Elio de Angelis was more than just a 'rich kid' - he was a naturally talented driver who, on his day, could outperform Senna

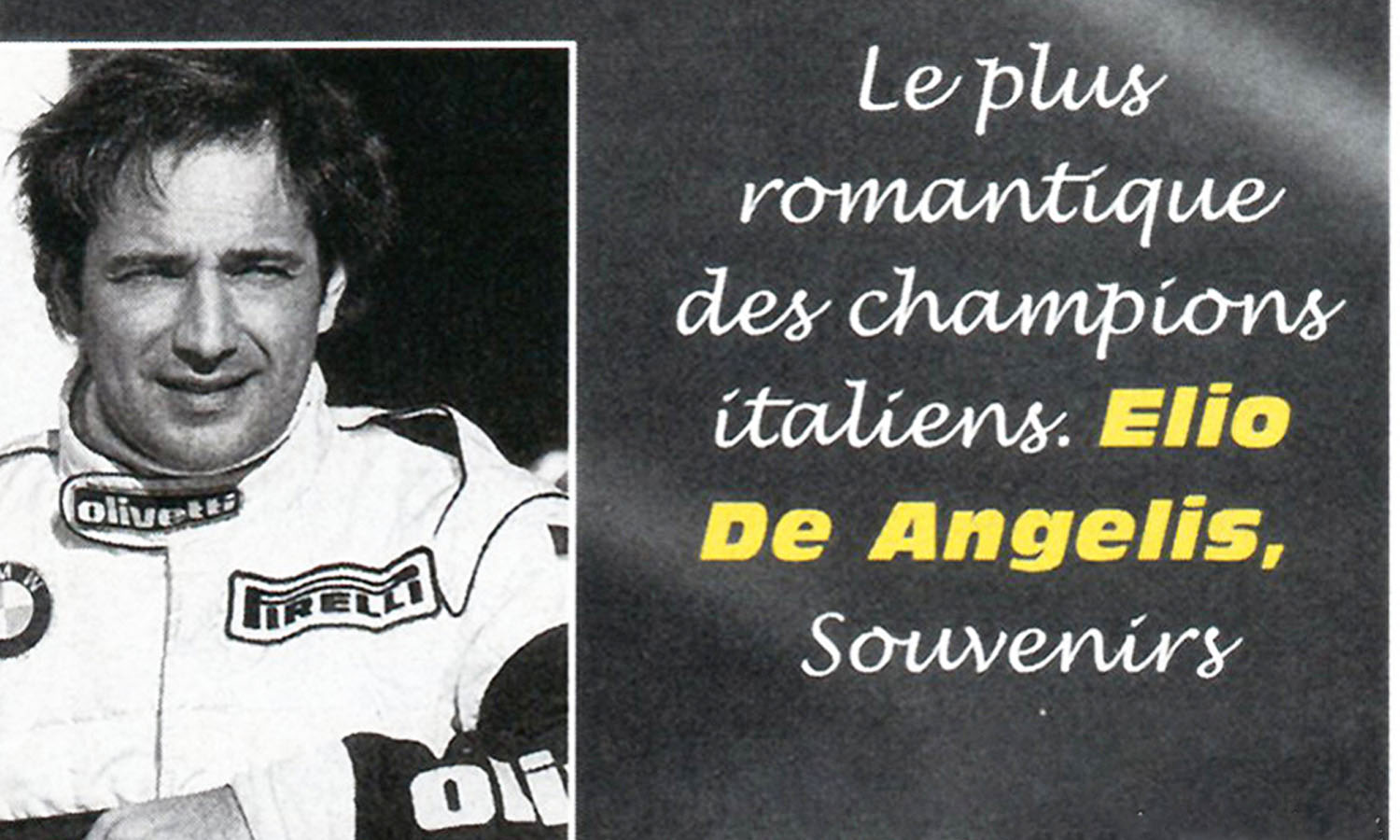

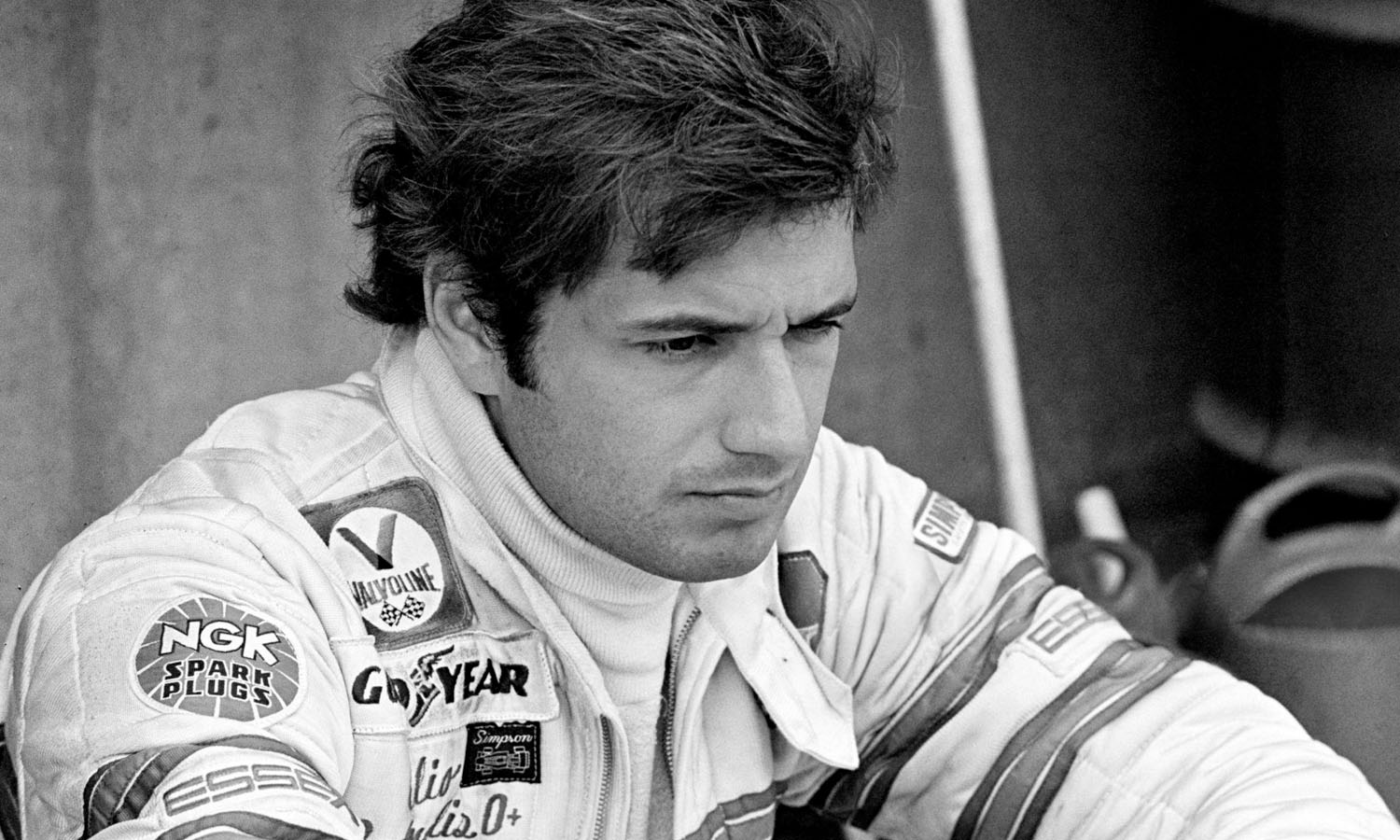

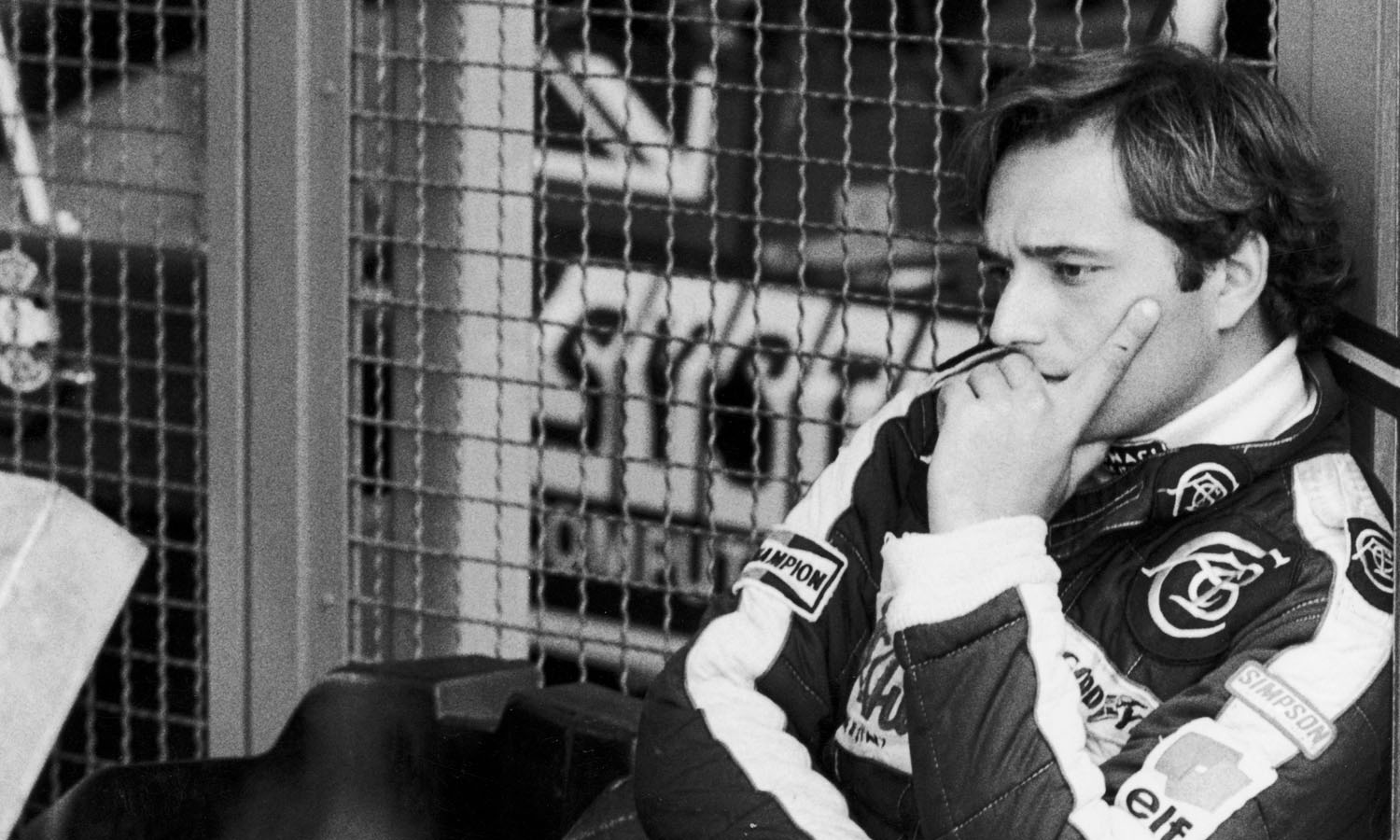

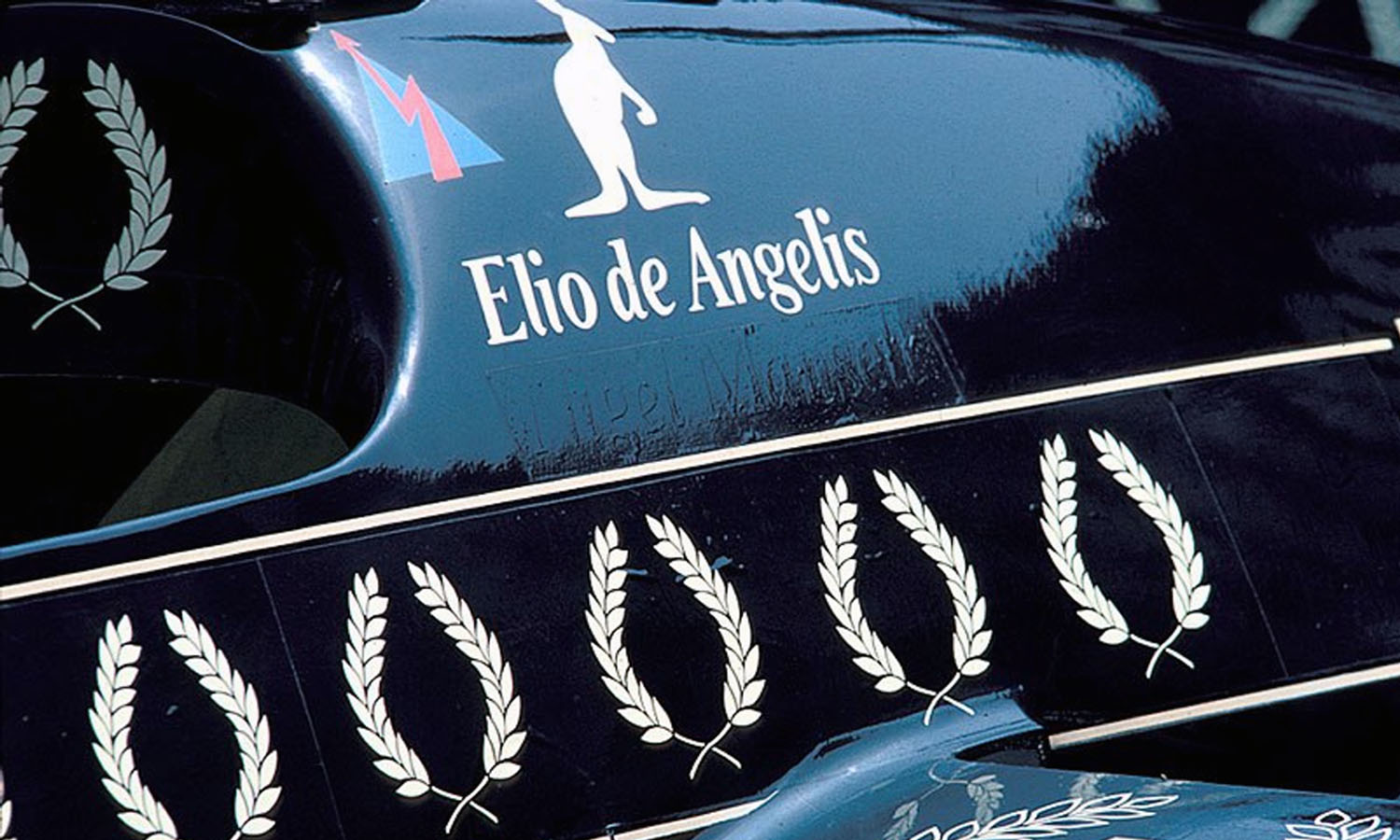

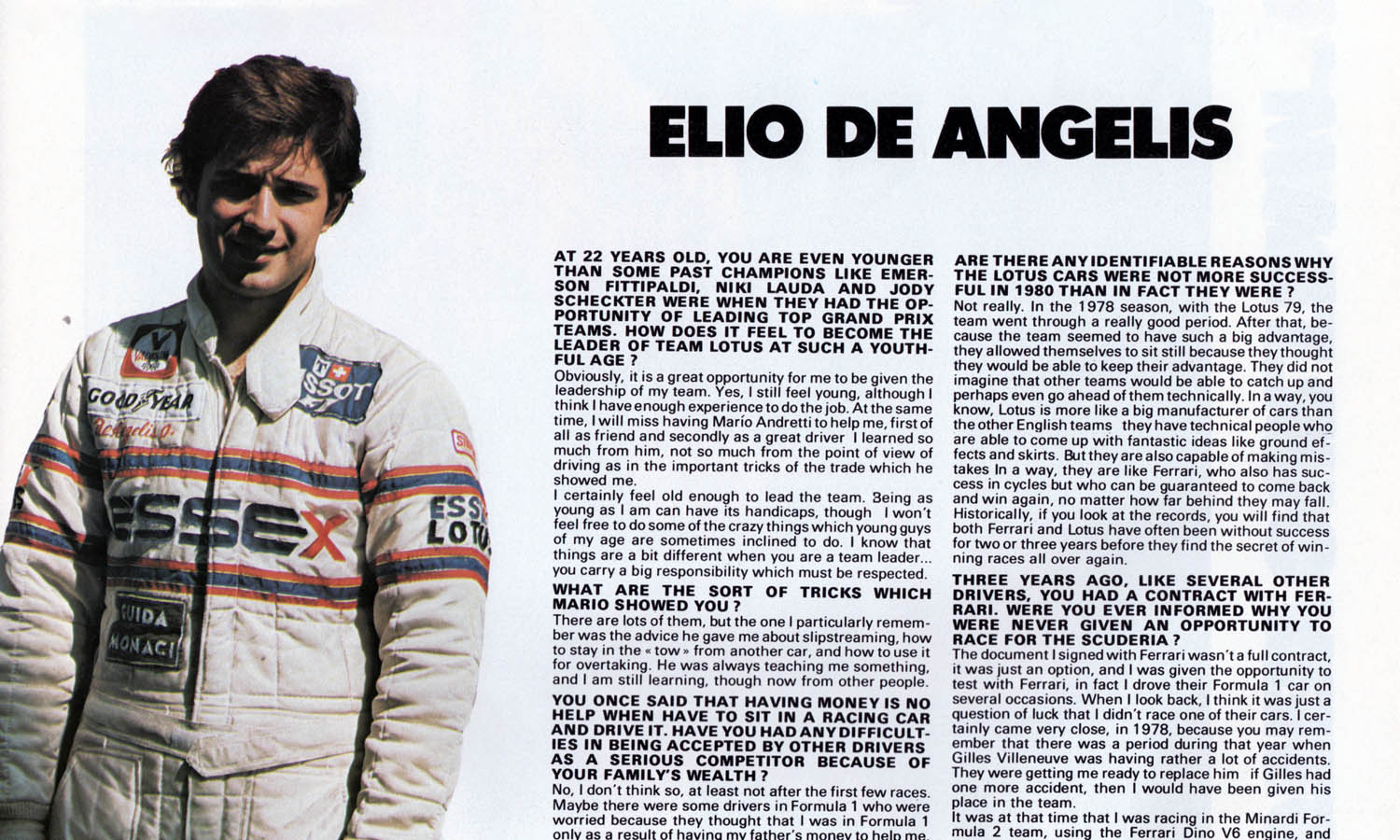

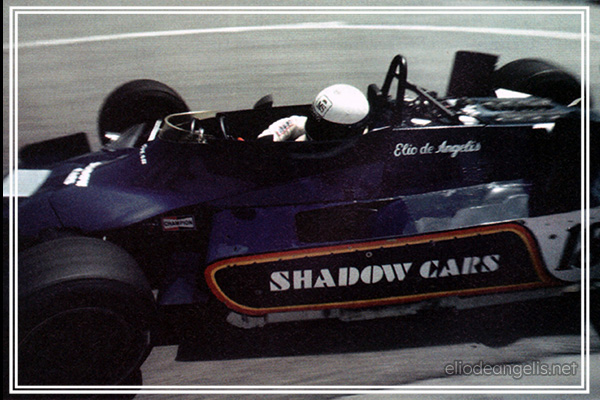

Elio de Angelis, whose death from race-track injuries 25 years ago will be commemorated on May 15, is remembered with endearing fondness by almost everyone who knew him during his seven-year Formula 1 career. The eldest son of a wealthy Roman family involved in the construction business, he was dismissed by critics as a dilettante in the junior formulae, then joined the Shadow team as a pay-driver for his debut season in 1979 in exchange for a rumoured $25,000 per race.

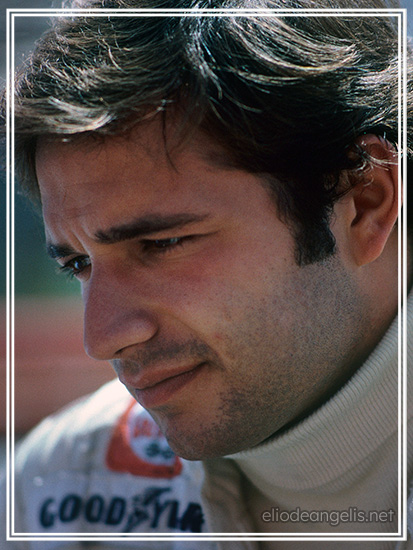

Although de Angelis confounded those early critics, his record of three pole positions and two wins from 108 Grand Prix starts hardly marks him down as a ‘great’. But he had a charm and modesty that belied his wealth, together with an incipient talent that deserved respect, however inconsistently it may have blossomed. As this tribute will show, the path to the top of his profession was not exactly strewn with rose petals.

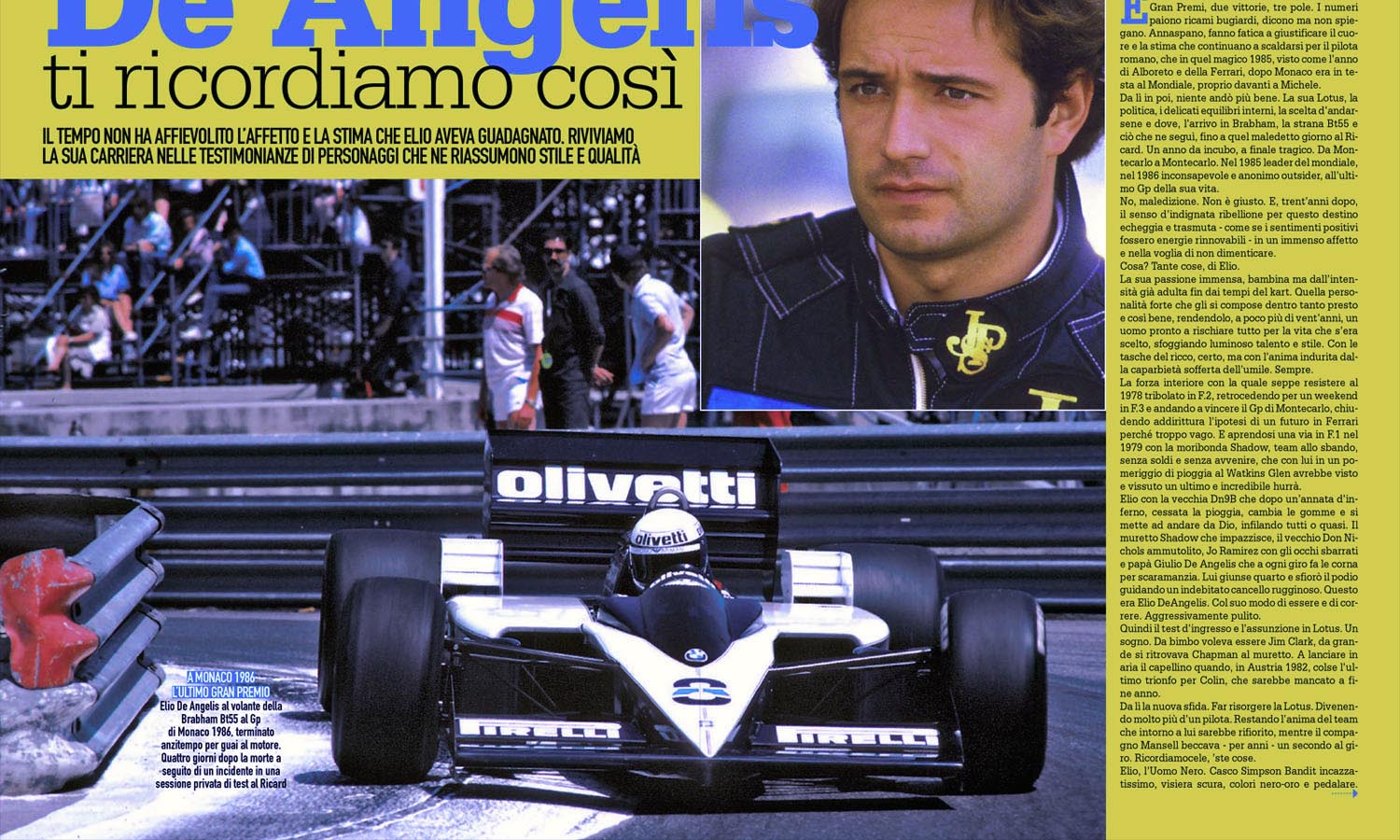

The circumstances of Elio’s violent death caused bitter distress within the Brabham team, which had never lost a driver to a mechanical failure before, and caused Gordon Murray, its senior engineer, to consider his future in the sport. The cause of the crash was the loss of the Brabham-BMW’s rear wing, which sent it crashing and overturning into a fast corner.

The wreck caught fire and the marshals, most of them wearing shorts, were disgracefully slow to assist. It was half an hour before a helicopter arrived and de Angelis — whose external injuries were minor — died in a Marseilles hospital the following day of smoke inhalation. He was 28 years old.

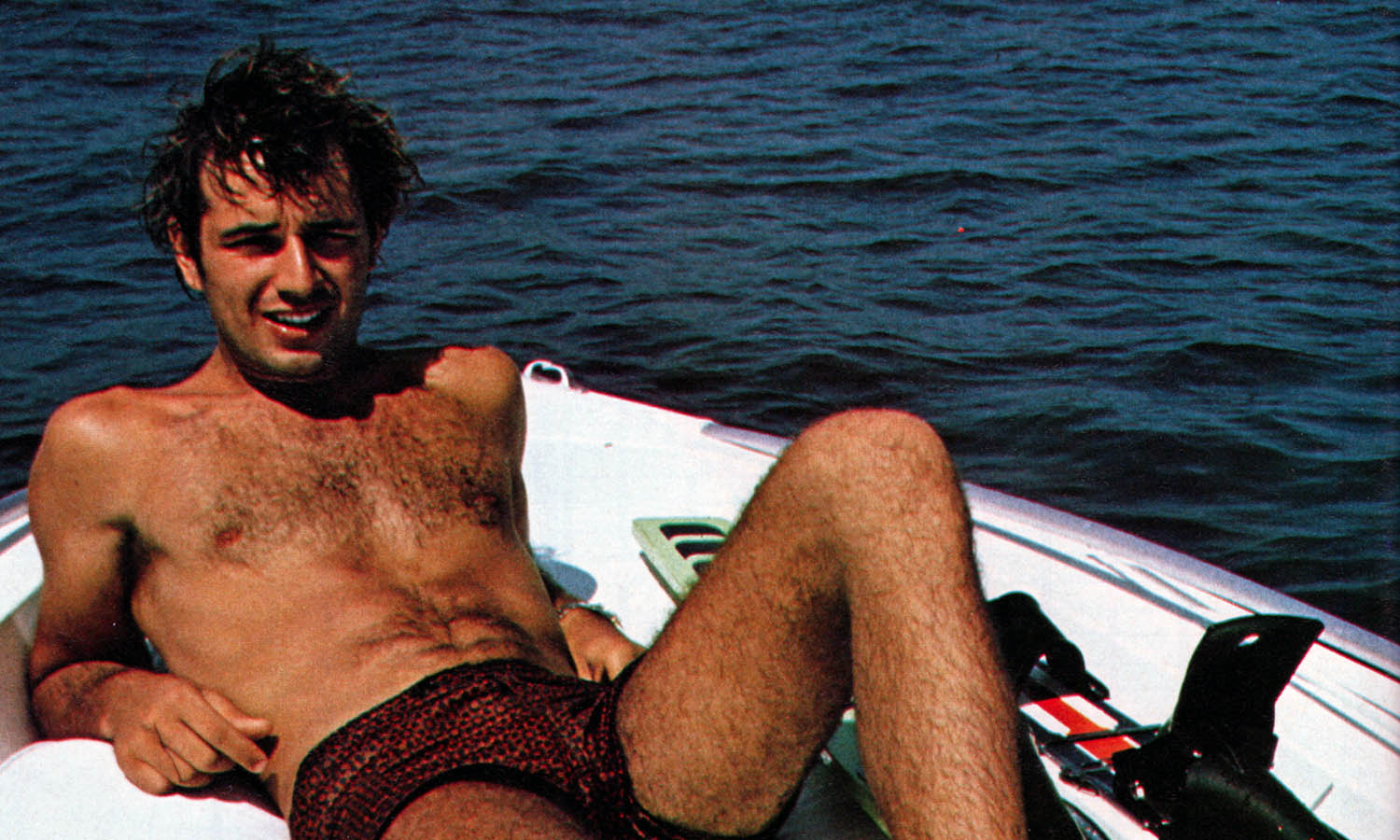

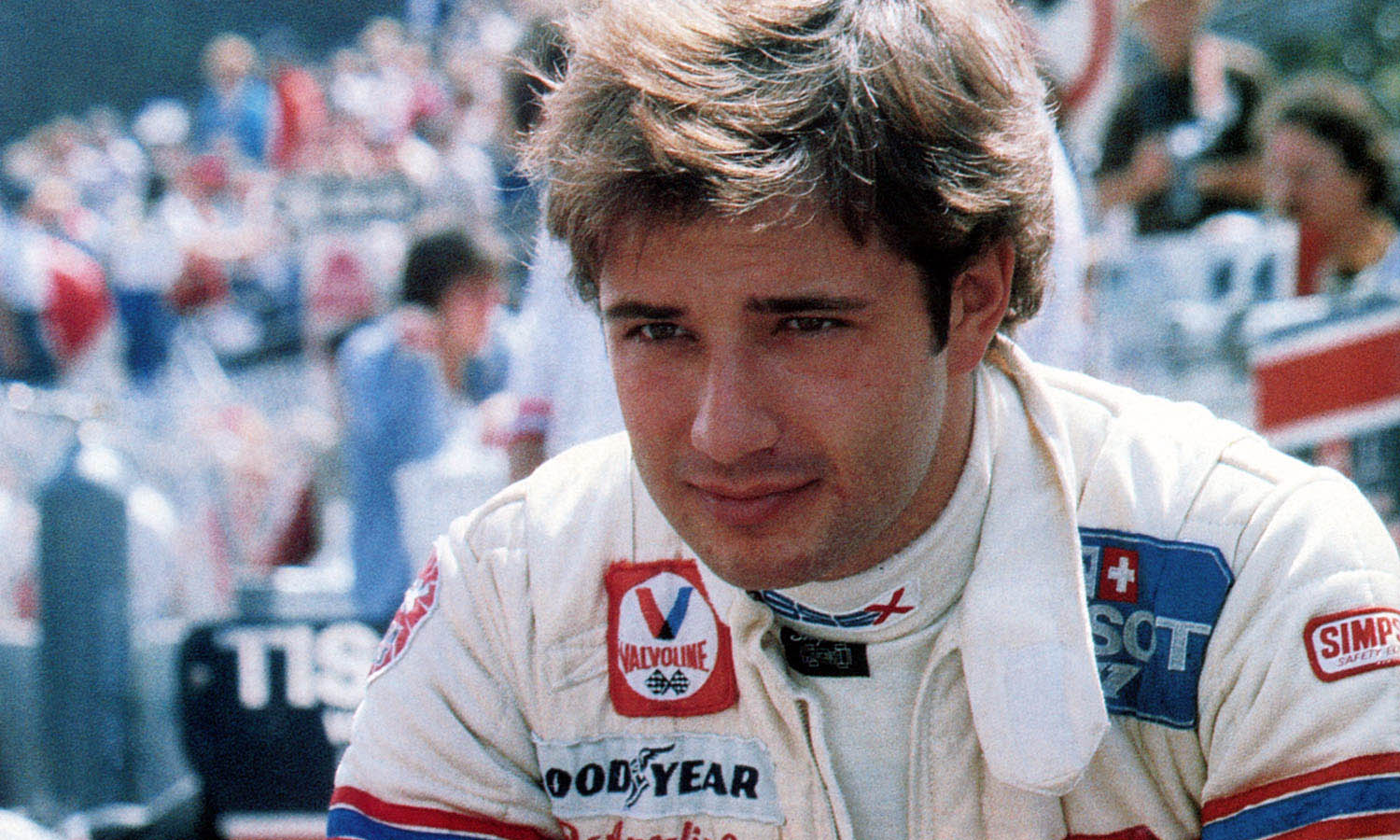

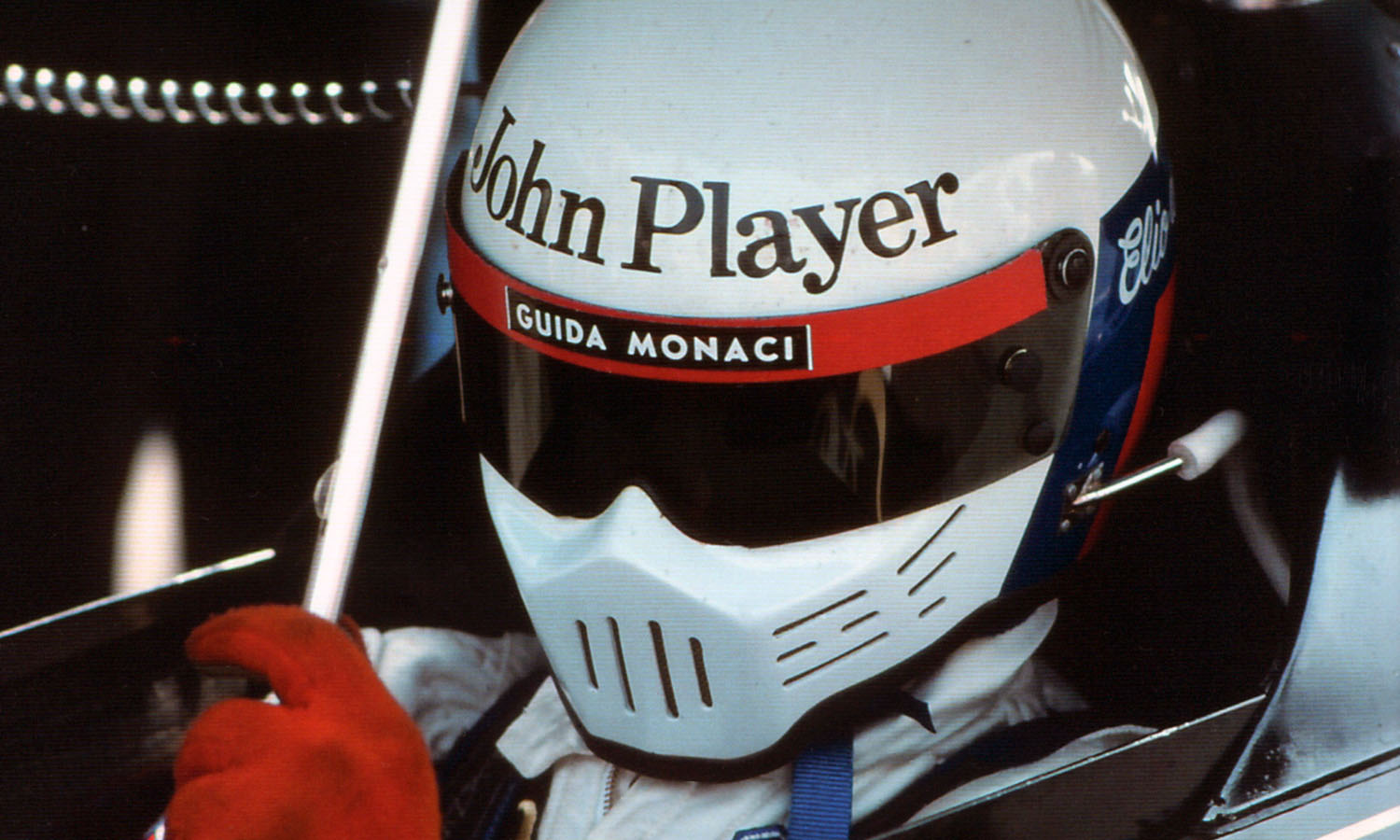

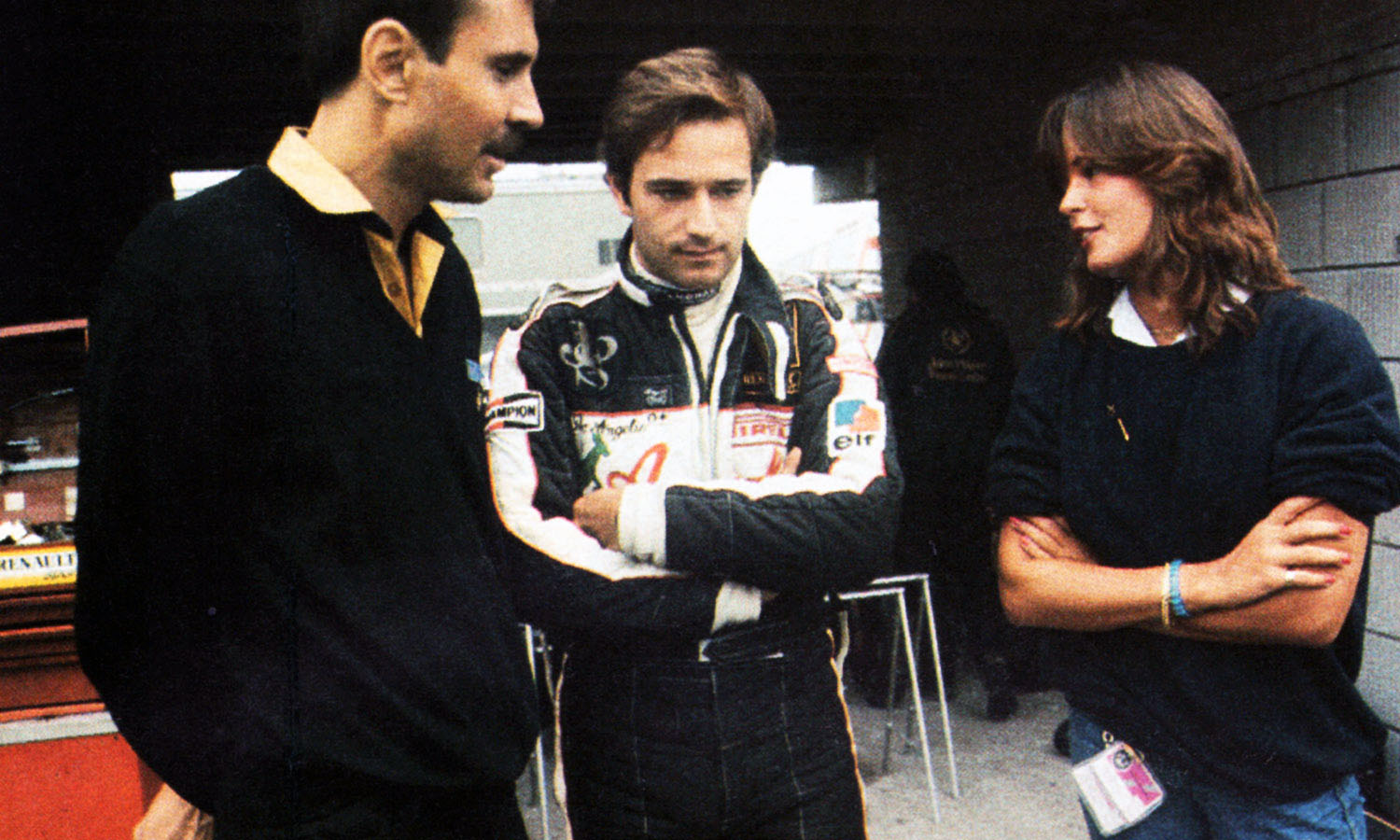

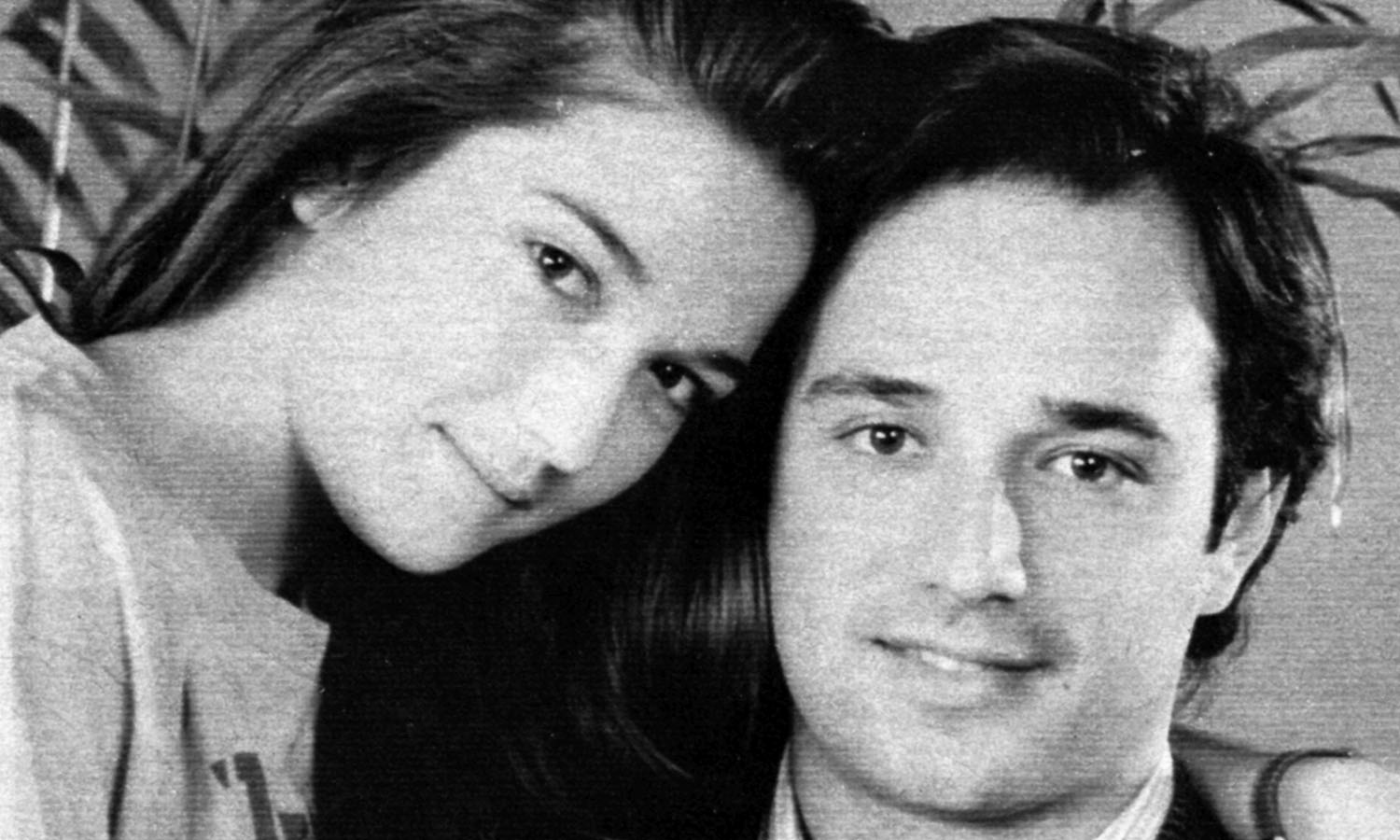

Thirty years ago, when there were only a couple of dozen reporters at a Grand Prix, F1 drivers were comparatively approachable, Elio more than most. With his Brando-esque features, fluffy hair and pastel-coloured sweaters, he could have been mistaken for a professional tennis player, although the odd cigarette hinted otherwise. His gifts included an uncannily good command of the English language, so it was a surprise to discover that he made no attempt to speak German with his long-term girlfriend, the fashion model Ute Kittelberger. This was perhaps a pointer to his reluctance to put an effort into anything that didn’t come naturally to him.

From the beginning, he and I had an easy and open friendship. In a conversation recorded on the eve of his first-ever GP, in Buenos Aires in 1979, he said, “You can buy your way into F1. But once your arse is in the metal monocoque, the only person who can help you is yourself.”

Elio was the oldest of four children born to Giulio and Giuseppina de Angelis: after him came Roberto, Andrea and Fabiana. Giulio had raced powerboats with some success and owned a Ferrari. He enjoyed taking his sons to watch car races, which gave them a lifelong love of motorsport. Although the boys were allowed to race (all three would win the national karting title), Giulio ruled that only one of them — Elio — would be given an opportunity to take his ambitions further. That way, the business dynasty would have a chance of continuing if the worst should befall the first-born.

This edict evidently gave rise to fraternal resentment, as Elio’s long-serving mechanic Nigel Stepney was to discover. “His family — his father and the two brothers — put him under a lot of pressure,” says Stepney. “If he was slower in practice, they wanted to know why. If something went wrong on his car, they wanted to know why it hadn’t happened to the other one, too. Elio never performed well when they were there, and he used to love racing in America because it was outside their area and he could relax. At least the father understood about the sport, but if Elio was racing anywhere close to Italy, or where the family could come, the brothers were… Well, painful.”

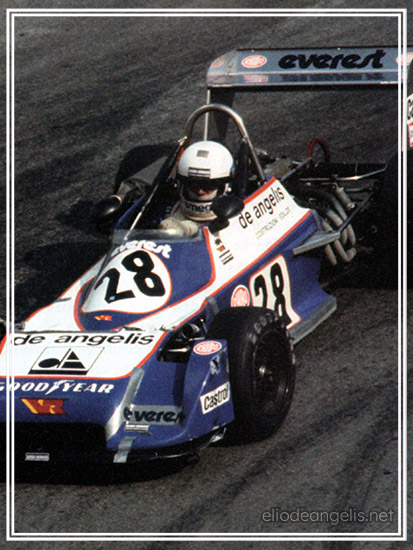

The boy was certainly gifted, with strong musical and artistic streaks. His talents carried over into motorsport, and by the time he was 18 he had three successful seasons of karting behind him. By the end of 1977, at the age of 19, Elio had won four races in the Italian championship, finished second in the Monaco Formula 3 classic in a Chevron-Toyota funded by his father, and been given two Formula 2 starts in a Chevron-Ferrari run by Giancarlo Minardi’s Scuderia Everest.

The collaboration with Minardi continued into 1978 but Elio had concluded that the overweight V6 Dino engine was uncompetitive. Sensing that he needed to demonstrate his ability wherever possible, he decided to have another crack at the Monaco F3 race, for which he dug out the year-old Chevron. In a sensational race this calculated gamble paid off with a win in the final from sixth on the grid, even if he took the opportunity to elbow race leader Patrick Gaillard off the road in the process. In those days Italian F3 drivers were treated with suspiciously generous tolerance by the stewards at Monaco: Elio was no exception, and it was decided not to take any action.

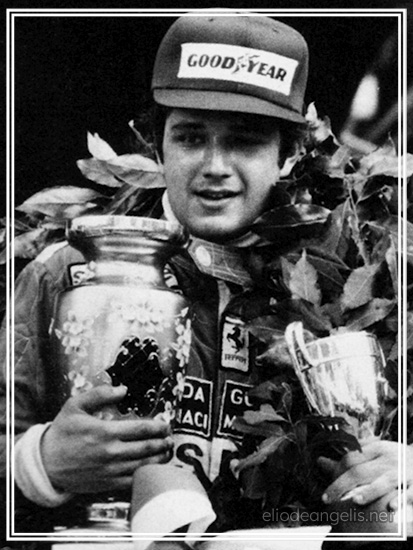

There followed a brief flirtation with Ferrari, starting with the test of a sports car intended for Le Mans (nothing came of it) and then an invitation to test an F1 car as a possible temporary replacement for an unwell Gilles Villeneuve (the Canadian quickly recovered). Elio was asked to sign some papers, although it seems not to have been a full-blooded commitment, as he told me a couple of years later. “The document I signed in Maranello wasn’t a full contract, although I was given the opportunity to test with Ferrari. I drove their F1 car on several occasions. Looking back, I think it was just a question of luck I didn’t race one of their cars. I came close in 1978: if Gilles had had one more accident, I would’ve been given his place in the team.

“In Italy, when a team is going through a bad period, there is a tendency to look at the driver before anything else. I realised that my position with Minardi was in danger, and I decided to leave. I spoke to my father about it first and he advised me, ‘You can’t do it, you have a contract,’ but I did. I knew I was taking a risk with my career, but I had to do it because I knew I’d be able to do well with an English team. So I drove one of the ICI F2 cars, and immediately I knew I’d done the right thing. But I have to admit there cannot be many 19-year-old drivers who have quit Ferrari. As I said, it was a matter of luck that it paid off. You’re always alone when you make the big decisions of life: now, fortunately, even my father agrees that what I did was right for me.”

If Gilles had had one more accident, I would’ve been given his place at Ferrari

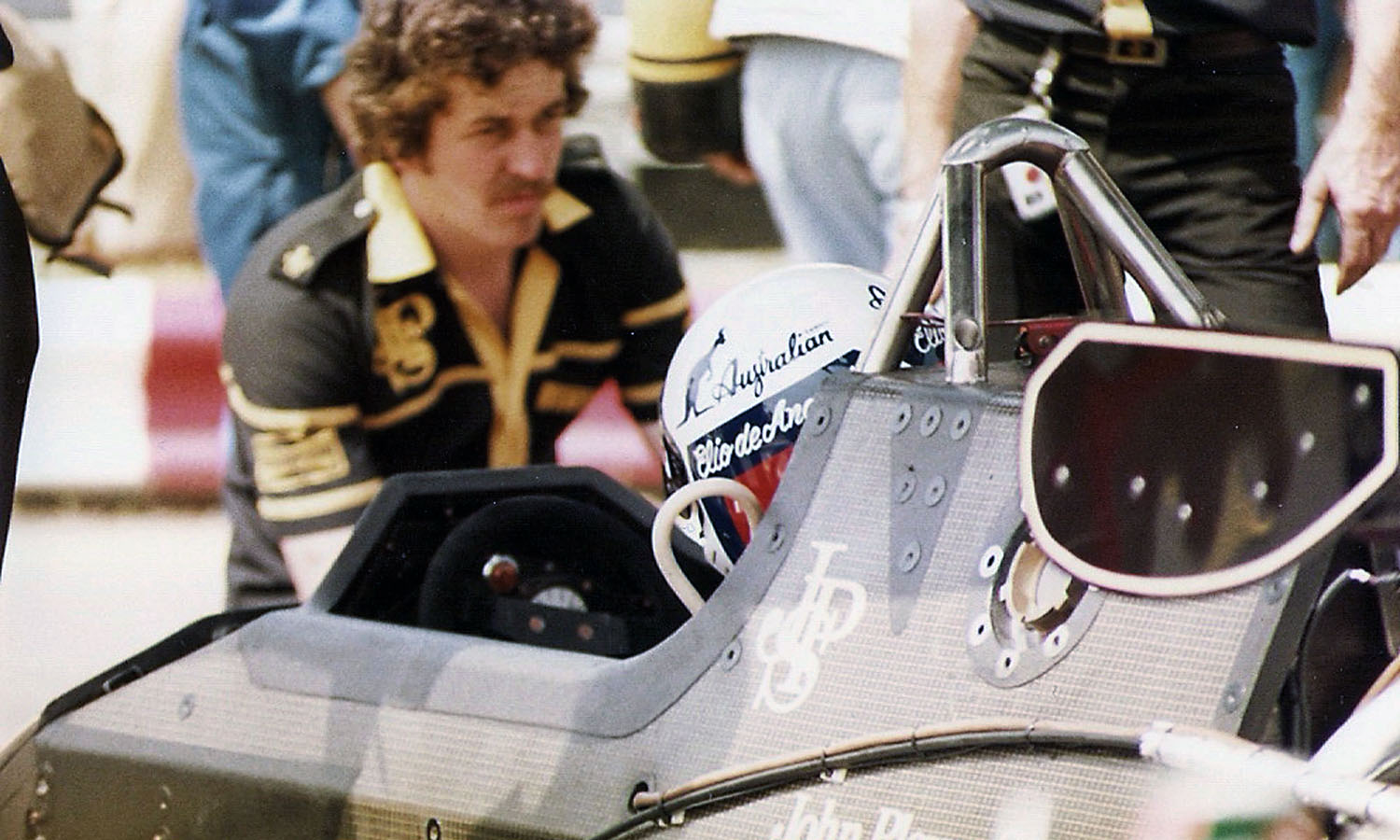

By the end of ’78 the precociously talented Roman had come to the attention of several more F1 teams, including Brabham, with Shadow inviting him to test at Silverstone in September. The first team owner to get the de Angelis signature on a contract, however, was Ken Tyrrell, although he must have known that his new recruit had not done enough in F2 to be sure of obtaining the Superlicence necessary to race in F1. Eventually the CSAI (Italian sporting authority) intervened to ensure a Superlicence was issued, allowing an agreement to be reached with Shadow, supposedly just for the first half of the ’79 season.

Still not 21, Elio was firmly on the F1 radar, although the combination of inexperience and Shadow’s outdated equipment stood in the way of hard results. Eventually team owner Don Nichols took advantage of the fact that Elio was behind with his payments to push him into a long-term deal as a paid driver. The first eight races still had to be paid for, though, for which Elio had to borrow money from his father. He made sure that those close to him were aware he’d been punctilious about repaying it, which he was eventually able to do from his Lotus earnings.

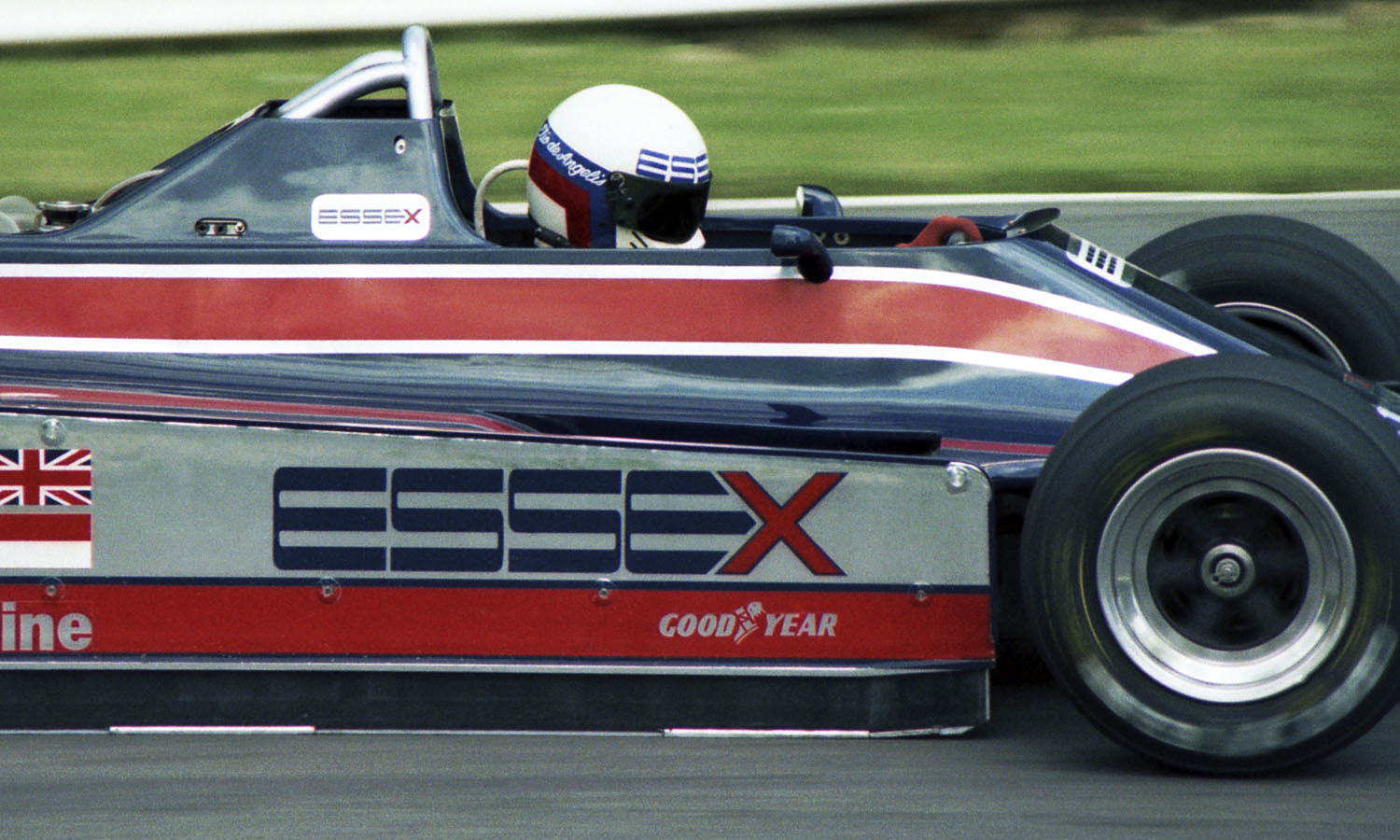

The hurriedly concluded Shadow deal turned out to be legally inconvenient when Colin Chapman, in search of a replacement for Carlos Reutemann, organised a test at Ricard at the end of 1979 in which five young drivers — Elio, Nigel Mansell, Stephen South, Eddie Cheever and Jan Lammers — were invited to take part. Even though Elio was quickest on the day, Chapman favoured the two Brits. But he had recently done a big-money sponsorship deal with the American-born oil trader David Thieme — a self-publicising rascal with seemingly limitless resources — and Thieme liked the idea of employing the debonair de Angelis with his tanned good looks and sophisticated tastes. Chapman could hardly refuse, having already been dropped by long-term sponsor John Player and having rejected an extension of a deal with the Martini & Rossi liquor giant.

Happy though he was to sign up with Lotus, Elio found himself involved in two High Court actions at about the same time, the first brought on his behalf against Tyrrell, who was ruled to have offered a contract in bad faith, and the other brought against him by Shadow, whose contract Elio had signed in equally bad faith. Chapman generously offered to help resolve the Shadow suit but may not have mentioned that the costs and damages would be deducted from Elio’s retainer.

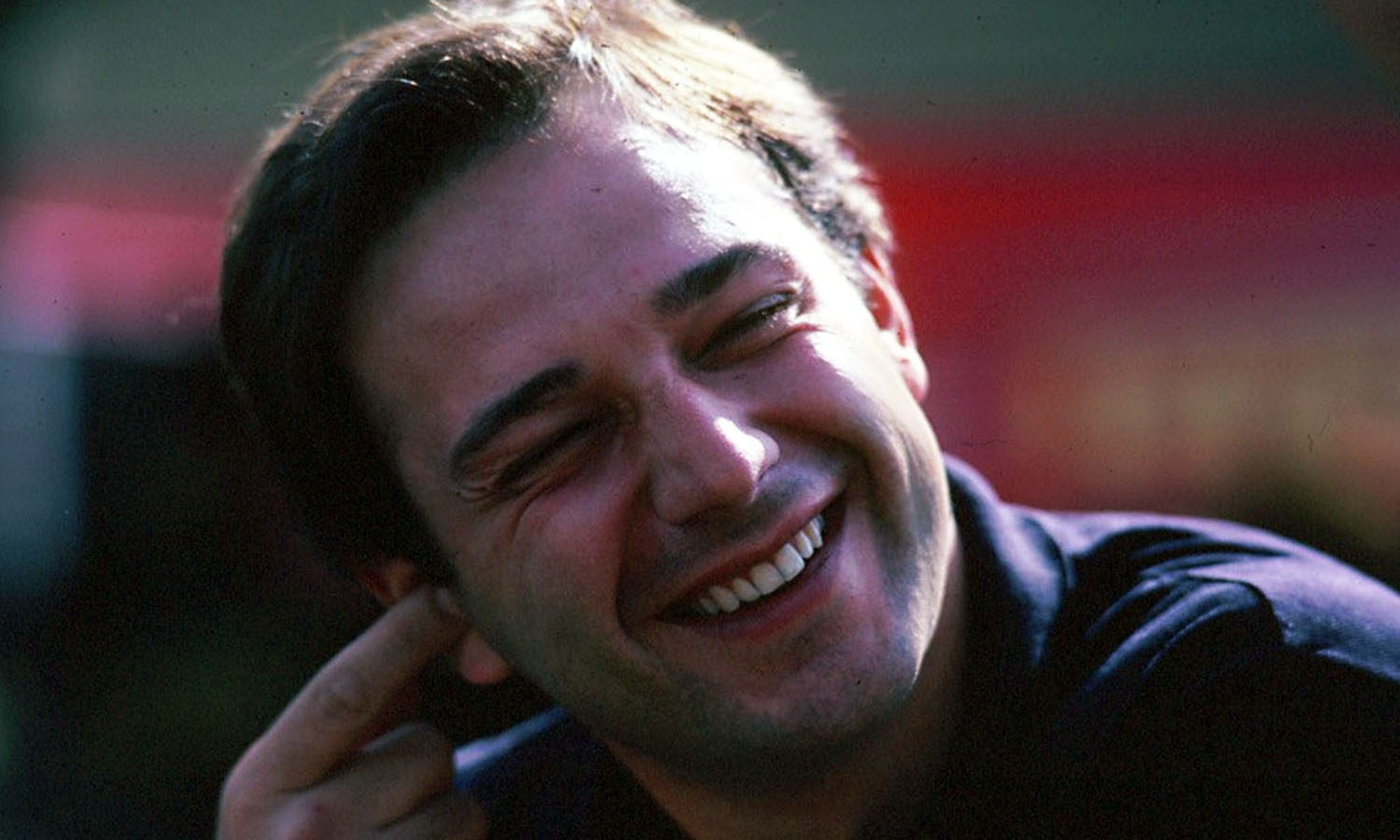

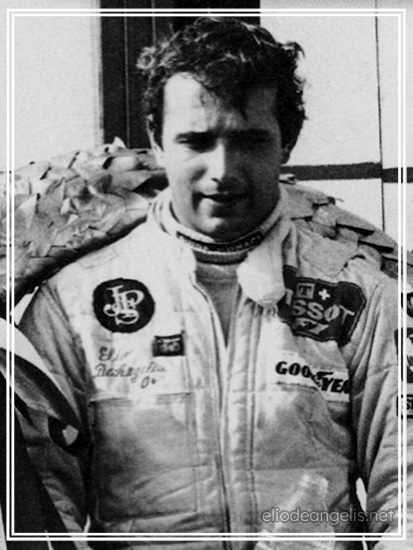

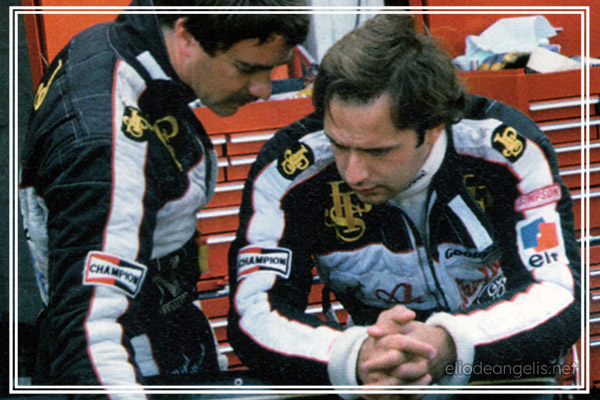

Astutely, Elio persuaded Stepney to join him in the move from Shadow to Lotus. “It was the right choice because we were the same age and both starting our careers,” Nigel recalls. “He was a likeable guy because in spite of his wealth he was pretty down to earth. He had gifts that others didn’t; he had charisma and style. He was spoiled, of course, and that allowed him to get into areas other drivers couldn’t because they didn’t have the money to do it, but he could also play the piano beautifully, which is a natural gift. He had a delightful attitude and a natural boyishness that anyone would find attractive.

“His results with Shadow in ’79 hadn’t been too bad — we’d finished fourth at Watkins Glen in difficult wet/dry circumstances, which was magic. He didn’t have to work at his driving; he was naturally gifted. But it wasn’t just as a driver that he was talented — he could do other things, like cooking. He wanted to be part of the team, so he’d prepare meals for 12 of us at the factory, using an old stove and ingredients he’d brought from Italy, just to rustle up lunch for the crew. When you’d been treated to something like that, a great relationship was the result. It also got rid of that ‘rich kid’ image you might have had of him. As did the piano playing…”

The Lotus move would prove to be inspired. Not only did Chapman warm to his new driver, there was an instant bond between Elio and Mario Andretti, who was 18 years older than his new team-mate. “As two Italians together it was almost a father-son relationship,” says Stepney. “At races, he and Mario would share a rental car. You don’t see anything like that today. Mario really nurtured him. Colin liked Elio’s style, too — he was pretty flamboyant himself, of course — and they had a good relationship which fed through the whole team.” I once asked Elio about the tips Mario had passed on to him:

“There are lots,” he said, “but the one I particularly remember was the advice he gave me about slipstreaming, how to stay in the tow from another car, and how to use it. He was always teaching me something, and I’m still learning, though now from other people too.”

On a less happy note, Elio’s arrival at Lotus coincided with one of the team’s downward cycles. Andretti left at the end of 1980, to be replaced by Mansell, and at first the relationship between the two men — who came from starkly contrasting family backgrounds — was uneasy, although they later came to genuinely friendly terms.

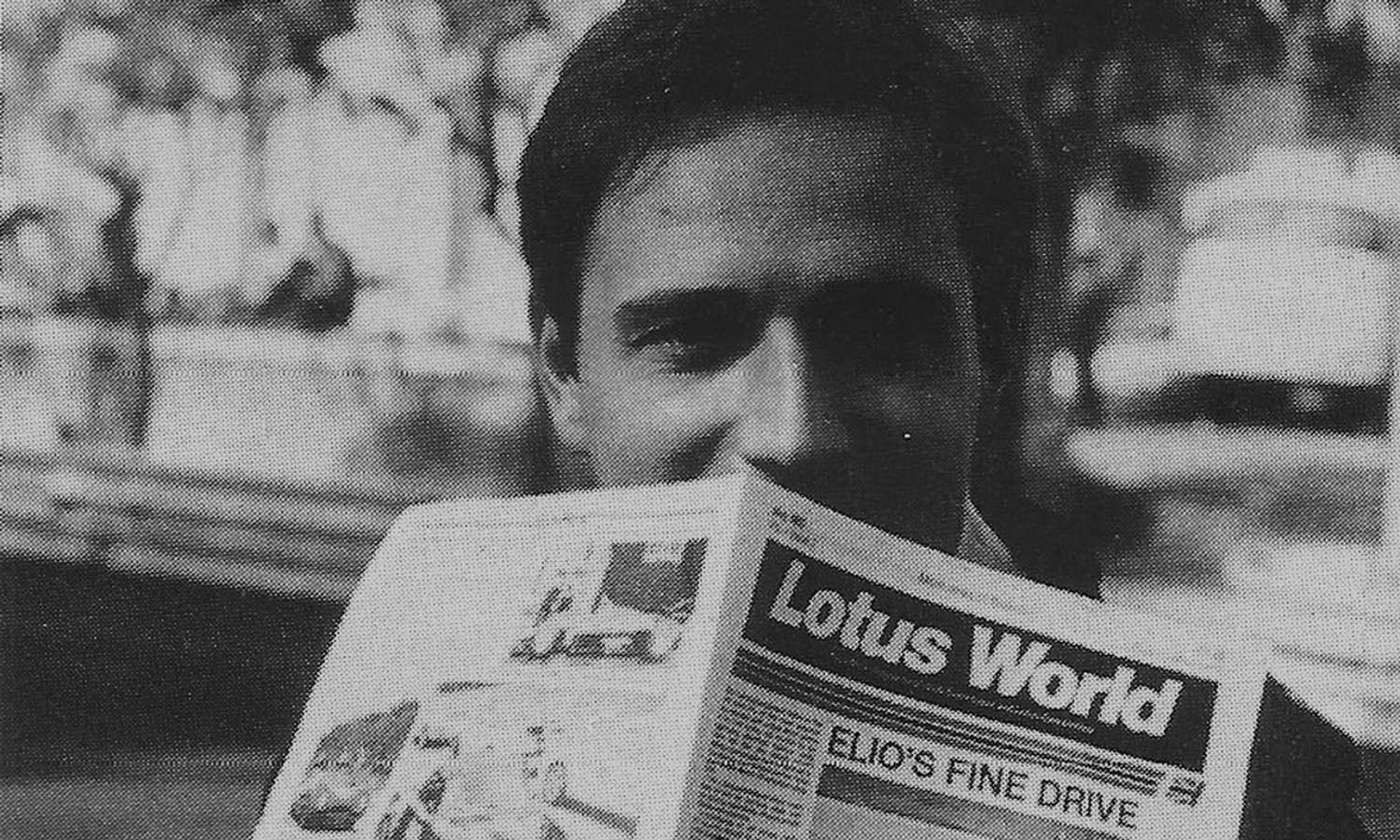

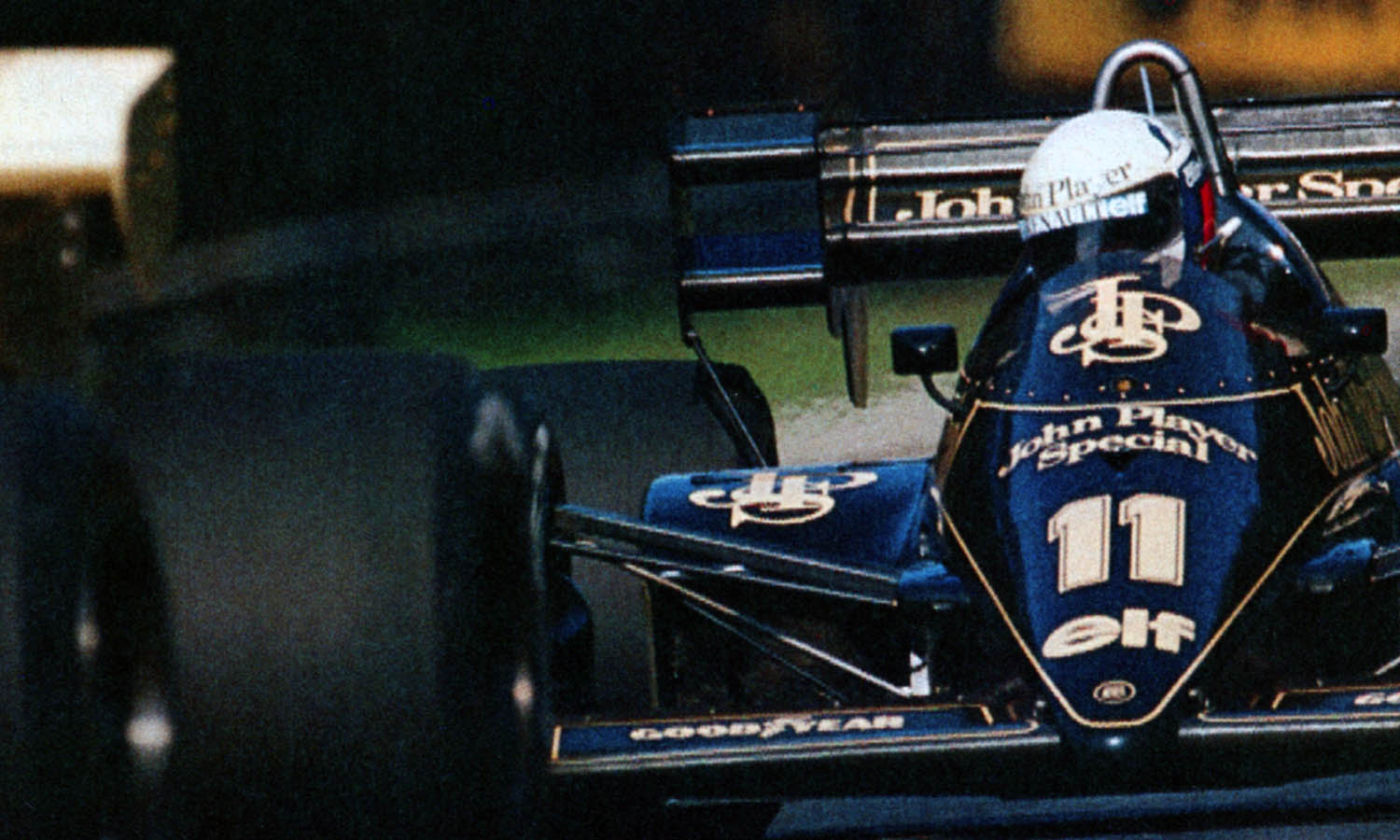

In ’81 Chapman was sidetracked by the ill-fated ‘twin chassis’ Lotus 88 project, and then the budget dried up following the dramatic incarceration of David Thieme in Switzerland. It would be Elio who lifted the team from the aftermath of that setback by narrowly beating Keke Rosberg to the line at the Osterreichring and winning the 1982 Austrian GP after all the fast turbo cars had expired. Fortunately for Chapman, John Player had just come back on board as a sponsor, and the victory — Lotus’ first in four years (and the 150th for the FordCosworth DFV engine) — restored enough of John Player’s faith to sustain its substantial sponsorship for several more seasons. Chapman had also secured Renault engines for 1983, although his sudden death in December ’82 not only meant he would never see a Lotus-Renault in action, but also raised doubts about the team’s ability to survive without him.

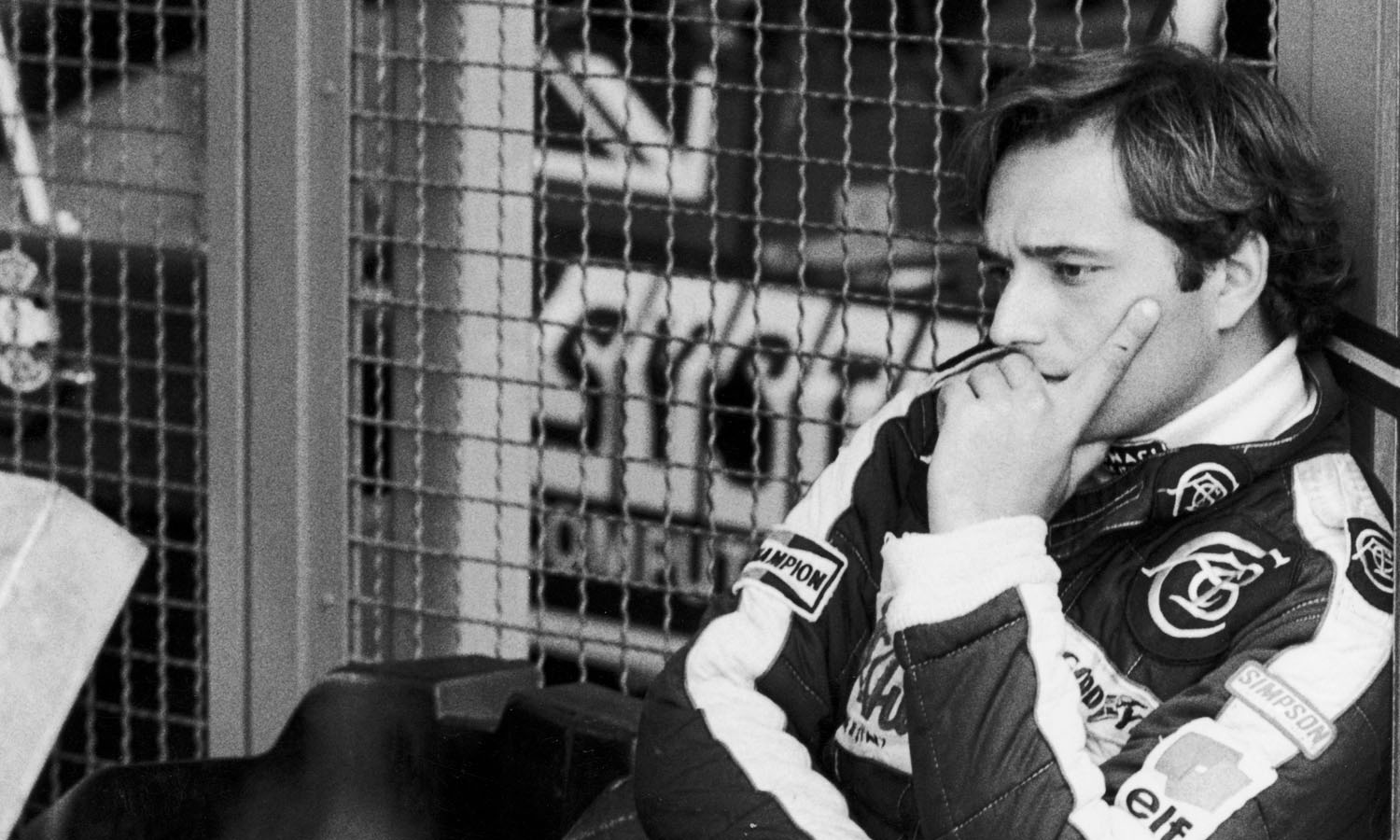

Now under the management of Chapman’s faithful lieutenant, Peter Warr, Lotus started 1983 with the gruesomely bulky 93T and inconsistent tyres provided by a new supplier, Pirelli. Warr’s commendably rapid response to the disaster of the 93T was to snap up Gerard Ducarouge as chief designer. Although the team would build three new cars in one year, by ’84 its technical progress had transformed it into the only constructor capable of challenging the red-and-white McLaren-TAG steamroller. Only a string of mechanical failures deprived de Angelis of an opportunity to vie for the title, but Warr wasn’t satisfied. He had seen the future, and it was called Ayrton Senna.

At the end of ’84 he prised the Brazilian rather clumsily out of his obligations to Toleman, and in only his second GP as a Lotus driver, on a soaking wet afternoon at Estoril in April ’85, Senna took his Lotus-Renault to a memorable victory.

Ironically, Elio’s performance in Portugal that day also deserves to be remembered, as Lotus tyre man Kenny Szymanski points out. “Even though he only took fourth, when he came into the scrutineering bay he told me the right front tyre was going down. When I went to check, sure enough the pressure was half what it should have been. That was a commendable effort, to go the distance with a half-flat tyre, completely overshadowed, of course, by Senna’s first win.”

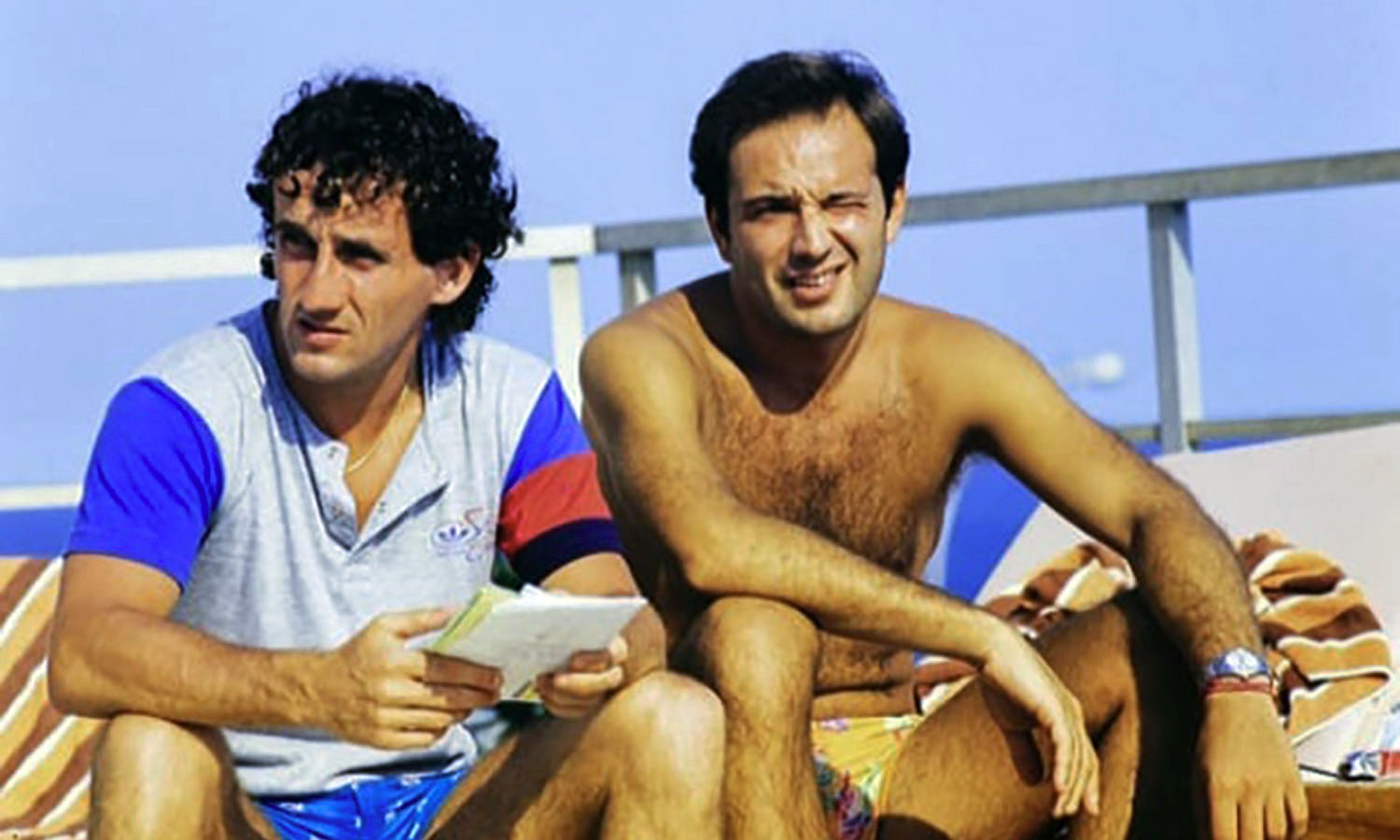

The sheer brilliance of Senna’s driving, coupled with the brutal ontrack tactics he brought with him from F3, made him the logical star of the team. But de Angelis was also picking up solid points (he’d finished third in Brazil), so when he won the San Marino GP two weeks after Estoril he moved into the championship lead. This second F1 victory, like the first, would not have happened if faster cars hadn’t been left by the roadside (out of fuel) or disqualified for being underweight, like race ‘winner’ Alain Prost’s McLaren. But then a solid third place at Monaco left Elio two points ahead in the table. If he felt this entitled him to preference over Senna, however, he was badly mistaken. As he told me later, he was made aware that he had outstayed his welcome — and he was able to pinpoint the day, even the hour, when the relationship ended.

The Jezebel, of course, was none other than Senna, and the venue was a Lotus test session at Ricard, two days after the Monaco race. “I was put on one side by Lotus,” he said. “Starting right then, all they could think about was Senna. There had been some criticisms of the way I had been driving, because I’d been more cautious than Ayrton. But when I got to the circuit they allowed me on the track just to do three laps. Imagine, on the day that I was leading the World Championship, I was left to trundle round like some new kid on the team.

“It was that night, when I left the circuit, that I made up my mind to leave Lotus. From that moment on, as far as I was concerned Lotus was a chapter in my career that had been completed. I didn’t want to be treated like that ever again.”

His sense of rejection was all the more acute because he felt that Senna, for all his undoubted ability and speed, had acted in a fashion that was less than responsible. “I knew from the start that it was going to be a difficult year. I knew he would be a difficult person. I admired his determination, and he is very determined — maybe too much. I felt he found it necessary to show off his ability: even with the success he had with Toleman the previous year, he was desperate to show he had something more. Like the Arabs say, ‘It is written’. There is something strong inside his mind: sometimes it is good for him, sometimes it is very bad. Ayrton became a protege to Peter, almost like a son, his own discovery. But he is very quick, I must say.”

There was a feeling at Lotus in 1985 — which Warr never evoked in so many words — that Elio had become something of a plodder, less motivated than he should have been in comparison with his brilliant young team-mate. Elio maintained that he, too, had once indulged in the sort of risks Senna was now taking, and that the time had come to concentrate on consistent points-scoring. “As far as motivation is concerned, I have much more now than when I started,” he insisted. “Now I know exactly what I want: I’m not doing this just for the pleasure of driving in F1. That pleasure is what my team-mate has been enjoying.”

I know what I want. I’m not doing this just for the pleasure of driving in F1

The season did not finish happily. With the McLaren-TAG juggernaut picking up momentum, so Elio’s commitment to himself and his team proved increasingly fragile. As the year progressed, Senna hammered home a total of seven pole positions and scored a second win, in Belgium. Only once, in Canada, was Elio able to summon up the will to beat him, which he did with a resounding pole that left Senna powerless to respond.

In the race, though, the pole winner was fifth. As if to mark the passing of the baton, Senna, unhappy with the service he was getting from his crew, somehow managed to wangle the transfer of Stepney and two other mechanics from Elio’s car to his. At the end of the season, at Kyalami, the Lotus team-mates tangled in the race: “I was so angry,” said Elio, “that I almost came to blows with him in the pits afterwards.”

Although he had seriously considered retirement, Elio responded enthusiastically to the offer of a place at Brabham for 1986 and a chance to drive Murray’s ultra-low-profile BT55. Plagued by an almost horizontal driving position and shortcomings in the lubrication of its lie flat’ BMW engine, the car was a step too far. In his four outings as a Brabham driver, Elio never completed a race distance. His funeral was attended by hundreds, including none other than a tearful Senna.

So just how talented was de Angelis? Stepney pulls no punches: “Elio sometimes outperformed Senna which not many people could do, certainly not in qualifying, like the time Elio outqualified him in Canada. But in the race, as soon as tyre wear and other factors started to make things difficult, Senna would become stronger in the later stages, as his ability to manage the car came into effect. To maintain any advantage he had over Senna, Elio would be using his car to the maximum and destroying his tyres. Even so he did occasionally outshine Senna, which shows he had the ability, but he wasn’t able to demonstrate it on a consistent basis.” Maudlin though it may seem now, Elio had elegantly justified his choice of career to an Italian journalist:

“I was concerned with knowing who I was,” he declared. “I wanted to have a life of my own, not simply [to be] the product of a certain family or a certain class. You have to build your own life. When you’re young, there is no happy medium, there are two distinct sides: black and white. Never any grey. I thought the sport was like that, and I’d be able to express myself within it.”

So it would be. Motor racing has never been anything but a harsh discipline. Without it, though, the world would not have heard of the gentle and talented Elio de Angelis. Many of us still miss him.

© 2011 Motor Sport Magazine • By Mike Doodson • Published here for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended