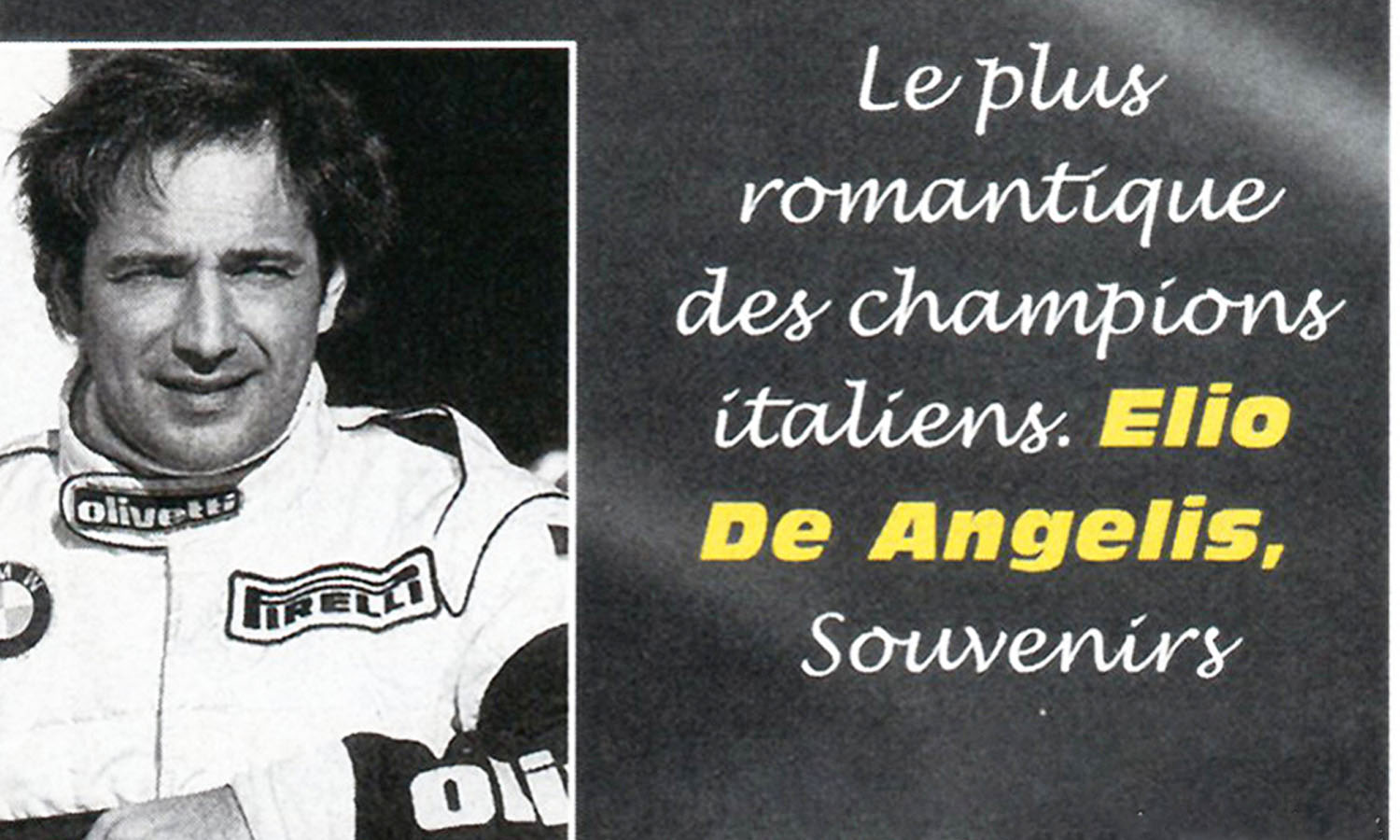

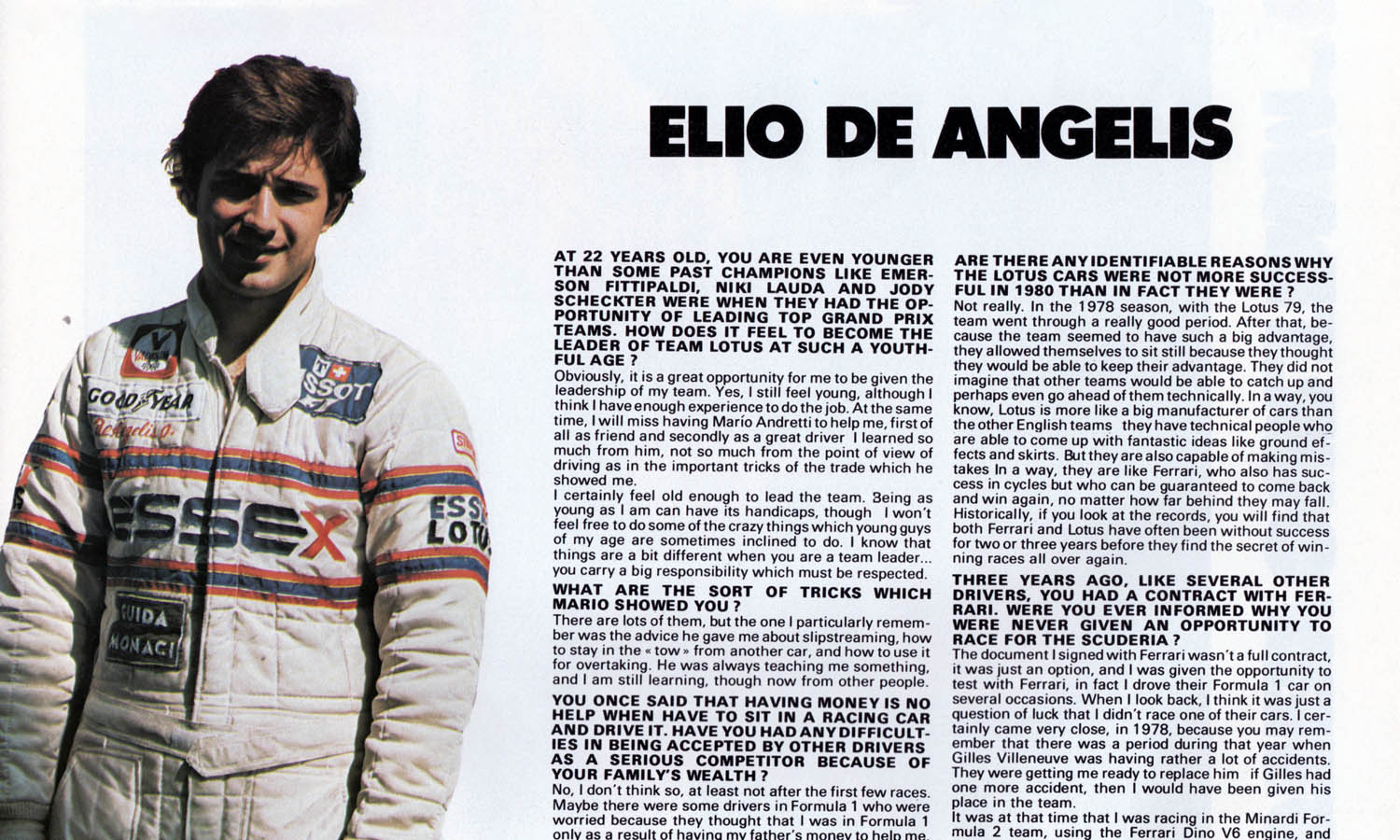

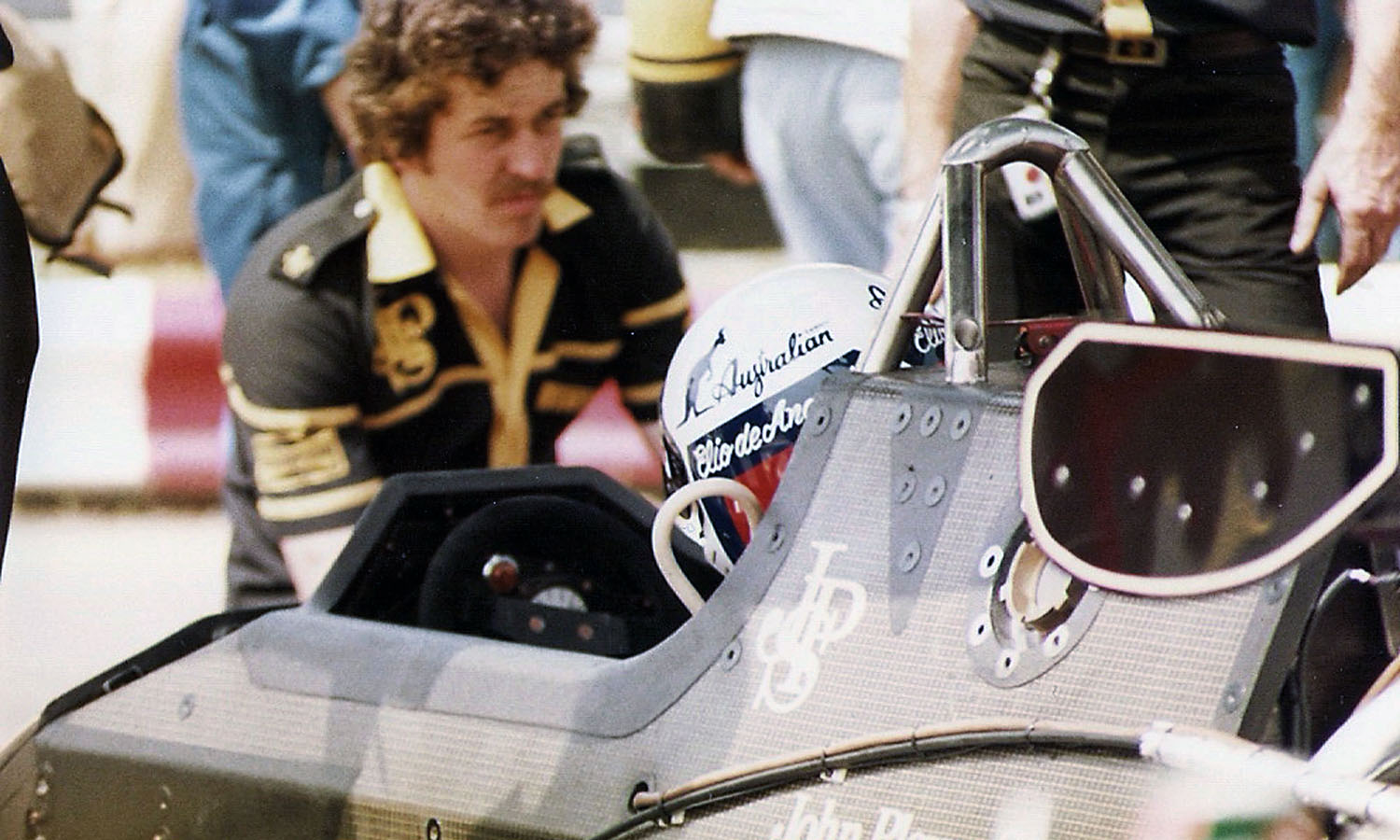

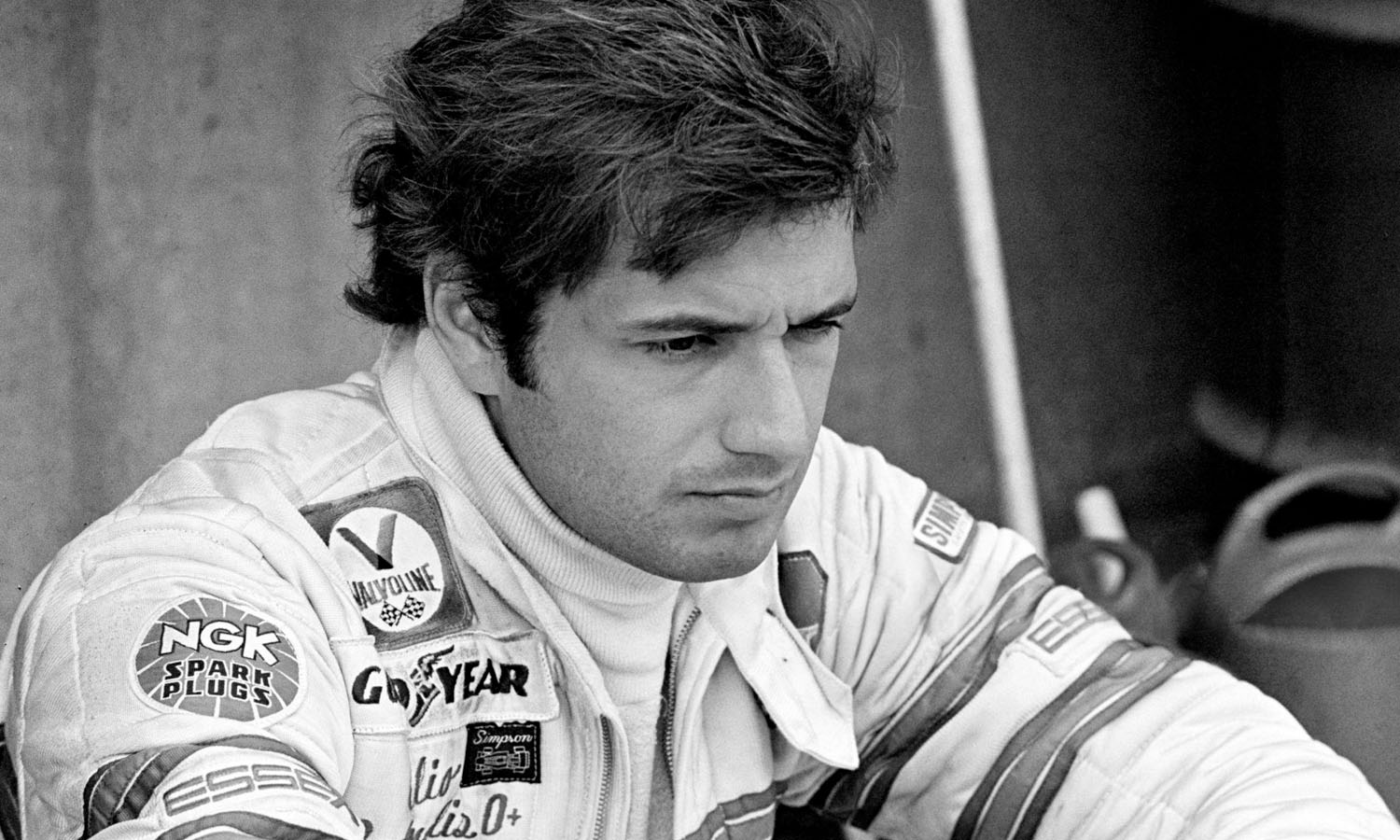

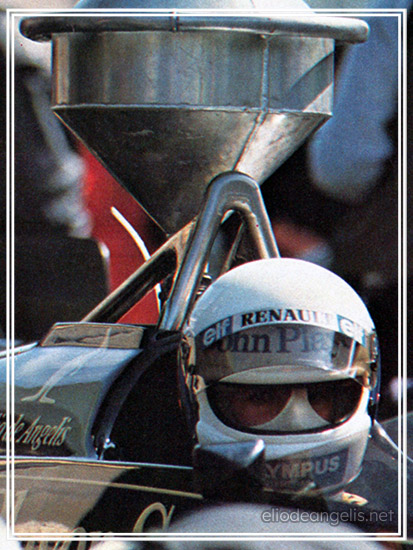

In Formula 1 terms, the love affair between Lotus and Elio de Angelis was a long one. Piquet may have spent more time at Brabham, and Laffite stayed longer at Ligier, but six years at Lotus suggests a lot of loyalty from a talented youngster who was still barely 22 when he drove his first race for the british team.

When Elio de Angelis joined Lotus in 1980, he and Colin Chapman were a mutual admiration society. In this wealthy but talented young man, Chapman saw the promise of patrician values coupled with Latin fire and a desire to prove himself in an environment where money is no substitute for talent. De Angelis saw Chapman as a designing genius who wished to nurture and protect him. The alliance endured between team and driver even after Chapman’s sudden death in December 1982. But on an afternoon in June 1985 it all fell apart.

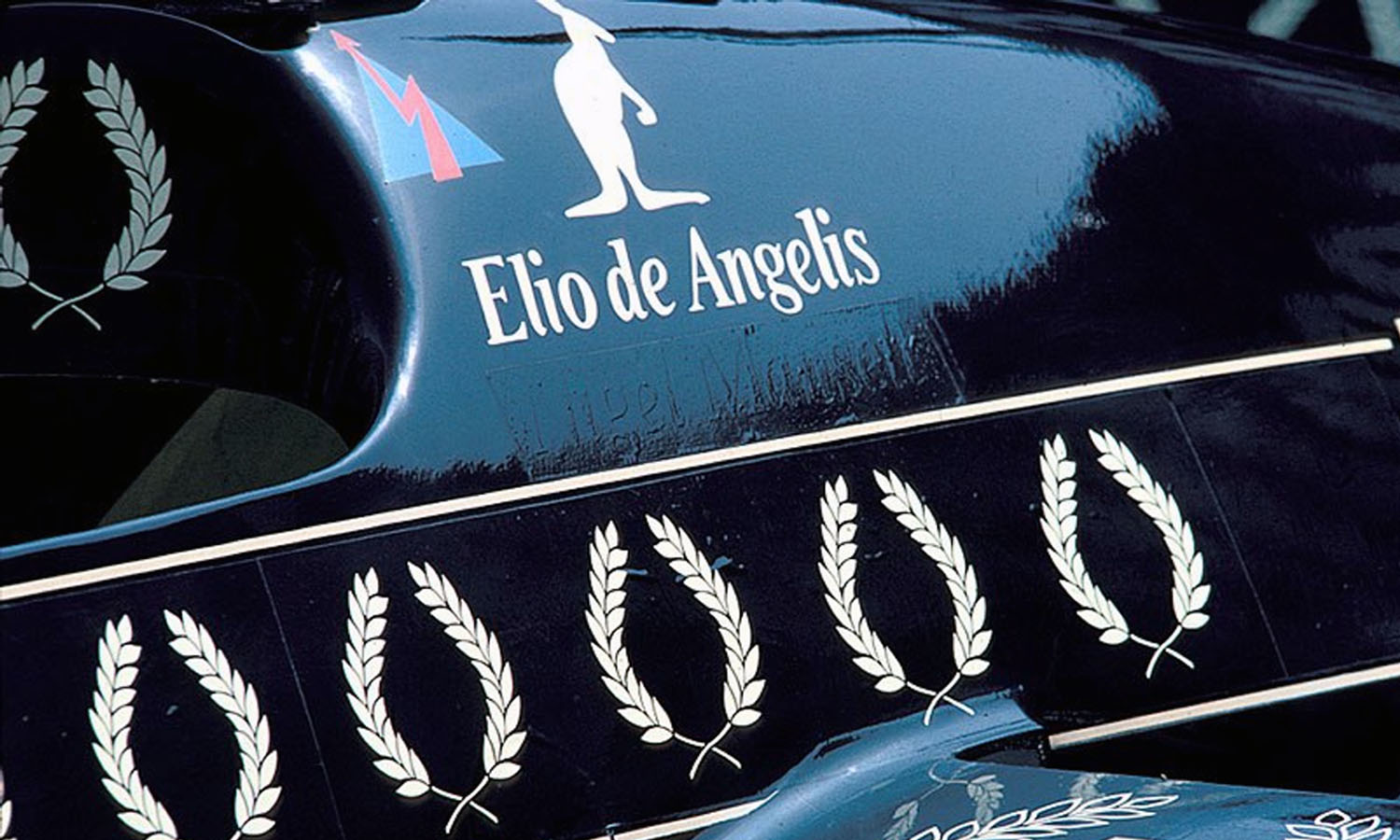

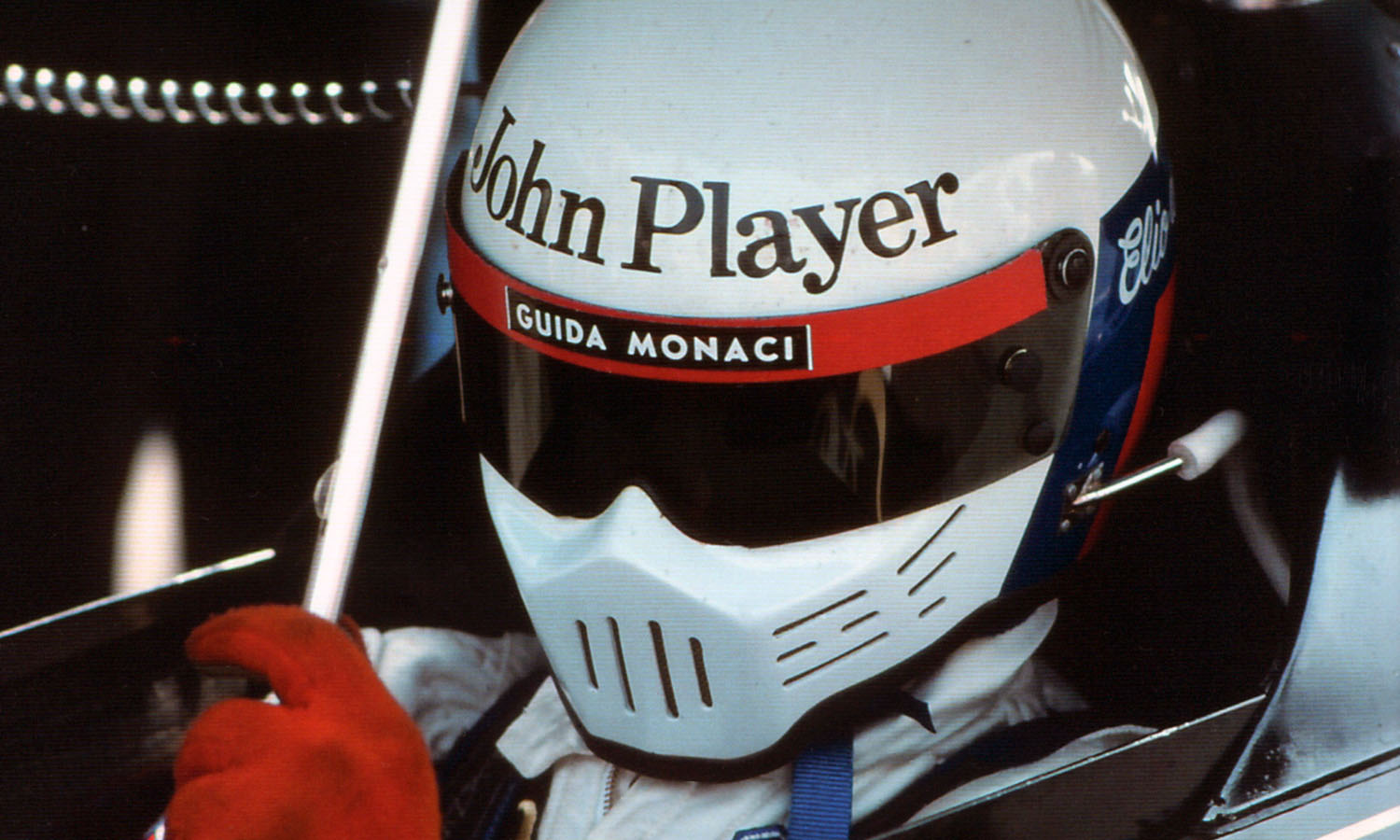

The liaison lasted through some exceptionally tough times. There was the period in 1981 when the budget dried up because the sponsor had been incarcerated in Switzerland, and it was Elio who lifted the team from the aftermath of that setback by narrowly beating Keke Rosberg to the line and winning the 1982 Austrian GP. That race provided Lotus’ first victory in four years, and it restored enough of John Player’s faith to sustain their substantial sponsorship for several more seasons, even though Colin Chapman’s death at the end of the year raised doubts about the team’s ability to survive without him.

I was left to trundle round like some new kid on the team

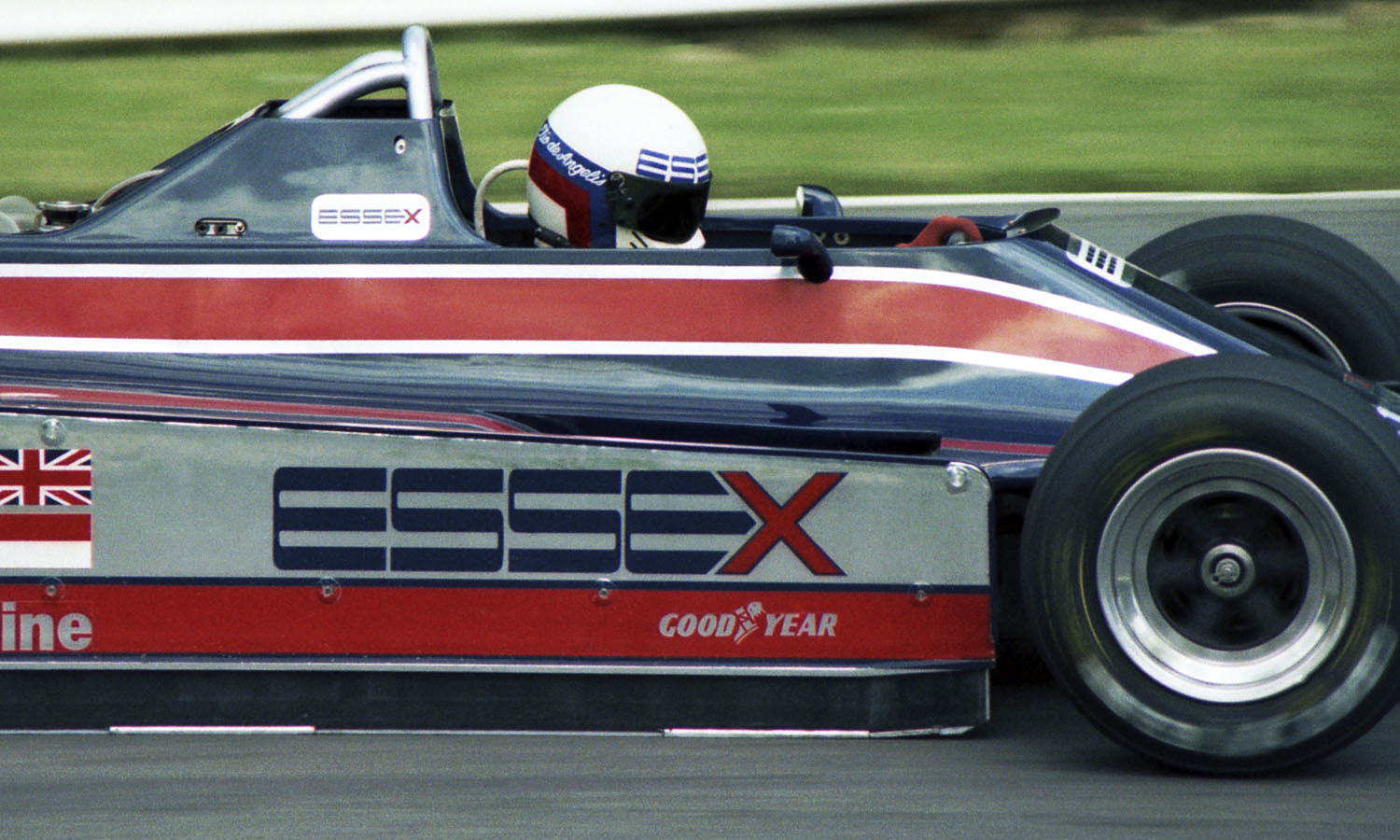

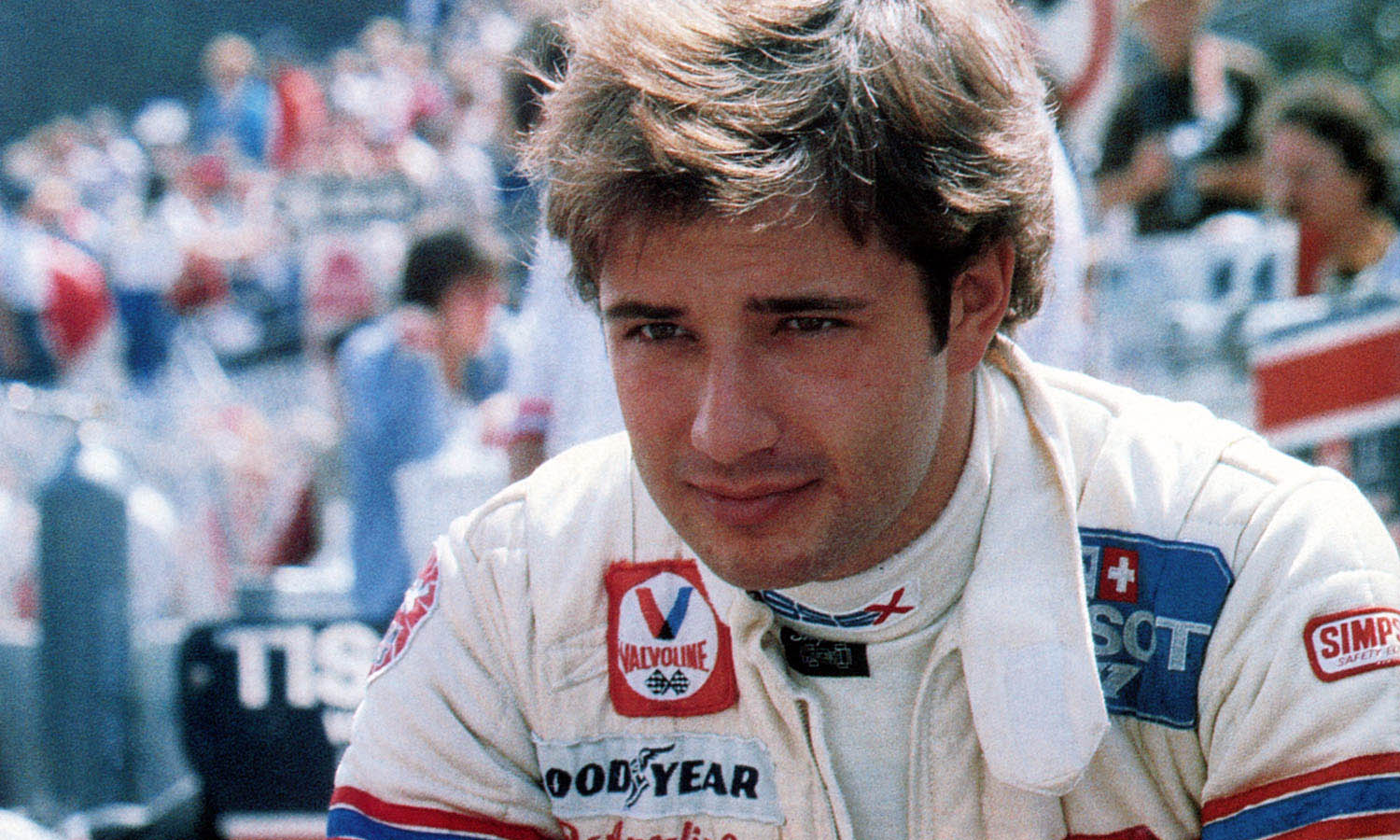

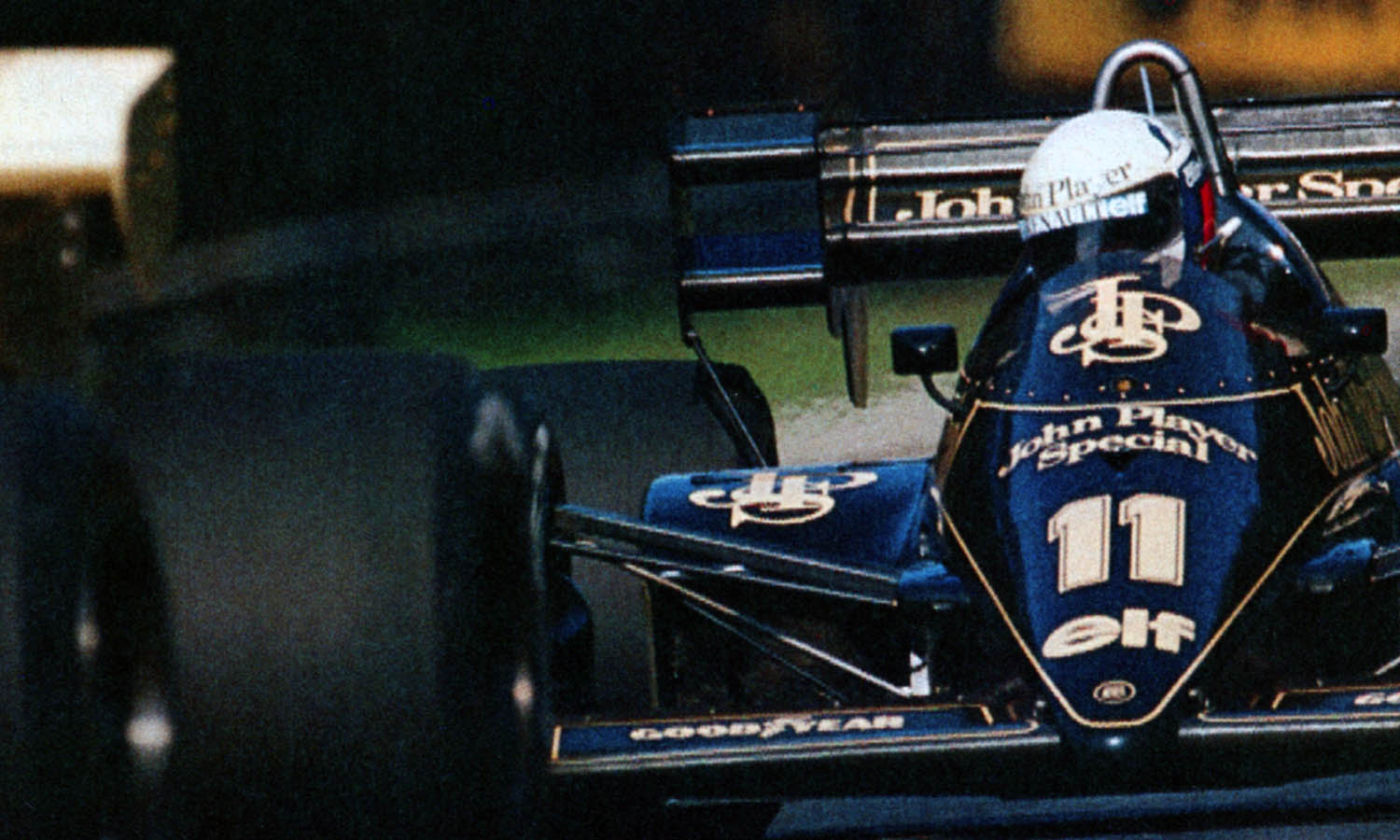

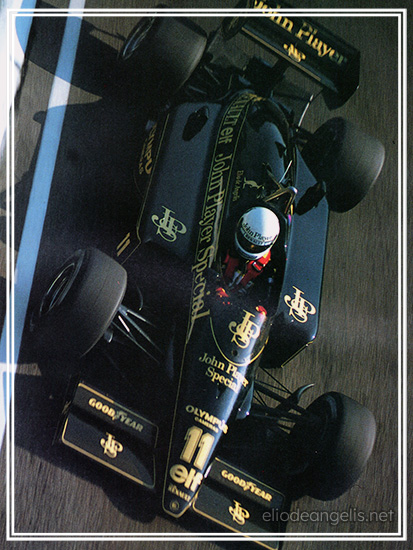

Lotus certainly needed its sponsor’s faith, for 1983 started appallingly, even for a team which had lost its leader and was to find itself at the bottom of the learning curve of turbo technology, further complicated by a switch to a then inexperience tyre producer. Following Gerard Ducarouge’s arrival as chief designer, the men from Hethel ended up by building three new cars in one year to re-establish their reputation and bring back the idea of racing enthusiasts getting into an event just to see one particular team take to the tarmac. Their reward in 1984 was to be the only team which even got close to challenging the red and white McLaren-TAG steamroller. It was only when mechanical failures ruined his finishing record that Lotus’ standard-bearer – de Angelis again – was obliged to give up hope of maybe even beating the McLaren drivers to the title.

It was in 1985, however, that de Angelis fell out of love with Lotus. Less than a month after winning his second GP for Lotus, after a race at Imola from which three front runners retired when their fuel expired in the last couple of laps, he brought his Lotus-Renault home to cheers of acclaim for his intelligence coupled with exactly the right amount of speed.

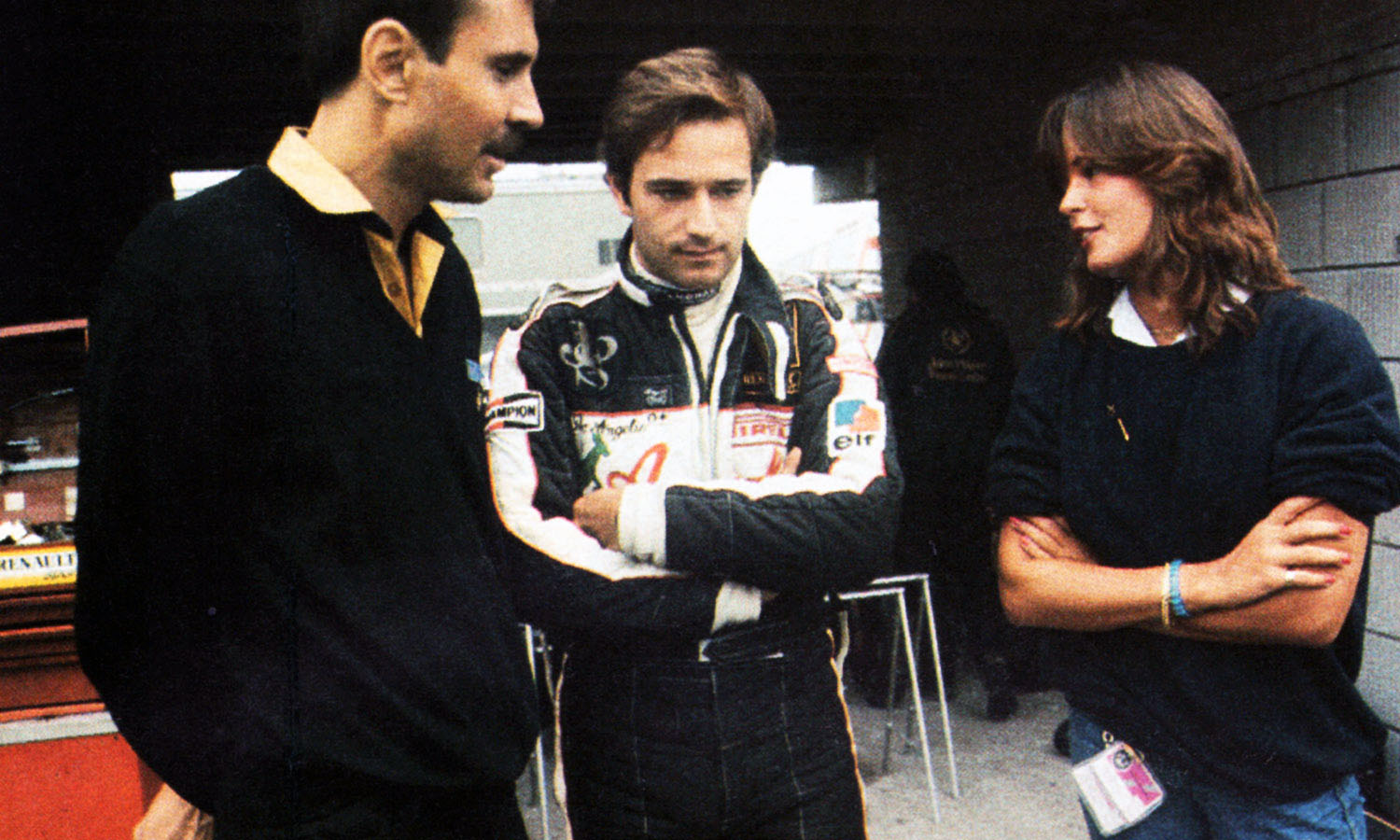

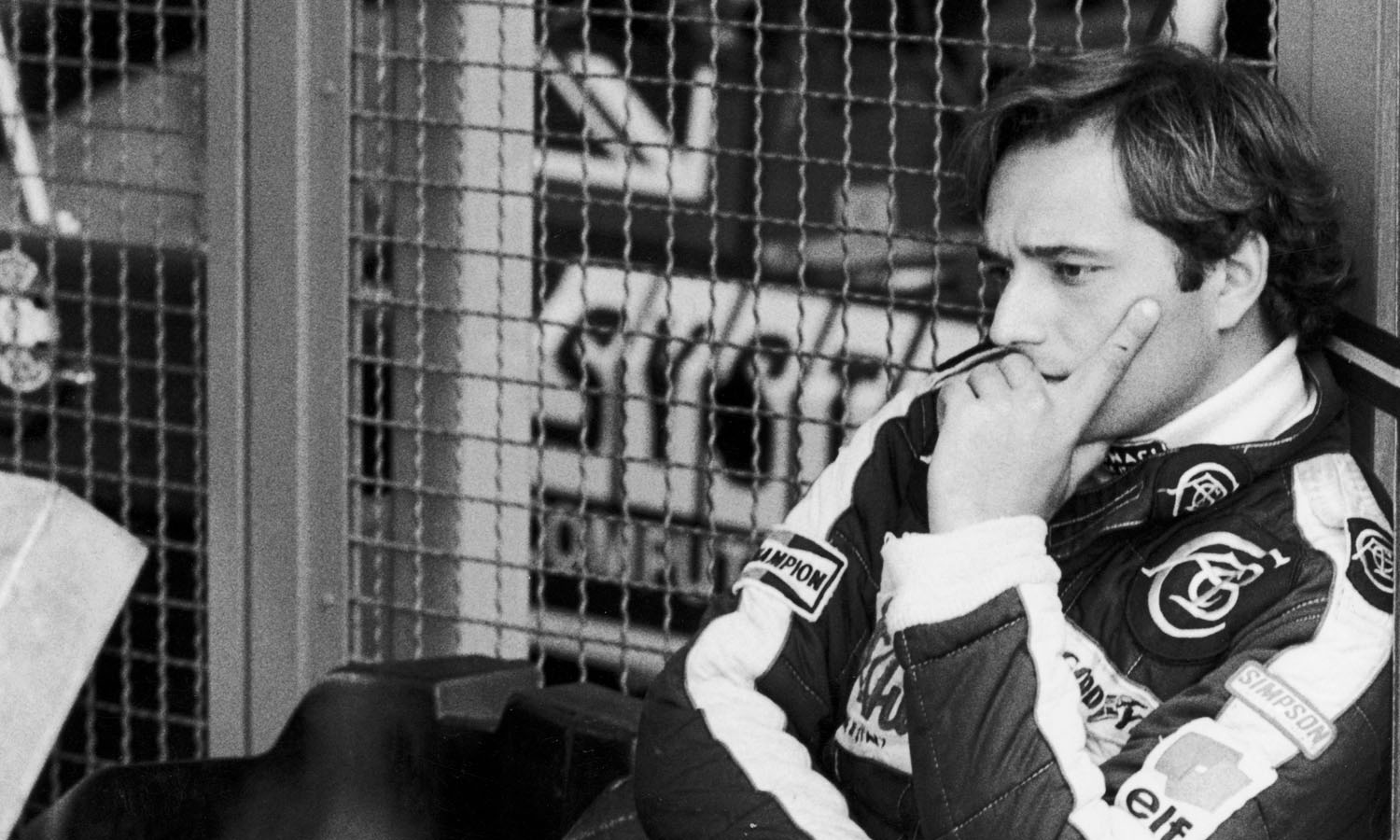

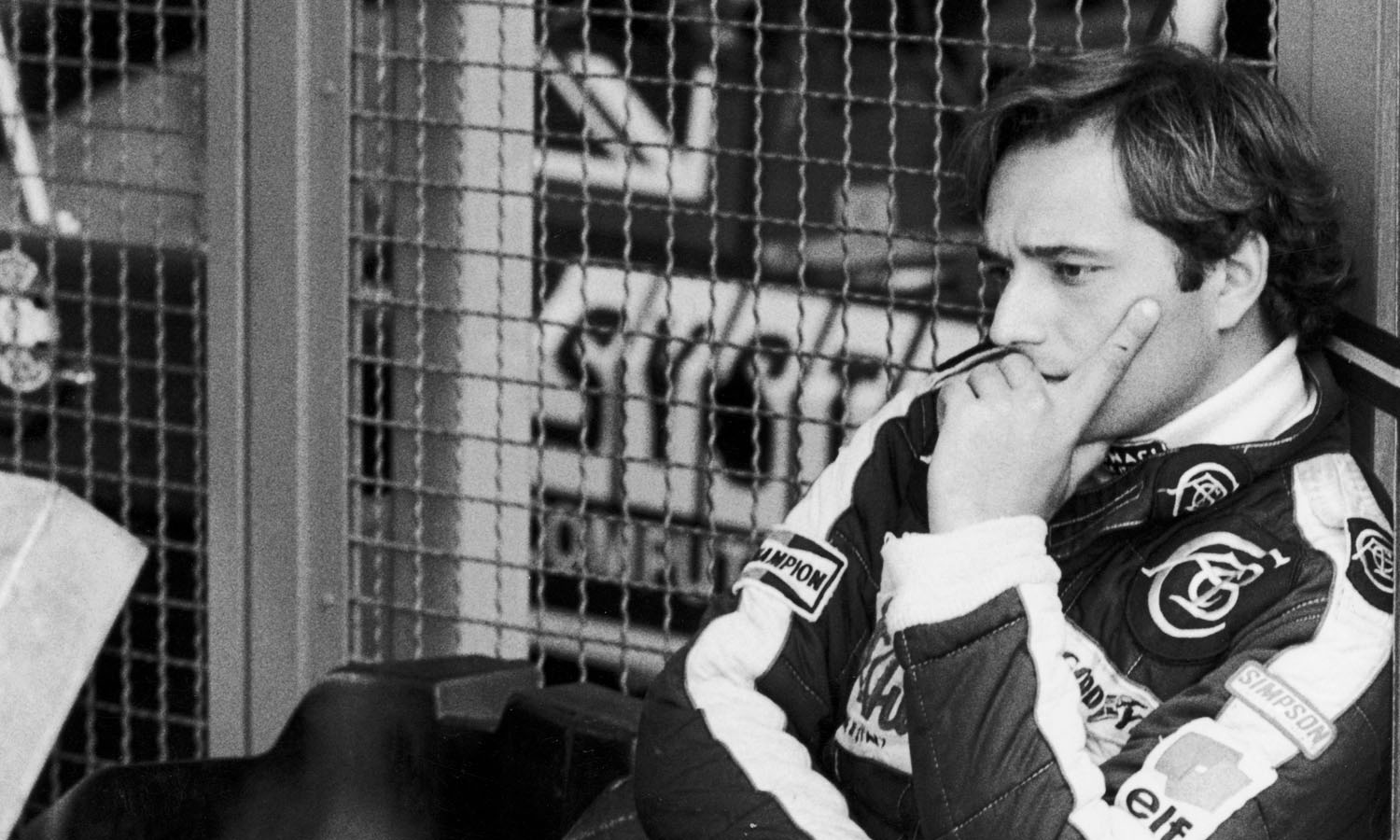

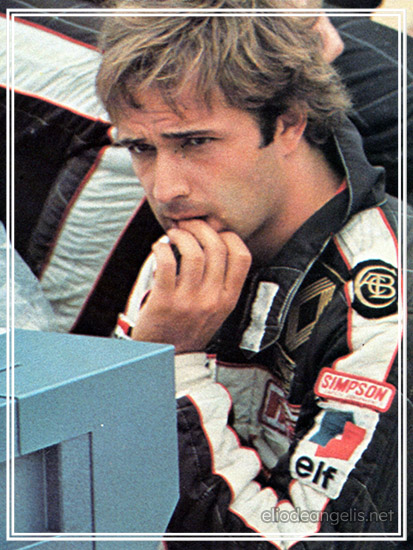

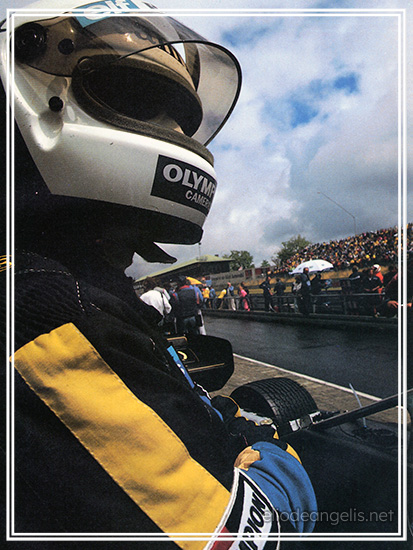

Nevertheless, he can pinpoint the day, even the hour, when disaffection crept into the relationship. Like so many affairs of the heart, there was another person involved, and as far as Elio is concerned, the Jezebel was none other than Ayrton Senna. The occasion was Lotus’ test session at Ricard, two days after the 1985 Monaco Grand Prix. “I was put on one side by Lotus. Starting right then, all they could think about was Senna. There had been some criticisms of the way I had been driving, because I had been more cautious than Ayrton. But the result was that I was leading the World Drivers’ Championship from Prost and Alboreto. However, when I got to the circuit they allowed me on the track just to do three laps. Imagine, on the day that I was leading the World Championship, and left to trundle round like some new kid on the team.”

“It was that same night, when I left the Ricard circuit, that I made up my mind to leave Lotus. From that moment onwards, as far as I was concerned Lotus was a chapter in my career which had been completed. I didn’t want to be treated like that ever again.”

His sense of rejection was all the more acute because he felt that Senna, for all his undoubted ability and speed, had acted in a fashion that was less than responsible. “I knew from the beginning that it was going to be a difficult year. I knew that he would be a difficult person, of course. I admired his determination and he is very determined – maybe too much. I felt that he found it necessary to show off his ability: even with the success that he had with Toleman the previous year, he was desperate to show that he had something more. Like the Arabs say ‘It is written’. There is something strong inside his mind: sometimes it is good for him, sometimes it is very bad. I think he found the ground at Team Lotus to build up his personality, with the help of Peter Warr. Ayrton became a protege to Peter, almost like a son, his own discovery. But he is very quick, I must say.”

Elio goes so far as to suggest that Senna’s attitude has been Machiavellian. He still smarts about the accident in the South African GP when Senna almost took him off the road in a stupidly fratricidal battle. Indeed, he says, “With Ayrton I had no difficulties until South Africa. I was so angry that I almost came to blows with him in the pits afterwards. And although we later shook hands on the matter, that was not the point. I think that was the incident which completely brought out his true character… I mean, with me it’s not a matter of saying whose fault it was, I am just saying that what he did was not right. He is a very strange guy, and he had a strange attitude towards me.”

Ayrton became a protégé to Peter, almost like a son

Those personal difficulties with Senna would never have arisen, Elio says, if the Brazilian hadn’t been encouraged by Warr. As far as Elio is concerned, in 1985 Peter Warr betrayed the Lotus team spirit in a manner which would have offended Colin Chapman. “There is nothing in common between their two methods. Chapman was the boss, a charismatic man with a strong personality second only to Enzo Ferrari’s. Peter Warr is a very ambitious man and a capable team manager, although perhaps he tries to do too much. It would not be difficult for Lotus to spread the workload more widely, and I don’t know why they don’t do that, because one day this situation could be very dangerous for the team.”

There was a feeling at Lotus in 1985 – which Warr never evoked in so many words – that Elio had become something of a plodder, less motivated than he should have been in comparison with his brilliant young teammate. Was it a handicap, I asked, for him to be a more mature, perhaps more reflective driver than Senna had been last year?

“Well, first of all I think that Senna had a fortunate year: he should have had more accidents than he actually had. That kind of driving doesn’t always pay off. I’ve had six years at Lotus, and I think that I’ve been crazy enough with this team. People tend to forget: I’ve gone jumping over the top of other cars, and banged wheels with people. I’ve done all those things. But once you’ve done it, you quickly realise that your chances of having a big shunt are increasing. As far as motivation is concerned, I have much more now than when I started. Now I know exactly what I want: I’m not doing this just for the pleasure of driving in Formula 1. That pleasure is what my Brazilian teammate was enjoying last year.”

Does that mean that there is more pleasure to be had from winning points rather than pole positions and fastest race laps?

“Look at Lauda. People say he isn’t quick anymore. But when the race starts, he’s really fast… And he’s been World Champion three times. Senna has been compared in Italy with Gilles Villeneuve, and me with Lauda. But I could had done two races in 1985 – Imola and Canada – like Senna did, by taking the lead and staying there knowing that there was no hope of the fuel lasting. I am unspectacular in the car because I work out the situation. Senna is certainly more spectacular than I am…”

As far as motivation is concerned, I have much more than when I started

In every argument, of course, there are two sides. Peter Warr himself, when questioned, emphasizes that Lotus policy in recent years has always been to supply his drivers with equal equipment. But when one of them consistently shows more speed than his teammate, then the faster of the two gets the better attention if it is not possible to supply them equally. As we shall see later, this argument certainly applied to Elio when his companion on the team was Nigel Mansell.

Perhaps Elio belonged to a different era of racing. When he joined Lotus, after a year at Shadow, he had already successfully sued Ken Tyrrell in a British court for having failed to honour a contract between them. In turn, Elio had been successfully sued by Don Nicholls of Shadow for walking out on a contract. But the young Italian had a strong sense of tradition, and when he joined Lotus as team mate to Mario Andretti there was never any suggestion of him wanting to compete aggressively against his partner, even if the American’s F1 career showed signs of slowing down.

Though Elio had regrets about leaving Lotus, they involve the people there with whom he was able to be close. Of these, the best known is certainly Gerard Ducarouge, who arrived at Hethel after the 1983 season had already started and managed to turn the disastrous technical situation around in a matter of weeks. I asked Elio whether “Duke” had always been cordial, and he replied exactly as you would expect from a gentleman like him.

“A friendship is a friendship; you should never consider it in terms of ‘ups’ and ‘downs’. Gerard is the sort of friend that I would have even if I was not involved in the business of racing. Professionally, a racing engineer must always give his attention to the fastest car on the team. For a series of reasons which should euphemistically be described as coincidence, Senna was faster than me. So, Gerard, who doesn’t get involved in politics, was put on to the faster car, which happened to be Senna’s. I would have expected him to have come down on my side within the team. It didn’t happen, but I can’t blame him. All the decisions at Lotus are taken by Peter Warr, and I found myself being left out both technically and morally. Gerard and I still have good relations, of course. Now I’m racing against him, of course, but I would have preferred to win at the wheel of one of his cars.”

I was intrigued to know whether Elio felt any irony in the fact that one year after Nigel Mansell had been made to feel so unwelcome at Lotus it was to be his, Elio’s turn, to feel like a gooseberry. Certainly his mechanic, Nigel Stepney who followed him from Shadow, saw (and regretted) the parallel. Elio doesn’t quite see things in those terms. “Although we received similar technical and psychological treatment, I think my situation was a little bit worse than Nigel’s. He had the advantage of being English, which made things better for him, easier for him to cope with what was happening. And sponsor-wise he had an advantage. Right to the end, he seemed to be enjoying his driving, while I must admit that I did not enjoy my last few races for Lotus.”

Perhaps Renault are beginning to get a complex about being second

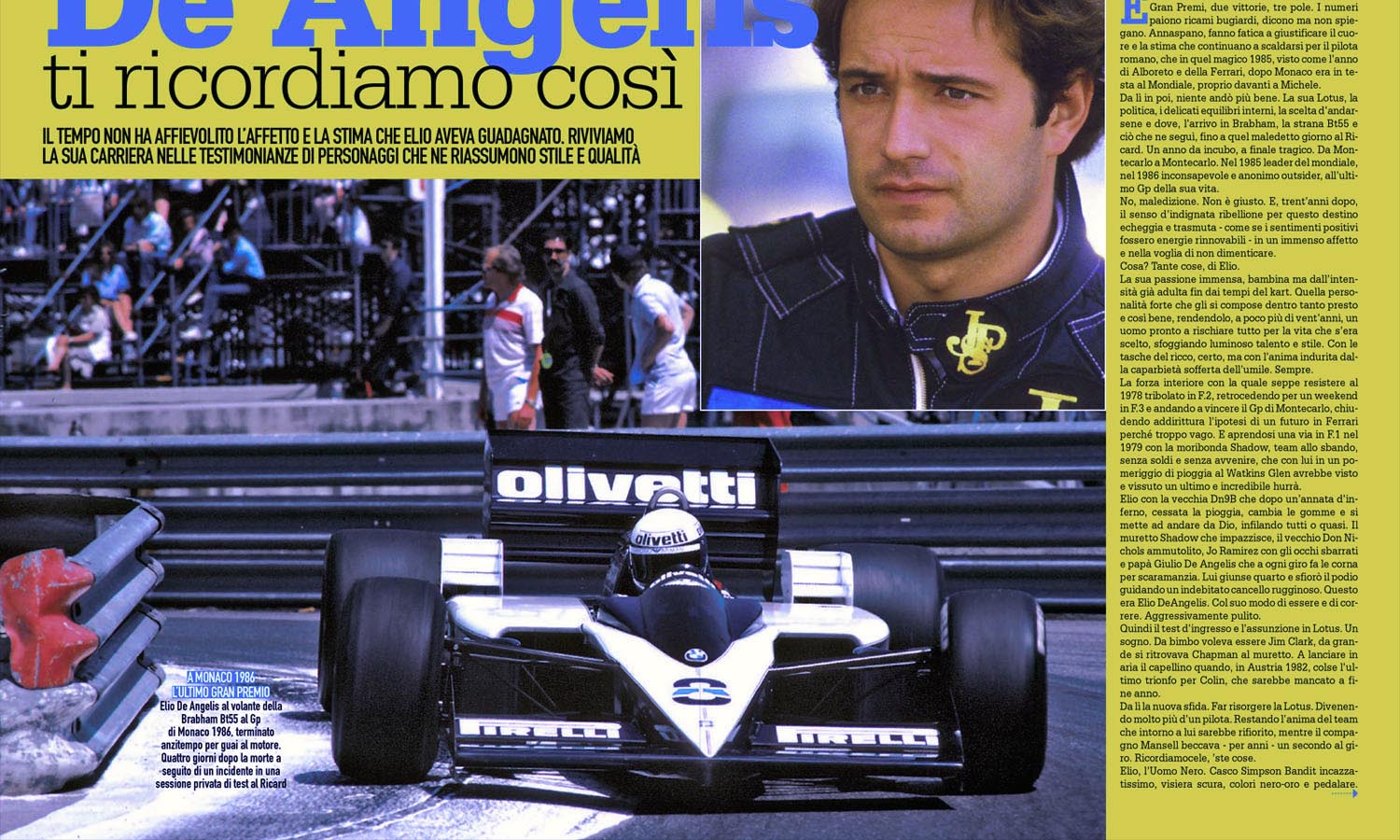

At the Austrian Grand Prix, following Nelson Piquet’s acceptance of an unrefusable offer from Frank Williams and Honda, Elio had signed an option to drive a Brabham. For many weeks there was no official confirmation of the deal, although Elio was confident enough. “I broke my links with Lotus when I gave a big dinner at Brands for the Chapman family, Peter Warr and Gerard, when I told them of my intention of leaving.” Clashes of personality were not the only irritants for Elio at Lotus in 1985. He had felt let down by Renault in 1984, only to suffer even more faults and failures in 1985. What caused so many problems? “It’s very difficult to say, because I am not a technician. The only thing I could clearly see was that they had too many teams to supply. Unfortunately, that cost them some Championships. They could not concentrate very well on one team. A serious problem at Renault is that they have been so close to success to many times that maybe they are beginning to get a complex about being second. Last year (1984) they let me down when there was something to be done, and maybe they could have done something more. Always ‘if’… But the fact is that if they had given us the works engine last year, perhaps the situation with McLaren would have been different. Maybe it’s a mistake which they will not be making again in 1986, because I heard that they will stay mainly with Lotus, plus one other team.” Those words, spoke before Guy Ligier arm-wrestled Renault engines out his buddy Mitterrand, imply one of the reasons why he is happy to be with Brabham.

“I think that Brabham is the only place that I wanted to go. If it was not going to be Brabham, it was going to be nobody. I am always looking forward: I would never go back. I always had a possibility for many years to go with Brabham, and this year I took it.” He started testing the 1985 car at Estoril in December, when he commented favourably on the power of the BMW engine and the improvements made by Pirelli with their tyres. The latter remark was important psychologically, for Elio did not spare Pirelli designer Mario Mezzanotte’s feelings after some less than wonderful experiences on Pirellis in the one year that Lotus spent with the Italian company.

I respect Keke and he respects me

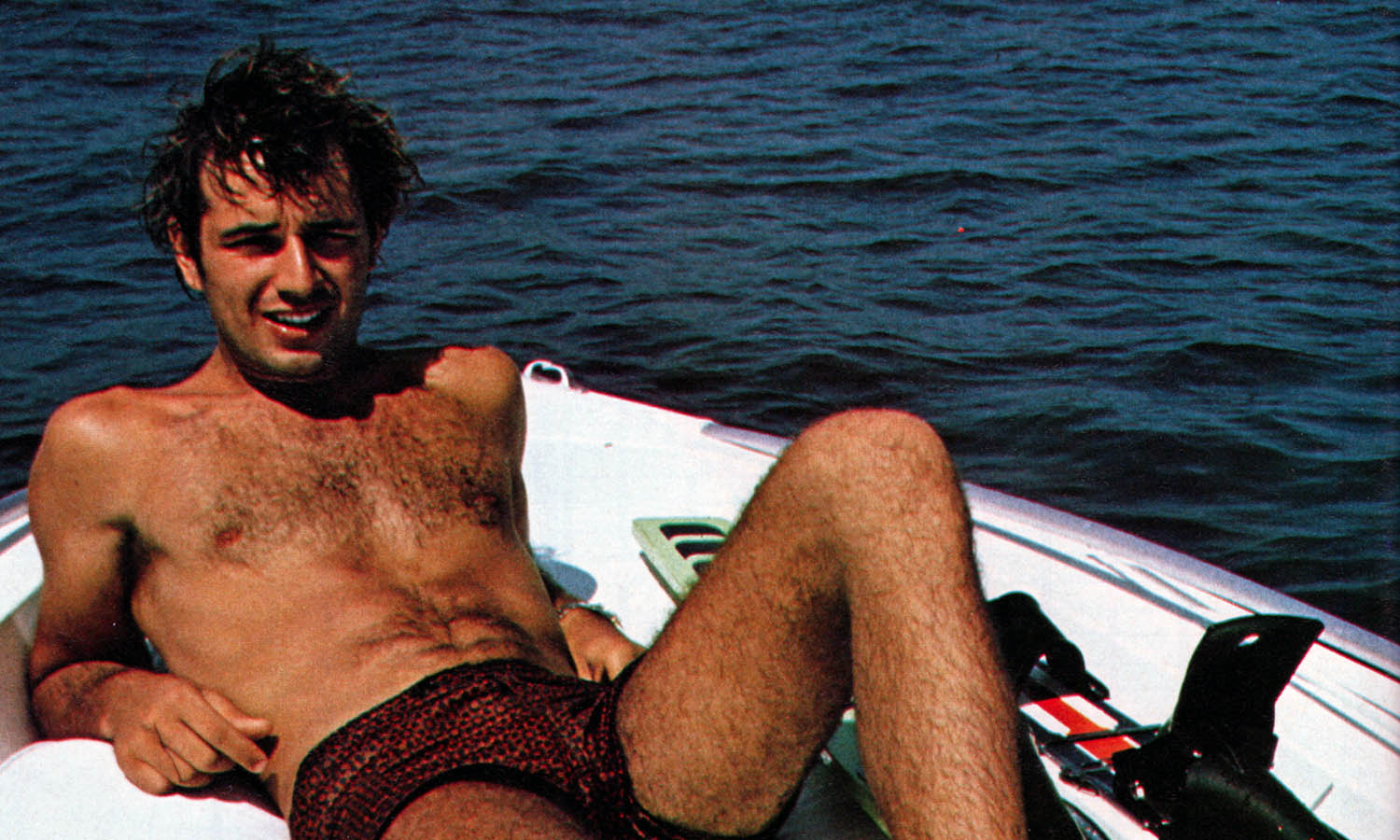

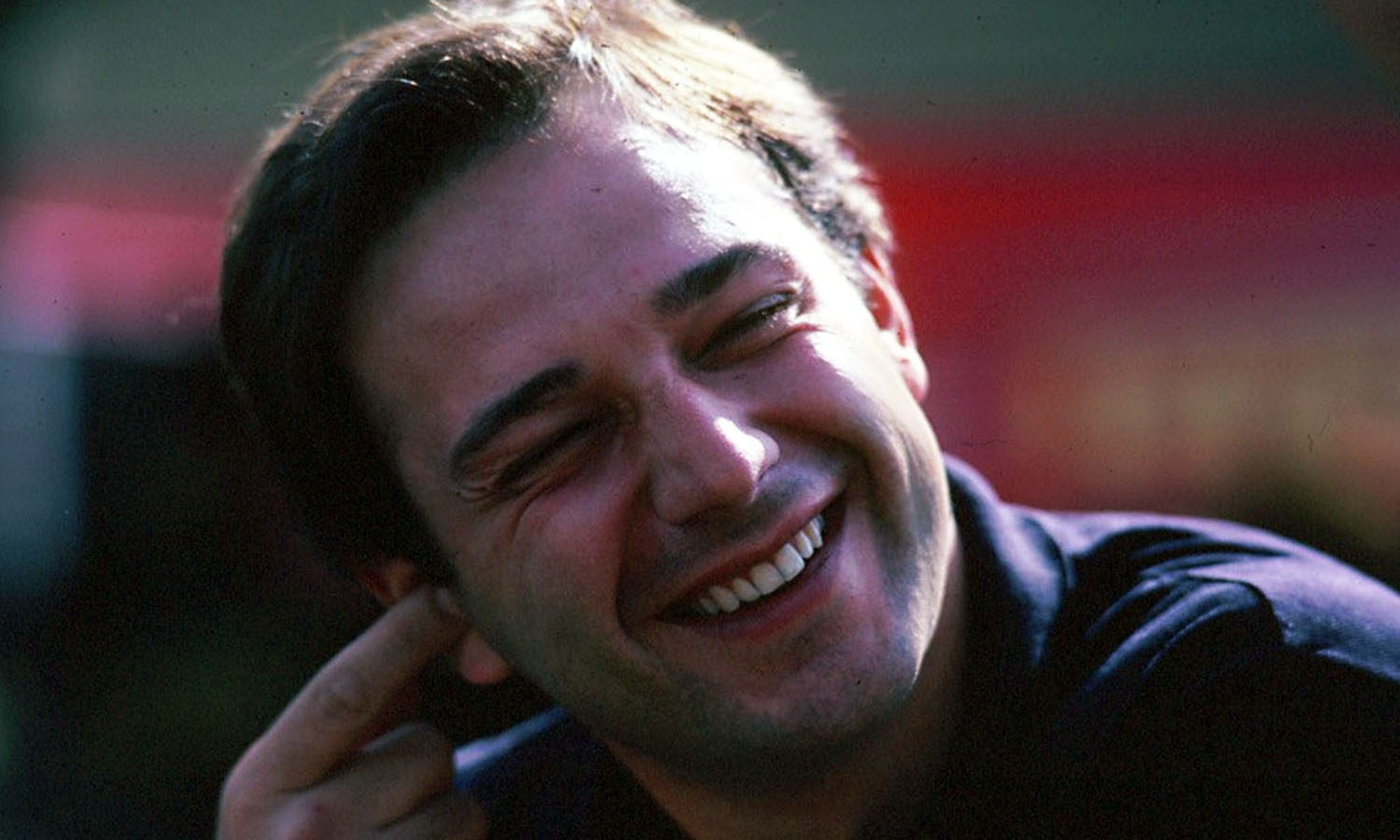

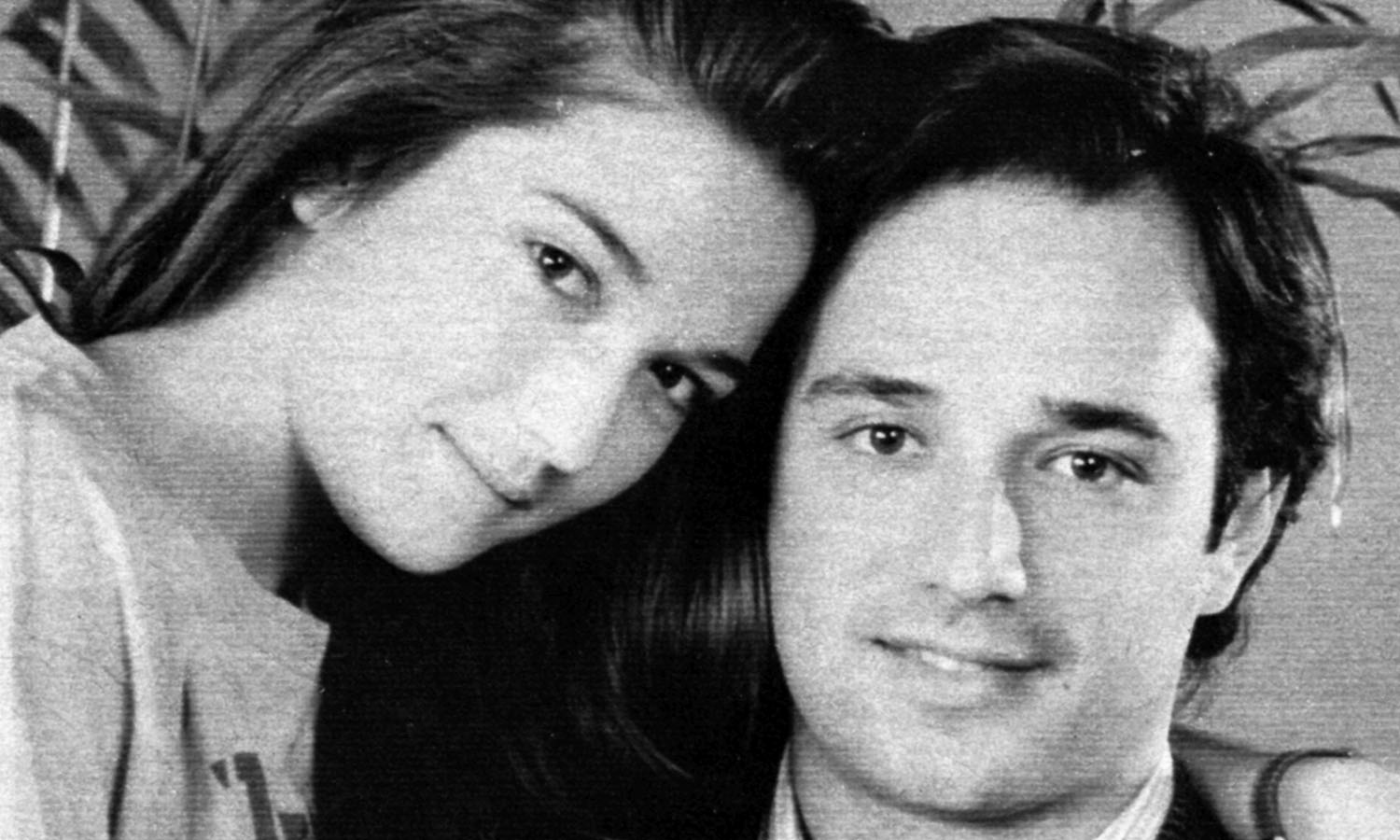

While waiting for the exciting new Brabham-BMW BT55 with its ‘lie flat’ engine and reclining driving position, Elio lives a quiet, albeit opulent life in Monaco. He spends a lot of time in the company of Ute, his German girlfriend, sometimes at her place near Heidelberg. She is a model but seems to spend more time with Elio than she used to. Grinning, she explains that a model, at 27, is beginning to get too old for many publications.

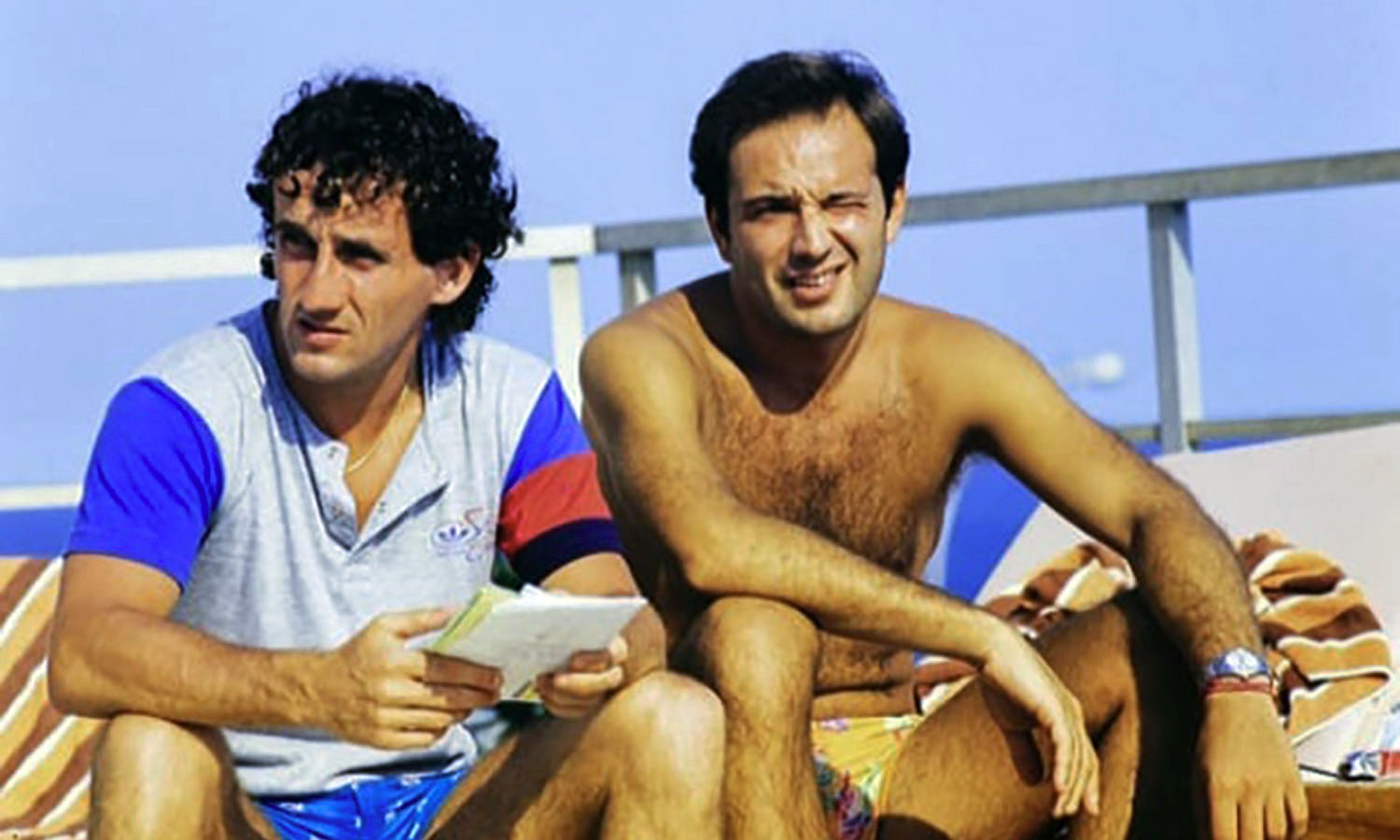

His family, one of Italy’s wealthiest, is in the construction business, yet the Monaco apartment is very small. “Very average” as he says, “in fact it is my only property, because all the rest is in the hands of my family.” He is friendly with Nelson Piquet “a very nice and very honest person” and even chummier with Keke Rosberg. “The main thing is that we respect each other: he respects me and I respect him, because for sure he is one of the quickest racing drivers in the world. We more or less grew up together in Formula 1, and we never had any problems together, we never had one hard word to say about each other. I like that, and we would like each other even more if we were not both involved in racing.”

He loves cars, although he’s not so keen on the bullet-proof limousines which greet him on the tarmac as he steps off planes in Italy, where all wealthy people are liable to kidnap attempts by political extremists. His personal collection includes the inevitable Mercedes (a 500 coupe) and no fewer than three Porsches, the marque for which he has a weakness that extends to a 928S and two 911SCs (a Coupe and a Cabrio). Apart from Lotus racing cars, incredibly the only Lotus which he ever drove was Colin Chapman’s own modified Esprit Turbo.

Nevertheless, when a new Lotus agency was opened up in Monaco just before last year’s GP, he went along to it’s opening, where a green Esprit was exhibited with his name displayed on its door in gold leaf.

Although he has tried flying planes, he has no intention of getting himself qualified as a pilot. “There are not really many routes available for private flying, it’s not as free as you might think. In a way, it’s a bit like being a taxi driver, because you can’t go where you want to go, someone else decides the route for you. I’ve done quite a lot of hours flying, enough to get a license, but I don’t want to take the examinations. I think it must be against my mentality!”.

I’m going to stop saying that I’m a good musician

His Love for music and a talent for piano playing are already well documented. They’ve even been exploited, because he was invited to play on German TV before last year’s race at the New Nurburgring.

“But I think that I’m going to stop saying I’m a good musician, because I want to concentrate more on my Motor Racing. It’s not that I’m not concentrating enough, but it’s something that gets in the way. I won’t say that I’m going to give up music, but I shall stick more to my racing programme. Still, I love music: I had a classical training and I only gave up because I didn’t want to end up playing in the Swedish Embassy or wherever. Now, I don’t want it to detract from my racing. Music is my second love, and I don’t think I would be satisfied with two loves in my life.”

I don’t think I would be satisfied with two loves in my life

The Brabham drive is clearly a “make or break” opportunity for his career, which will be less musical in 1986. His reputation now lies in the hands of Brabham designer Gordon Murray. A good car will ensure that Elio puts all of his time and energy into winning races. A dud chassis will cause him to lose interest very suddenly.

It is the opinion of many that we have not yet seen the best of Elio de Angelis, and a rivalry with Senna could make that particular combination of personalities a fiery one as they race against each other in a possible reckoning-up of old scores. It’s just one of the many scenarios to relish as the new season starts.

Certainly, Elio de Angelis is not sorry to face an entirely fresh prospect at Brabham in 1986.

© 1985 Grand Prix International • By Mike Doodson • Published here for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended