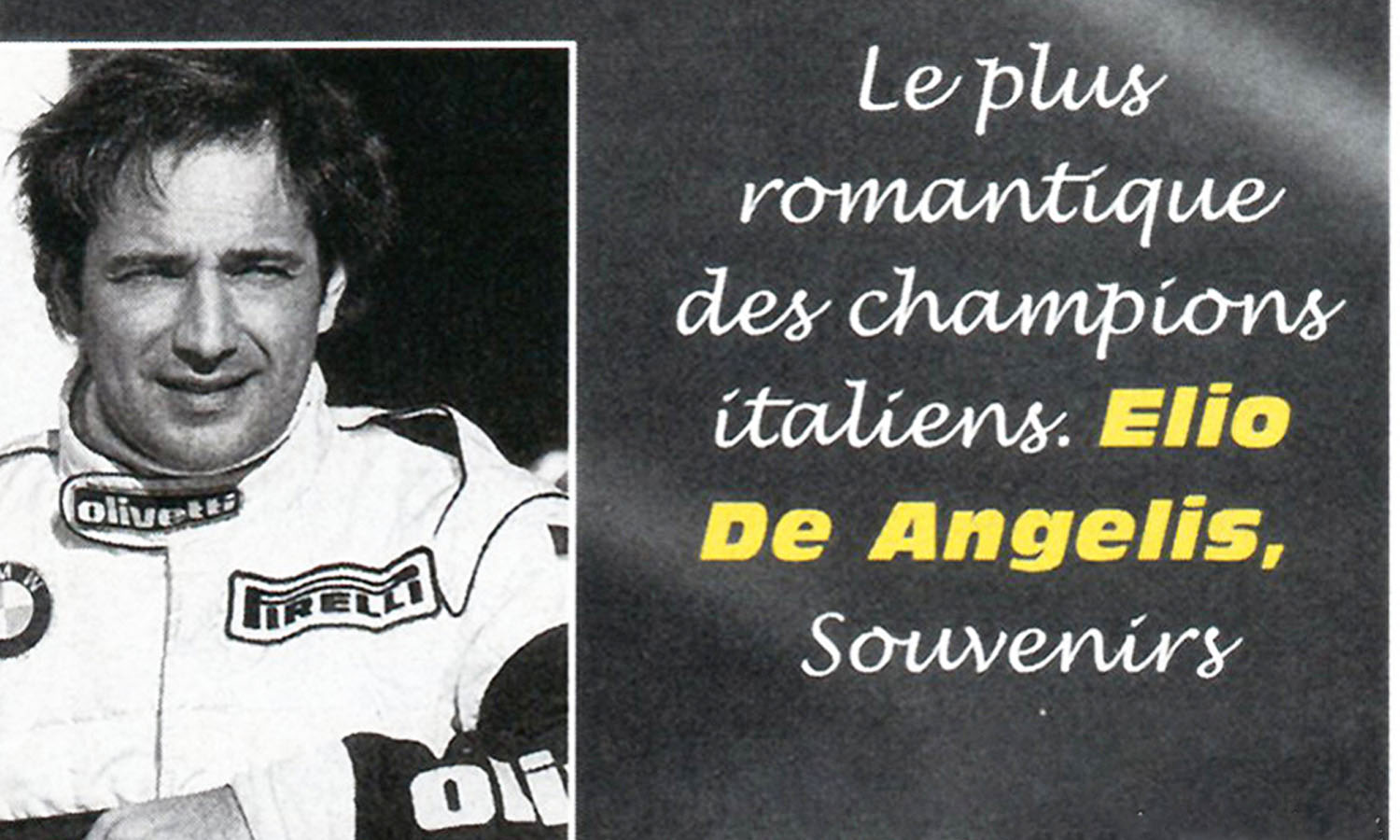

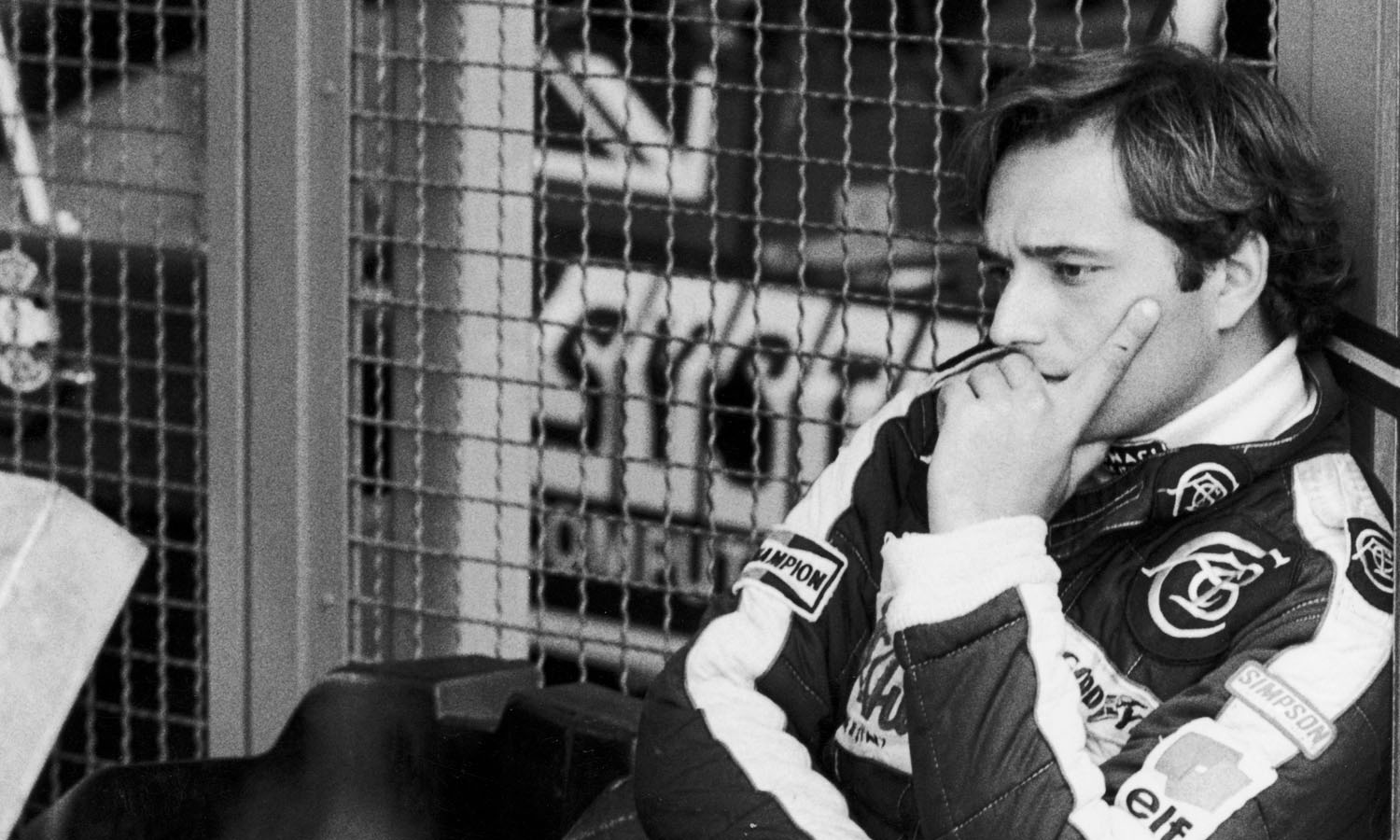

Looking back at the career of Elio de Angelis, the popular Italian who became synonymous with Lotus but was needlessly killed in a testing accident with Brabham 20 years ago.

When Ayrton Senna and Roland Ratzenberger were killed at Imola in the spring of 1994, a dozen years had passed since the previous fatal accident at a grand prix, and many reports suggested that, prior to Imola, Gilles Villeneuve and Riccardo Paletti had been the last Formula One drivers to die at the wheel. Not so, of course. In May 1986 we had lost Elio de Angelis, whose life ended, as with Bruce McLaren 16 years earlier, in a mid-week testing accident.

Three days before, de Angelis had competed in the Monaco GP. His death caused grief and outrage in equal measure. Within the sport he had been the most well-liked of men; it was bad enough he had died in an accident not of his own making.

Worse by far that he need not have died at all, that the attempts to rescue him were pathetic, inept, inexcusable.

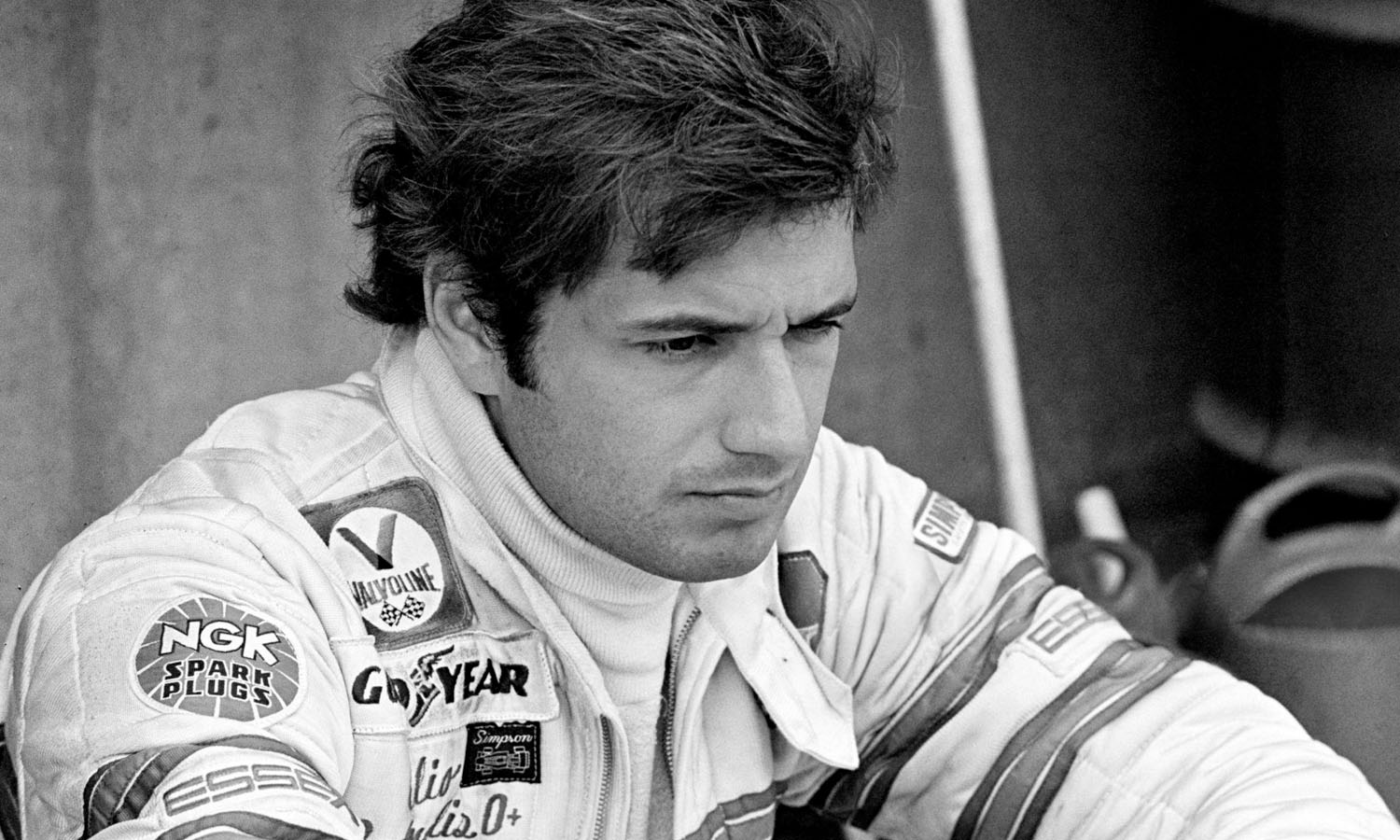

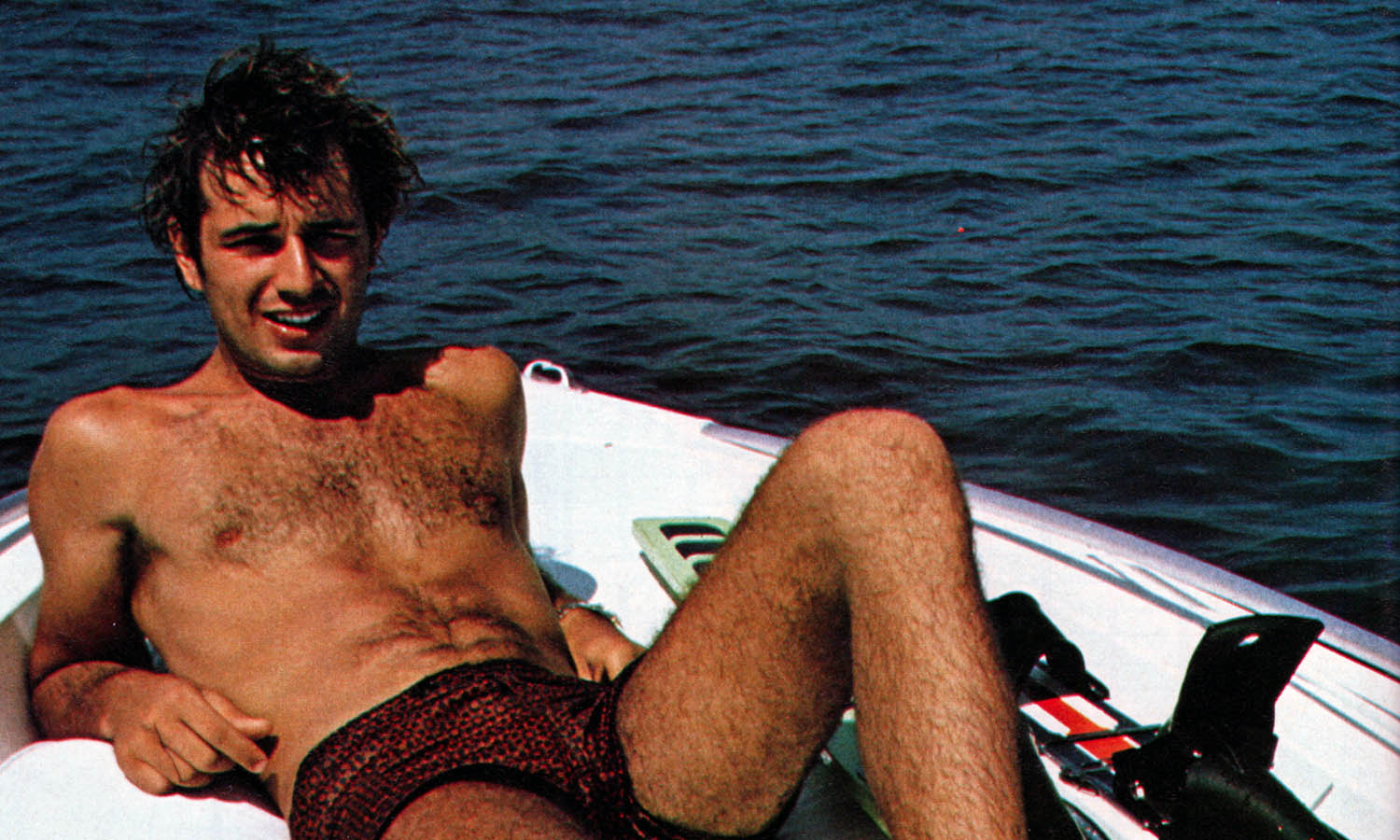

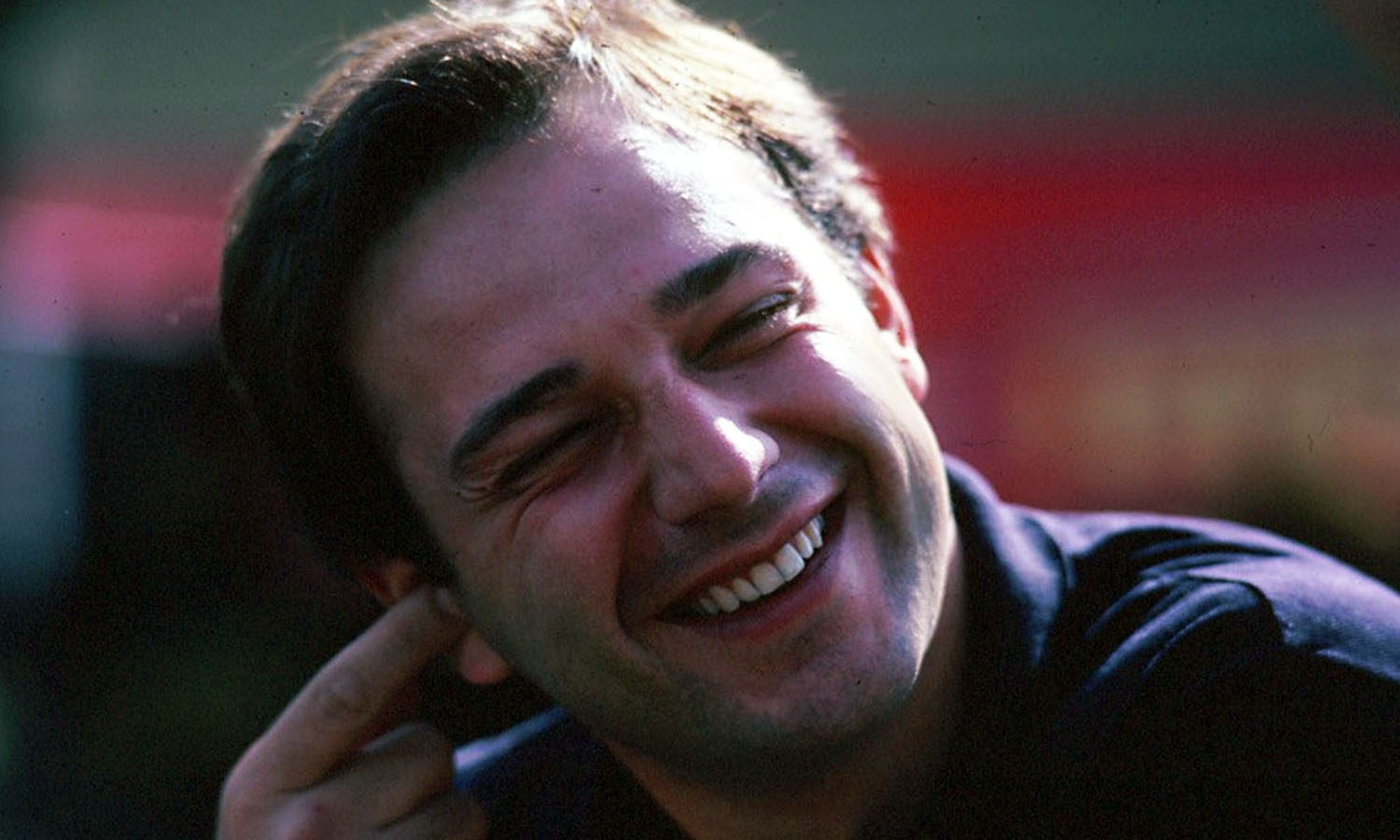

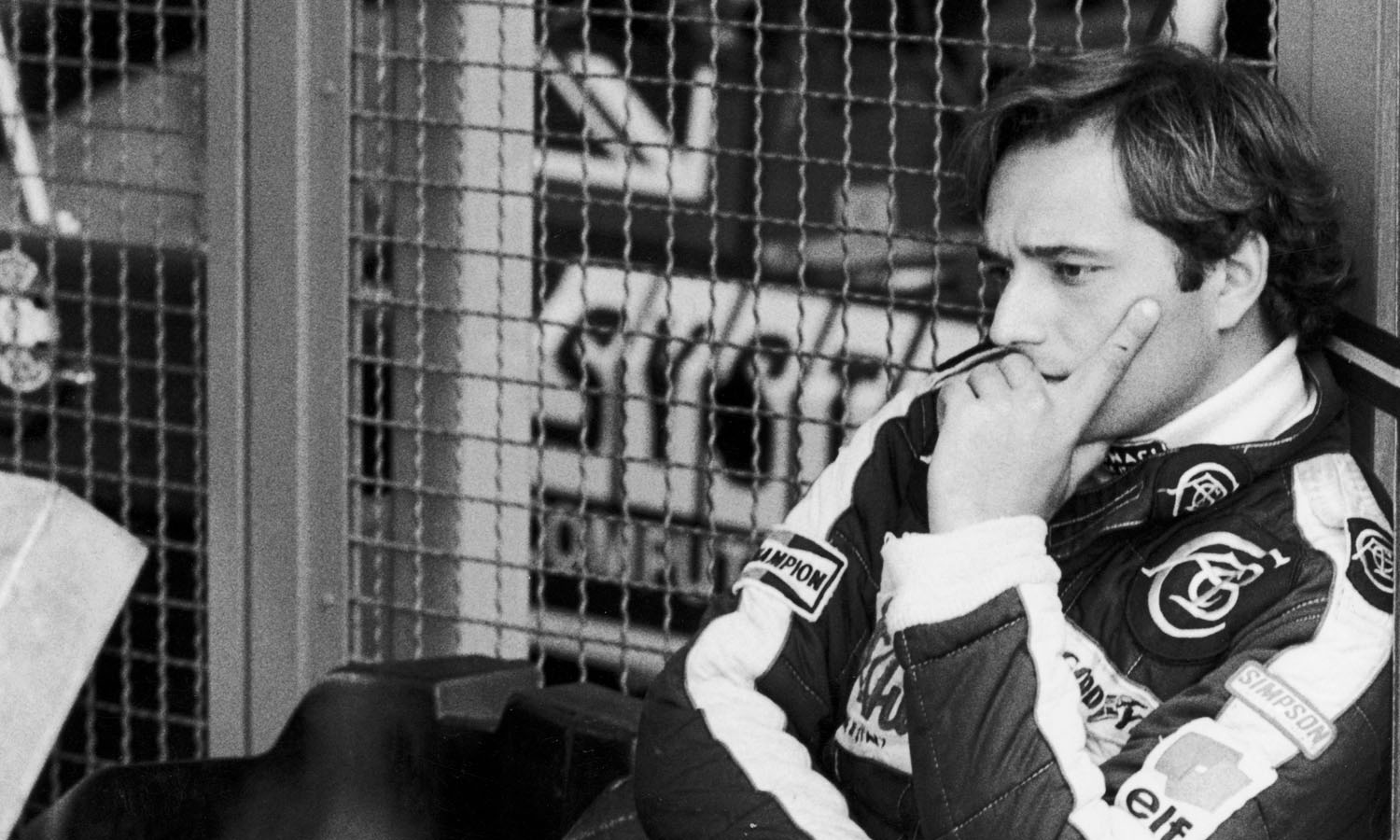

Elio always reminded me of Chris Amon. There was an abundance of natural ability, but also the old cliché about ‘too nice a guy’. It was as if God had given them the talent, but not the application to make the most of it. For both de Angelis and Amon, racing was one of the good things in life, but it was not life itself.

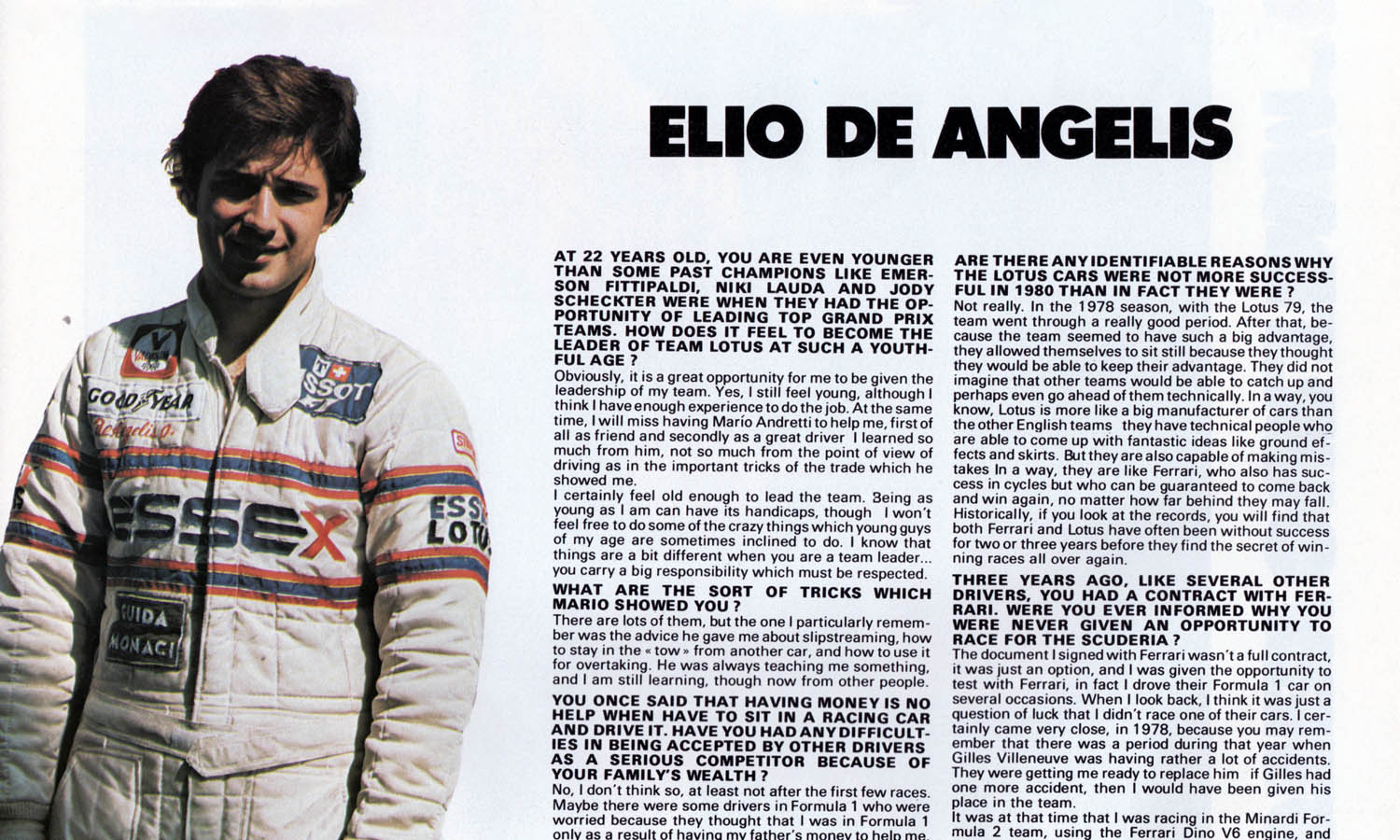

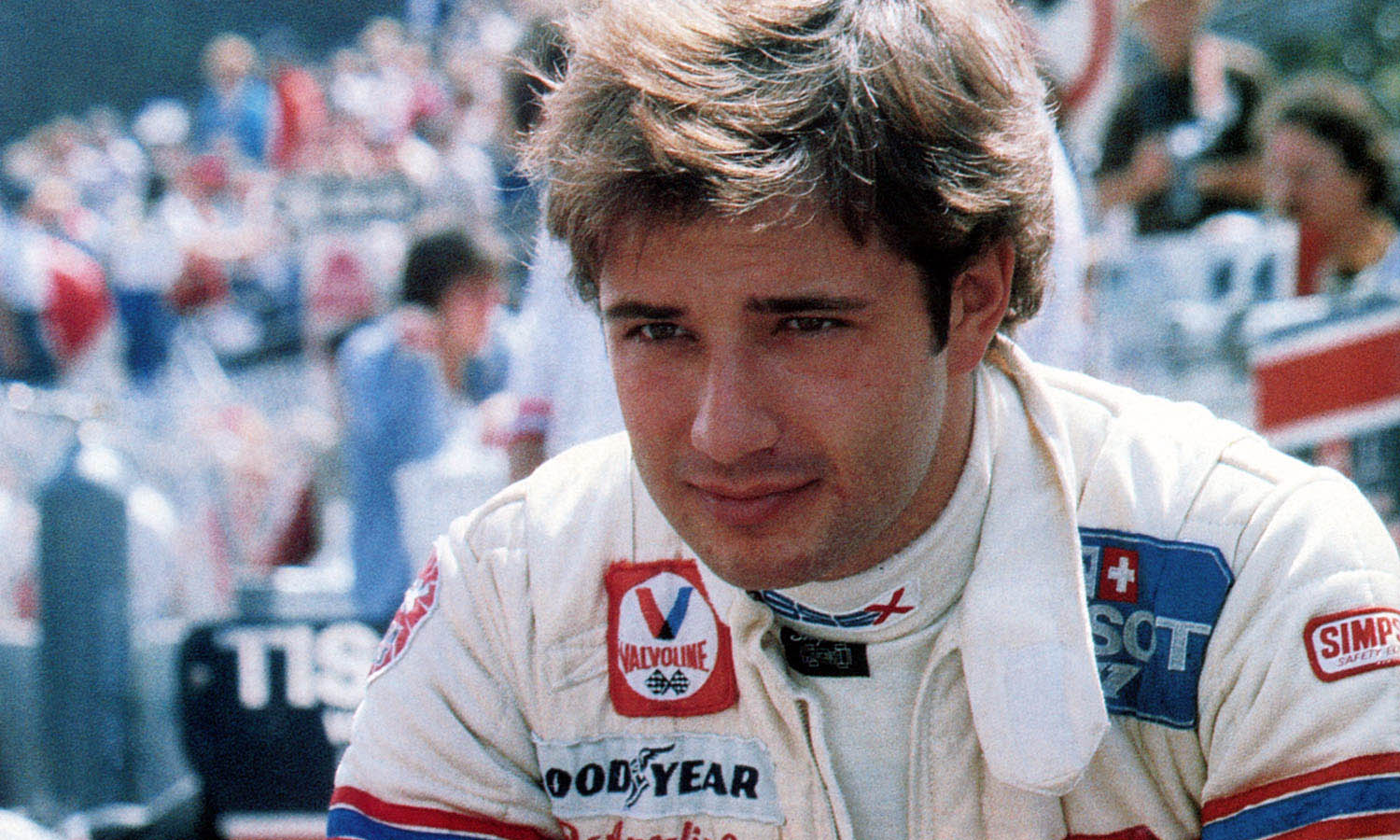

Neither was the most organised of men, and probably they would have had it no other way. Maybe upbringing had something to do with it. Both had been born into wealthy families, and grew up wanting for little. Both began racing at a young age: Amon was 19 when he made his F1 debut, de Angelis 20. Both had a fluent style and immense natural speed. In one important respect, though, they differed. It is so often said of a racing driver, particularly in this era, that he ‘relies too much on his talent’. Juan Montoya comes in for it today, and certainly there were those — Colin Chapman included — who thought it true of de Angelis.

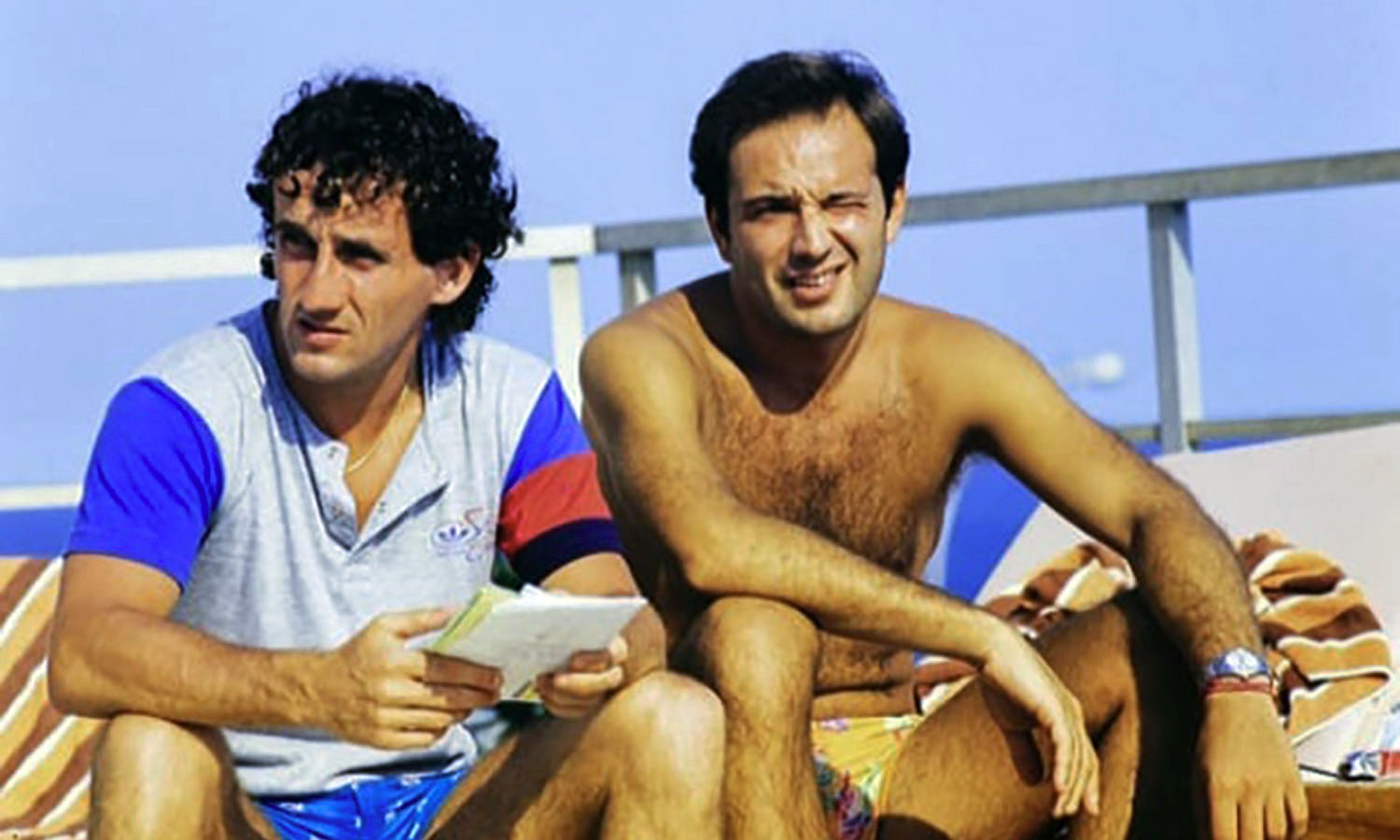

It is not by chance that the really great drivers of the last 20 or 30 years — Prost, Senna, Schumacher — worked unusually hard at their jobs, thinking constantly about how to make the car quicker, putting in the time. Amon, according to Ferrari’s Mauro Forghieri ‘the greatest test driver I ever worked with’, was another who put in the time. While his team-mate, Jacky Ickx, preferred to stay at home between races, Amon pounded round Modena day after day.

As with Prost, Chris usually went to the grid in a perfectly set-up car. Elio was not like that. It wasn’t that he couldn’t communicate with his engineers; simply, he believed that enough could be too much, and he hated testing. “I think it’s crazy,” Elio said. “The team owners complain about rising costs, yet they waste money on these stupid tests at each track. What difference would it make if we didn’t do it? There are two days of practice before the race, and that should be enough. I tell you, it would make no difference, except that maybe everyone’s times would be half a second slower. The same guys would still be at the front…”

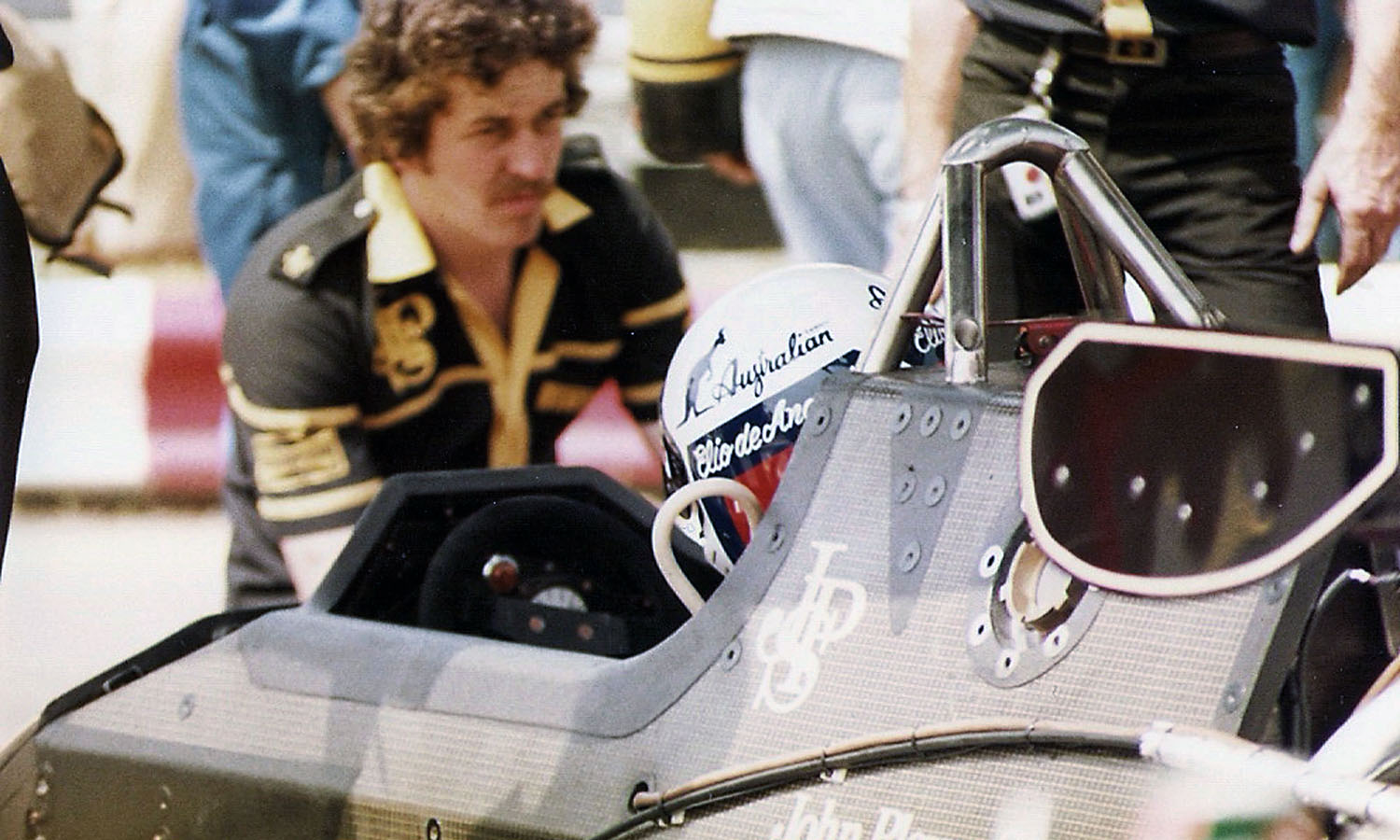

Having made his name in F3, de Angelis began his F1 career in 1979 — with Shadow. It was a rent-a-drive and the car was hardly competitive, but he did enough with it to impress.

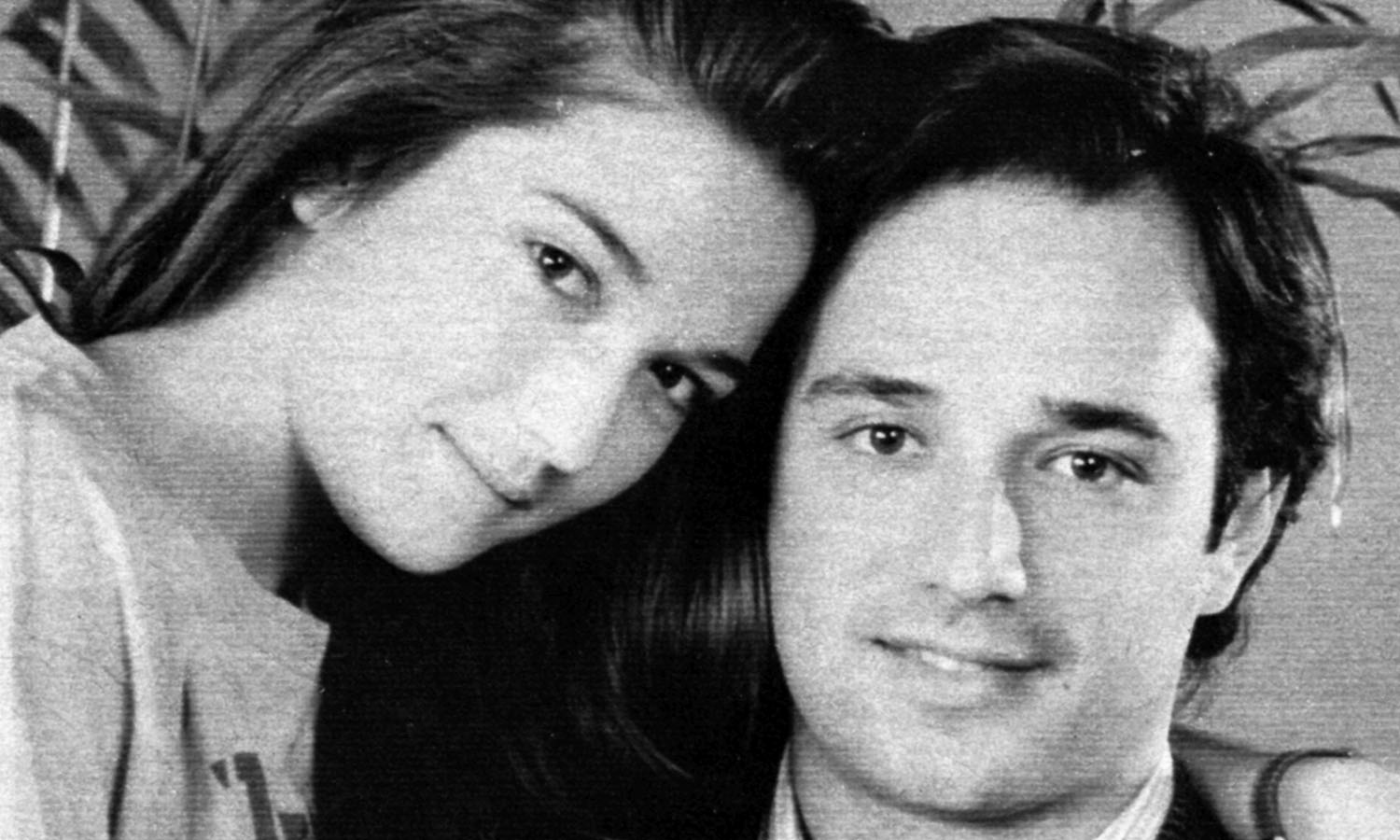

Jo Ramirez, then working for Shadow, became a close friend. “Elio reminded me so much of François Cevert, with whom I’d worked at Tyrrell. Charming, completely genuine — and a very good driver. I remember the day he signed the contract. It was his first F1 drive, and we went out to celebrate to a coffee shop in Northampton called Cagney’s, where we had hamburgers and chips! For all his wealth, Elio was a very down-to-earth person. He used to come to my house and play the piano — like François, he was classically trained.”

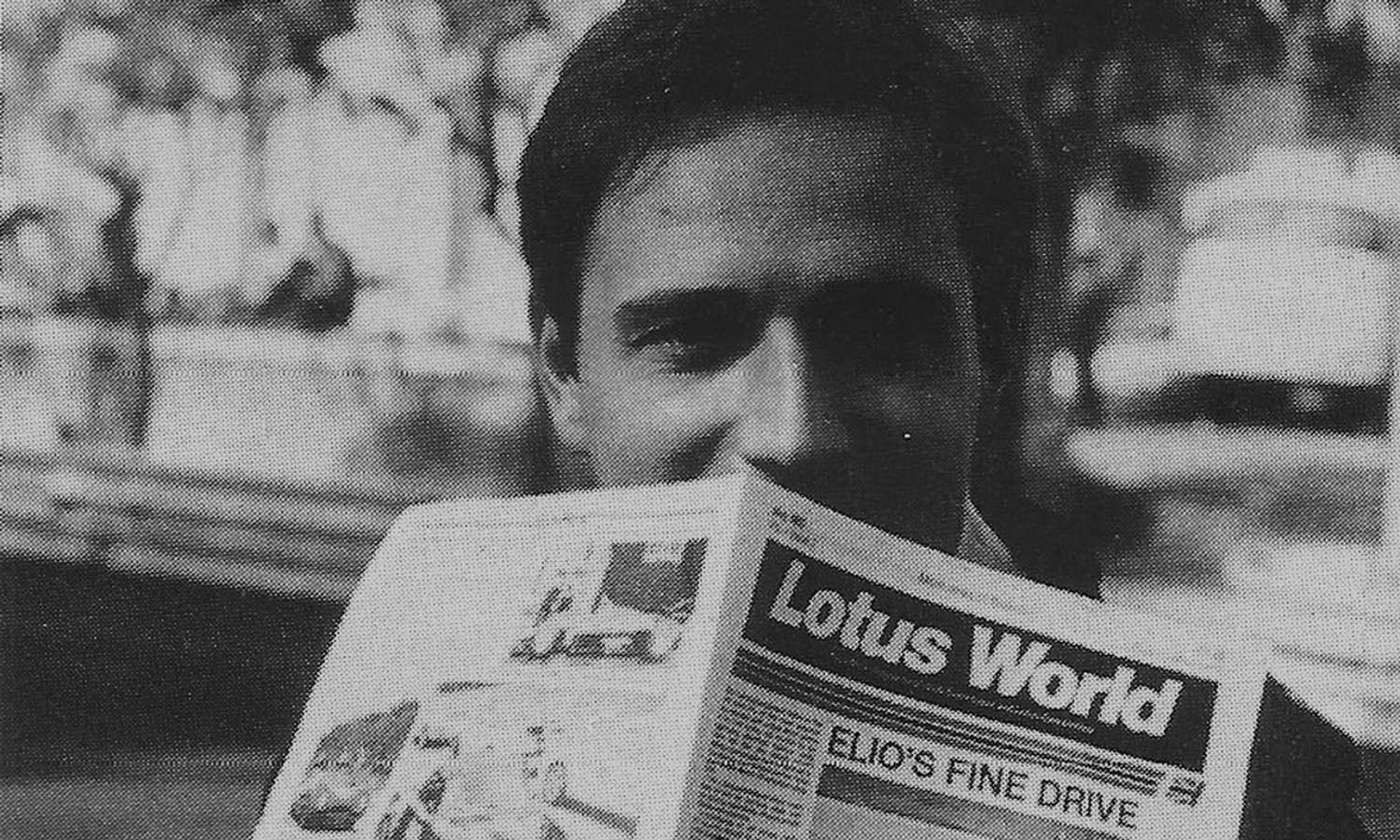

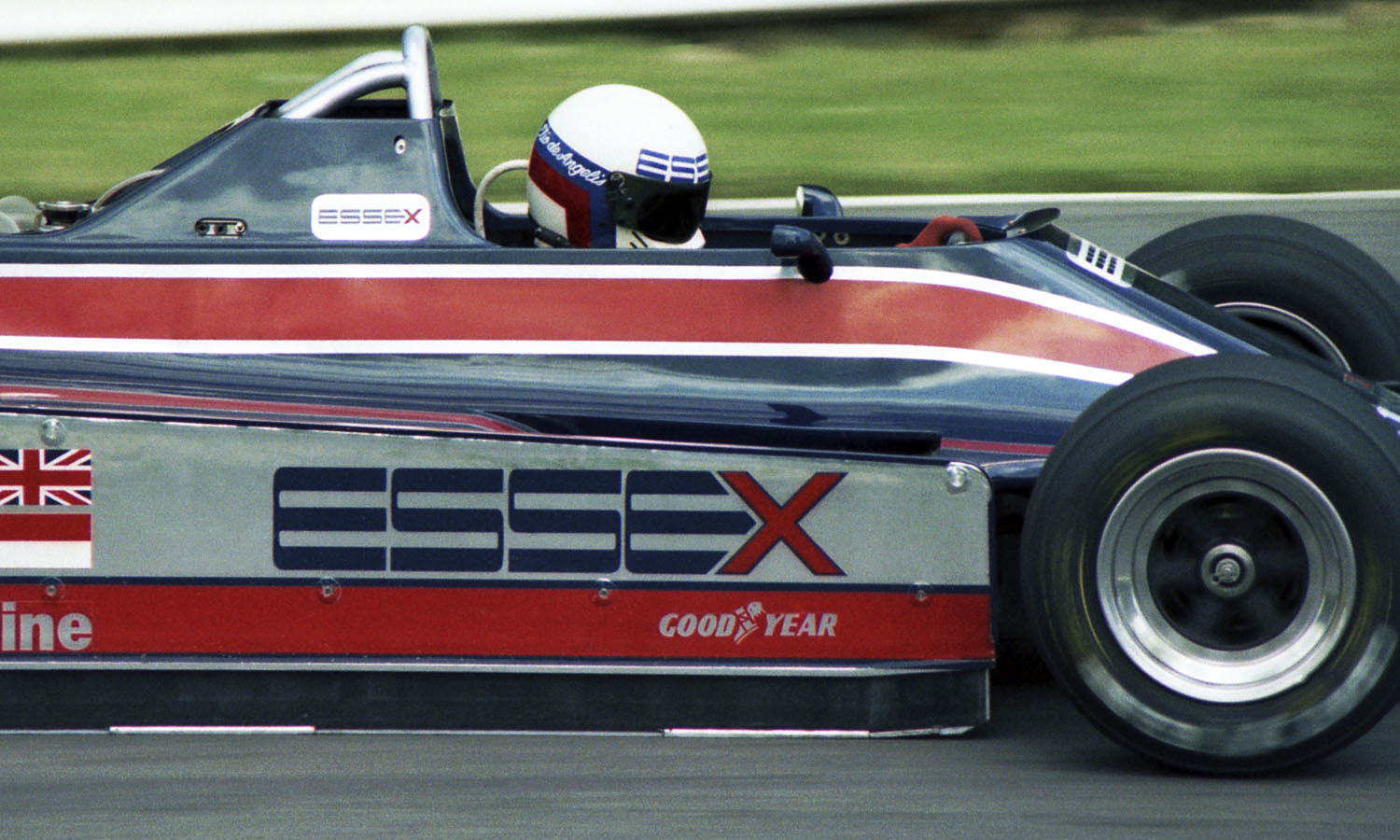

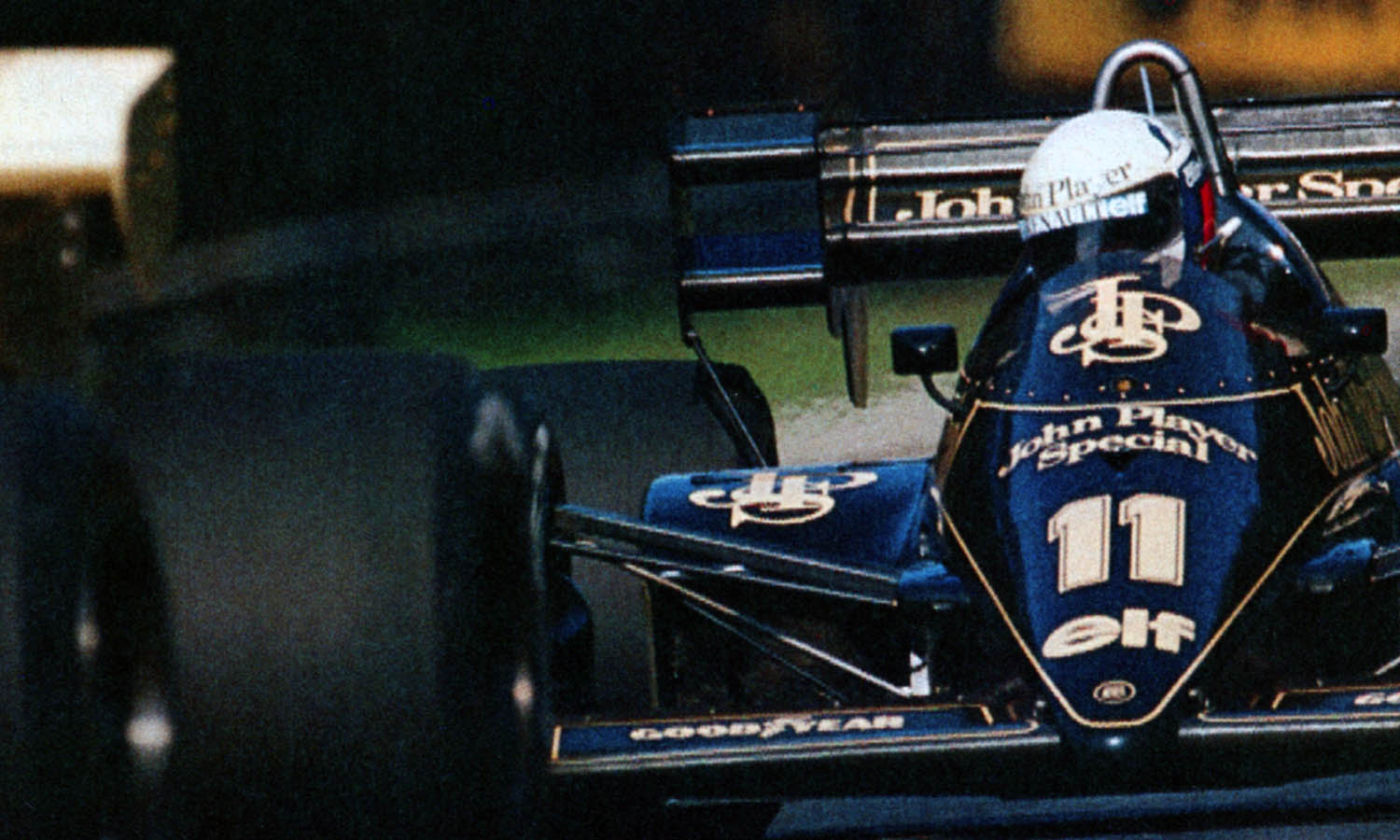

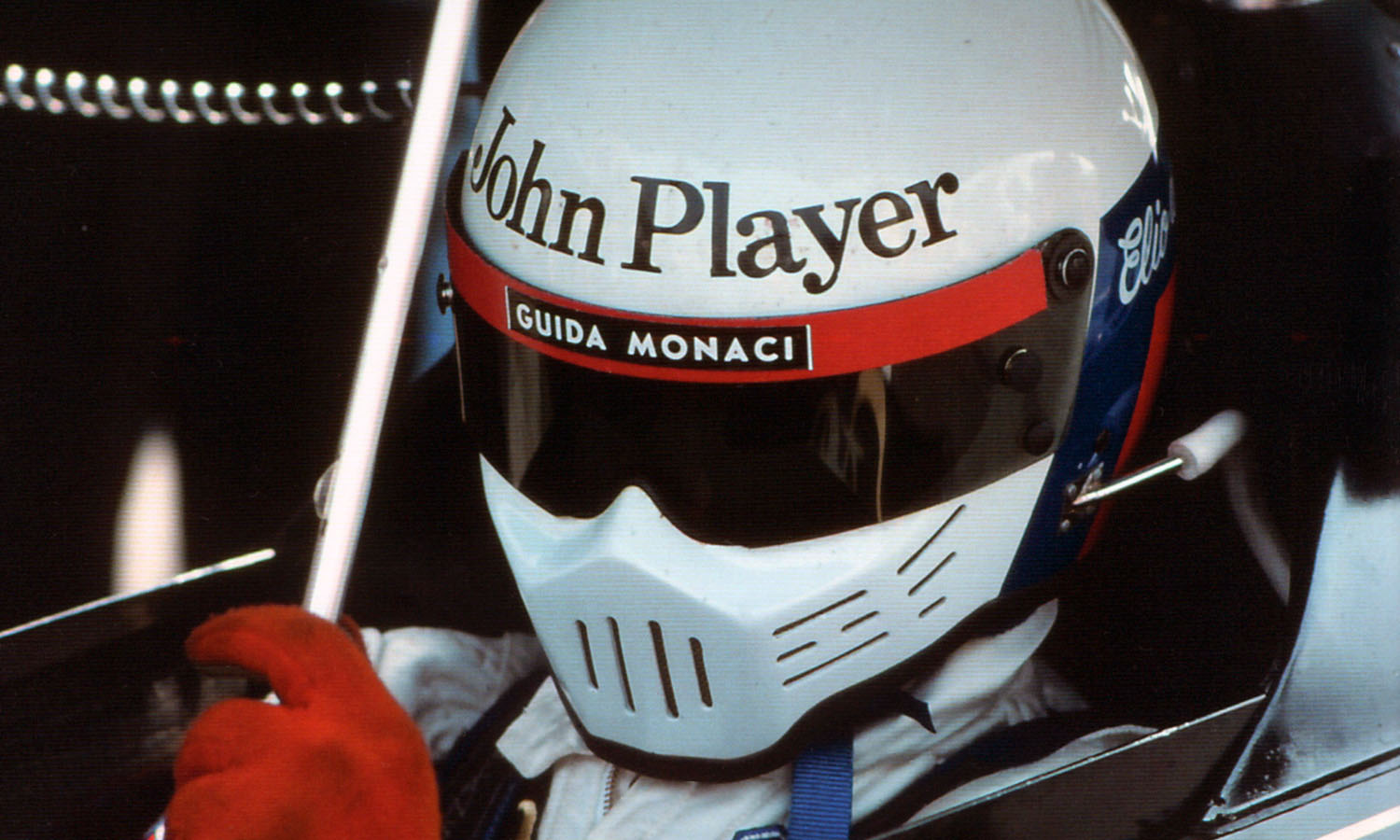

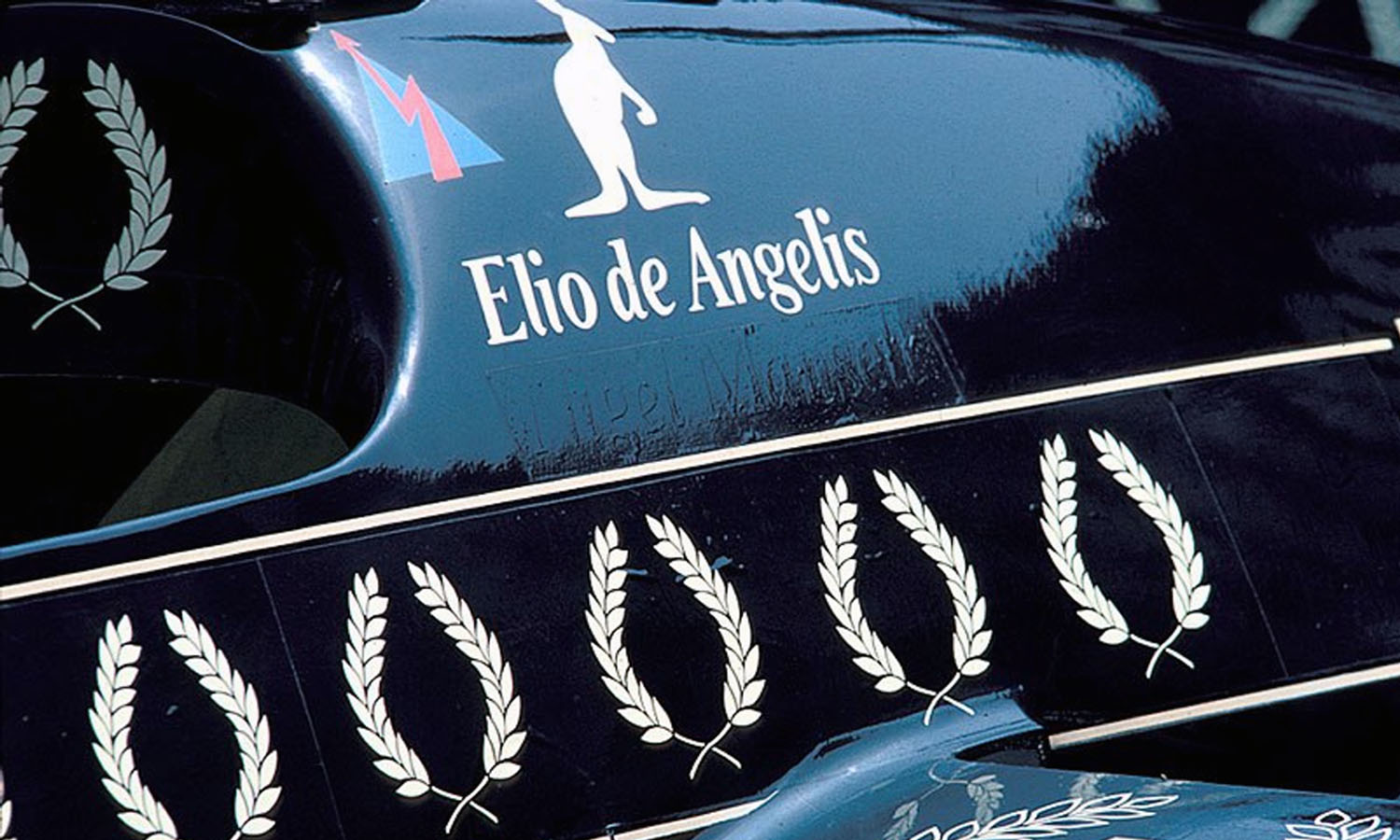

The pickings were thin in ’79: three points. But clearly de Angelis was quick, and if there were anything Colin Chapman liked more than a quick driver, it was a rich quick driver. De Angelis signed a Lotus contract for 1980, as team-mate to Mario Andretti, and would become synonymous with the team, staying there for six seasons, always with quick team-mates: after Andretti came Mansell, then Senna. In 1982, the year of Keke Rosberg’s world championship, de Angelis beat him — by about a foot — in the Austrian GP, and that was the last time we were ever to see Chapman vault the pit wall and hurl his cap into the air. In December he died, after a heart attack, and probably de Angelis never felt quite the same about Lotus again.

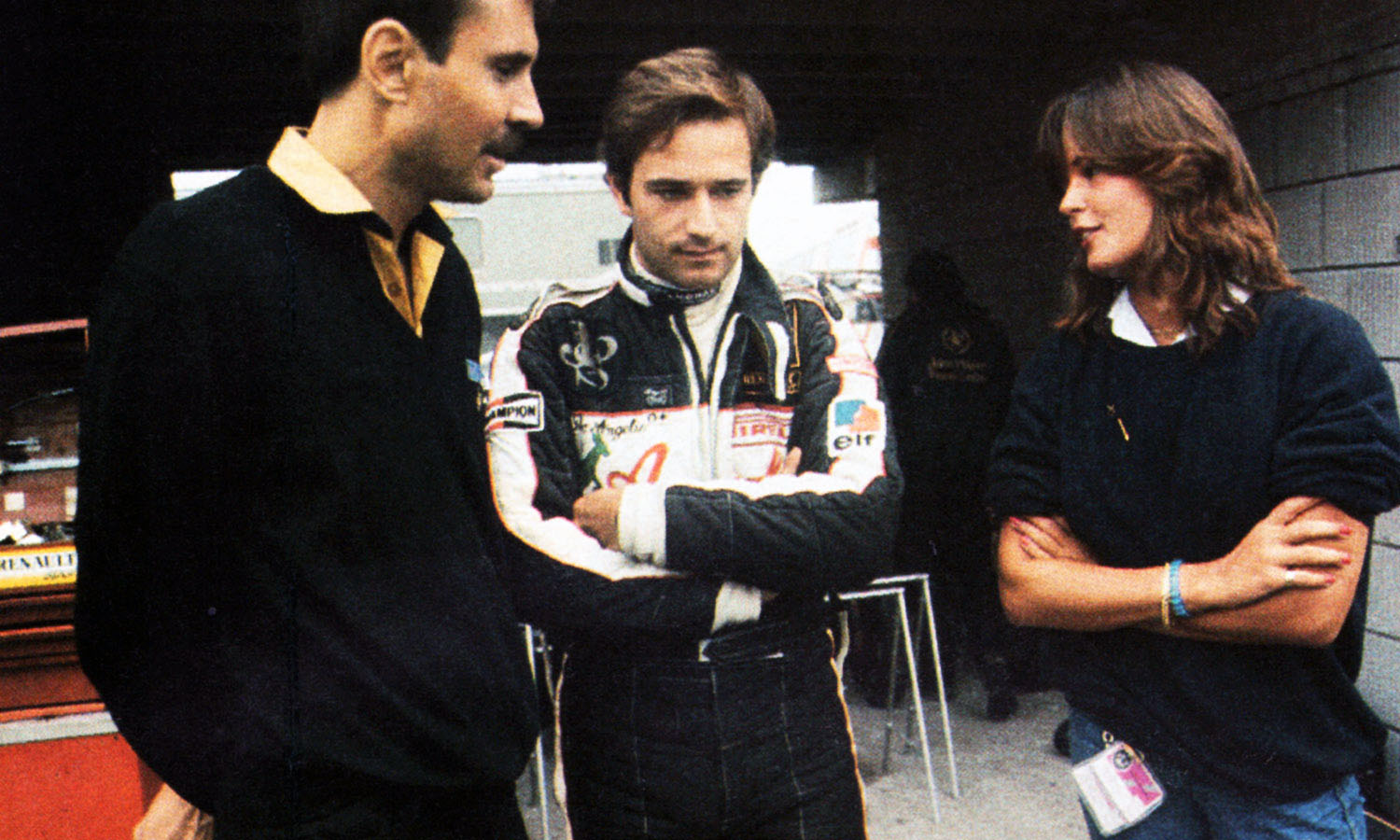

By 1985 Senna was his team-mate, and there was much about Ayrton that Elio found hard to warm to. Straight after final qualifying at Montreal, Senna was into heated discussion with team principal Peter Warr and the engineers, while de Angelis lit a cigarette, took his girlfriend’s hand, and strolled off to the paddock, savouring the moment. Ayrton was second on the grid, Elio on the pole…

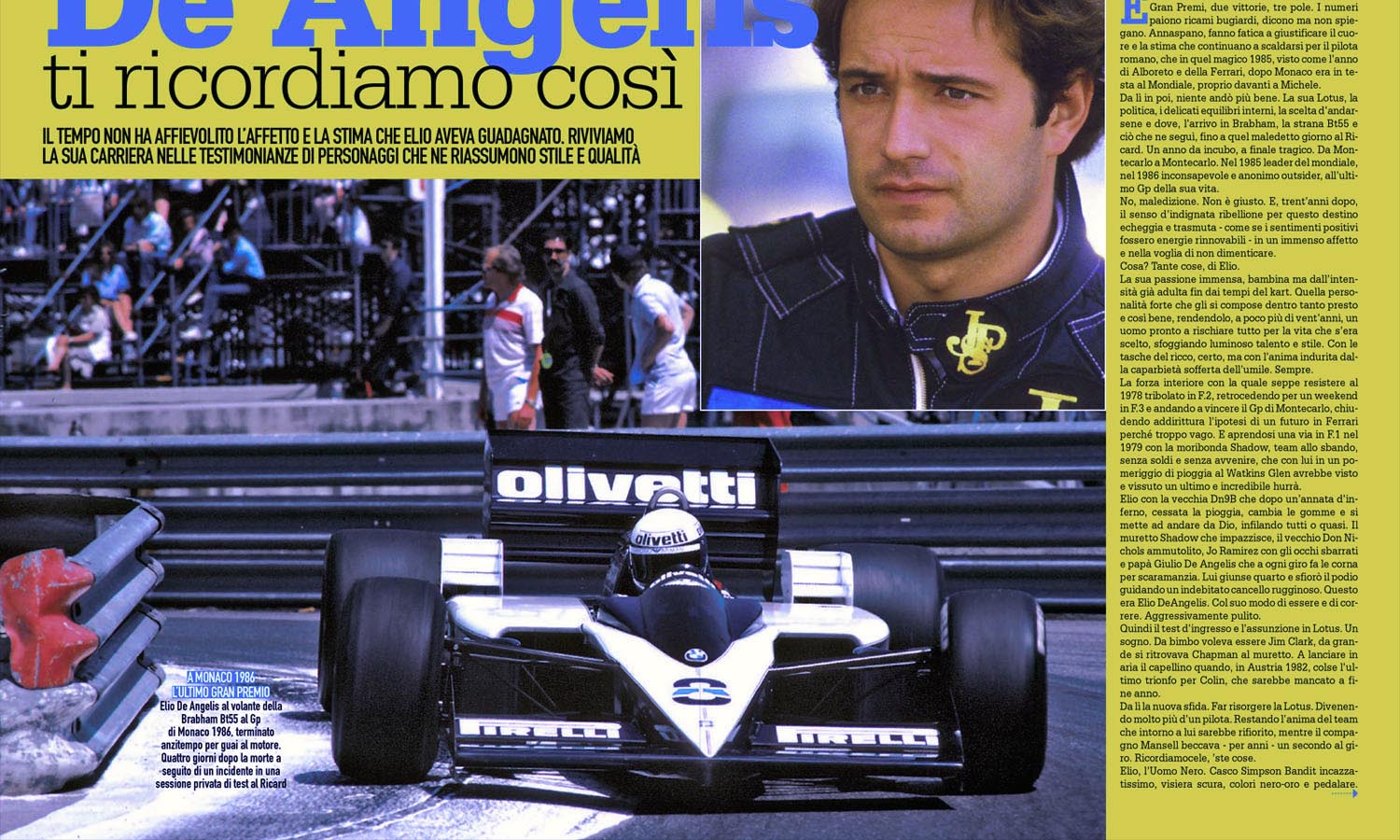

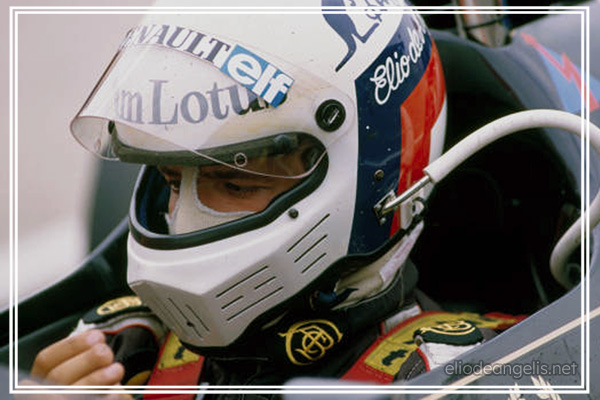

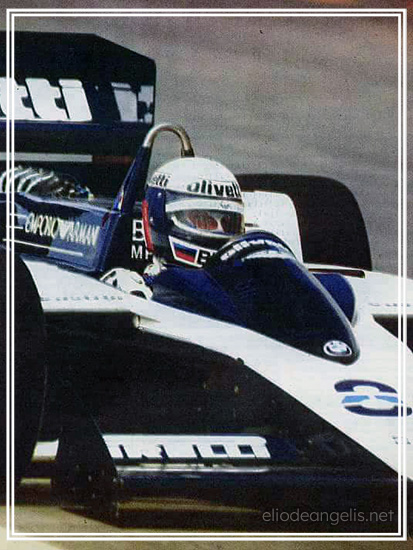

For 1986 there was a move to Brabham, where Gordon Murray’s BT55, with ‘laydown’ BMW turbo engine, awaited. Four races into the season the unorthodox car, although blinding in a straight line, had scored but one point, and at Monaco de Angelis was the slowest qualifier.

So to Ricard for the fateful test. Onlookers reported that, as Elio went through the flat-out left-right sweepers at the end of the pit straight, his car lost its rear wing. Eventually it came to rest, upside down. Alan Jones was the first driver on the scene. “There was no fire when I first got to the car,” he said. “Just some black smoke. Problem was, we couldn’t right the car because it was too heavy. There were a couple of marshals there in normal clothes — shorts, in fact — and all they had were these piddling extinguishers, which did nothing. Finally, a truck arrived, with a big extinguisher, but it took them ages to get it going, and when they did they stood about eight feet away, and blew all the powder in towards the cockpit, and not the engine. Awful, just awful.”

“It was such a waste of a life,” mused Ramirez. Even now it upsets me to think about it, the way he suffered — he wasn’t hurt in any way, but he couldn’t breathe, because the fire took all the oxygen, and then they sprayed all that powder into the cockpit. Shameful.”

As for Rosberg, he had lost his closest friend and it set the seal on his decision, already pencilled in, to retire at season’s end.

“After the accident I remember driving back from Marseille with Mansell. Not much was said — in fact, Nigel came out with one sentence during the whole journey: ‘How long is a piece of string?’ And that’s the single sentence I’ve heard in my life that I remember better than anything else.”

© 2006 Motorsport Magazine • By Nigel Roebuck • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended