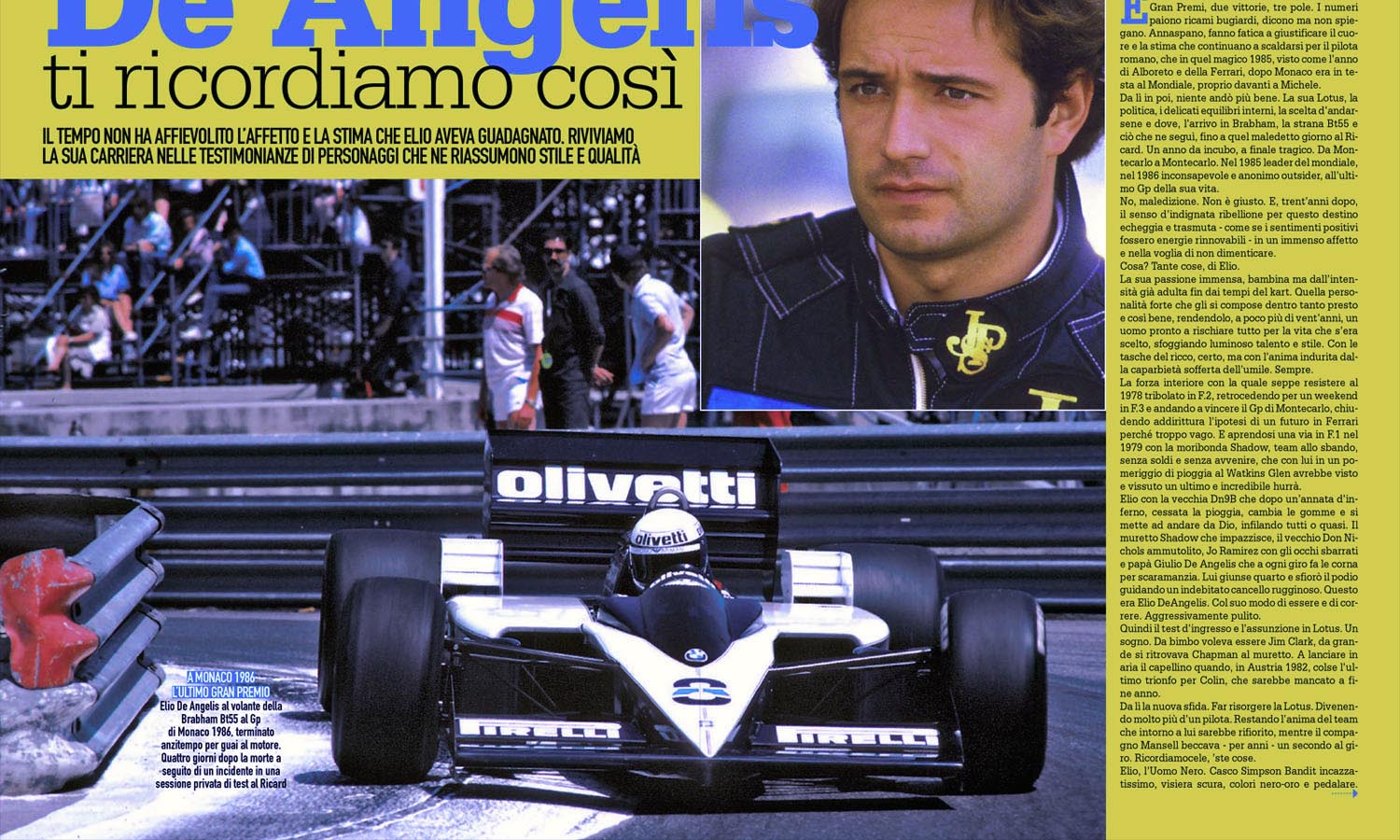

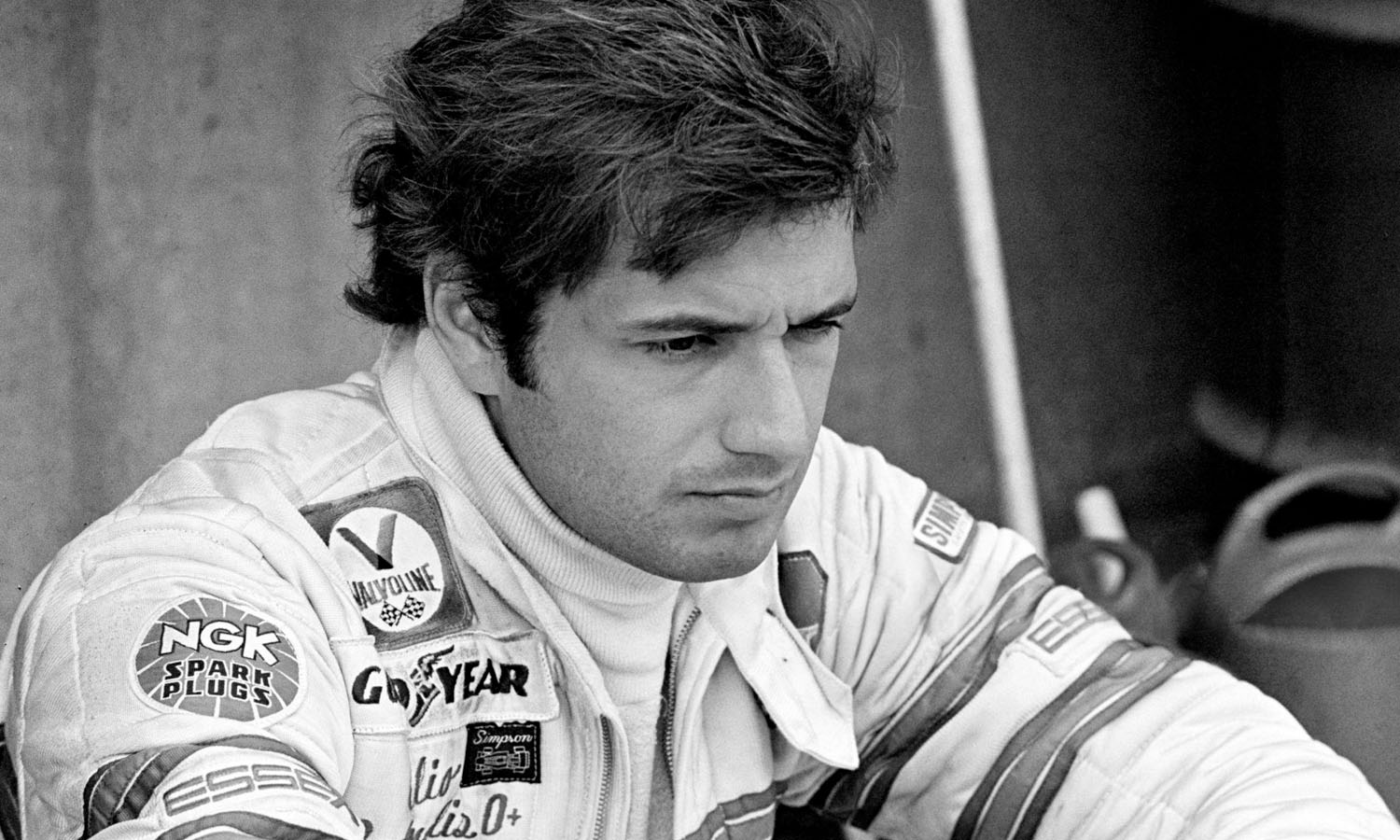

At 24 years of age, Elio de Angelis has already clocked up 57 Grands Prix, culminating in a victory, this August, at Zeltweg. Yet during the winter he leads a very quiet, anonymous kind of life. Every now and then, he takes a trip to Germany where his girlfriend lives, or does a few tests with Lotus. He is not usually to be seen at prizegiving ceremonies, receptions or similar public occasions, being a very private kind of individual. So much so that people have accused him of being downright anti-social. Introverted or reserved might be apter descriptions, although occasionally he does open up and talk freely, almost as though he were letting off steam rather than describing himself.

He must have had quite a few hang-ups in the past. His colleagues have all at some time or other held his father’s wealth against him. He would arouse envy when he arrived at races aboard a private plane, along with his father and the rest of his family, while their pilot waited behind for the race to end, in order to take them all home again. Whenever the de Angelis clan – who would get together in the evenings around the dining table with a bottle of champagne – chose to appear, pretty girls were never in short supply, and that proved to be a further reason for envy.

Even an apparently tolerant and open minded setup life Formula 1 abounds with bitchiness. Elio de Angelis immediately found himself isolated from the crowd when he had reached the top. Although many welcomed his success, sarcasm and envy were rife.

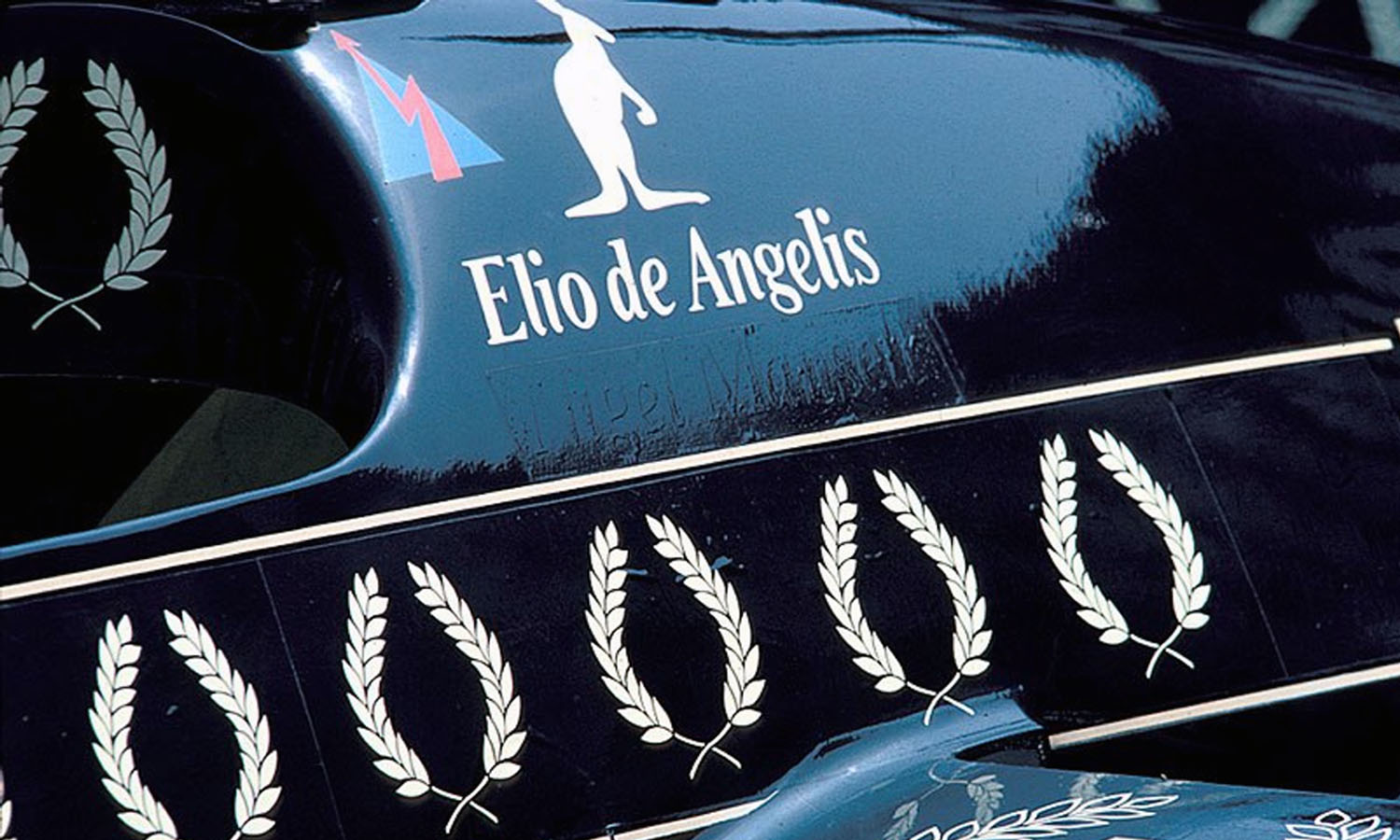

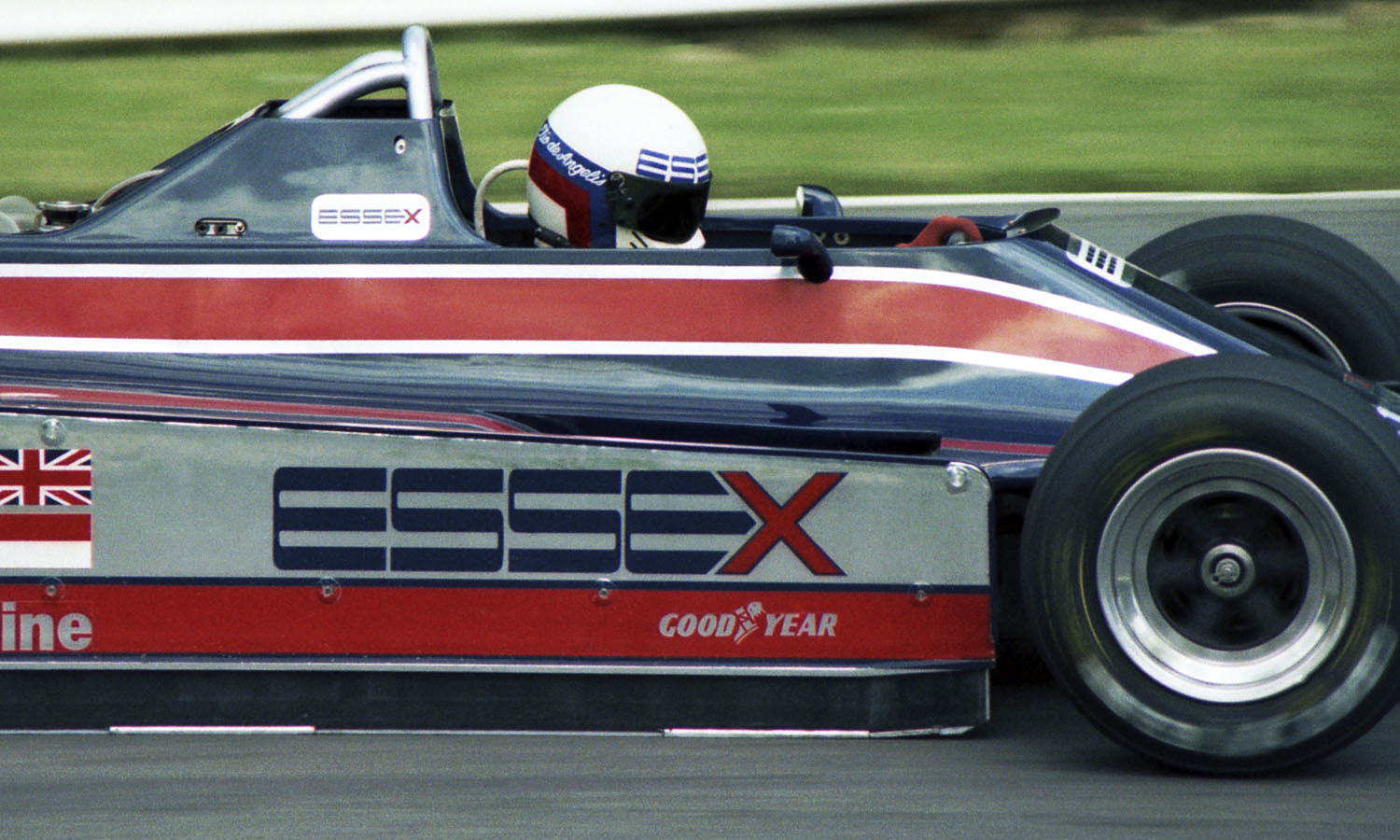

The early results, such as the fourth place obtained in torrential rain at Watkins Glen in 1979, were to shift de Angelis’ name from the gossip columns to the sports pages. The subsequent transfer to Lotus, accompanied by a ‘dowry’ amounting to several hundred thousand pounds, helped make him the epitome of the so-called ‘suitcase pilot’, always ready to move to make the best deal. It was his loyal and sincere team-mate, Mario Andretti, who put this back in their true perspective: “Elio may well be rich,” Andretti said at the beginning of the 1980 season, “but do not dismiss him lightly. Just watch out. He’s good, and very soon he’ll be among the best”. Andretti is seldom wrong in his judgements. Although to some the victory de Angelis obtained at the Austrian Grand Prix may have come as a surprise, to many others, who had changed their minds about his merits, it merely came as a confirmation of their new opinion.

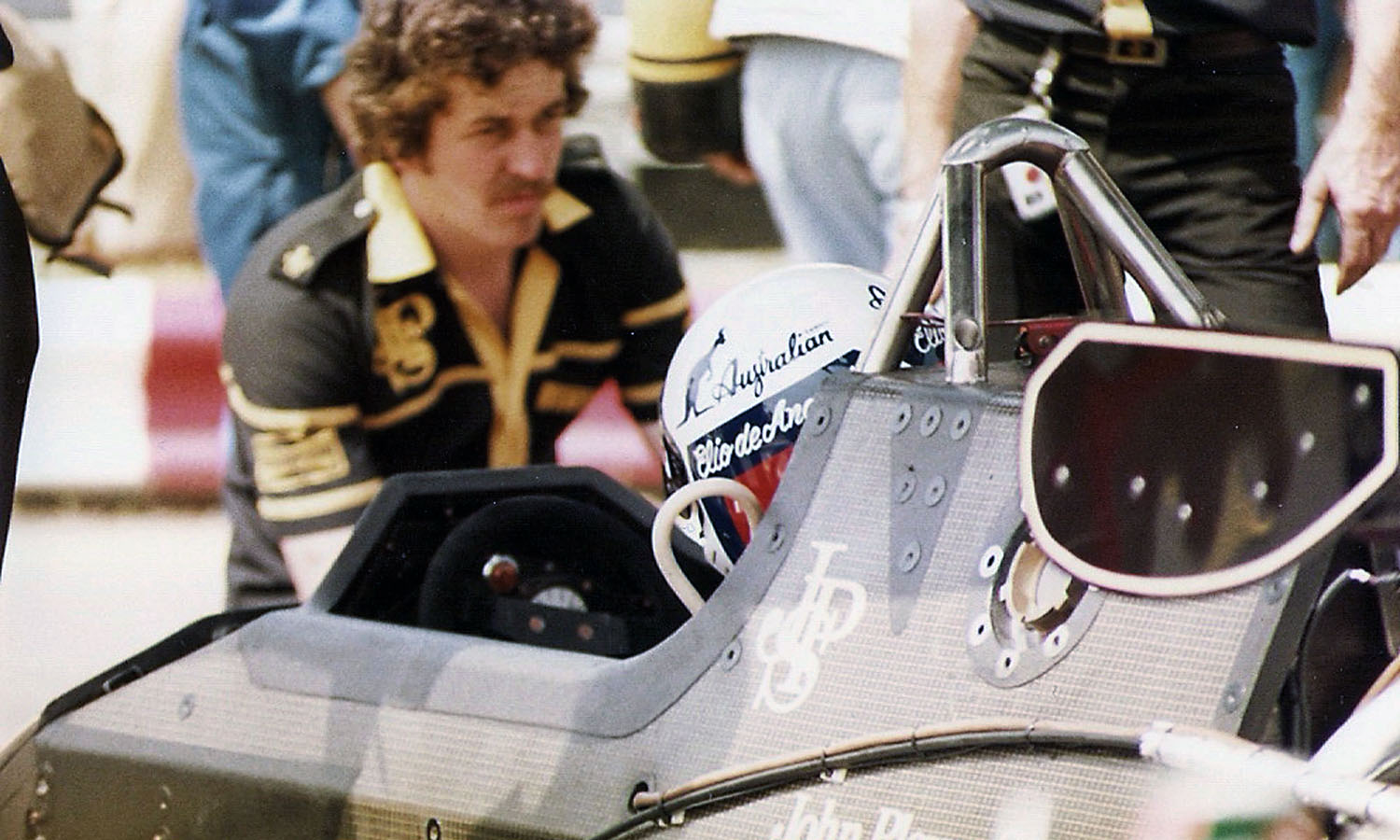

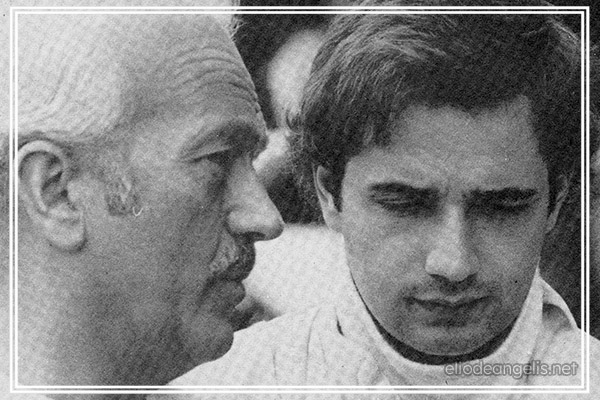

Most people had forgotten that de Angelis, when he was merely 20, had already tested the Ferrari T3 cars of Villeneuve and Reutemann. However, this collaboration with Maranello was to last for the lengthy duration of the tests. Ferrari already had an eye on Scheckter for 1979. Young de Angelis, although considered promising, would have been too much of an unknown quantity. What was more, as far as Enzo Ferrari was concerned, de Angelis has further drawbacks: being Italian, and a Roman to boot.

“With Ferrari”, de Angelis explains “I had an option which wasn’t honoured. Still, not that I ever cherished any illusions on that account. I wanted to race in Formula 1 right from the start, but they weren’t able to offer me anything, and that’s how I wound up with Shadow, a second level team, which nevertheless proved a useful experience for me in that it enabled me to understand the set-up and the men. Now I am able to see Ferrari in a totally different light. A spell with them is important, though by no means vital if you want to win a Formula 1 Grand Prix”.

“Obviously I’d like to be in Arnoux’s or Tambay’s place. At Misano I envied the applause given to Rene simply because of the Ferrari horse emblem on his overall. I couldn’t help wondering how much more this applause might increase if, for example, Patrese and I also raced for Ferrari. These days, however, I consider myself English, from the car point of view, anyway. An Englishman with an Italian heart!”

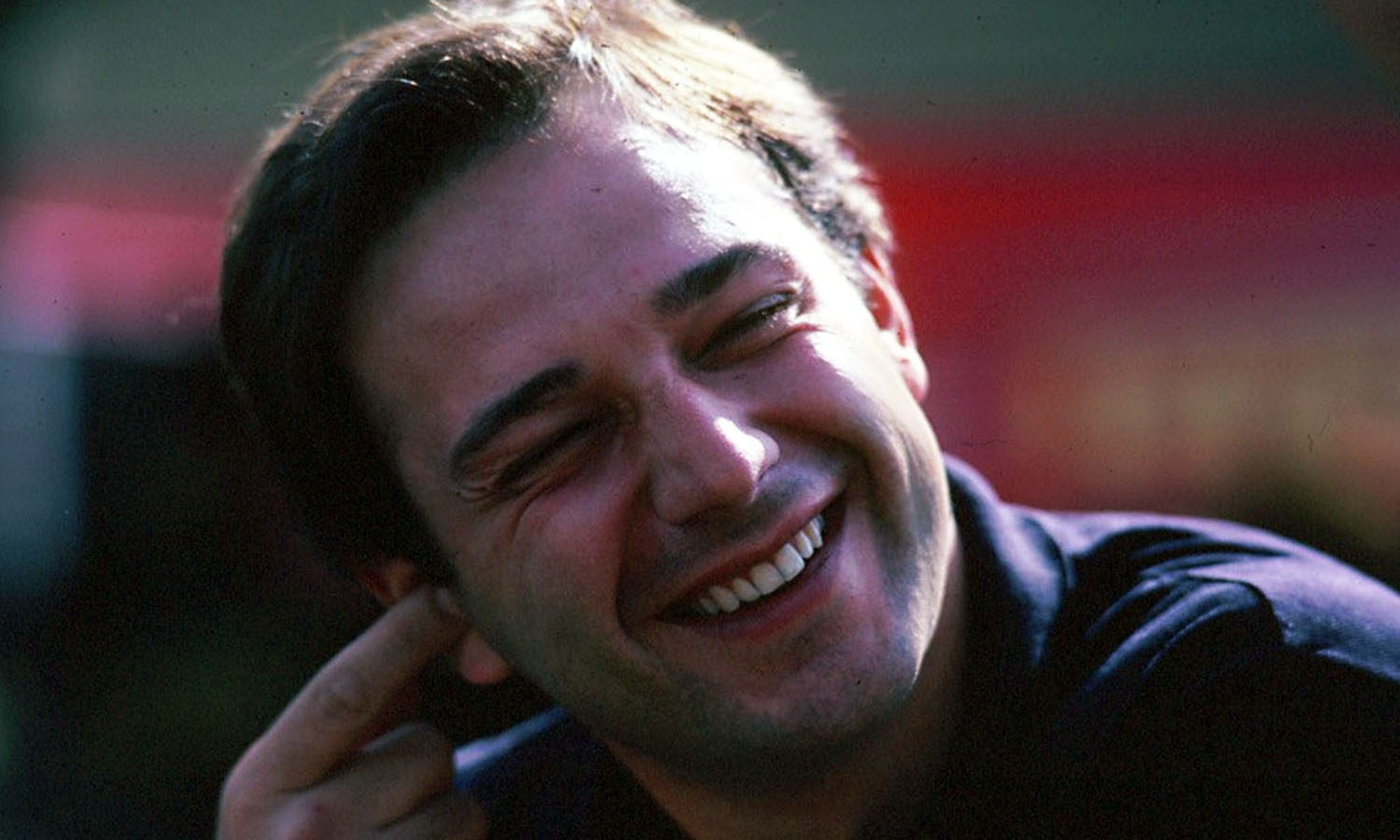

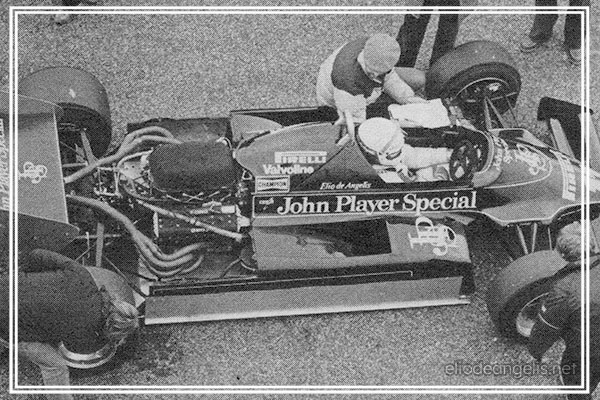

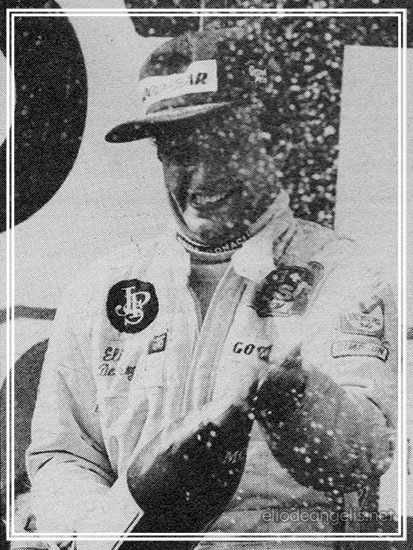

Yet de Angelis has had his share of applause too, even if it seems a long time ago now. At Zeltweg there was jubilation, a veritable apothesis. And those applauding, what is more, were not merely Italian, but also Austrian, German and English. It was a fantastic last lap, with de Angelis beating Keke Rosberg who, six weeks later, was to become World Champion. “It wasn’t until I’d thought about it for a week that I fully realised just what that particular victory meant for me. It was the kind of thing I’d always dreamt of achieving, but more than anything else it proved that I’d made the right choice in life. When you start racing, you never know whether you are going to be good, or whether you are always going to bottom of the group. Although I was confident about my ability, that in itself is a pretty meaningless feeling if you don’t win. My life has changed somewhat since I won: I feel I can afford to rely more on my own judgement.”

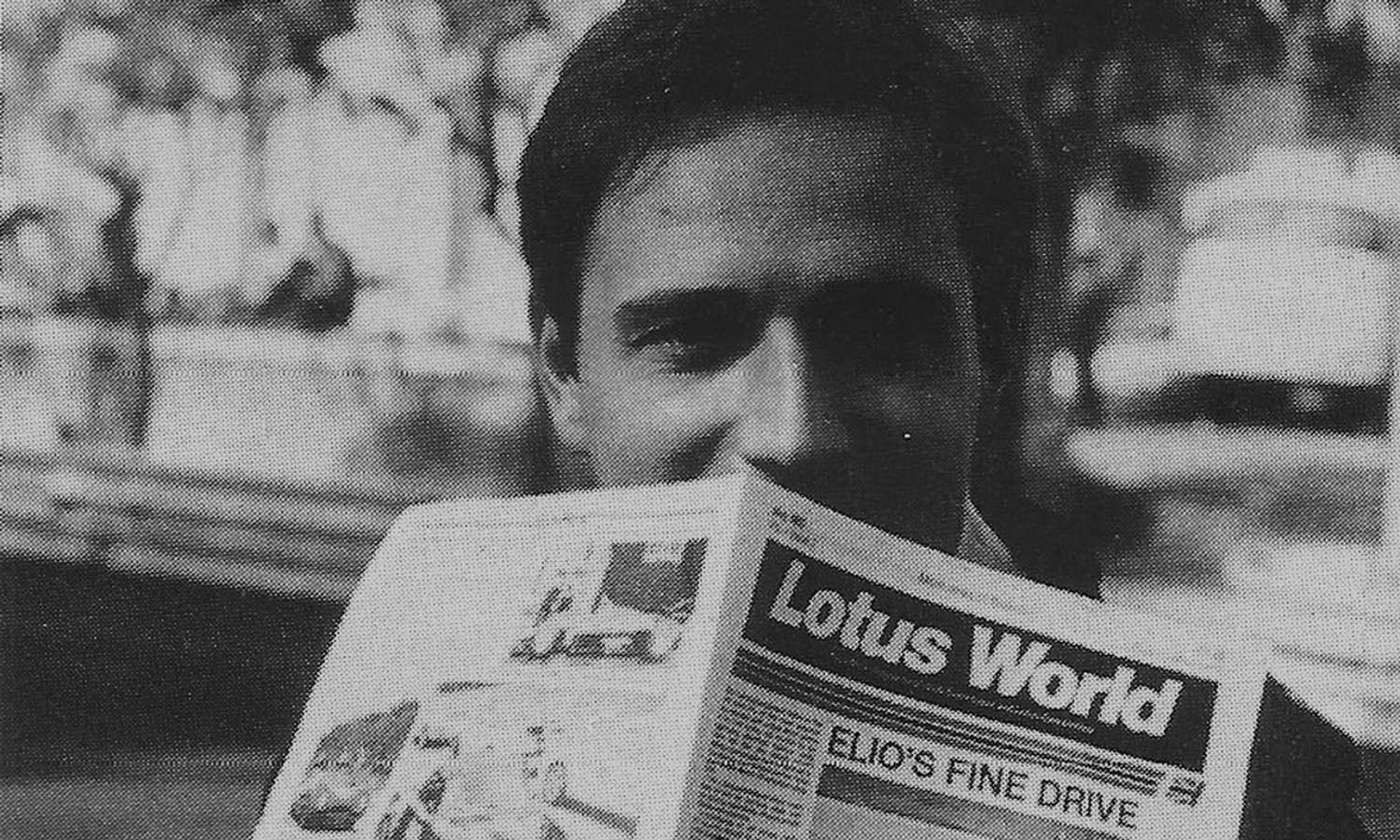

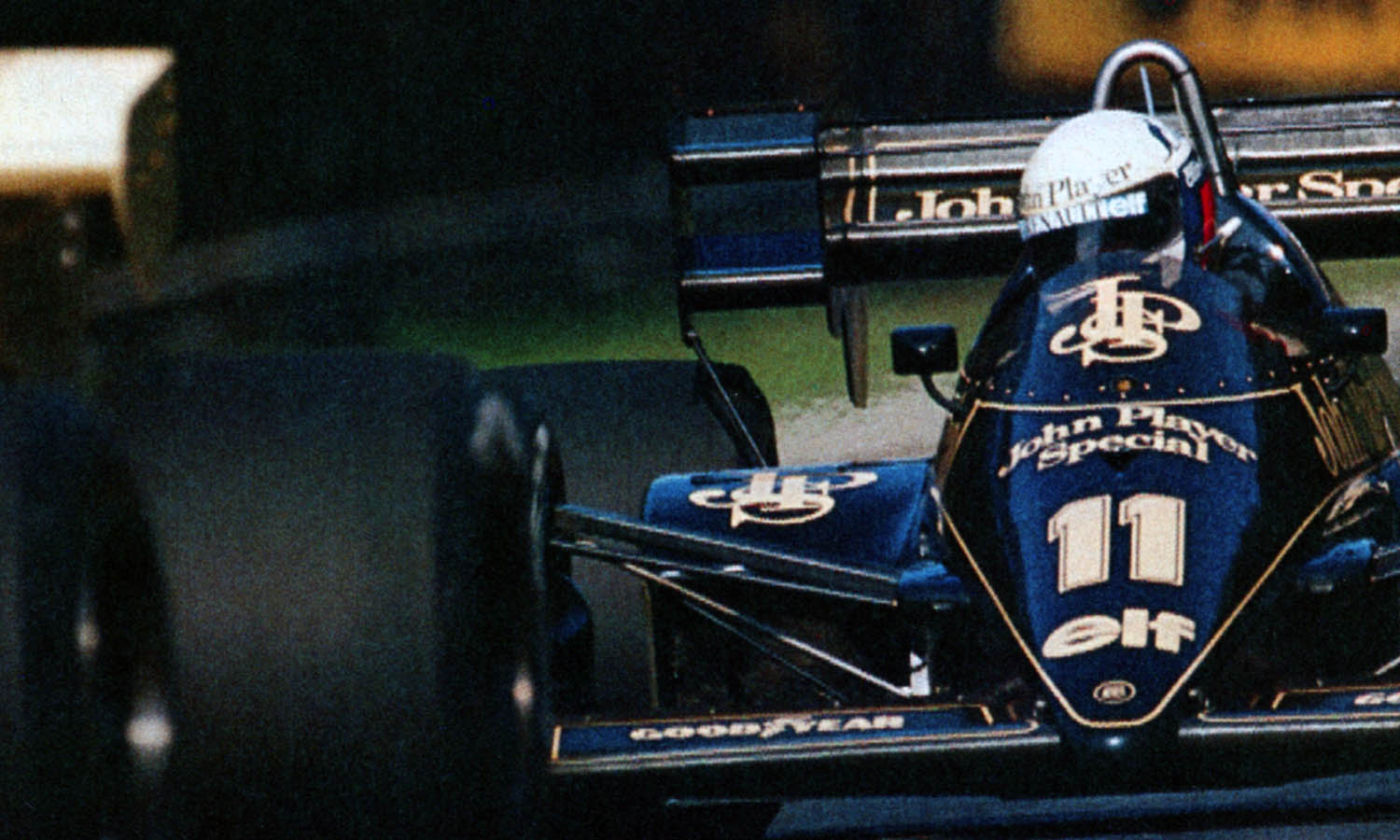

Thanks also to that success, relations with Colin Chapman were able to return to normal. De Angelis already seemed poised to leave Lotus, and that would have suited quite a few people. Williams were prepared to make a big offer to get him out. And he was about to accept, because he couldn’t swallow the fact that Nigel Mansell received more attention in the team than he did. Once, he burst out to us:

“Chapman kept telling me that at Lotus there is no such thing as a ‘number one’, and that he had the utmost confidence in me. Yet at the same time he put two cars on the track with Mansell’s number 12 and only one with my number, despite the fact that development work relies much more on me than on Mansell. I really don’t get it….”

Perhaps Chapman wanted to make de Angelis understand in a roundabout way that they didn’t necessarily owe him anything, and that one has to slog really hard to get to the top. “I slogged a great deal more”, de Angelis explained, “than most people seem to realise. Of course it is true that I was able to start my career with my father’s money; I don’t deny that. Yet the very fact made it all the more important to prove that I could make it because of my own ability. I was underestimated for a very long time. Take Giacomelli – he’s never had any such problems. And his career, which has traced a steady upward curve right up to Formula 1, has always been followed with a good deal of affectionate interest. People are happy about his success. Still, I am quite satisfied with my present situation. I no longer need to rely on my father’s support. I can stand on my own two feet. I earn my own living. And I’m only just 24. How many others of my age could honestly claim the same thing?”

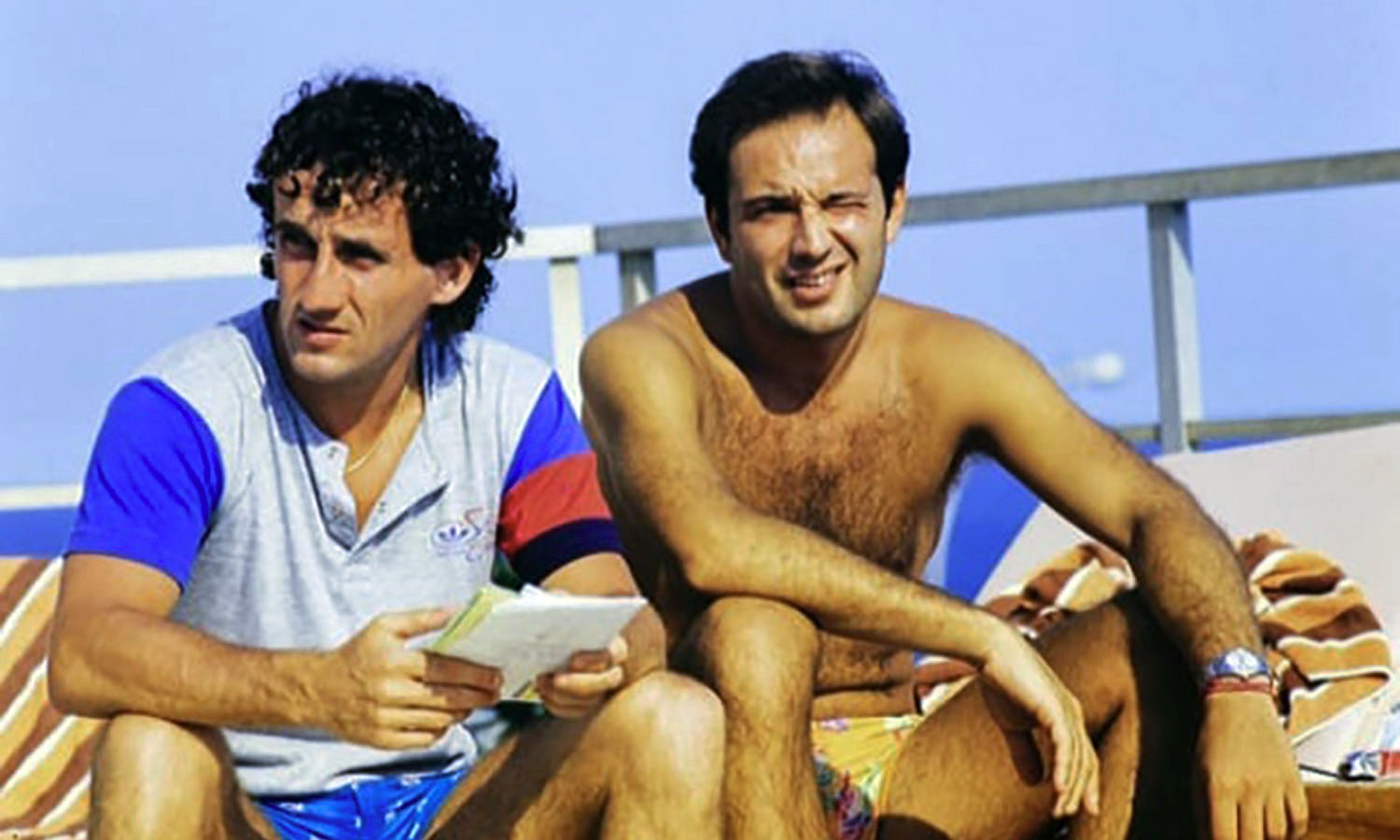

The reference to Giacomelli takes us back to the rivalry between Italian racing drivers: “I’ve never envied the others. If anything, it has quite unjustly been the other way round. What’s the point in saying that you are doing better than Patrese if there are another 10 ahead of him? And, talking of Patrese, there is something he has which I’d like to have too: the conviction of always being the best. And Alboreto? I’d like to be as clever as he is in his dealings with sponsors, with the press and with people in general. “But the two I admire by far the most are Lauda and Rosberg. Niki is consistently excellent, and Keke shares my own romantic vision of racing; he’s not one of those hardened professionals like Cheever, but someone who also knows how to enjoy himself. He smokes, stays up late and drinks if he feels like it.”

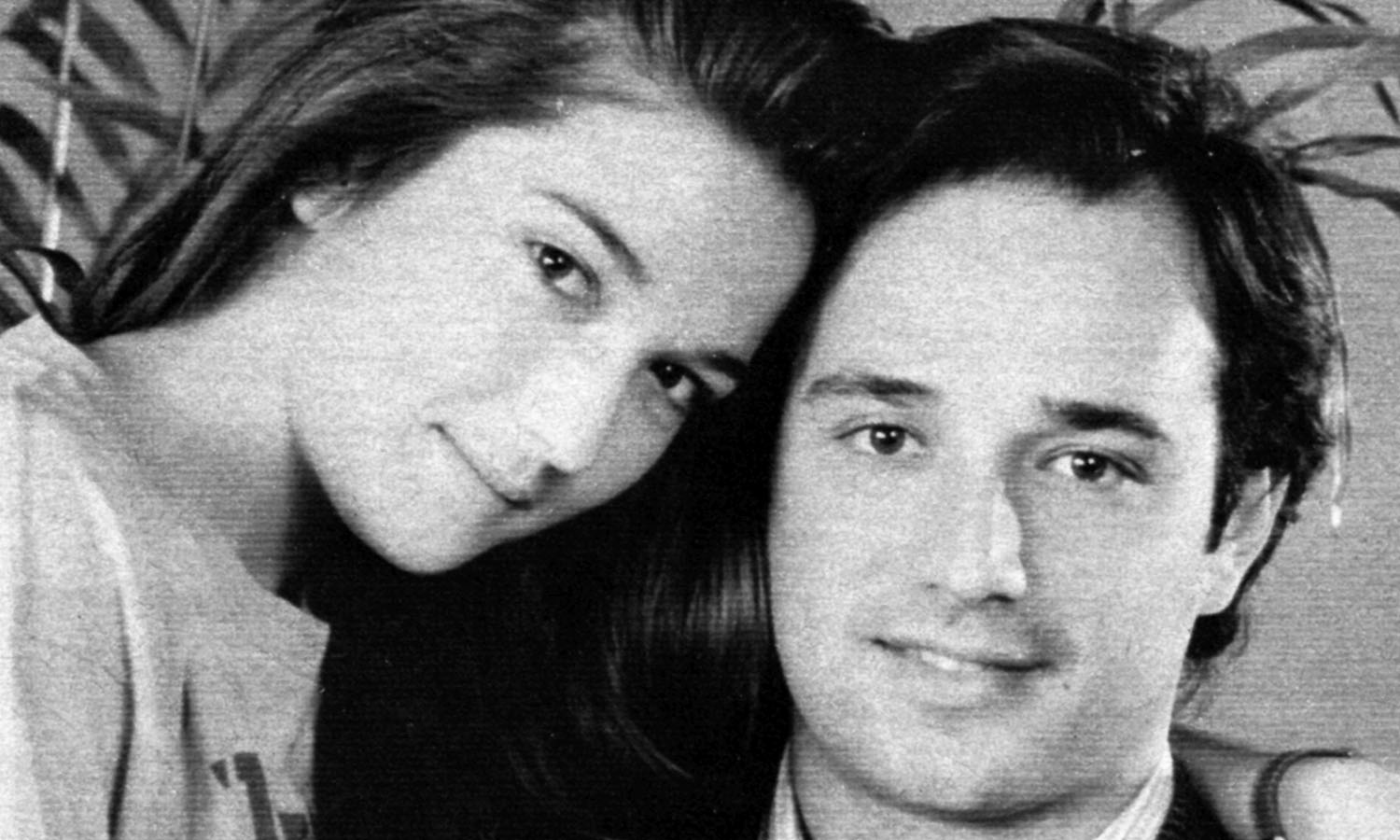

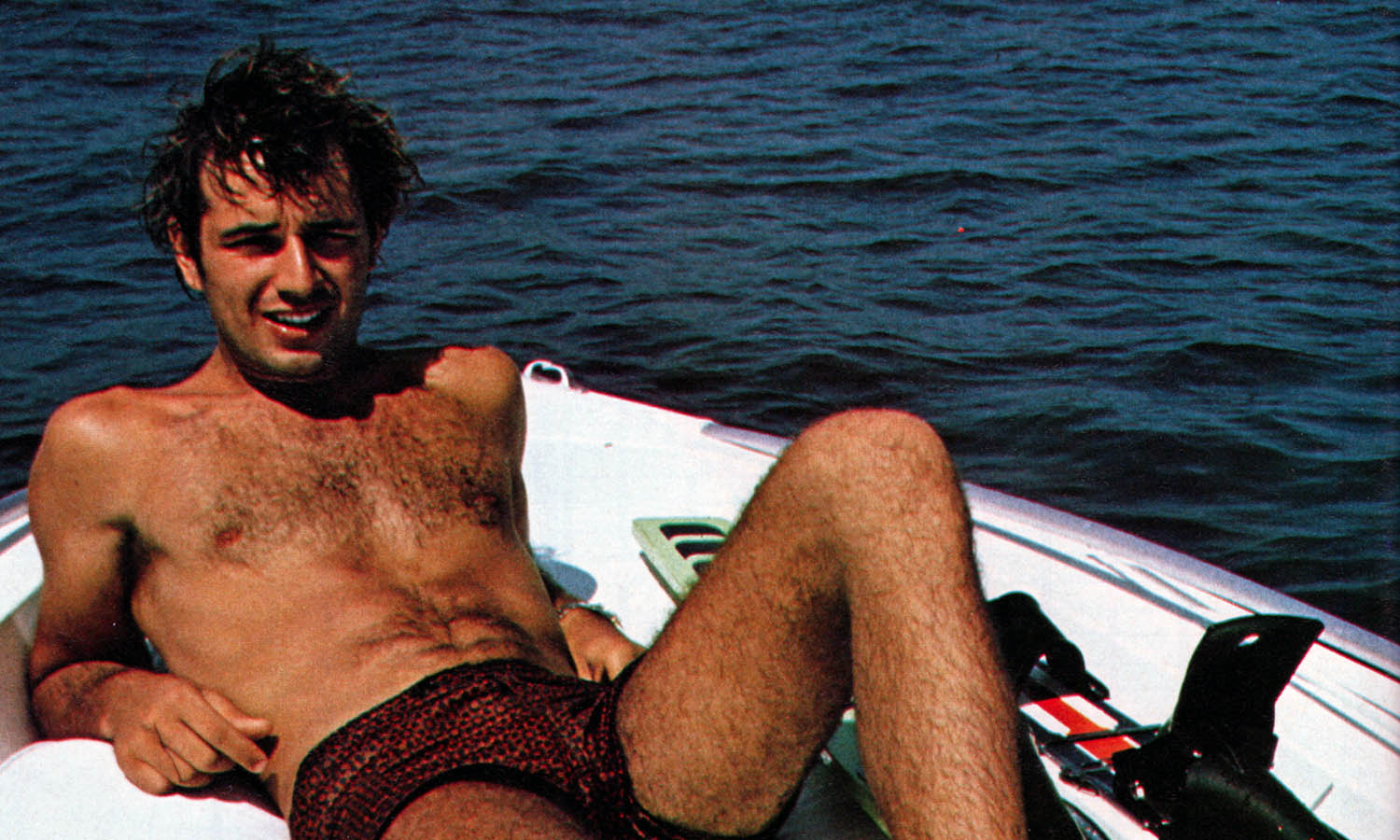

After the Las Vegas Grand Prix which ended the 1982 season, de Angelis went to Palo Alto with Rosberg to celebrate the title which the latter had just won. The he travelled around the USA with his girlfriend, Ute. It happens quite a lot that de Angelis makes good use of work transfers in order to get to know the world a little better. This too is a way of keeping in contact with reality: “Some of my colleagues only live for jogging, tennis and cars, I have other interests. I’m not a bad pianist and I compose music. My favourite singer is Stevie Wonder. Who knows, perhaps some time in the future it could become a profession? And I also love fishing. Whenever I’m in Sardinia, I’m out at sea all the time, and have my own secret spot where I catch fish. Even my brothers don’t know where they are. Formula 1 is a profession which I enjoy, but I don’t intend to stay in it forever. If in my early 30’s I still haven’t won the title, I’ll quit and take up something else.”

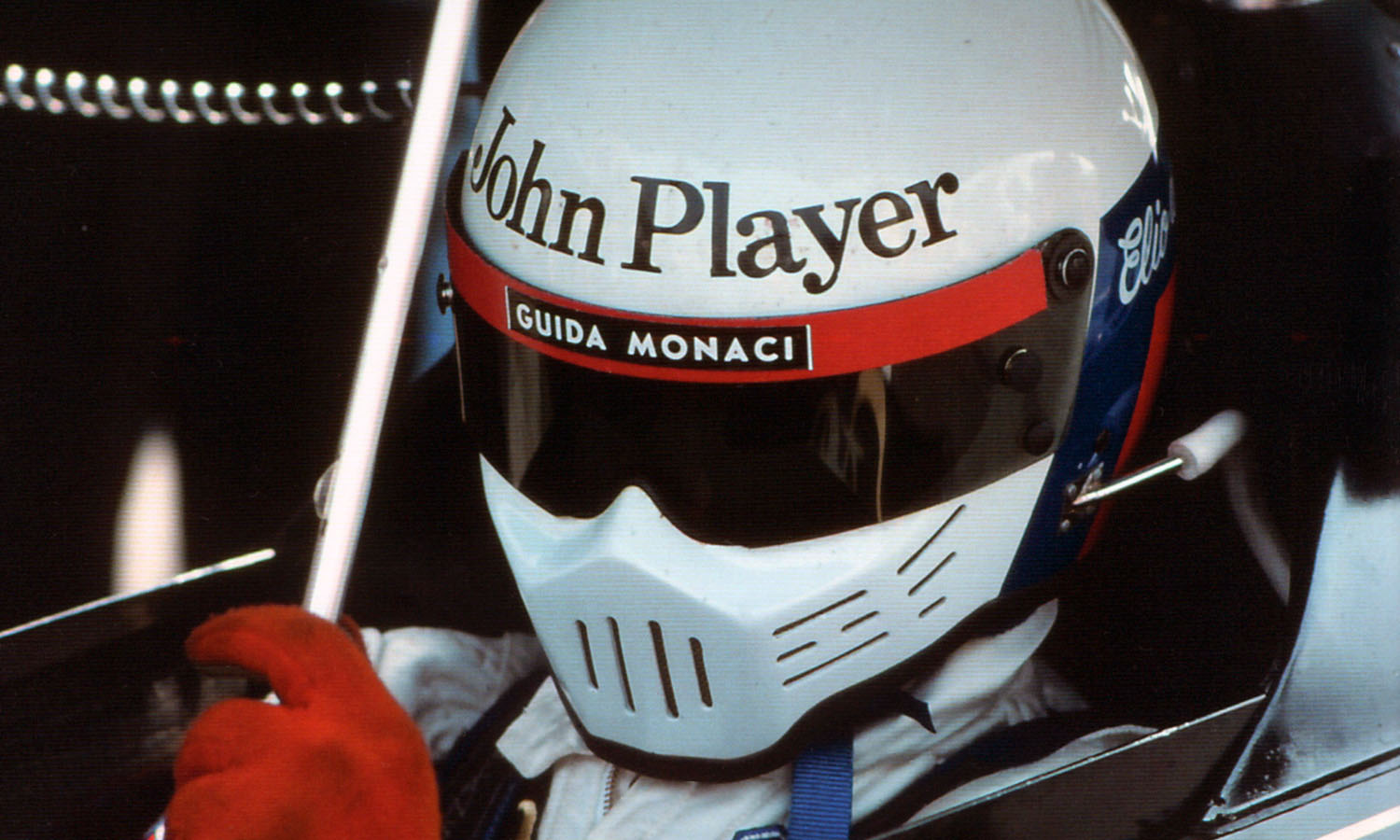

Meanwhile, the 1983 season could bring about a complete change in the present picture, given that certain modifications will be imposed by the new regulations. “As a racing driver, I belong to the ground-effect generation. Since my Formula 3 days I’ve driven cars with skirts, which I personally consider very safe. Although it is only my personal opinion, the new flat-bottom F1 cars seem much more dangerous to me, because of the high speeds they are able to reach on the straight and the diminished downforce corners. I already noticed it at Misano, in a Lotus with a Cosworth engine. This month I shall be trying out the new Lotus with the Renault Turbo engine. The engineers are all optimistic.”

Until then, everybody will be trying with cars which FISA has tried to slow down by abolishing skirts and reducing wings to obtain the same times as those registered with the wing cards. But those who worry most about safety are rarely the drivers themselves: “Racing Drivers”, Elio explains, “nearly always disagree among themselves about anything concerning money and cars. But we do all tend to be rather fatalistic. I got the biggest fright of my life not at the wheel of a racing car, but in the sea, when at Rio de Janeiro I jumped into the water to save Peter Collins, Lotus’s technician, from drowning. The current was so strong that I couldn’t get back. And all the while I could see the police stopping other volunteers from doing anything, fearing that the tragedy might escalate.

Then, by sheer luck, I managed to make it. But every now and then that episode comes back to me and terrorise me. Clearly my number wasn’t up then!”

We mention earlier that de Angelis lives with his family, a close-knit clan consisting of his father Giulio, his two brothers aged 23 and 20, and his 17-year-old sister. For him, the family is of paramount importance in life: “We’ve always been very open and communicative with each other. I used to follow my father when he raced powerboats, and remember that I used to observe him very carefully. It was from him that I learned how to behave after disappointments, then I came to understand the importance of patience. I get on well with my brothers. They are fans who really know the score, because all three of us in fact used to race karts, even though I turned out to be the only one who subsequently pursued a racing career. Marriage? I don’t have any plans. I’m too independent, and every so often I need to be alone, even if I frequently grab the first plane to Frankfurt, to see Ute.”

For Elio, though, 1982 ended on a very sorrowful note: “I was shattered when I heard of Colin Chapman’s death. I owe him so much. Since I joined Lotus, Colin taught me not only how to drive but also how to live. I had absolute trust in him – in fact, I re-signed for Lotus in ’83 only because of Colin. For me, he ‘was’ Lotus.”

“We had our problems when I first went to Lotus, because we didn’t know each other very well. I am basically a very shy person, and I don’t think Colin appreciated this at the beginning. Eventually, though, we understood each other well, and then our relationship was just perfect. I just cannot imagine motor racing without him”.

© 1983 Autosport • By Pino Allievi • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended