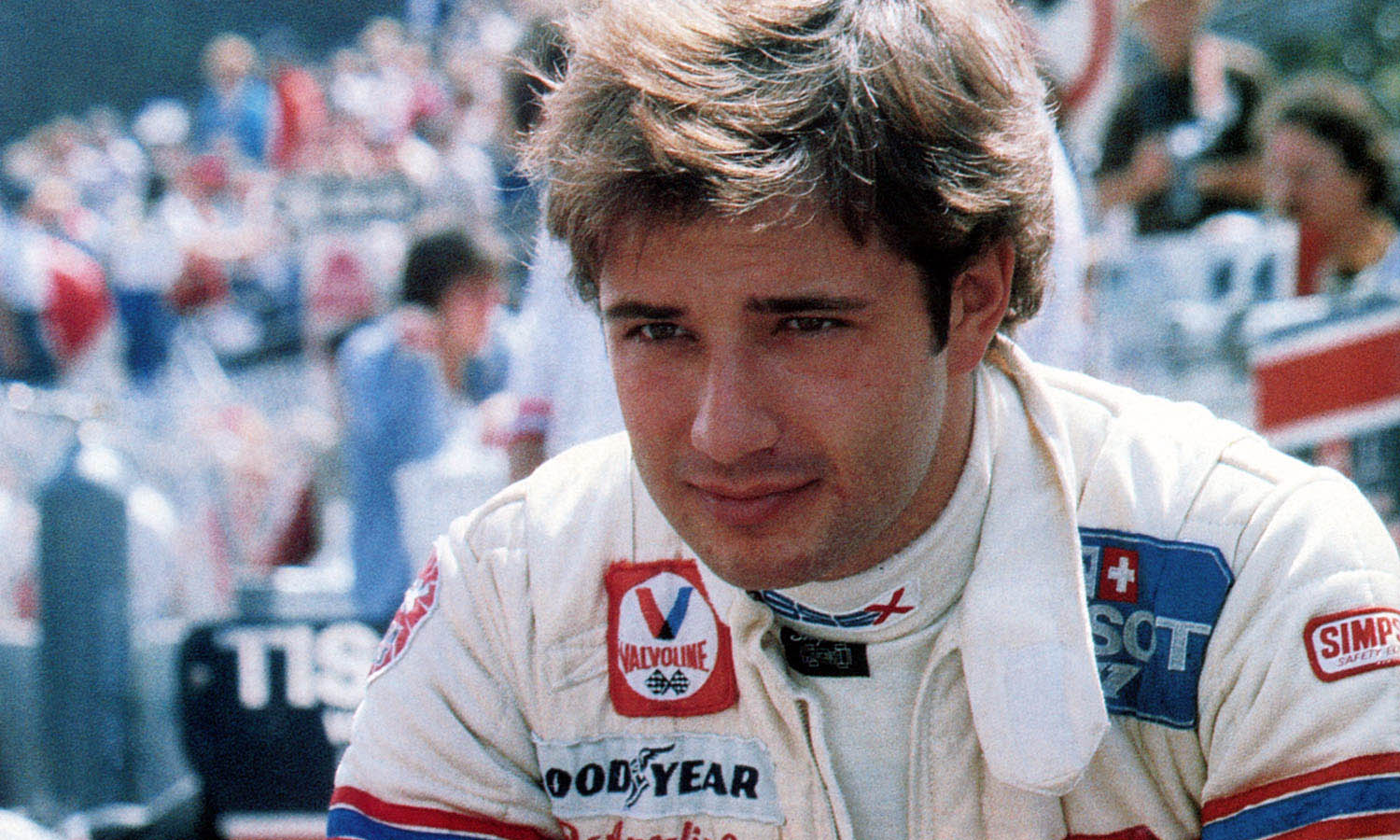

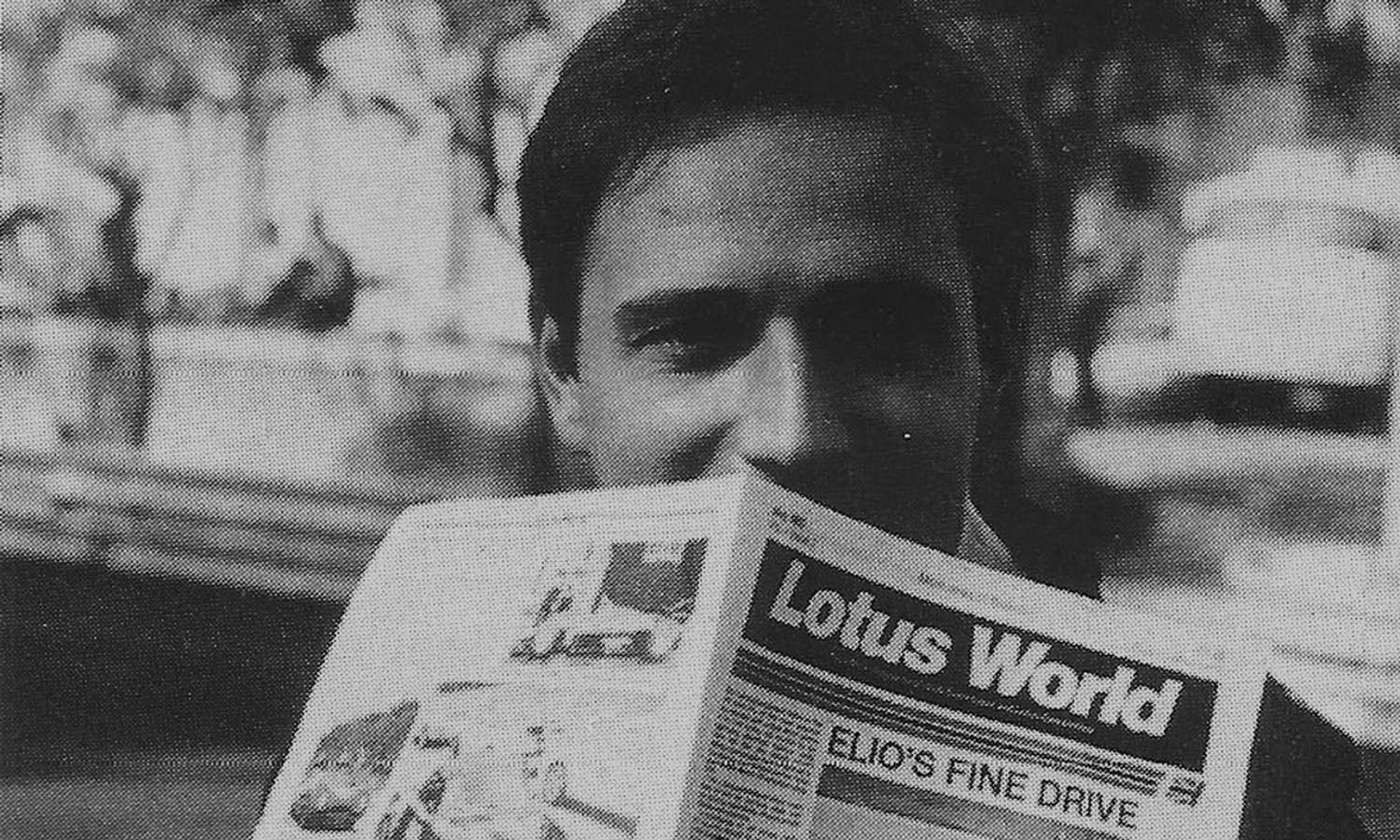

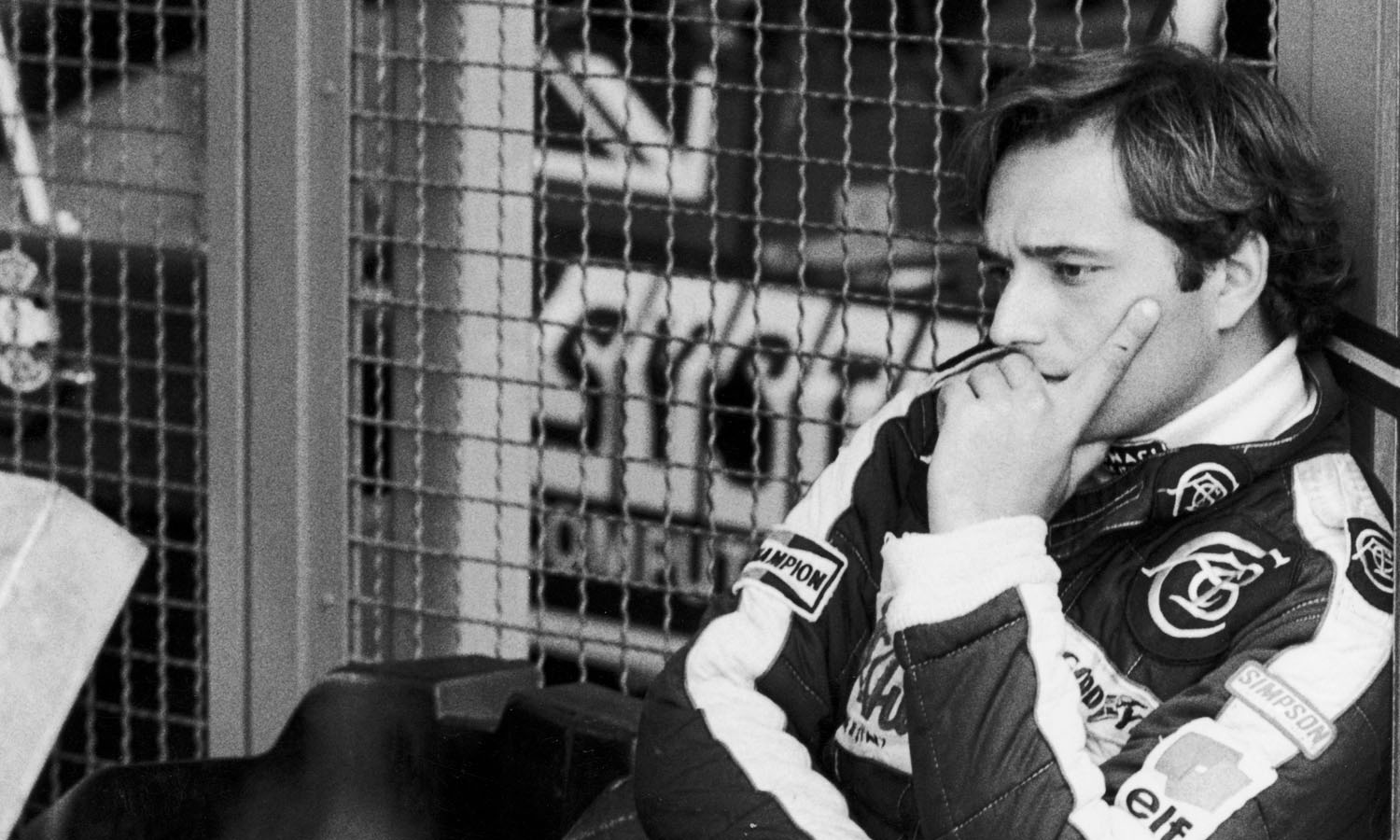

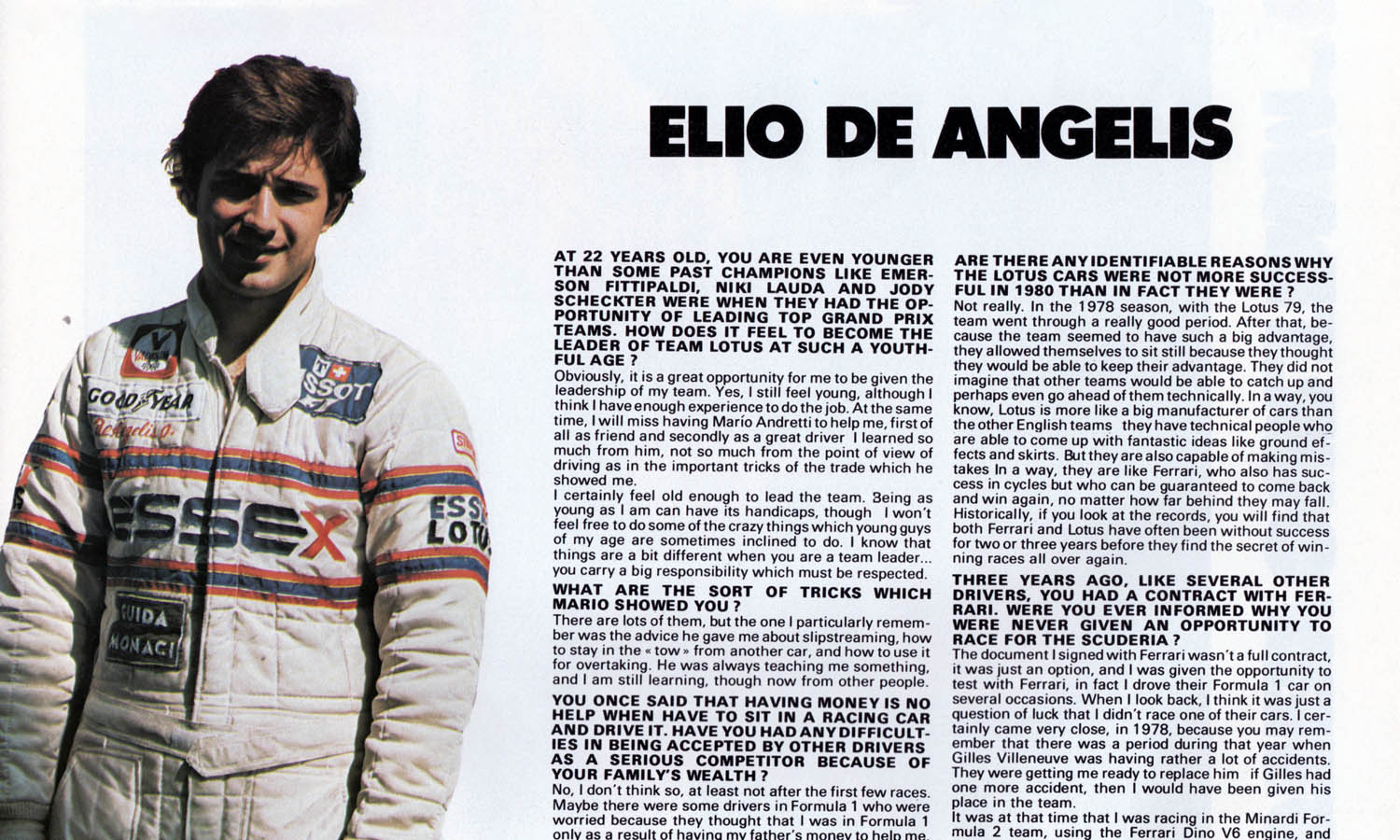

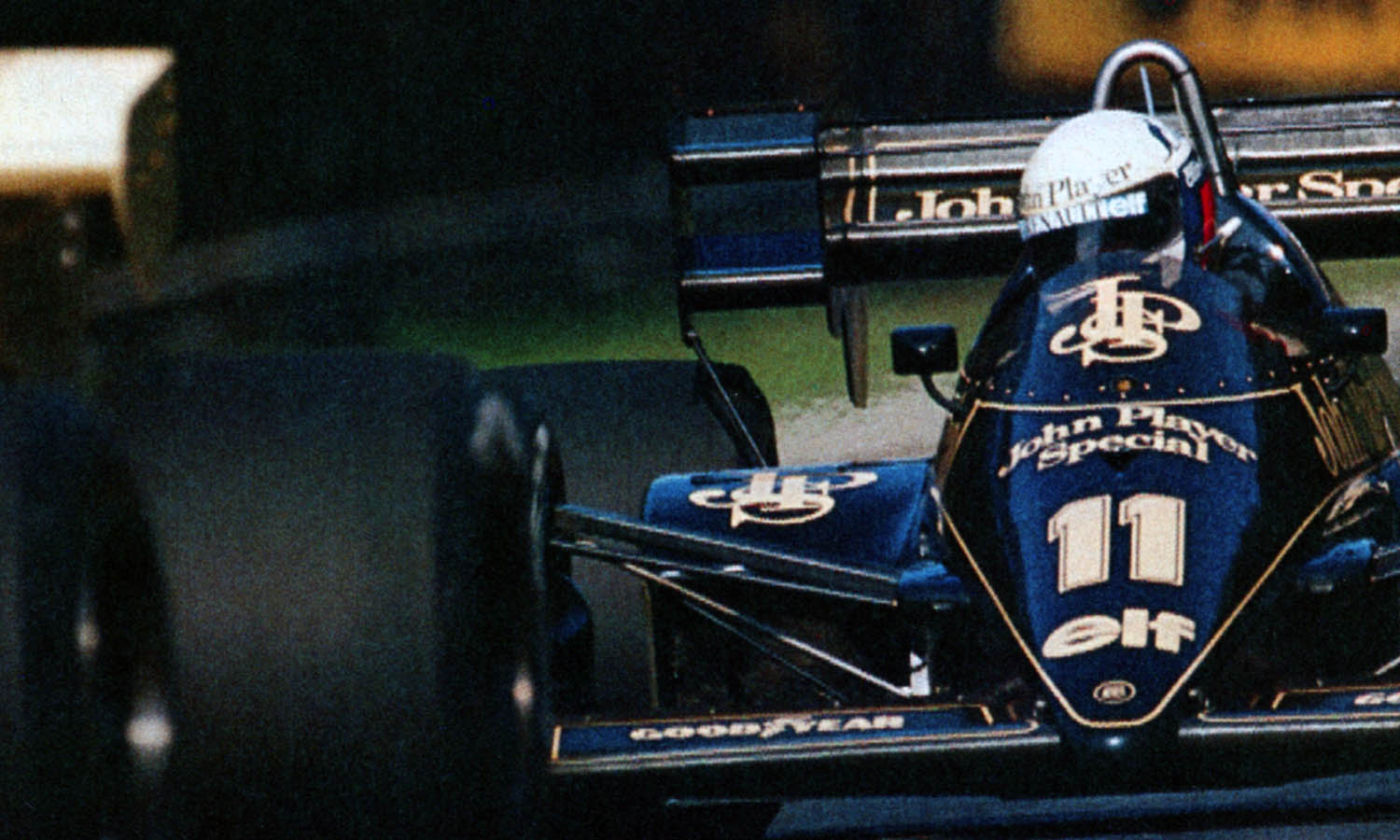

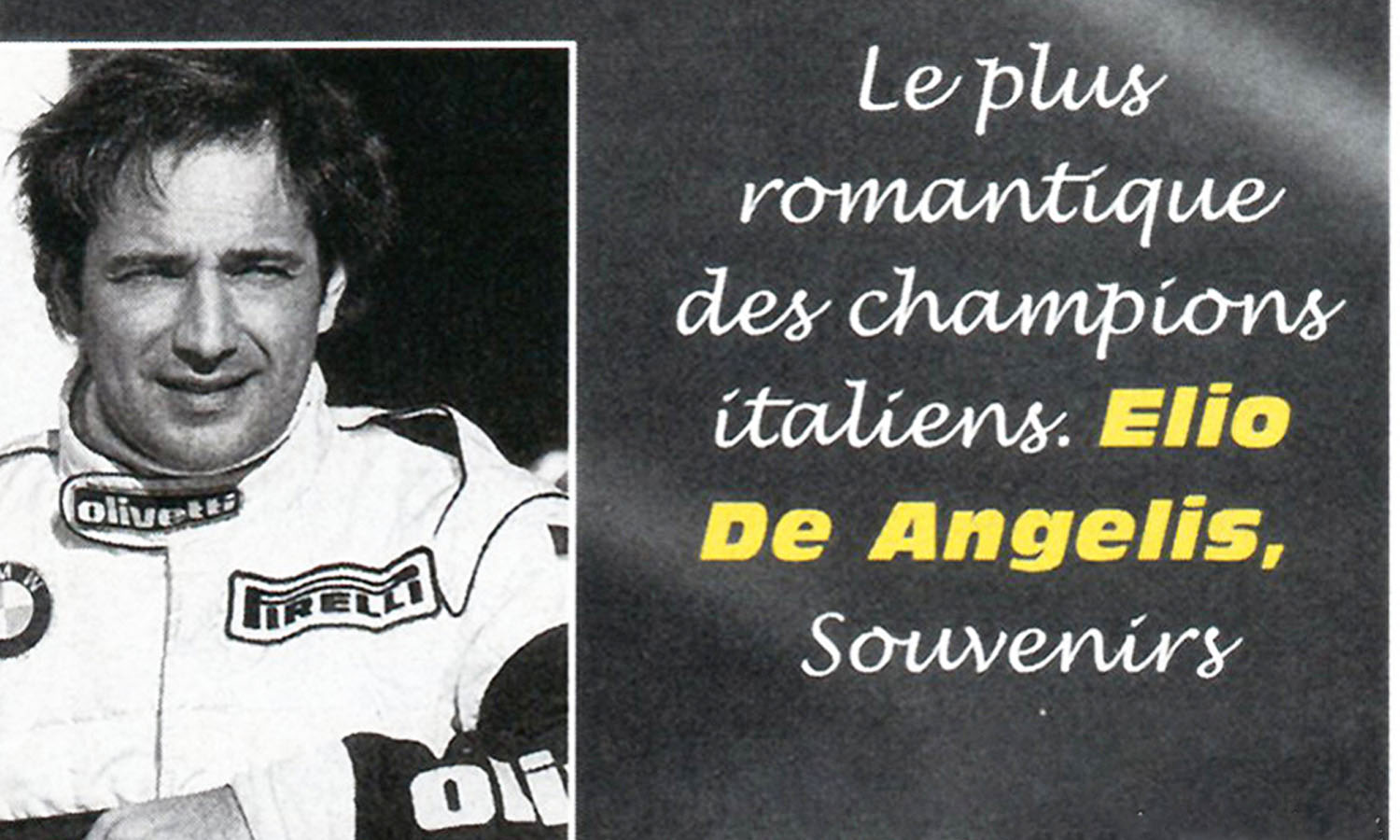

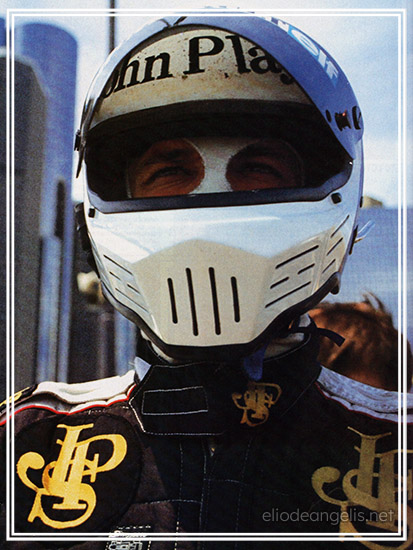

The young man is still only twenty-six, but Dallas was his 81st grand prix, more than Rosberg or Prost. He started his F1 life as the son of a rich father, acquired a reputation as a dilettante; stuck to his guns and this season lies third in the championship in a highly competitive Lotus. Competitive and reliable, for Elio has finished every race but one in the points. The man himself remains private, patrician, roman in short.

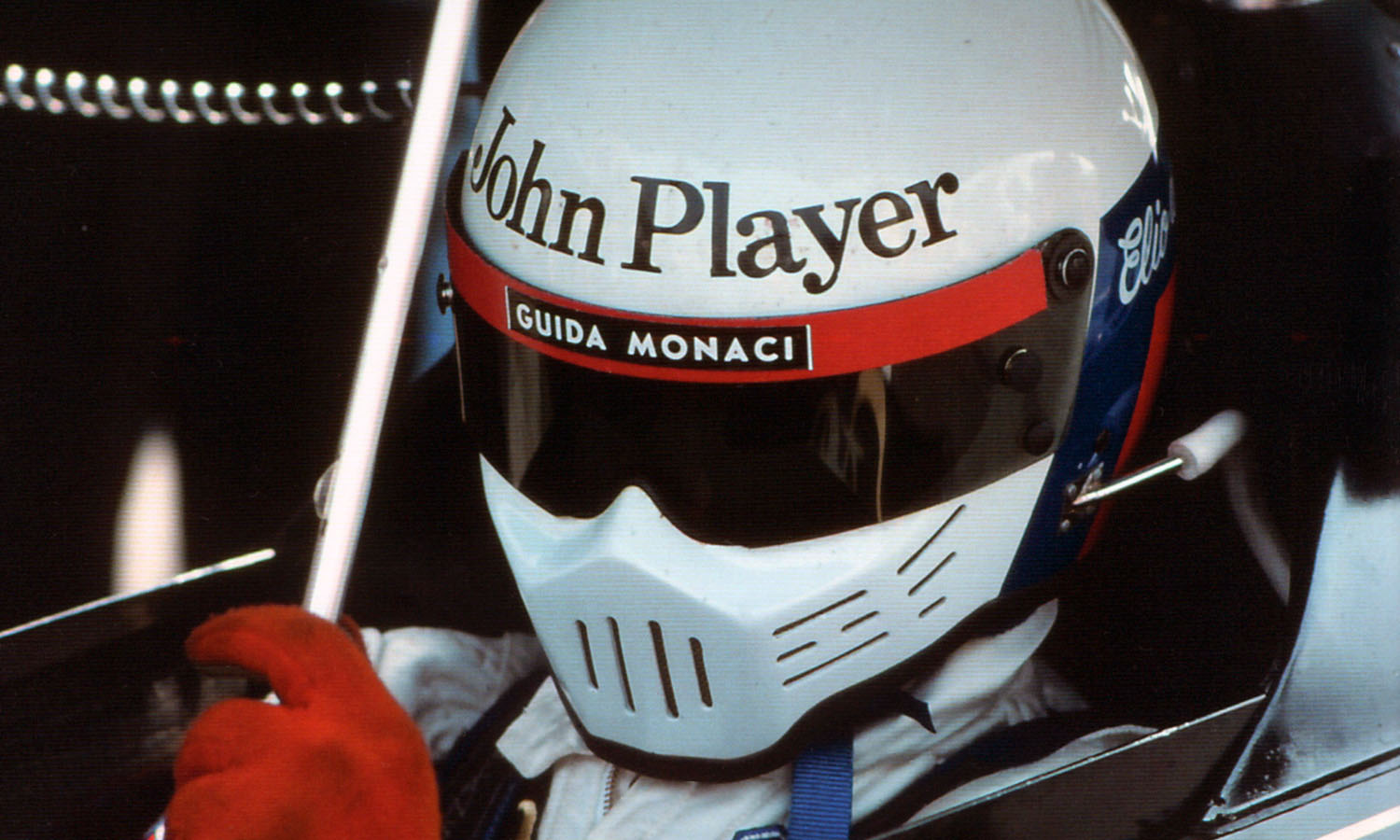

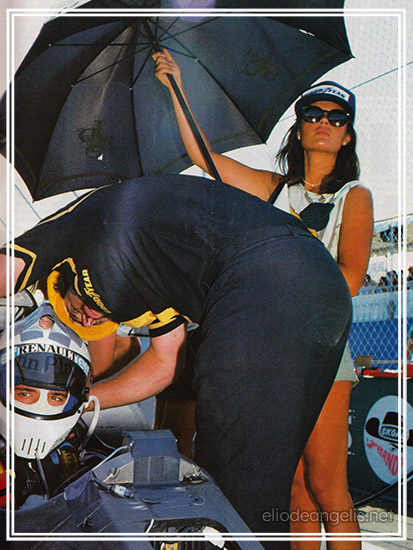

We are in the mall of Loew’s Anatole the day before the 1984 Dallas Grand Prix. Elio has to get to bed early to rise the morrow at 5.30 to get to warm-up. He needs his eight hours. The next day he will drive coolly and intelligently – against the grain of his car which is misfiring and his rubber which is gone – to finish third. On the eve of a race, it’s not about that a driver wishes to talk. These are among his few private moments: sometimes, not always, drivers like to talk for it articulates their feelings.

We begin on America, because that is where we are, in Dallas heartland; and Elio’s not happy here. “Americans are so different from Europeans,” he begins.

“I used to like it more here,” he continues; “but I was myself different in those days. But now I see that there is a culture gap between Europe and America that you really can’t ever bridge.” Of course, he agrees that his profession is a barrier. It’s hardly bridge time at the track. “I know it’s a superficial judgement, but I couldn’t really live here. But one thing I do like is that in America you can live your own life, you can create it yourself.” Drivers, we agree, don’t lead real lives. “I go to a place to drive,” says Elio. “That distorts life.”

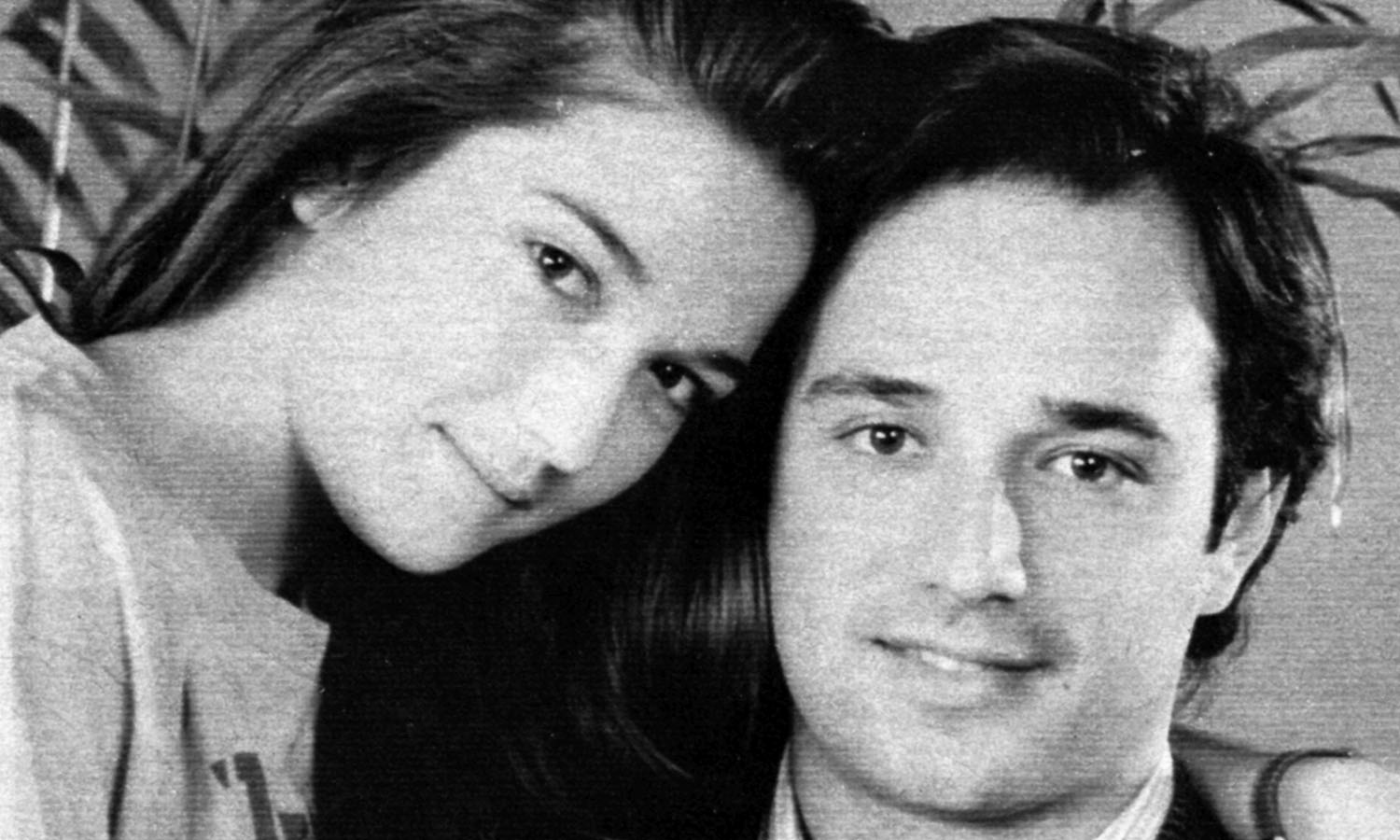

In contrast, he like Germans: “They have class. They are Europeans, but they are American Europeans. They stick to their word. And then my girlfriend (the lovely Ute) is German!” Which leads, obviously to an excursion about love and marriage, which need not concern us here. It is a subject on which Elio is at least in three minds. He is a perfectionist, in that as in all things: “If I do something, I like to do it well. And yet I do so many things well and do them only by halves”.

Because one of the things Elio has always said is that when he finishes racing, he wants to write music: not every driver’s ambition. During the Kyalami strike, Bruno Giacomelli was the court clown, but Elio was their musician. “I studied hard when I was little,” he says. “I did classical piano until I was eight. Then I couldn’t stand being in short pants and going off to practice in old buildings, so I gave it up. Then I took up the piano again when I was twelve, but I’ve never perfected myself in the instrument. My second start was with the blues, though I’m coming back to classical music, too. But you see, I gave it up because my teacher heard me one day; I was playing Brahms as blues, and she threw a fit! How could I destroy such music!”

As he says, he doesn’t like playing the music of others. Best of all, he likes to do his own thing, a form of improvisation. Could he do it professionally? He’s had offers: “But they wanted me for my name, not for my music.” He has cassettes ready, but “I’m not yet ready myself. I’d get caught up in it. I am in racing and the two just don’t mix.” Also, he can’t write music. From Ray Charles and Stevie Wonder on is his bag. By ear. If his ears last out the noise of the cars. Other things, too, he would have liked to have done. “So many others,” he sighs. “Driving is a limited world, but the truth is that driving is the only thing I’ve always fought to do. From the moment I could think and reason, it’s the only thing I ever wanted to do badly enough. So, I continue to struggle, even If I like it less now. For good or ill, I am ‘established’. When I started out, it was for purely sporting reasons, and it seemed to me a pure sport.”

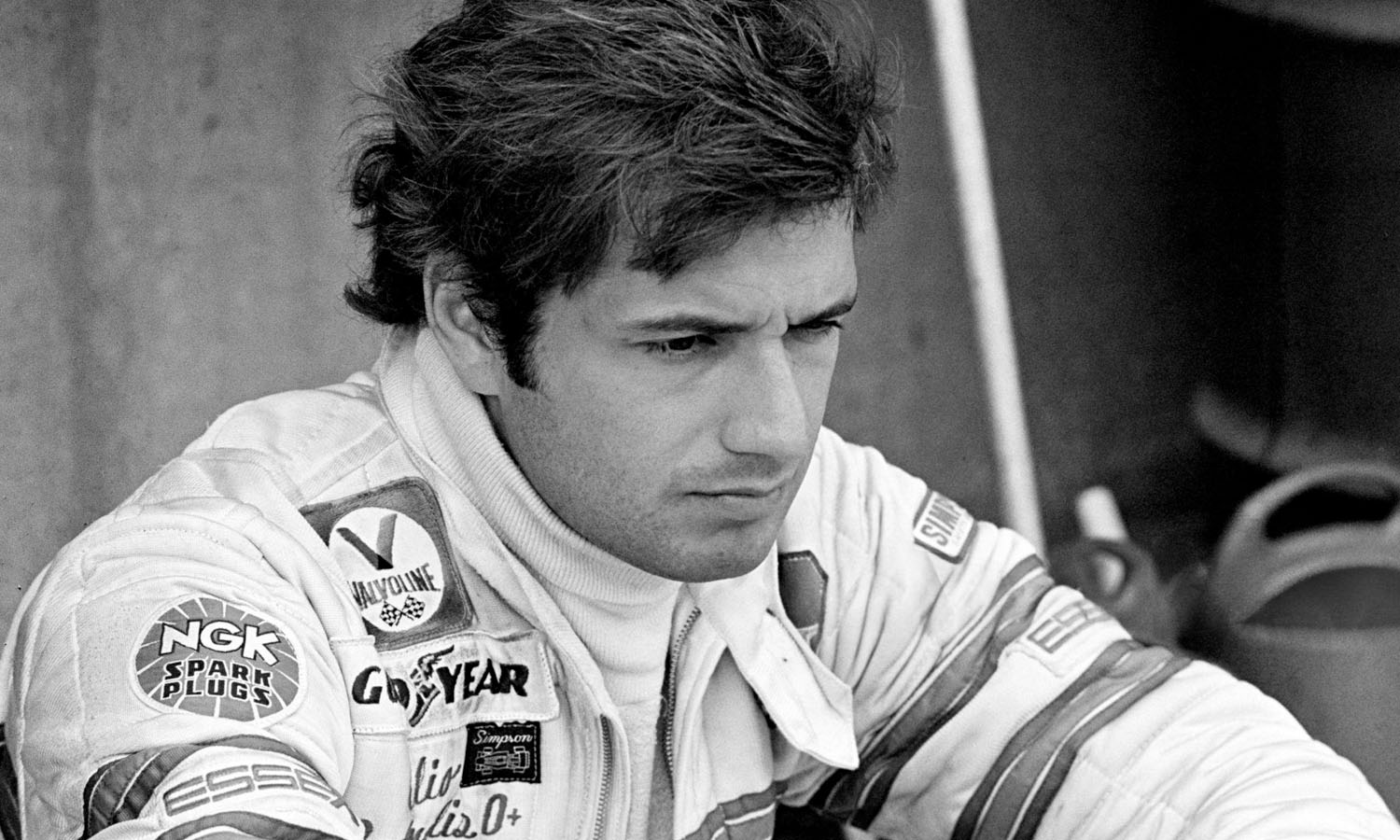

At which point arises the obligatory question. Why, if he likes it less, does he drive? “I was six or seven and I had a little red pedal car. I used to play with it in the garden. The ground sloped away: that wasn’t enough. I’d make my brother, or my cousins push me so I could go faster. By ten, I was too big for the pedal car and I got a bike. I put a steering-wheel on the bike and a helmet on my head. By then I was already watching Jim Clark, Rindt. As I grew up, I became another Ferrari Freak. Always wondering why Ferraris weren’t winning.”

Now Italians do sometimes follow Italian drivers, and not just Ferrari drivers. But if Elio wins, it is still not the same thing as Ferrari winning. Not in Italy. And why not? “Because that’s the way Italy is,” he answers. “Ferrari is a myth, like Garibaldi. For good or ill, in an Italy that’s undone, that’s all ups and downs, Ferrari remains part of the mythology, like the Italian football team.” The nation needs triumphs. But Elio doesn’t feel out of water in England or racing for a British team. “At the beginning, yes. But Italy never made me feel particularly Italian,” he explains. “I think I am very Italian, but Italy never adopted me. Not in the right way. I had to emigrate. It wasn’t my intention to race in England. In Italy they told me I was finished when I was nineteen. The English helped me to grow up; they have shown me some of the harder aspects of life. I owe them a lot, especially when you think that the first time I raced in England, for team ICI at Brands, I spoke not a word of the language. All I could do was point: tyres no good.”

Of course, he’d been to England before, on trips with his family. “For me, it was just the Beatles. The Beatles and Carnaby Street, records and clothes I could bring back to Rome.” He remembers the brightly coloured shirts, but never got to see the Beatles live.

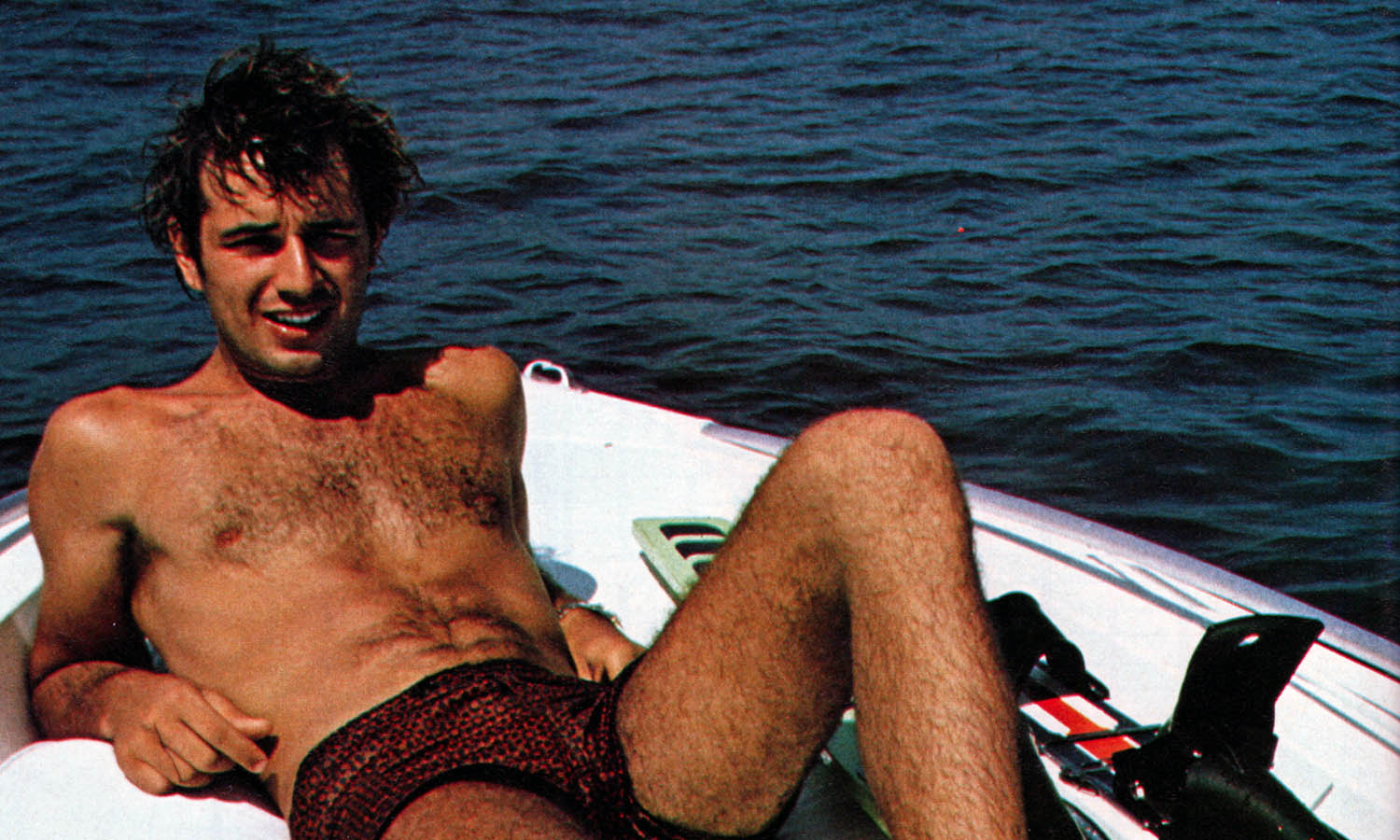

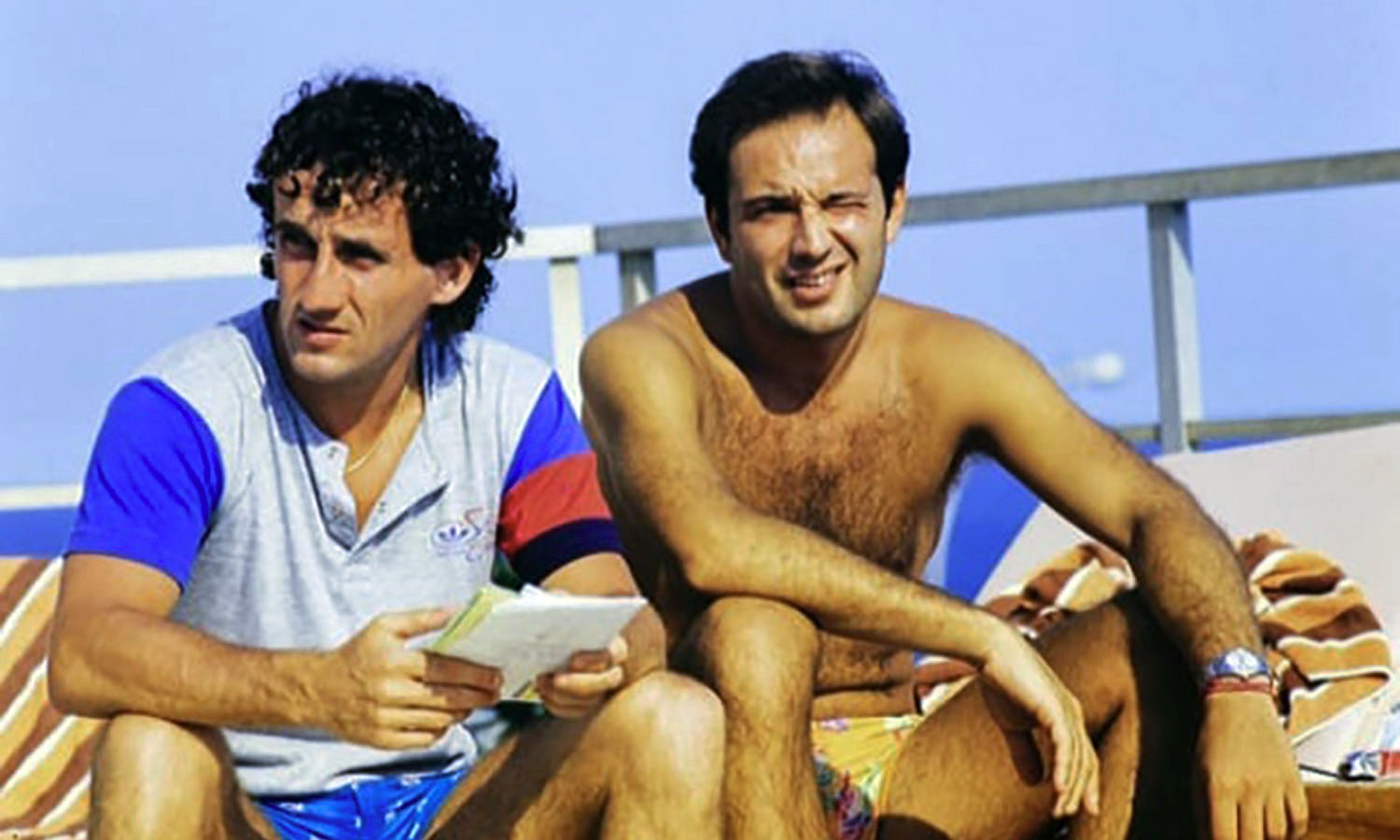

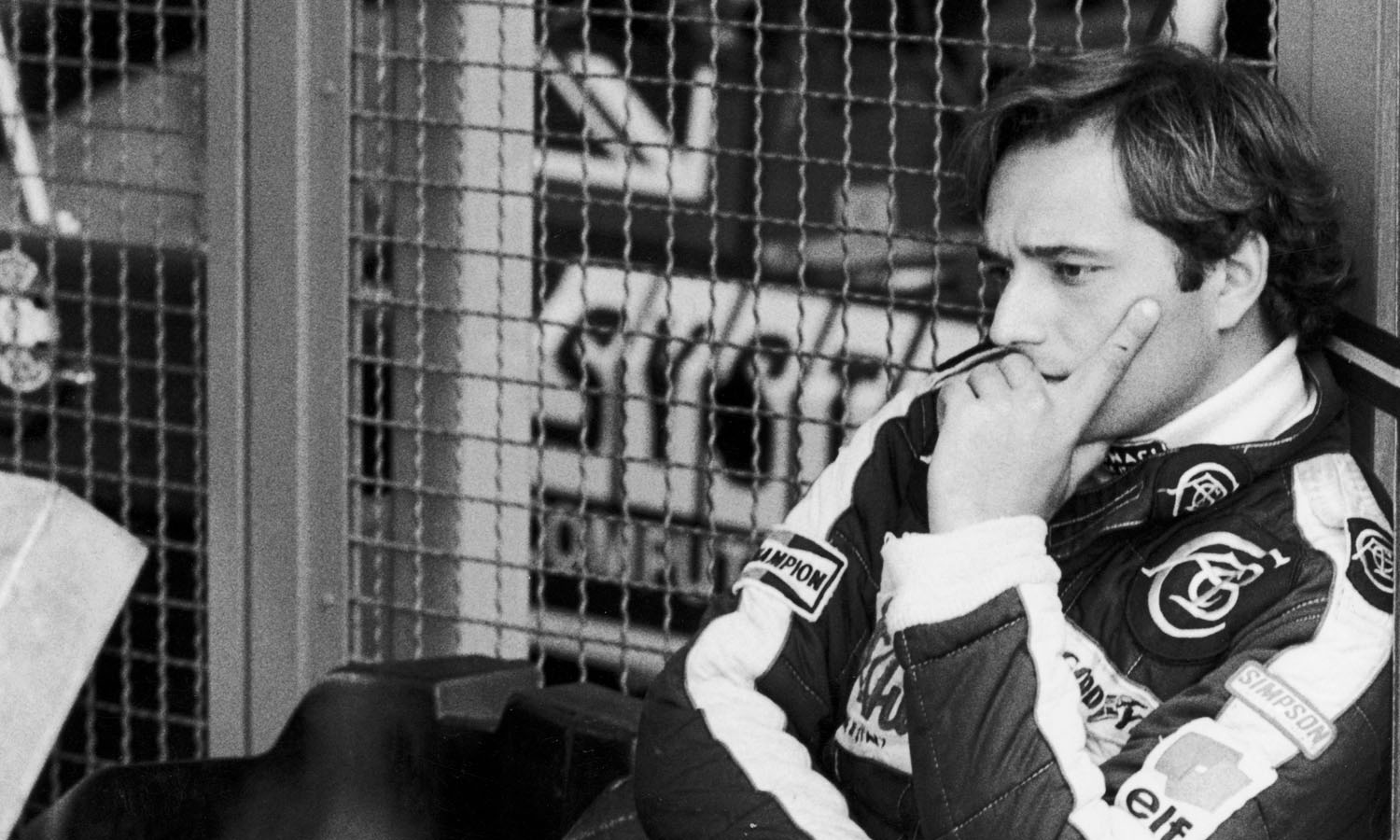

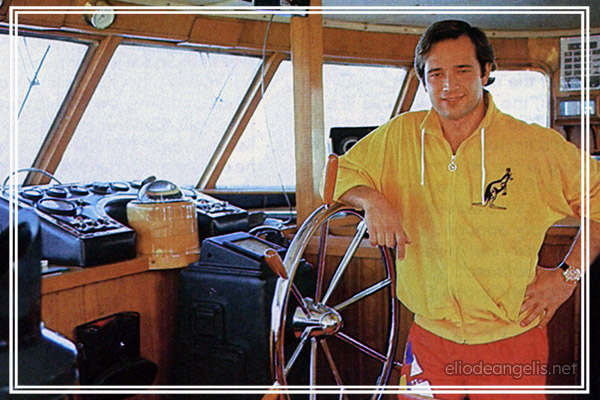

Otherwise, his early horizons and even some of his current ones are limited to his two great loves: the sea and the sun. “The sea gives me a sense of freedom,” he explains. “I like looking out there. If you look up at the stars, you are lost, it’s frightening; the stars lack dimension. But the sea gives you space with dimension.” Of course, his family, as he points out (no false modesty here), owns shipyards, boats… I go back to Motor Racing. So, he’s ‘established’ is he? “No one is ever established,” he answers. “I could get a letter tomorrow morning.” But as he told me in Detroit, he does feel more solid in his profession. “I think it’s a question of becoming conscious of your own value. You grow up within. As a driver, I feel I’m still growing, because I’m still young, and yet I have a lot of experience behind me. What is difficult is to integrate that experience into your life as a whole. For instance, I remember little of my first two years of F1, but last year I remember perfectly. Not because it’s more recent, but because I now think differently.”

“At your age,” he adds, referring to to my emerging grey hairs “you know who you are as well as what you’ve been. Mine is still in evolution. Things change, circumstances are still changing.”

In the shape of his life, as Elio would admit, his father has played a large, even a determining role. “Our relations have always been very close. Probably because I am very like him in some ways and very different in others, so we have our encounters and our differences about life. But we love each other greatly. We talk to each other all the time: both about his life and about mine. I worked a bit in the business, and I lend it an ear; the door is not shut and now my father, my brother and I are for the first time in business together, putting together property in Sardinia.”

The Daddy’s Boy in Elio is shifting fast. It was a hard tag for Elio to get off his back. “I never felt I was Daddy’s boy,” he says “my father never spoiled me. I could have become one if I’d wanted to; my father could have let it happen. But I was always thinking — and this is where sometimes my father and I argue — about who I am, what sort of person I am, me as myself, not as a product of my family or my background. You have to build your own life and if you don’t know how, you’re not living a life; you are bound to someone or to something. When you’re young, there are no in-betweens. There’s black and white but no grey. Sport, too, is black and white. It was a place I could express myself”.

The grey, then, came later. When Elio saw the sport was no longer pure. What had he meant by that? “It’s a strange sport now. It’s a way of being famous. It’s a way to success. Success is a very important fact in a man’s life. Otherwise, without success, everything I’ve done until now would be valueless. I started in F1 because it was a form of intoxication. I liked to dominate a form of intoxication. I liked to dominate a car. Now I know how to do that, there is a less left, though there are always things left to learn. So, it’s not quite true that I know everything there is to know. But what is stronger in me now is the will to ‘arrive’. Not to be 101% fit, because you could still have a bad car; but in this sport — which I still think of as a sport — to have success and to know how hard it’s been to come by it”.

But, as we know, F1 is also commerce and politics. The former, being rich, Elio can perhaps do without. The latter? “I still like the sport; I despise politics in the sport as I despise it in life. I’m not a diplomatic man. As my father constantly points out: ‘Why do you do things the hard way?’ he asks. The answer is that it gives you more satisfaction.”

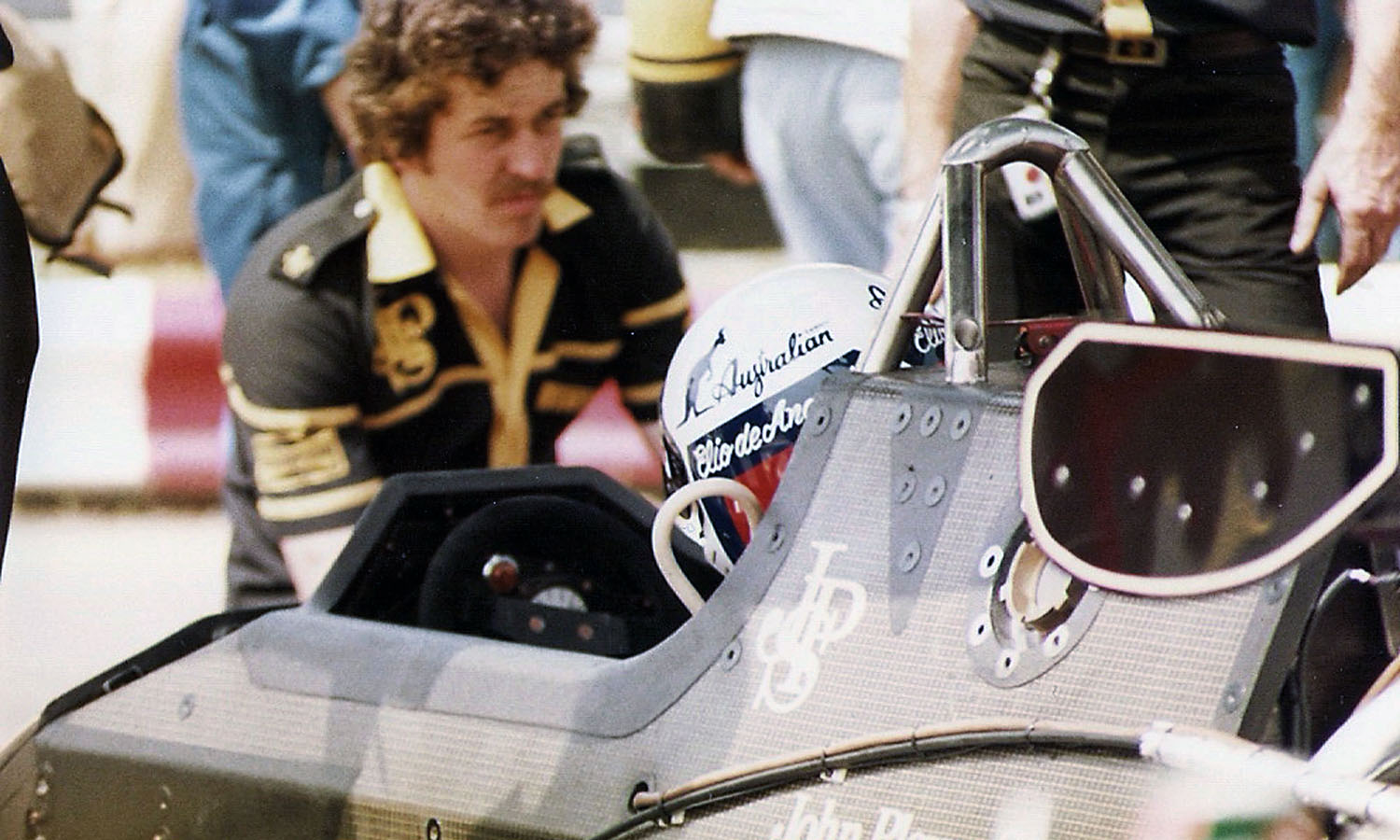

I am surprised by this lack of diplomacy. Elio is all grace and manners. He answers, disparagingly, that “that’s all part of my upbringing. That puts a brake on my public expression of discontent”. Not always. He had one set-to with Colin Chapman that he remembers well. It took place in Las Vegas. “Colin was a person with a sort of halo about him, it was hard to get close to him. I felt that I was part of his car, that he didn’t really see me. We had no human relations as such. But in Vegas – there was a problem of who was the number one driver — I gave him a real blast and he gave me one right back”. It was part of a long-standing quarrel between Elio and Nigel Mansell, who at the time, was the apple of Colin’s eye. And was getting the better deal. “I was right,” Elio continues. “I couldn’t go on in that situation. Colin said it was because I sometimes didn’t appear to be putting in all the effort I might, I wasn’t professional, I was in Ibiza when I should have been testing. It was his way of punishing me.”

“From that I learned. I learned that I had to take my job more seriously. But when you’re young, you think you can do it on sheer talent. You make the car go faster than it will go. When you succeed, all is well; when you make a mistake or when you get hurt, then you think, maybe I’m not all that omnipotent. You learn to be a bit smarter. It was a bad scene, but it was the first real human contact we had, and that was better than bottling everything up.”

“At the time I thought I might even go back to Italy. To go back as someone: that meant a lot to me. But I didn’t go back. Colin insisted I stay. He even sent a cable to the President of the Republic! Colin was not your normal Englishman. He was more of a Latin: both in moments of panic and his moments of genius. He was in tears when I won in Austria, and I was in tears when I heard he died. He was a bit of a father to me. A father in racing. he gave me confidence. He’d say “I’ll build you a car to win with…”

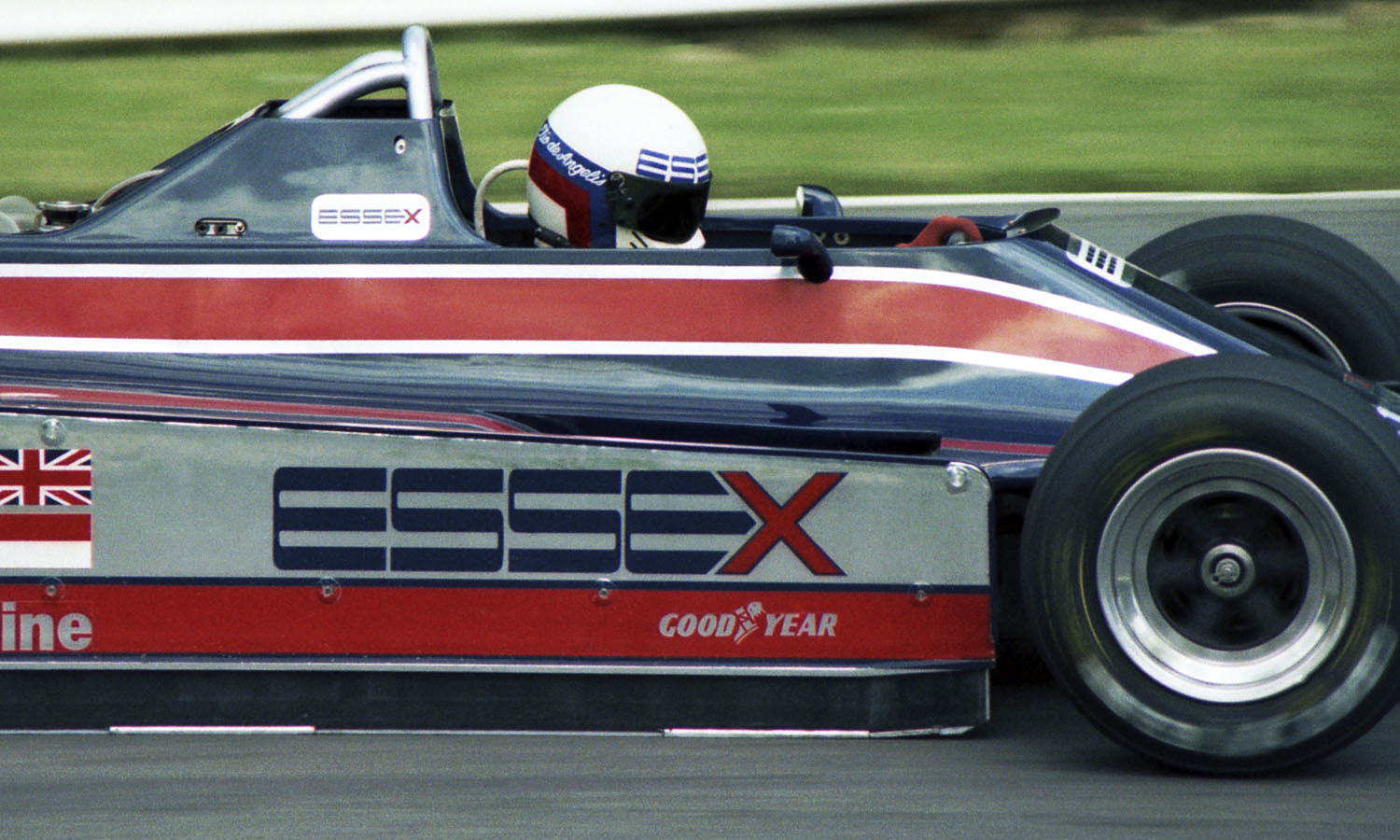

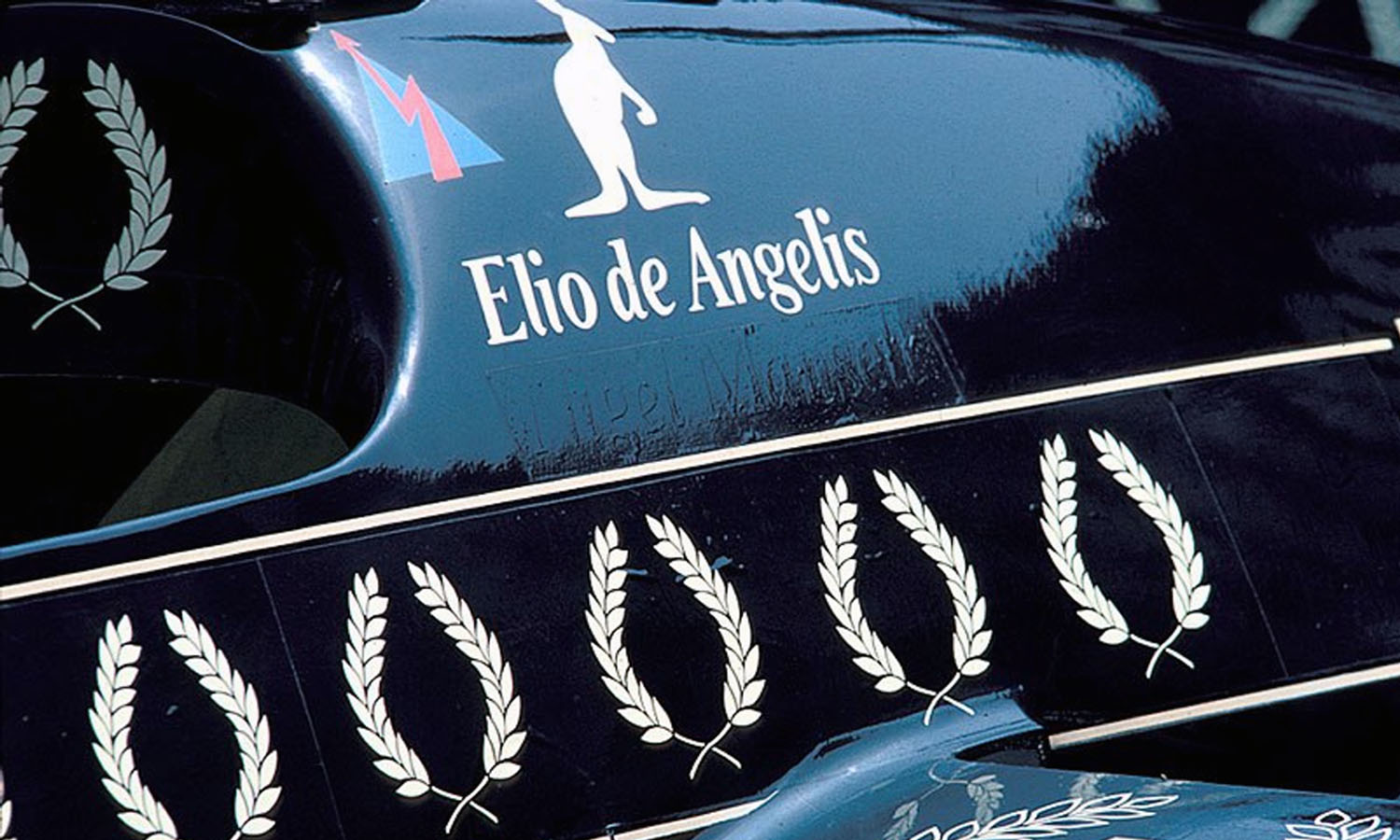

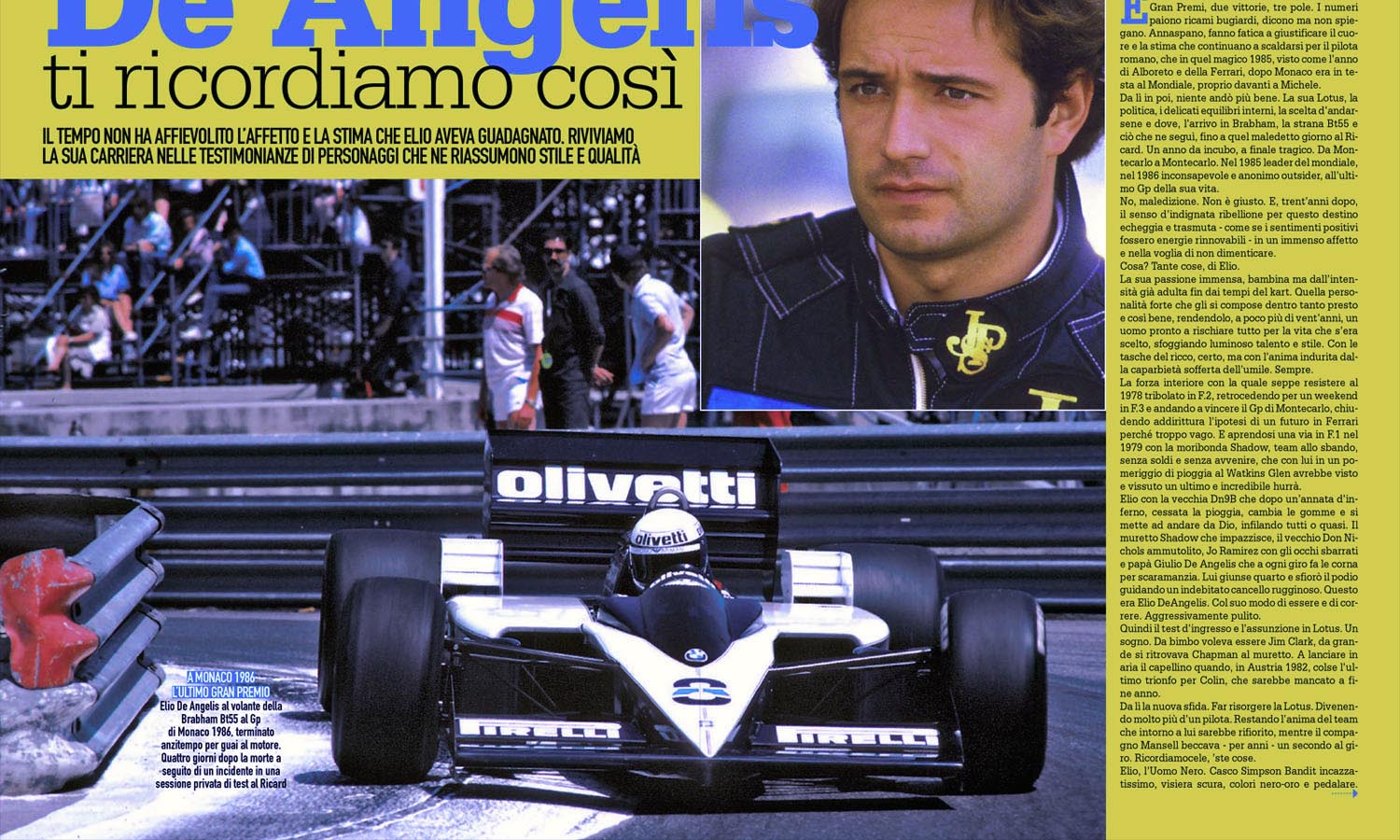

Things are very different at Lotus now. Elio no longer races for Colin Chapman; he races for himself. “I’ve built this year on the horrors of last year,” he says, “the year of the great NO. I knew my stock was slipping; I was making mistakes I hadn’t made for years.

I had to prove I was a man and I think I’ve succeeded in doing so: even if last year I finished 17th in the Championship. It was the most critical year for me. I was 26 and already I had no future. Now I race for myself.”

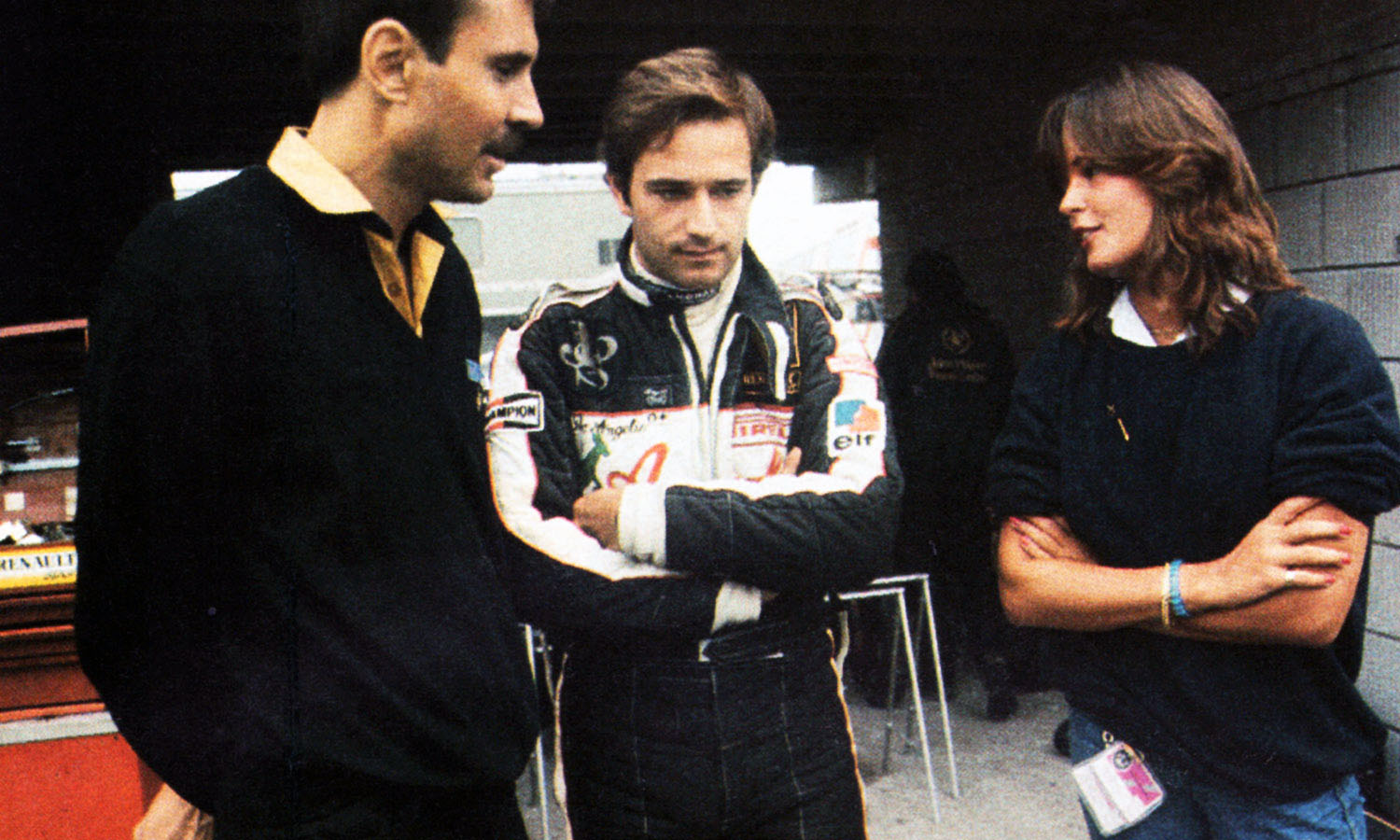

Gérard Ducarouge has been the man who has made the difference. “We always had a certain feeling for each other; we always thought we might someday work together and as soon as he was free, he came to Lotus. I was one of the reasons why he came. As a person, he’s fiercely competitive. Speed is the expression of competitiveness. Put everyone behind you: any way you can. I push him in another direction I tell him we’re fastest, but let’s also try to win the championship”.

That victory is not far off. If it hasn’t happened, it’s been, Elio says, “a little bit bad luck and also because we weren’t geared up properly. We just weren’t technically prepared enough, there was insufficient testing.” Lotus is feeling the pinch? “You say that, not me” grins Elio. “But we are a small team now, we’re not in the same league as Ferrari or Renault. There was a lot more money when Colin was around. We’d make a car, Colin would look at it and say: ‘I don’t like it, get rid of it.’ If you pointed out how much it cost, he’d say: ‘What do I care how much it cost’. Today, our racing is done with a pocket calculator in hand. That’s Peter Warr’s skill: with not much, he’s put a lot together.”

From outside, it looks as though Lotus has a winning car; yet it doesn’t win. Why not? “We get the most out of very little,” answers Elio. Quite naturally, one is led to discuss drivers in this context. Nigel Mansell in particular. Has he the capacity to win for Lotus? “Nigel’s good” answers Elio charitably (he was to be less charitable after the race). “He’s just a little limited in some ways, he doesn’t understand his own capacities.” There are limits to that understanding, that come from Nigel’s background. That makes for difficulties of communication between the two men.

“I don’t know if he suffers from a complex in my regard,” explains Elio “I have made many efforts to reach into his mind, to make things better between us, which is important for the team. I remember with Mario, when again we didn’t have the best car in the world: Mario would say, look, you put in such-and-such a time, and I’ll do the same; otherwise, they’ll never change this car! That was rapport. I don’t have that with Nigel, not since he first came on the scene and was still a boy. But when he came third in Zolder, his first result, it was like flipping a card; he became a completely different man. It was like a transformation. And I can understand it because he got that result coming from nothing. He’s not made of the same stuff as me. For me a third place is fine, it’s beautiful; but perhaps I can take it more in my stride that Nigel can.

“But from then on, he changed. He started to lie to Chapman, about all sorts of little things. It became like the thing between Mario and Ronnie. It reached the point where we literally no longer talked to each other; he would come into the motor home and say one thing and I would say another. It wasn’t good scene. Then came Canada, where he was behind me and flew by me and eventually had a bad accident. After that race, I no longer wanted a psychological war with him. It was as though it could actually hurt him if I did so. I didn’t want the responsibility.

We sat down together and tried to trash it out. But he has a complex. Now, all drivers are liars in part, we all try to hide things, but Nigel has a real complex on that score. It is a sign of weakness. And it’s useless to lie: the engineers know who’s telling the truth. Sometimes, I think it’s the people around him. I know that he’s always very tense, as though there was this huge pressure on him. As though, whatever happens, he’s still missing out on something. Perhaps because he’s not yet won his first race. That I can understand. But I don’t think that’s an excuse. He should improve, change. But underneath it all, I like him, and I respect him. I’ve seen him evolve already. It’s slow, but it’s constant.”

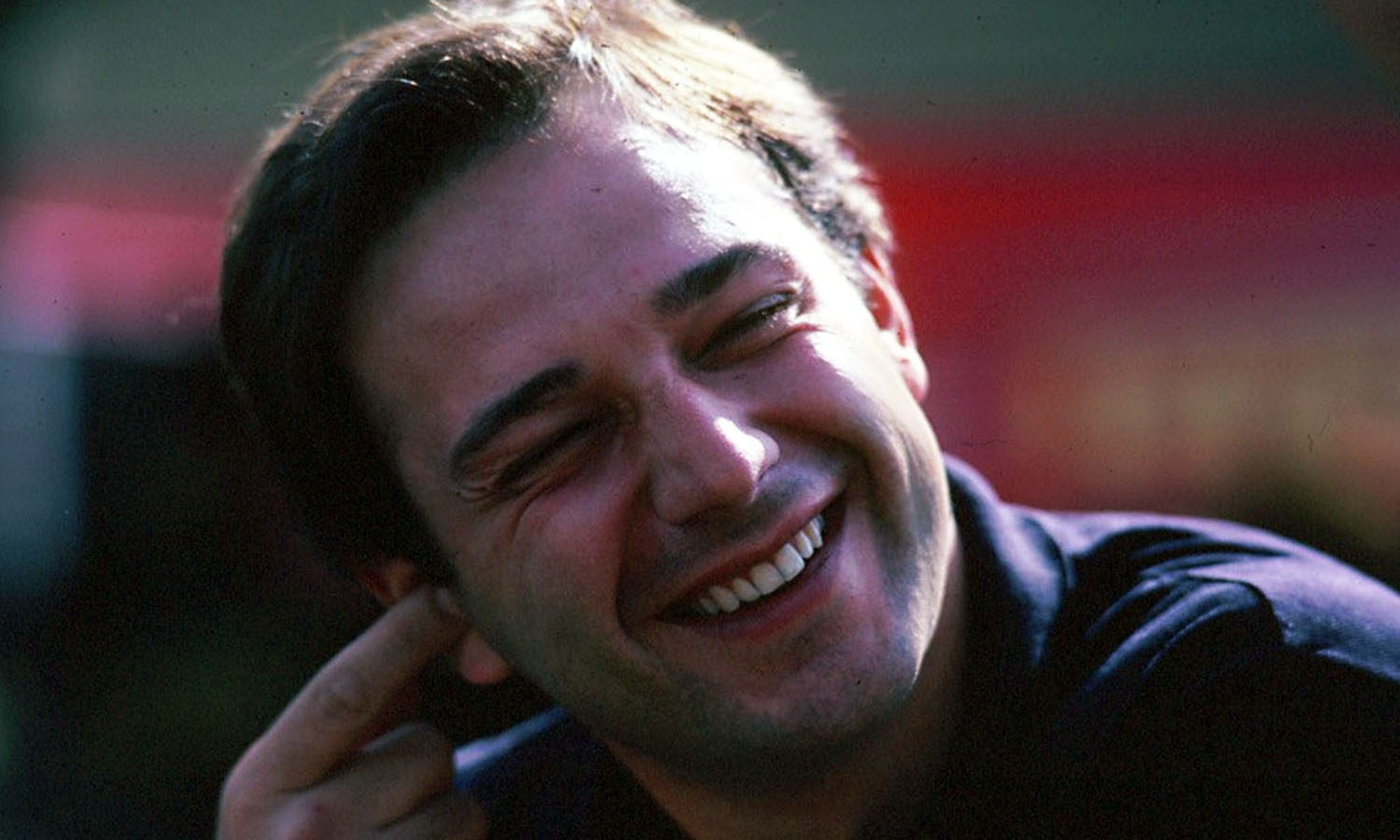

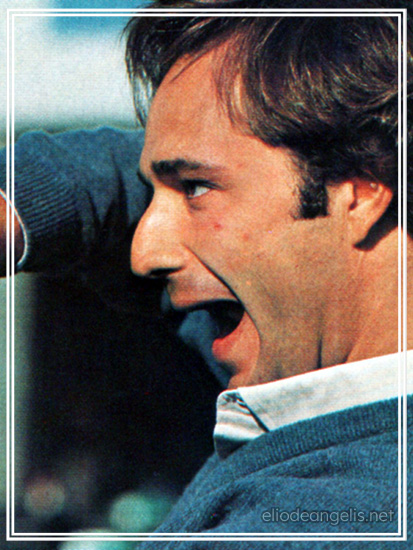

At which point, since we’ve been talking about Nigel’s defects, I asked Elio what his were. He was quick to answer: “Too much ambition. And a little laziness, which I could do without. Now I keep the laziness out of racing. You can only really rest, anyway, when you’re happy. After I won in Austria, I spent the finest week of my life. I didn’t sleep for a whole day. I wasn’t sleepy. And then Italy beat Germany in the World Cup the following week! I was on Cloud Nine.”

During this point, Ute chimes in, away from her usual quiet reserve. To tell us that the present German Football team is a disgrace. It is.

We all agree then. On something. Because on Elio the man and Elio the driver, whatever his position in the Championship table, there will always be disagreements and ambiguities. It is as though the man came himself from a different world to most. A world of greater ease. For most, hunger is what makes men succeed. And people think hunger is external. That it’s wanting something – money, success – that denied to others. But hunger is also internal. It’s wanting to know who you are and have people see what you are so clearly that they accept your own definition of yourself.

With music, money, sun and sea, all Neptunian signs and manifestation, Elio is likely to remain his own man and serene. But last year, Iron entered his veins. Or he wouldn’t have talked so freely. Nor raced half so well.

© 1984 Grand Prix International • By Keith Bosford • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended