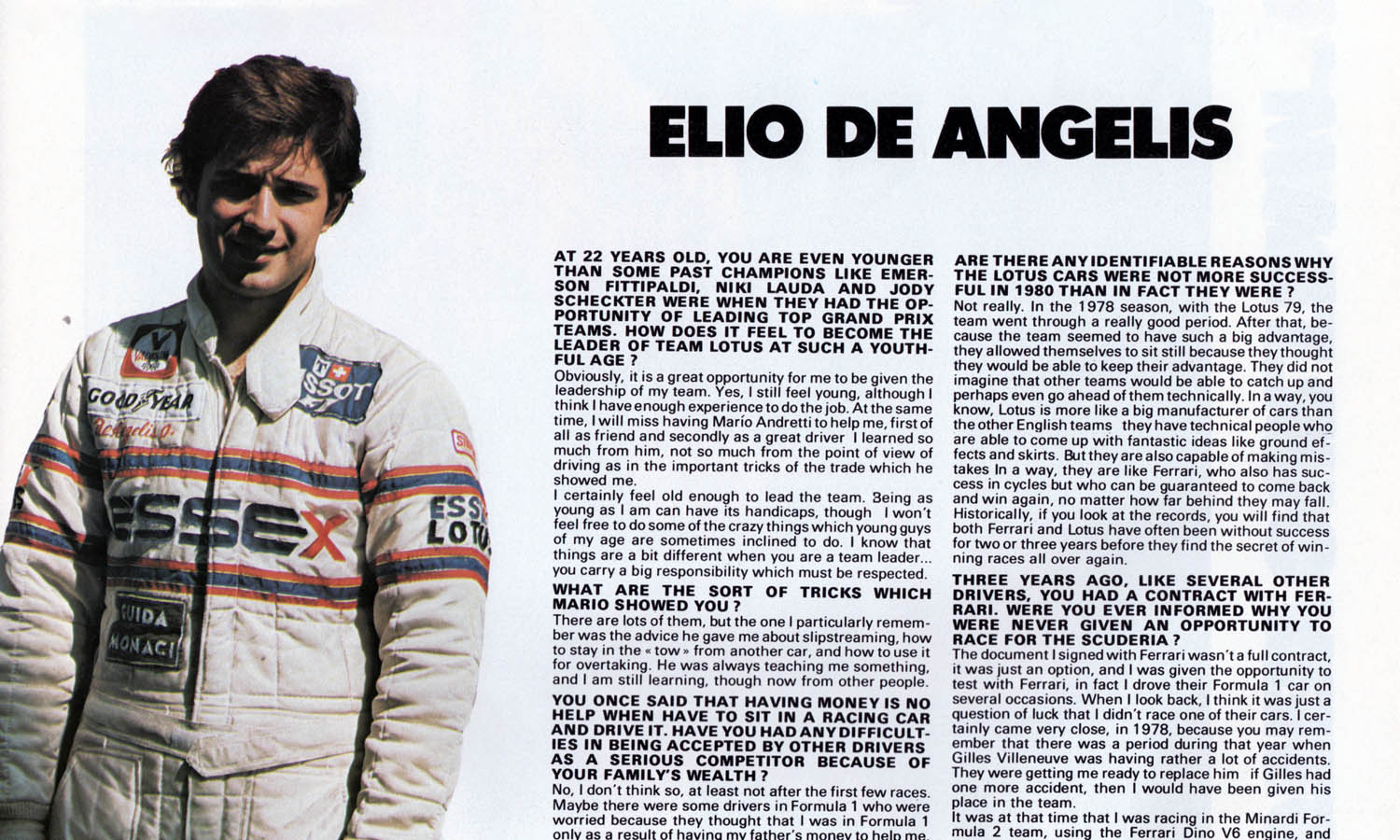

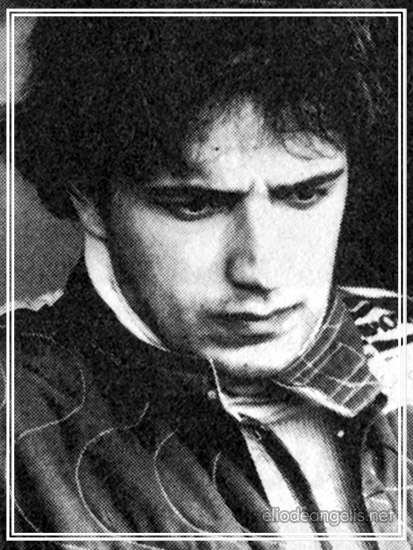

WERE it not for the inevitable conflict between youth and parental ambitions, Elio de Angelis might be internationally regarded as an accomplished classical pianist rather than team leader at Lotus. His parents steered him towards that noble musical instrument from the age of eight, but a natural reluctance to comply with their wishes saw him abandoning it a short while later.

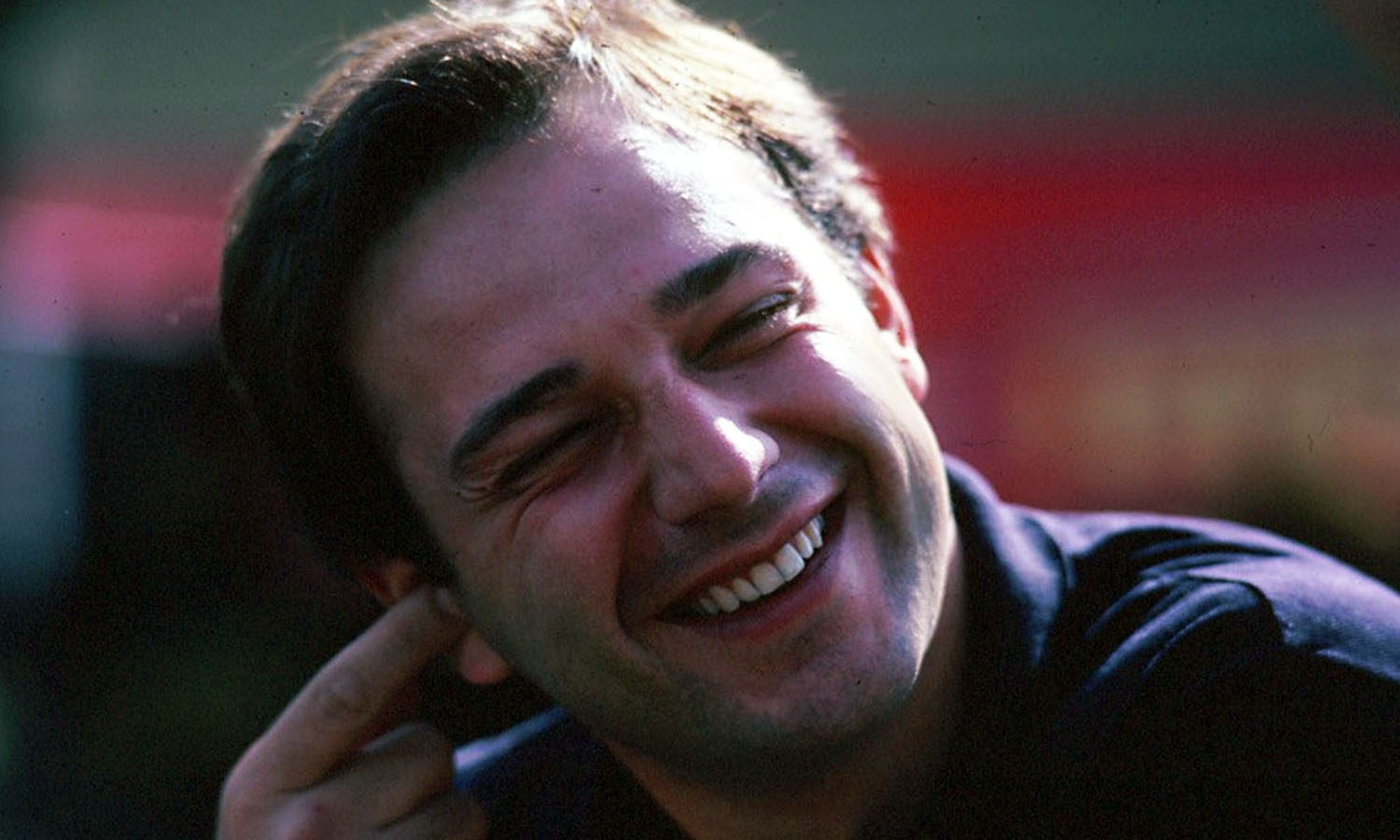

“Then, about three or four years afterwards – when I didn’t have to do it, I took it up again for pleasure…” Elio’s eyes twinkle with amusement when he openly recounts this tale. What he keeps to himself, with impressive modesty for one so youthful in the world of motor racing, is the fact that he’s such a capable pianist that there is every possibility that a commercially produced long playing record of his work will be marketed in 1981…

Born with the proverbial silver spoon in his mouth as the son of a wealthy Roman building contractor, Elio de Angelis made up his mind from an early age that he should carve his own niche in the world. Father, Giulio de Angelis, actually raced cars briefly before turning to the specialised, spectacular world of offshore powerboating, an international sport requiring the sort of bankroll he was quite capable of providing.

“My father had three races and two crashes”, grins Elio with glee, “that’s why he stopped – or rather, why my grandfather stopped him. He competed with a Lancia Aurelia in 1951 or 52. I think it was. My mother has shown me a photograph of the car upside down in a ditch!”

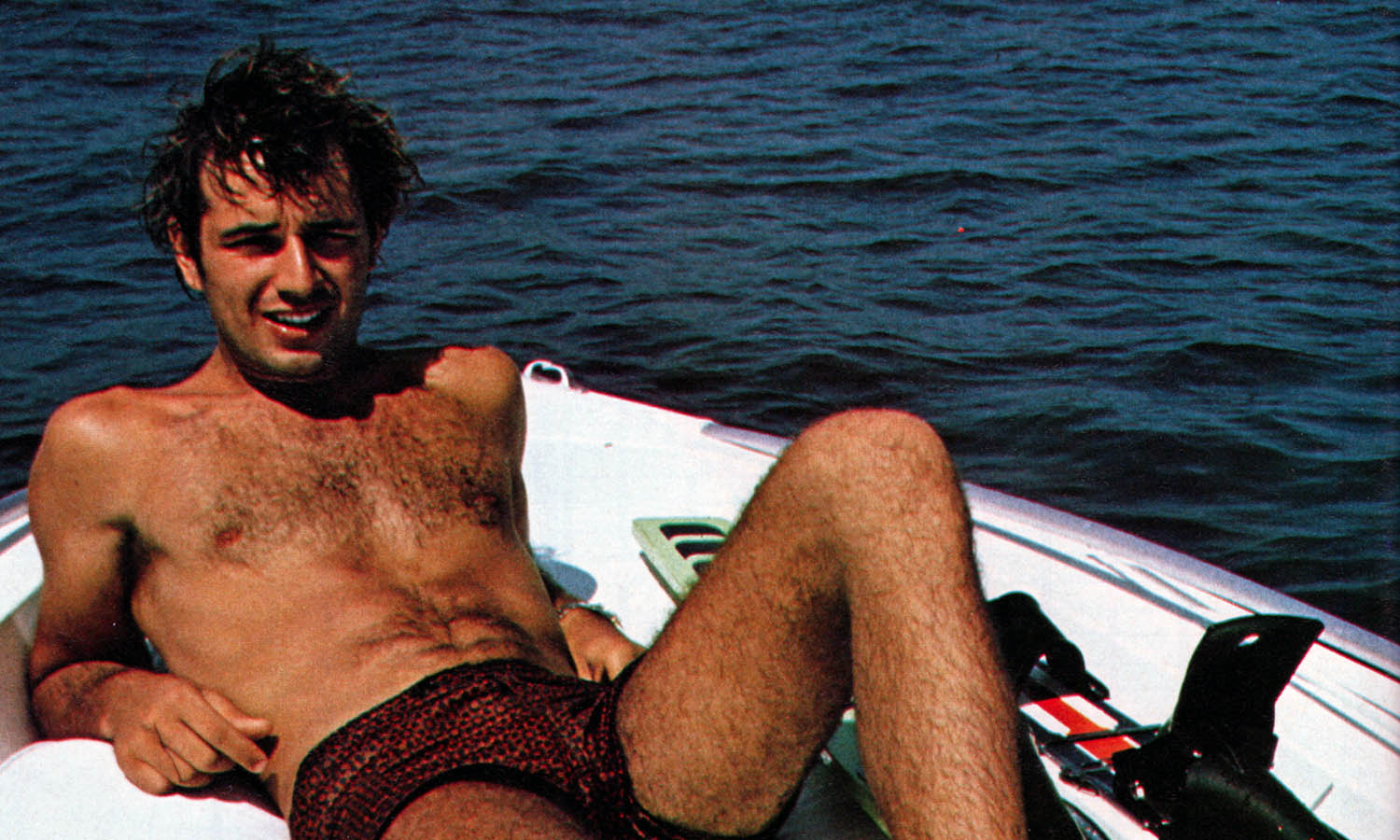

In the offshore powerboating arena, de Angelis senior was far more successful. In 1974 and 75 he was European Champion and made a big bid to take the World title in ‘74, “although it proved too expensive.” The crown that year went to his arch-rival Italian Franco Bonomi. Long before he turned his hand to car racing, young Elio was crewing for his father in the cockpit of his Mercruiser V8 powered 36-foot Cigarette craft, attracted by the speed and excitement of the sport. “I’d been his throttle man in the Cowes-Torquay-Cowes in 1974 and we were leading comfortably when we broke down” recalls Elio, “and the following year I was given the chance to drive one of the boats on my own in the Naples event.* We were leading, would you believe, but the power assistance to the rudder broke and I was trying to juggle the throttles because the guy I’d got with me wasn’t sure of the technique. Well, one thing led to another, and we were suddenly hurtling upwards, about 50 meters into the air. I can remember it so clearly; hanging on in the cockpit as we came down straight into the water.”

Elio emerged unhurt, but he recounts with some regret that one of his fellow crew members sustained two broken legs in an accident that was highly spectacular by any powerboat racing standards!

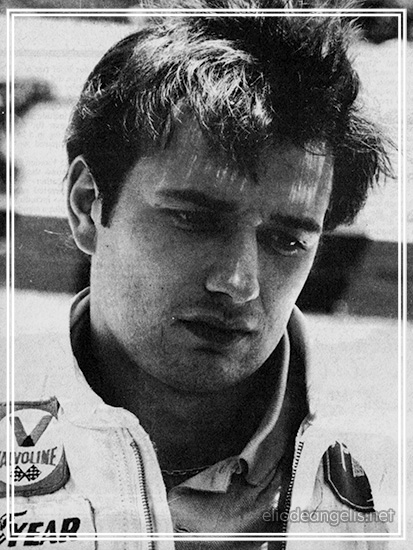

During the same period as these powerboat exploits, young Elio was developing his talents with four wheels very firmly in contact with terra firma – in kart racing. In fact, he became a member of the national Italian team alongside such luminaries as Eddie Cheever, Riccardo Patrese and the man who was to become his fiercest Formula 3 rival, Beppe Gabbiani. Elio triumphed in the 1974 Italian Championship before moving on to take the ‘75 European title and finish runner-up in the Class 1 World Championship for 100 cc karts.

By now he was hooked by a taste for motorsport. “I went down to Henry Morrogh’s racing school at Vallelunga where they’d got Formula Italia single seaters.” The trouble was that Giulio de Angelis was absolutely determined not to unduly spoil his son. He paid for the first lesson in the course, but would only pay, individually, for the subsequent eight if Elio studied hard enough on his university course.

But, as Mike Hailwood has so often said, “all the money in the World doesn’t buy talent”, and Elio’s ability in a single seater soon started to become obvious. During the winter of 1976/77 Elio was invited to test one of Pino Trivellato’s F3 Chevron 838s at both Misano and Paul Ricard. It looked as though he would be a member of that team for the following season, but it appears that Gabbiani baulked at the idea of having his Closest rival in the number two car – so Elio was out on his own. Nonetheless, the Trivellato team gave him some assistance and he showed considerable early promise with the difficult car. “My best result was second at Monaco behind Pironi, but then I felt we’d got to make a switch and I got hold of a Ralt. which was a much better machine.

I was told: ‘you’ll be in the team if he crashes in Belgium’...

Armed with the Ralt he won the Monza Lottery and with other victories at Mugello, Misano, Magione and Varano he wound up winning the Italian Championship.

Then came his debut in Formula 2. “I suppose I’d attracted a lot of attention by winning the Monza Lotteria”, reflects de Angelis, “and I was invited to drive one of the Minardi team Ralt-Ferrari V6s in the European Championship round at Misano. Well, you can imagine how I felt. Nineteen years old, driving a Formula Two car. I started from the third row and quickly worked my way into the lead. I thought “this is easy”, but the truth of the matter is that I’d got very suitable gear ratios and the Ralt-Ferrari was really good on full tanks. I must admit that I planned on staying in the lead and I didn’t take too much care when Merzario came up behind me. Bang! I pushed him off. Then Patrese – bang! He was off as well. Then Cheever. I finished third in the heat but nowhere on aggregate because I had trouble in the second heat.”

Elio came down to earth with a bump quick enough, however “I was invited to have another drive in the Ralt-Ferrari at Estoril. I crashed on the first corner”.

He admits, in retrospect, that he became a little carried away with his assessment of his own ability at this point in his career!

Despite this dawn of realisation, 1977 was a supremely successful season for de Angelis, one in which he established himself as a promising, youthful man to be watched. He’d raced against some good people. “In Formula 3 obviously Piquet was terrific, but Necchi was always competitive, and I frankly rated Gabbiani as well. He was wild, I’ll admit, but he was very fast and has a great deal of talent.”

Originally, Elio planned to continue his relationship with the Ferrari team for 1978. but the F2 project went off half-cock and Elio didn’t really know what he should do next. “The problem with being a Ferrari contracted driver is the whole atmosphere surrounding the Ferrari team. After I’d led at Misano, everybody got very excited, and I think there was a feeling that anything to do with Ferrari would win. Of course, I suspected otherwise.” De Angelis suspected that the Ralt wouldn’t be a good long-term proposition and fancied running a Chevron.

But Elio’s 1978 season was important for a couple of other reasons. Firstly, his Ferrari connections resulted in his receiving an invitation to do some testing at Fiorano. “I got the chance to drive the T2 and T3 more than 1000 kilometers and Mr. Ferrari told me there was a chance that I might be joining Reutemann in the Grand Prix team. At the time, if you recall, Villeneuve was doing a lot of crashing. After Long Beach, where he crashed while in the lead, I was told ‘you’ll be driving in the team if he crashes in Belgium.’ Of course, Gilles got everything together and finished third – despite a puncture – behind the two Lotuses at Zolder. So, that was that.”

De Angelis also had the chance of driving one of the Le Mans prepared 512BB coupés: “Really, they didn’t handle well at all. Fantastic engines, but I suspect the chassis was twisting. The brakes? Awful. I was wearing them out in twenty laps at Fiorano and they were supposed to be preparing for a 24-hour race!”

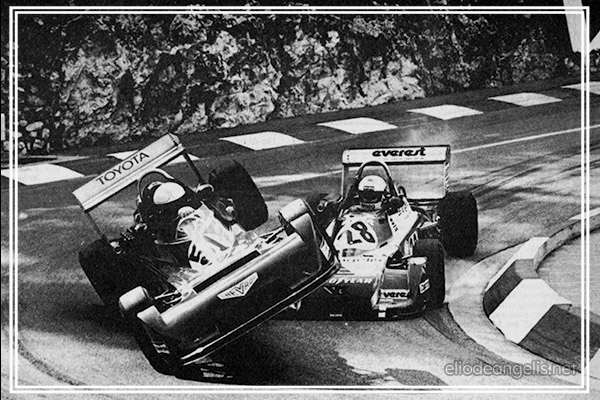

By this stage de Angelis had attracted many critics within Italy, so he needed to do something to get his name back into the headlines. So, he hired a Formula 3 Chevron and entered the Monaco F3 classic again. It was a gamble but following a much-publicised tangle with the similar car driven by Frenchman Patrick Gaillard, in which Elio literally pitched his rival out of the way at the Loews Hairpin, he won the race.

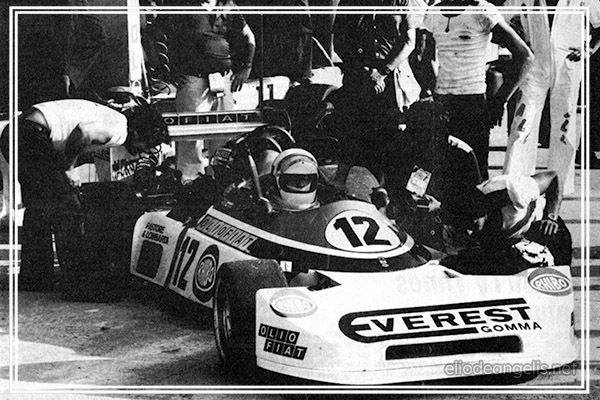

“I had to do something pretty dramatic”, he recounts, “because I was worried about the nosecone, which had worked loose. As it turned out, everything was going my way on that occasion!” Later in the summer, Elio decided on a switch to the ICI Chevron Formula 2 team, but “I had problems to start with. My car wasn’t the same as Derek Daly’s but once we got things sorted out it was very much better than that Ralt. And there’s no doubt in my mind that Brian Hart’s 2-litre four-cylinder F2 unit is an absolutely wonderful little engine. Reliable, powerful – in fact, everything you’d want from a racing engine.” However, it wasn’t until towards the end of the season that Elio settled into the ICI team. “My first good race was back at Misano – a year after my Ralt-Ferrari debut. I finished third in one of the beats and then had trouble in the second.”

Ambitious as ever, Elio by now had his sights firmly set on Formula One for 1979. He had long discussions with Bernie Ecclestone and “almost signed to drive alongside Niki in the Brabham-Alfa team when Piquet arrived with some sponsorship.” Then came the remarkable development when Ken Tyrrell signed him, only to refute the arrangement a few days later. “He said I hadn’t got the correct ‘A’ license”, Elio explains, “but that wasn’t the case at all. I had got the correct license at the time. I think he was a little embarrassed by it all.” That little matter is still being resolved in the English law courts and a decision is confidently expected within the next few months.

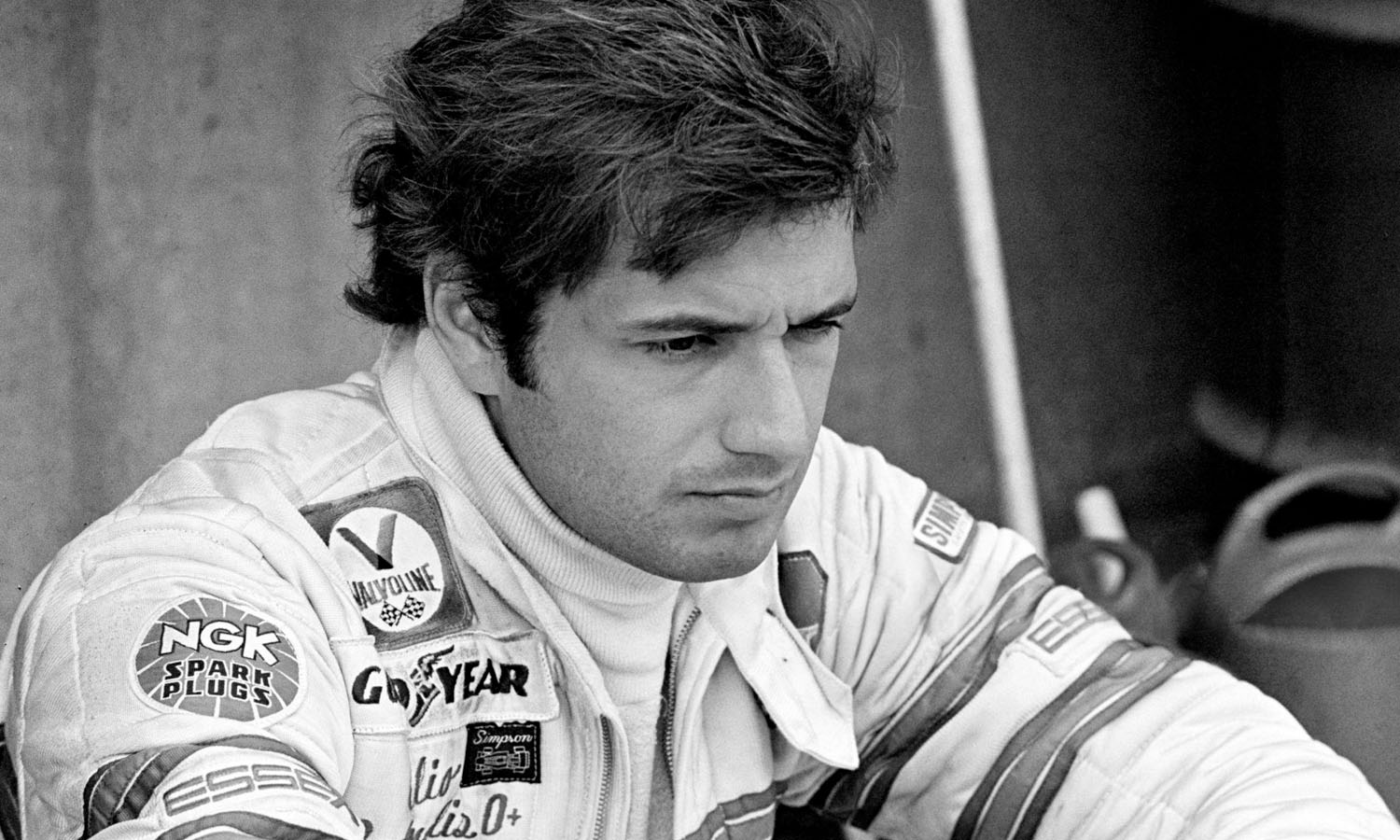

Eventually, Elio de Angelis found some sponsorship and put together a deal with Don Nichols’ Shadow organisation. Shadow themselves were badly under-financed and Elio admits that he’d only found sufficient sponsorship to keep him going for eight races. Nevertheless, with his fingers firmly crossed that something would turn up, he confidently signed his contract. In fact, he signed a deal for three years although, in his heart of hearts, he knew that he was unlikely to stay on.

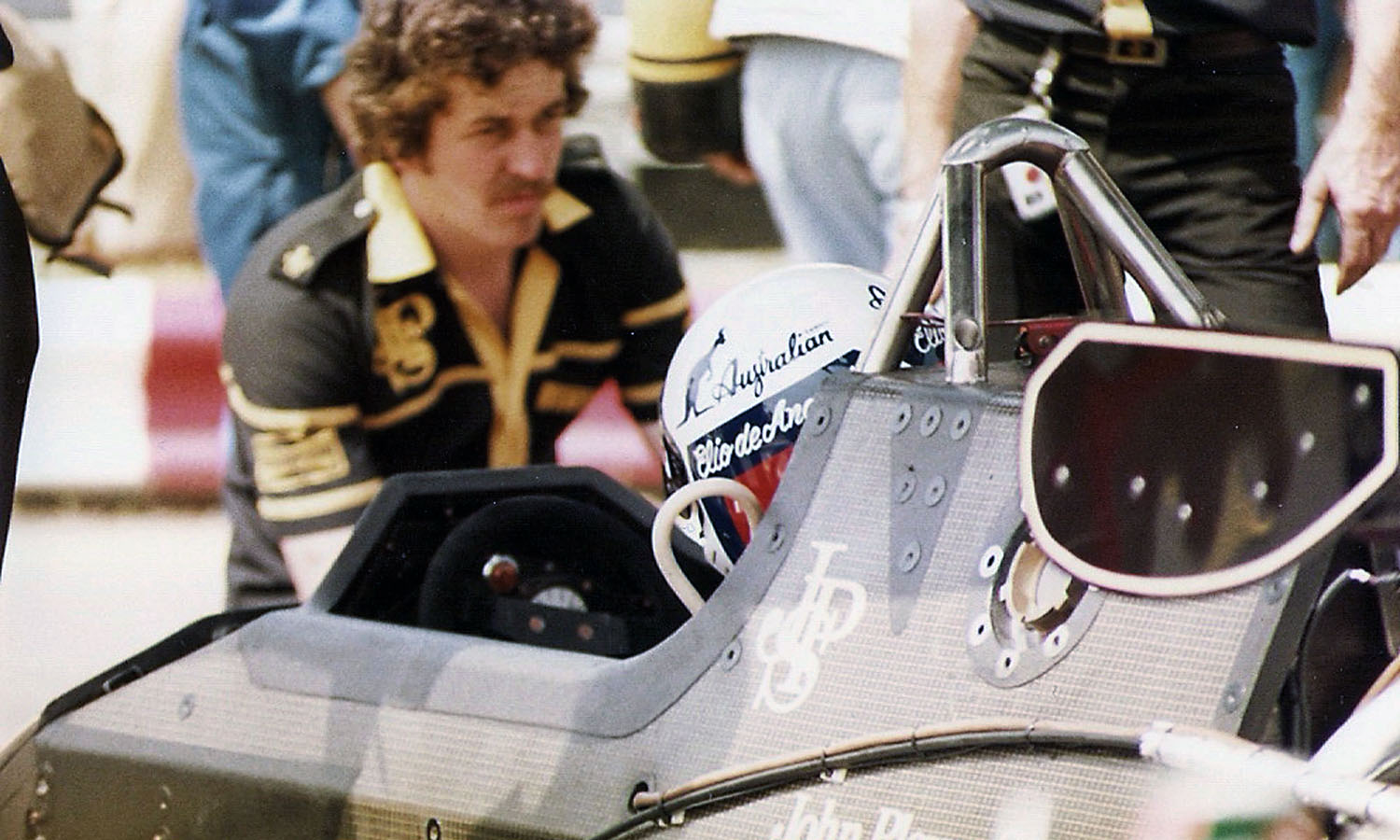

“It was absolutely essential, I thought, that I should get into Formula One. I signed the contract because there was no choice. I thought that I’d argue about it later, but meanwhile I had the opportunity to drive in Grands Prix.” Elio’s F1 debut was in the blazing heat of Argentina. He survived the pitfalls that befell many more experienced competitors and finished seventh. Not bad for a debut.

I'd like to have a crack at Indy. I think I'm crazy enough...

“That DN9B wasn’t a good car The team was short of money, and they couldn’t do much in the way of development work. The biggest problem with the Shadow was that it had too much understeer. They never got round to revising the front suspension geometry to cope with the latest rubber. I don’t think there was any circuit on which we raced at which I didn’t feel the car was understeering too much.”

There was nothing to do but go...

Nevertheless, Elio did show some promise. His best qualifying position was 11th on the grid at Silverstone for the British GP, only for the clutch to start playing up on the line. “I thought I’d be penalised, but when the car started rolling there was nothing I could do. I dropped the clutch and realised that the starter hadn’t given the signal. There was nothing to do but go as quickly as I could.”

Being amongst the established tail-end teams, Shadow rarely got hold of decent qualifying rubber. Pressure of competition with Michelin obliged Goodyear to adopt a ruthless system limiting the supply of top-class cover to the best teams. These rules provided for one set of qualifiers to be ”earned” on the first day by a single car out of the “non privileged” teams – Shadow, ATS and Ensign. On the first day of timed practice at each race there was fearful private scrap between these runners for that precious set of qualifiers. Elio recalls those contests with amusement, tinged with a touch of apprehension.

“I didn’t like that rule very much. It seemed to be a silly thing to get yourself killed for. I mean, we took some really ridiculous risks. On one occasion there was me, Lammers, Stuck and Surer, all trying like hell for that final set of tyres. Can you imagine that?”

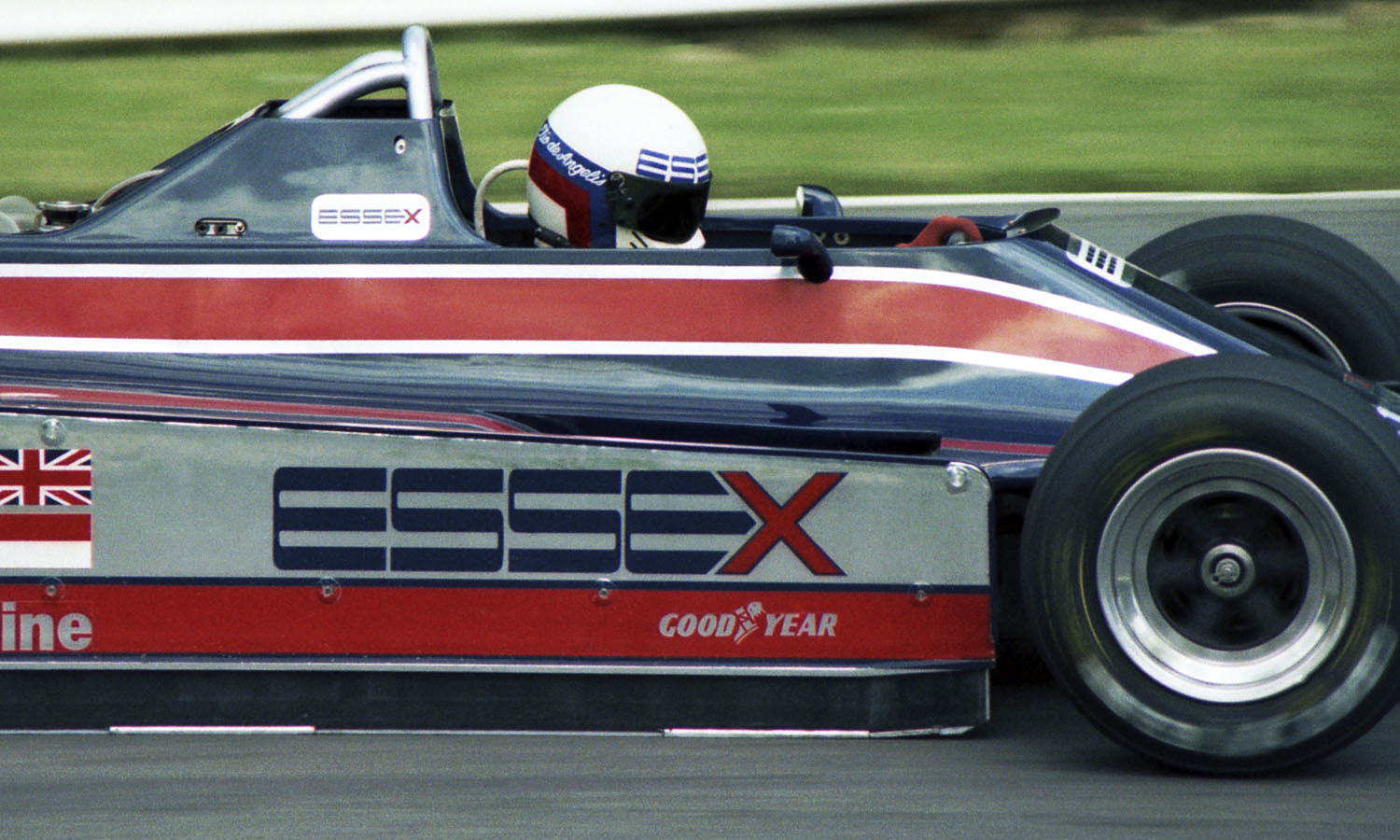

Frequently de Angelis would be the man who qualified for that set of qualifiers, but it wasn’t until the final race, the United States GP at Watkins Glen, that he scored his first World Championship points.

“The DN9B wasn’t handling too badly on that occasion”, he grins, “we’d got it set up for the wet and the understeer was only slight. But the important thing was for me to keep ahead of Stuck’s ATS as far as Shadow were concerned, for the last place in the FOCA membership lists depended on it. You should have seen the signals from the pits. They were really frantic with concern.” As it was, Elio saved Shadow’s bacon – albeit temporarily – by coming home fourth, one place in front of Stuck.

... all trying like hell for that final set of tyres.

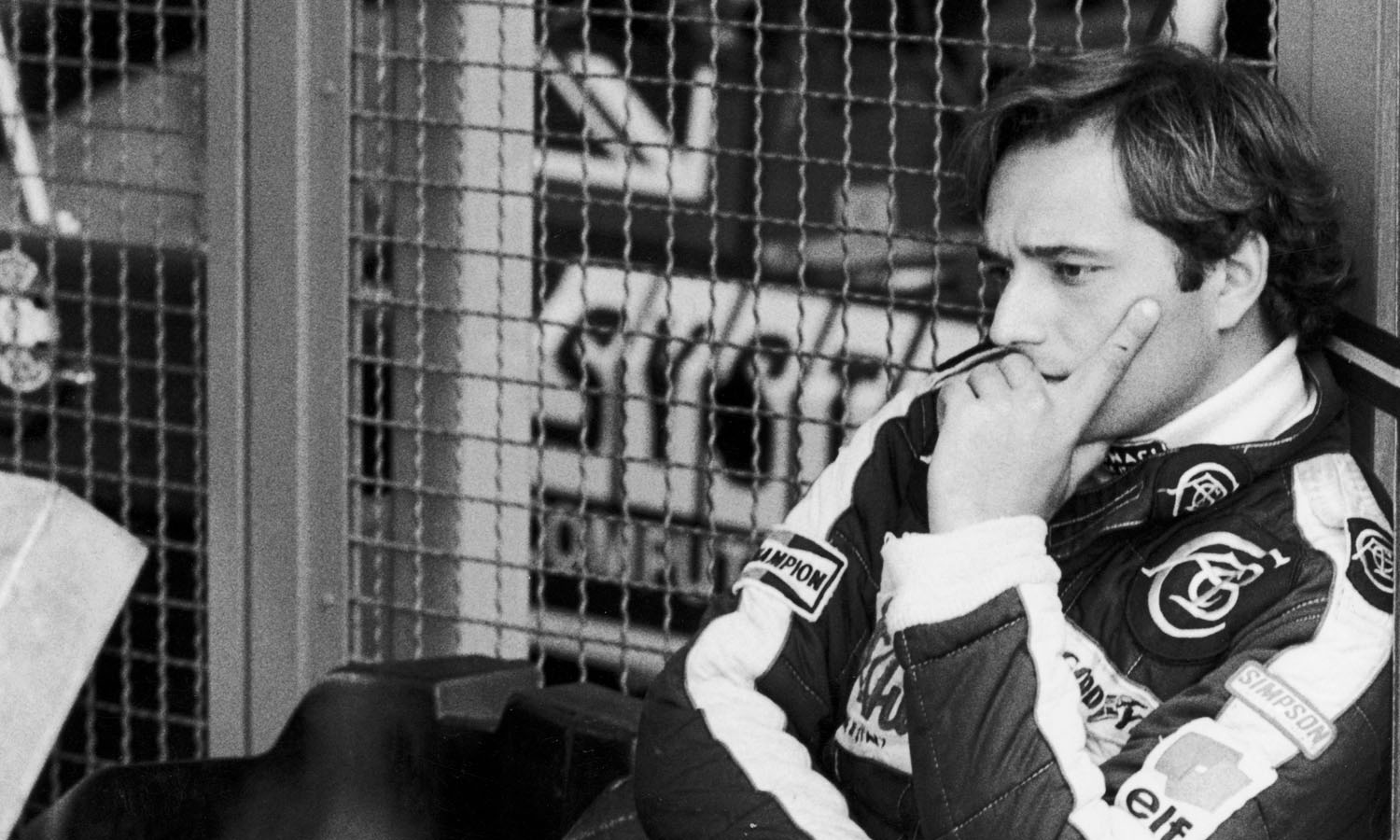

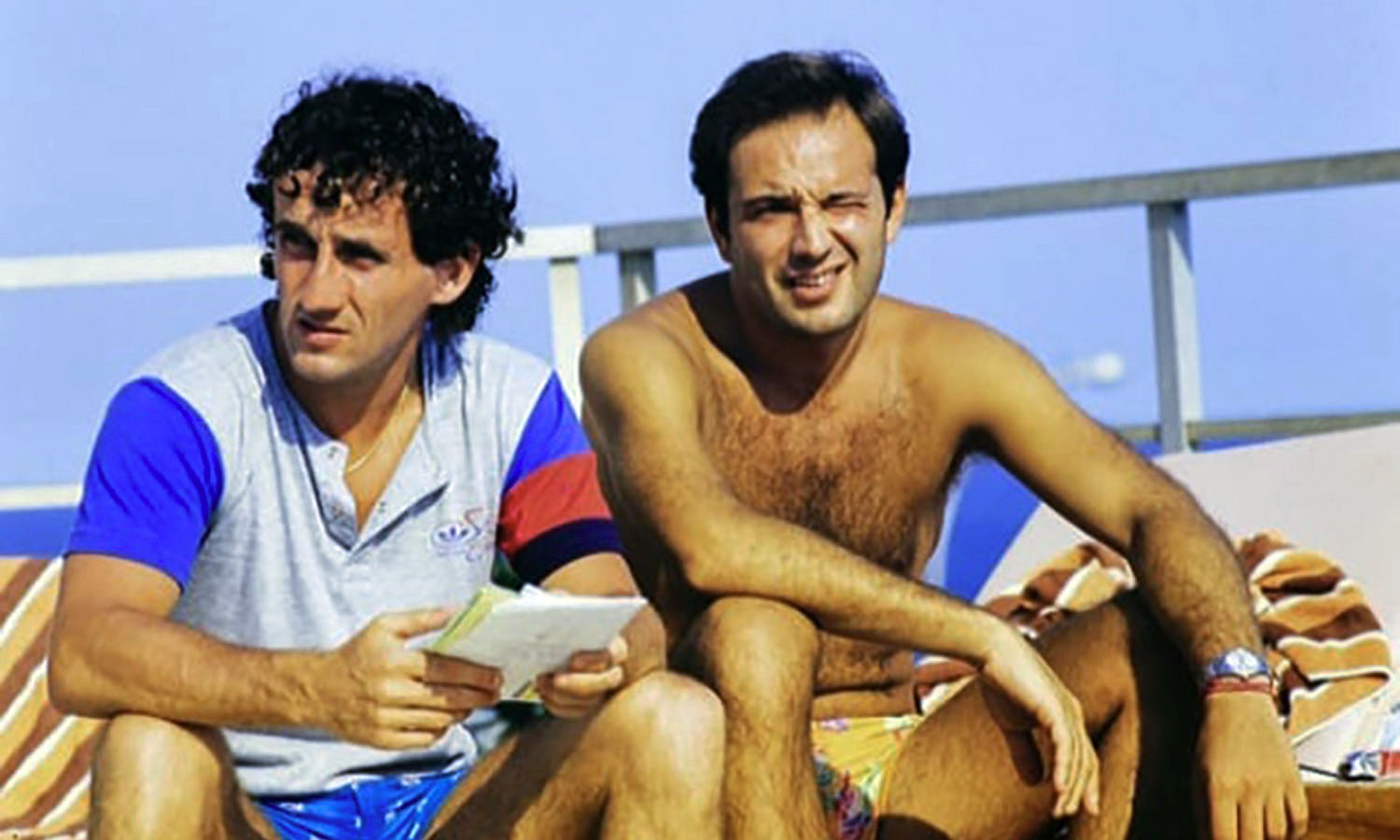

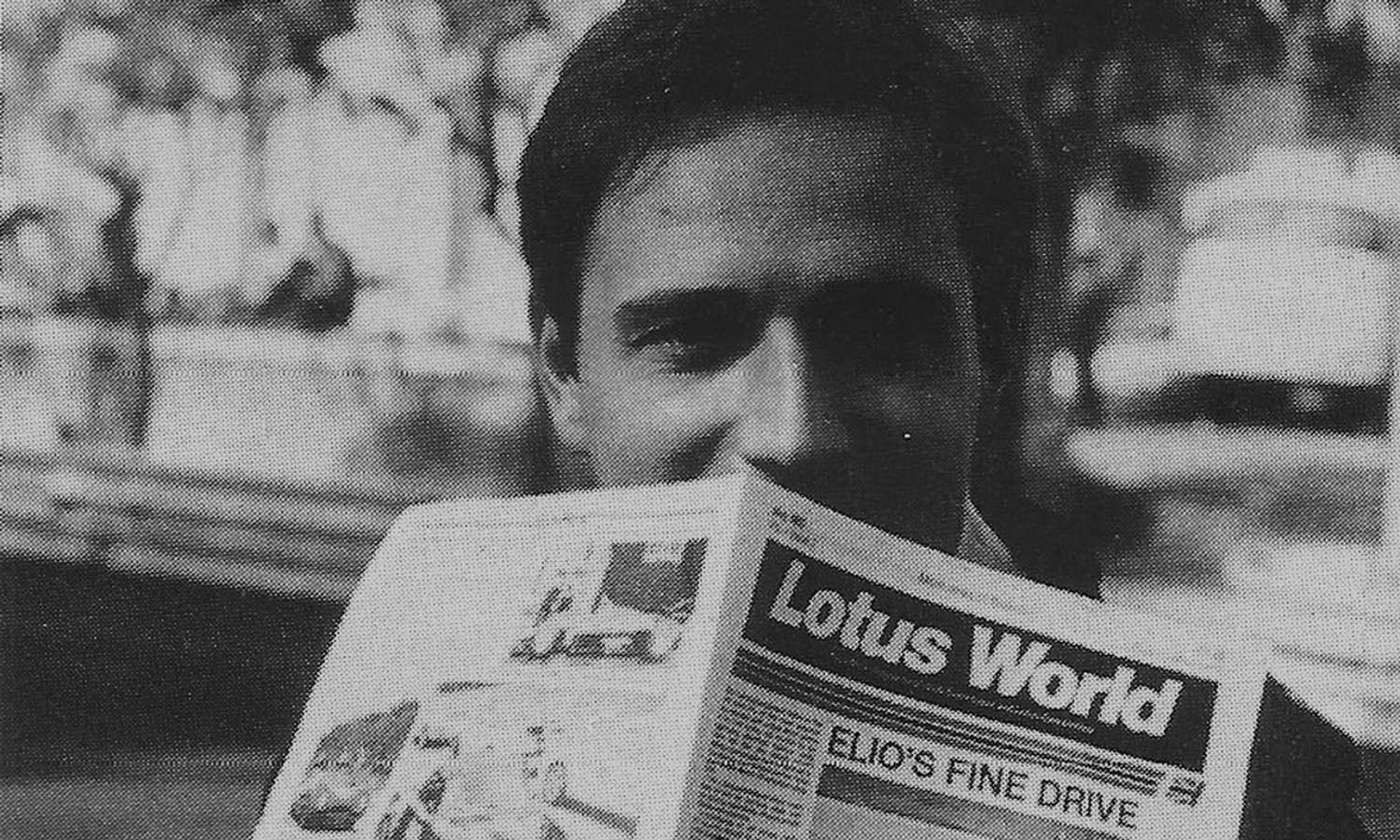

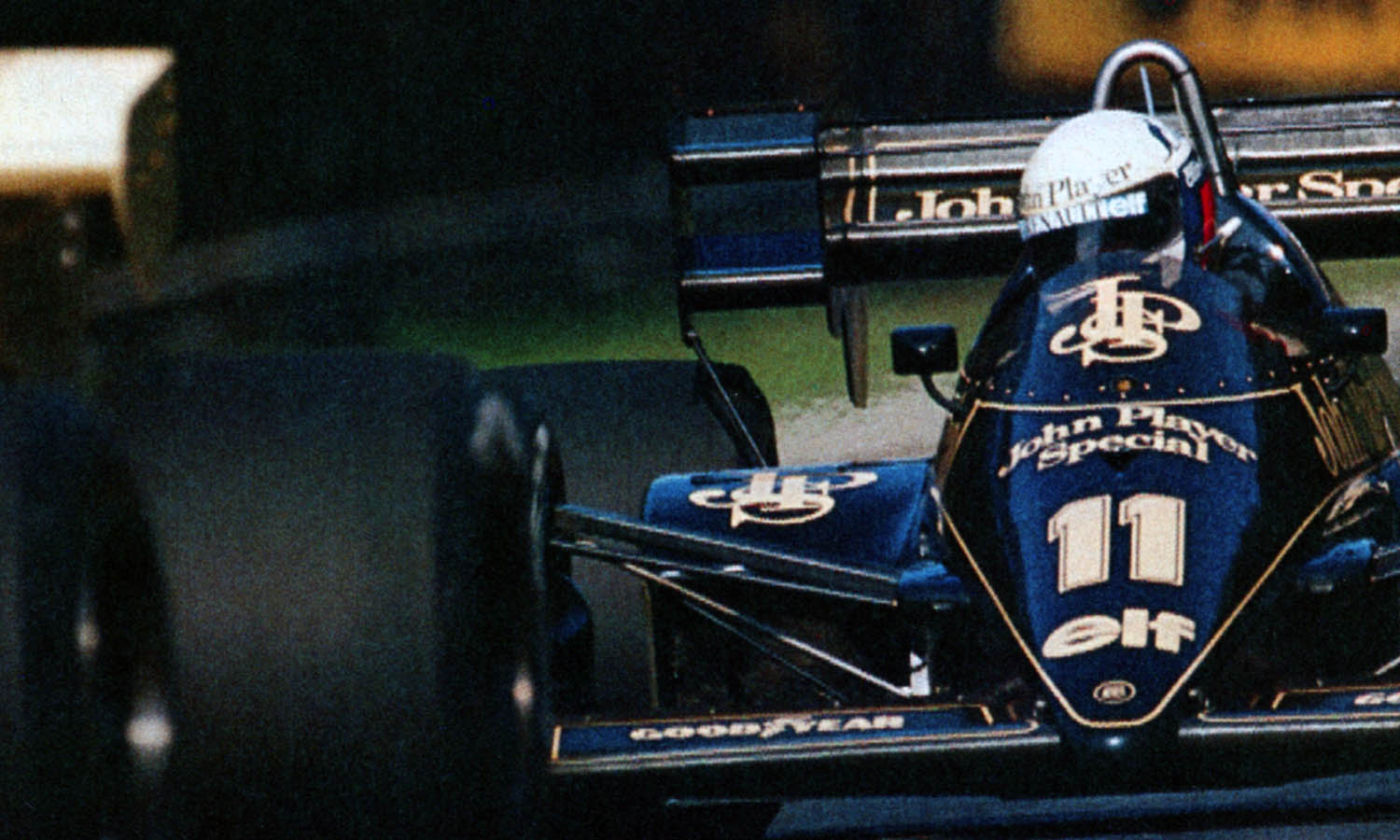

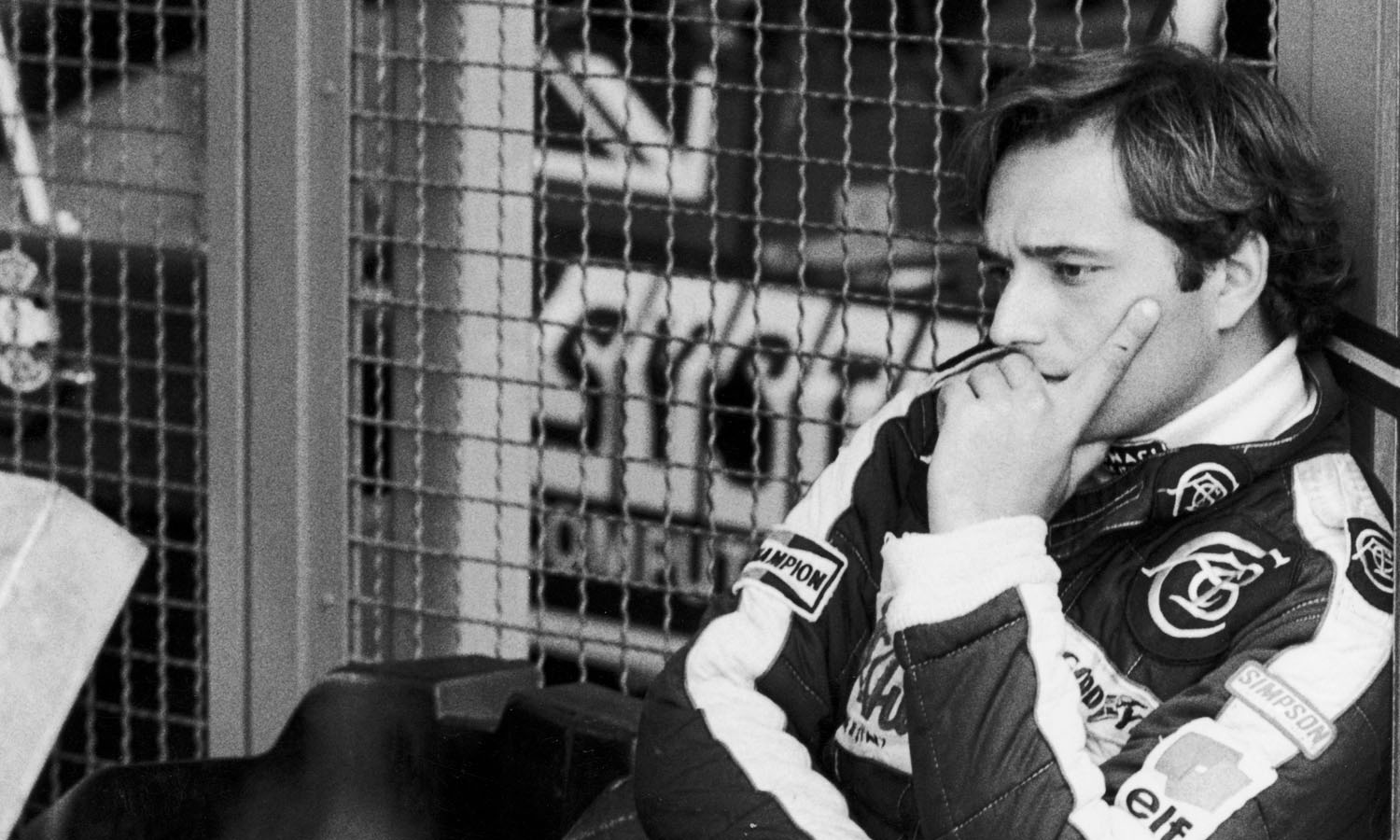

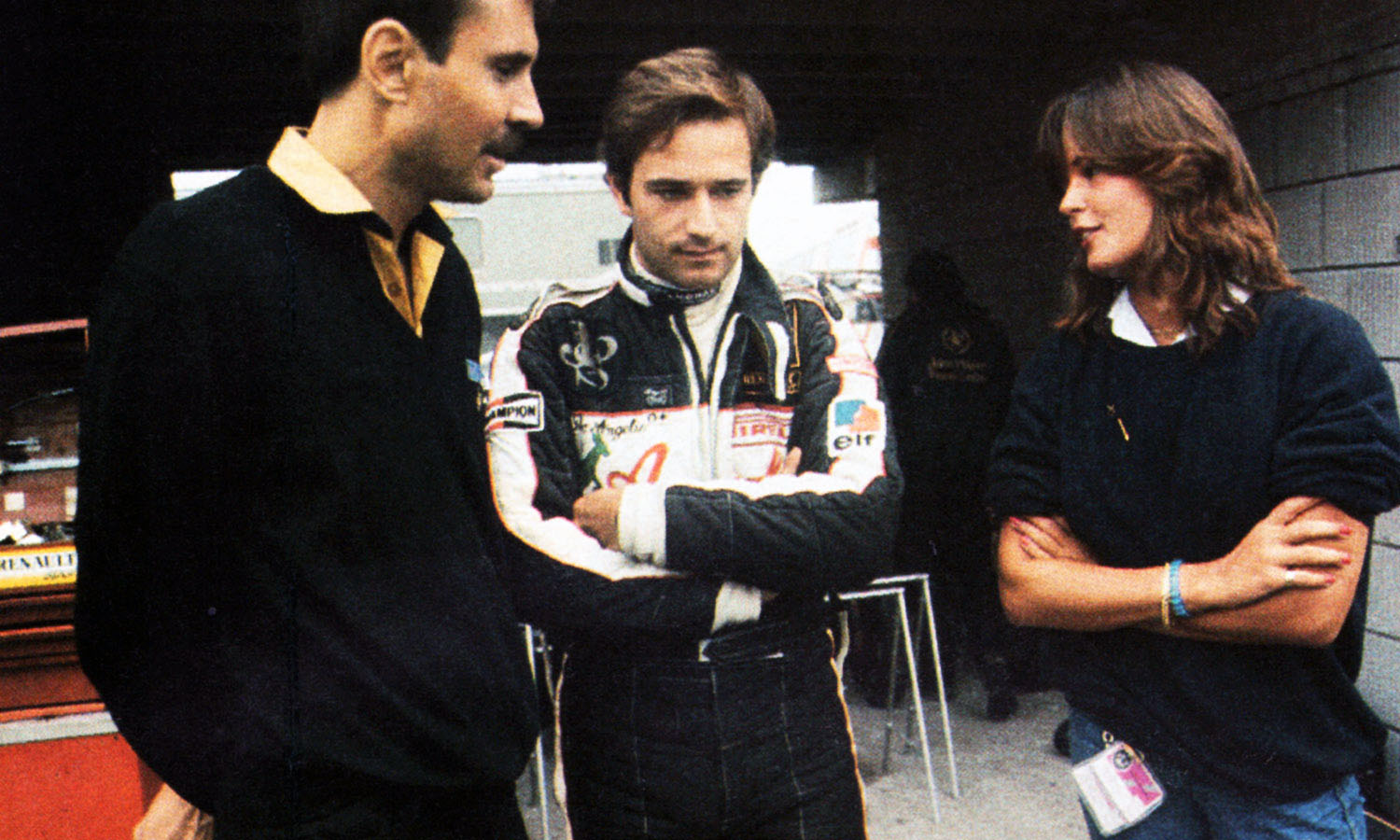

His year at Lotus is too recent to require detailed recounting here. Suffice to say that Elio has fitted into the team well, working sympathetically with the mechanics and engineers. His relationship with Colin Chapman is formal, slightly distant, yet profitable. How else could it be when the employer is fifty and employee twenty-one? Elio is young enough to be Colin’s son. But there’s no doubt that de Angelis has the sort of confidence in Chapman that breeds success. He’s impressed by the Lotus record and believe in the Lotus legend, although he’s not blinkered in his outlook. He believes that, if he stays with Lotus, the right car will be his before long.

In 1980, without doubt his best race was at Interlagos in the Brazilian GP. Running on winner Arnoux’s tail, he demonstrated commendable restraint and eased off to finish second when he realised his tyres wouldn’t otherwise go the distance. His most frustrating run was at Watkins Glen where, his Lotus 81 fitted with revised suspension pick-ups which immeasurably improved its handling, he qualified third on the grid. “But by lap four I realised that I couldn’t quite stay with the leader. That was agonizing.” He still finished a worthy fourth.

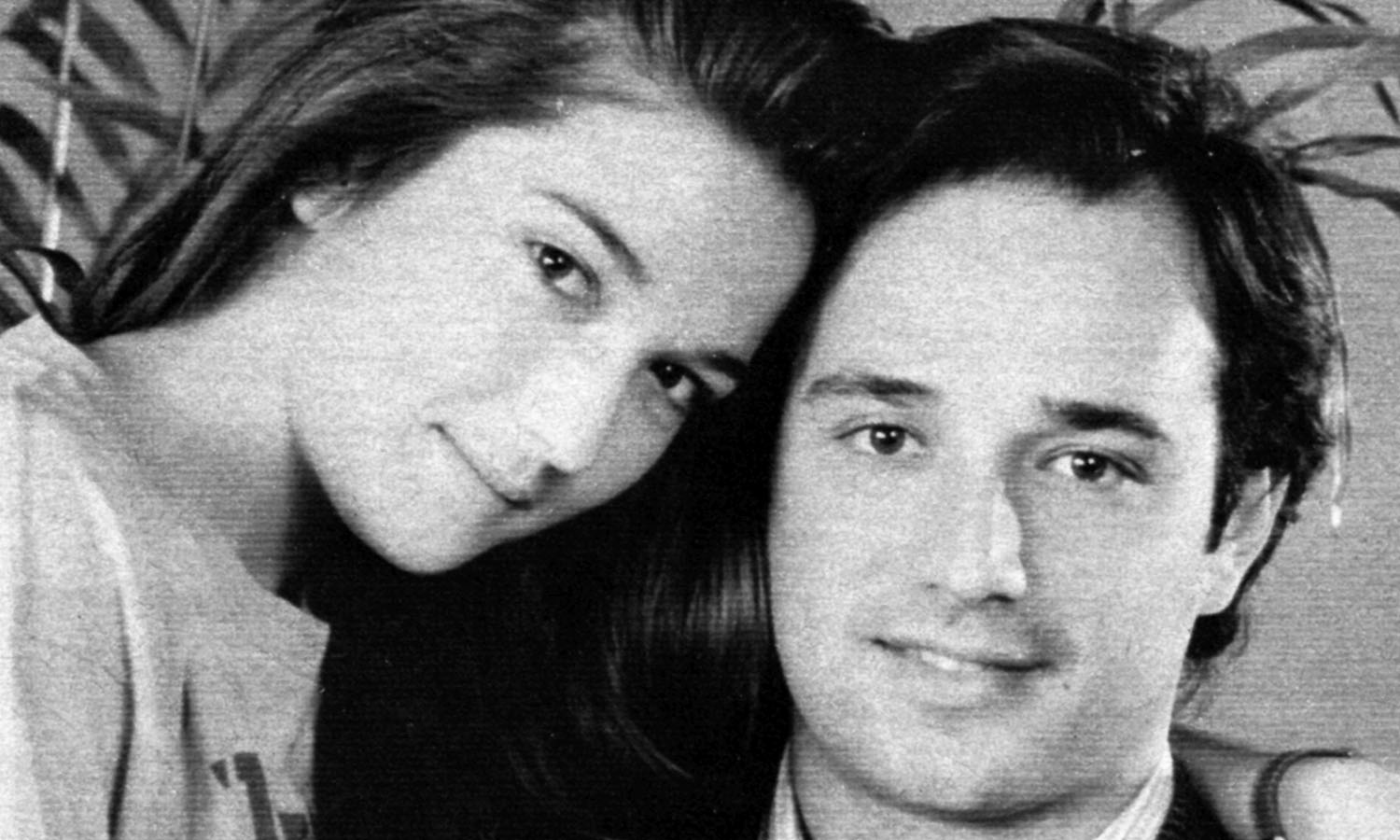

Elio leads a quiet, reserved private life in Monte Carlo. He moved there recently from Rome and his parents will be leaving Italy in the New Year to live a little further along the Cote D’Azur.

He doesn’t like talking about the social and political problems which have befallen Italy over the past decade, but he obviously worries about them passionately. The fact that Elio has used an armored limousine and was escorted by an armed bodyguard on his recent visits to Rome underlines the stark reality of kidnap risk for the more wealthy of that country.

They were frantic with concern.

Aside from a burning ambition to triumph in the World Championship, Elio would also “like to have a crack at Indy I think that I’m crazy enough to do it. But as far as Formula One is concerned, I don’t have any great romantic aspirations about which team I’d like to drive for. In Italy you’re supposed to want to win the Championship in a Ferrari. But that doesn’t matter to me. I don’t care which team I’m driving for. I just want to do the best job I can for the best team available at the time.”

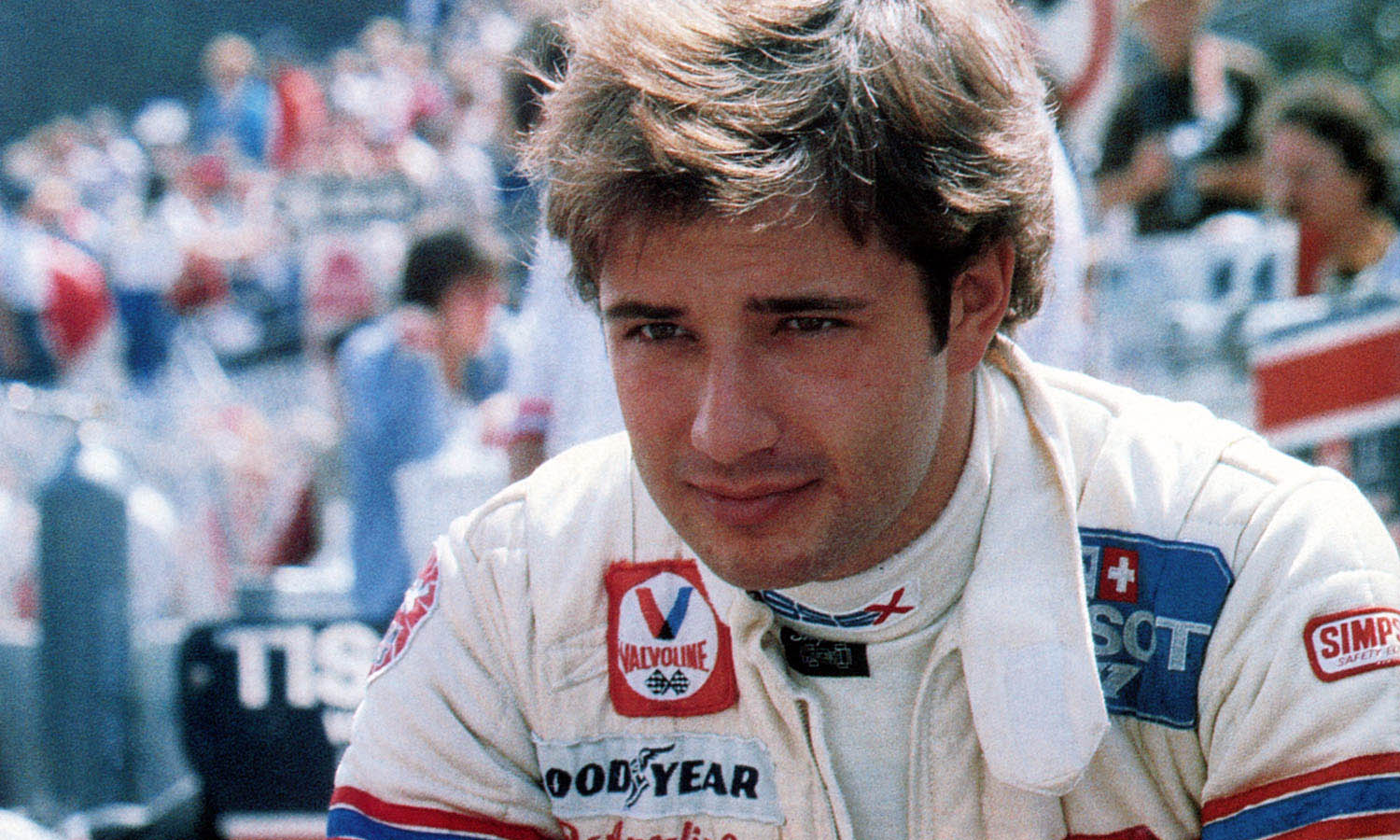

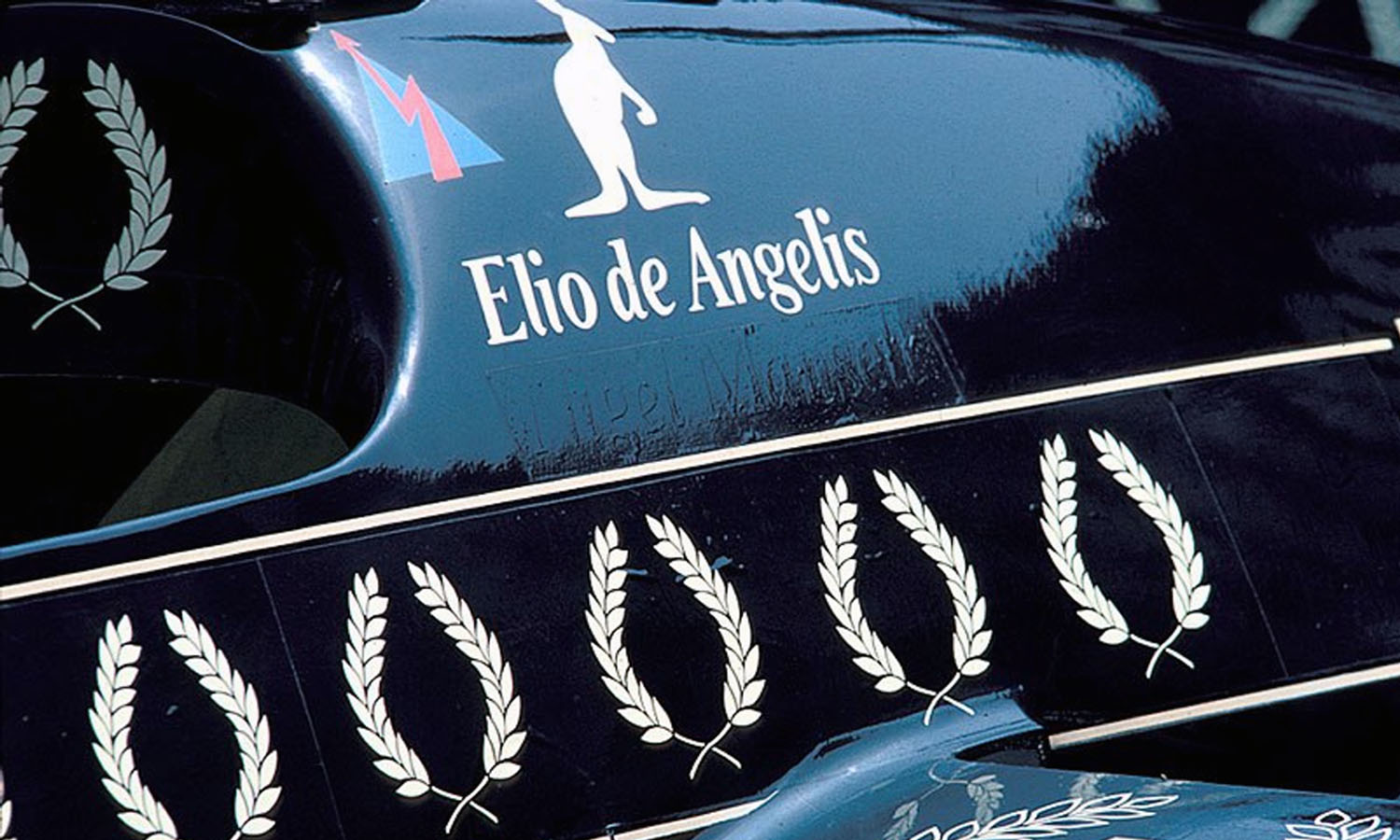

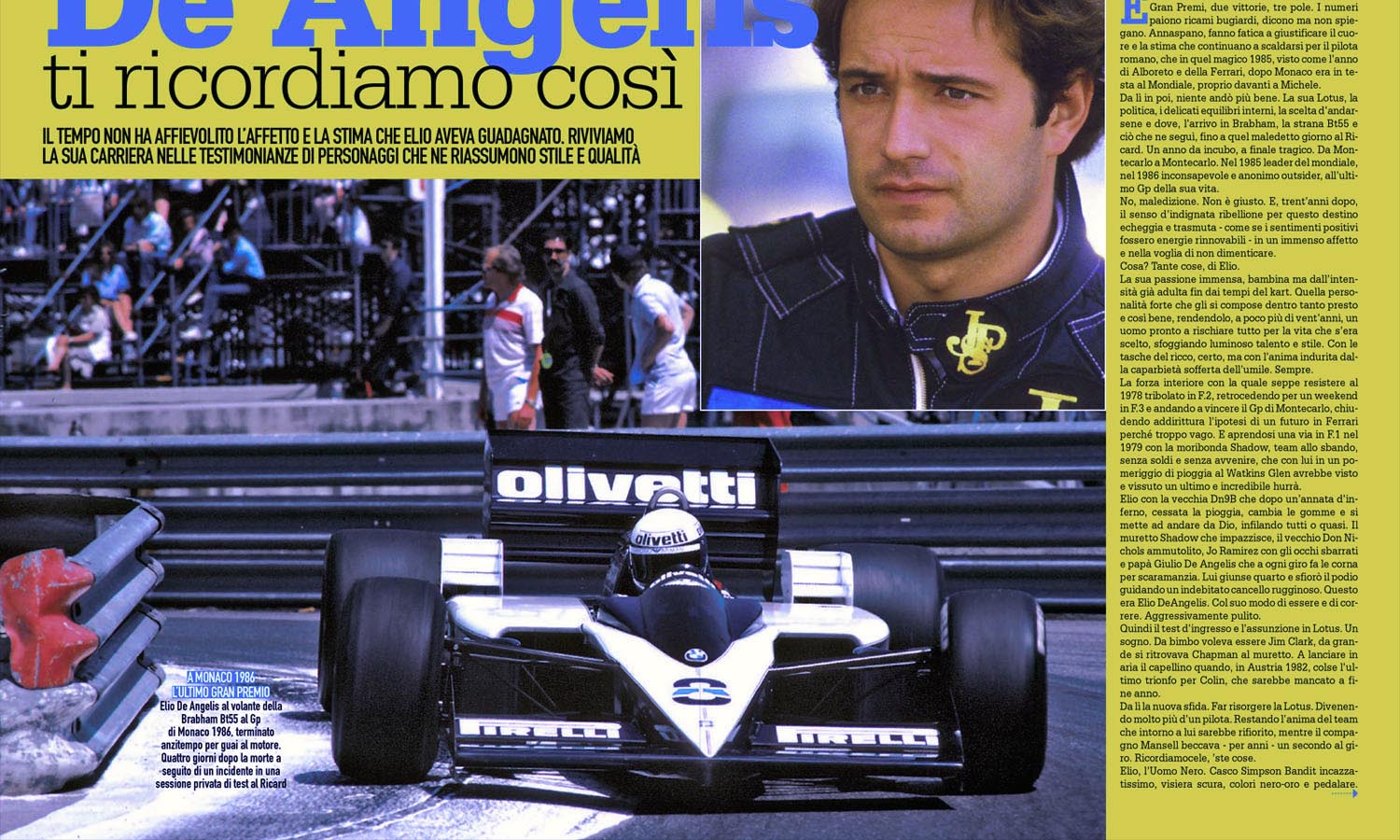

For 1981, Elio de Angelis becomes the youngest Team Lotus number one ever, and also the first Italian to drive for the factory. He has an exciting new Grand Prix car to contest the World Championship. At the age of 21 years, he is entering his third season as a regular Formula One competitor.

Now, at last, it’s all down to him.

© 1981 Motoring News • By Alan Henry • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended