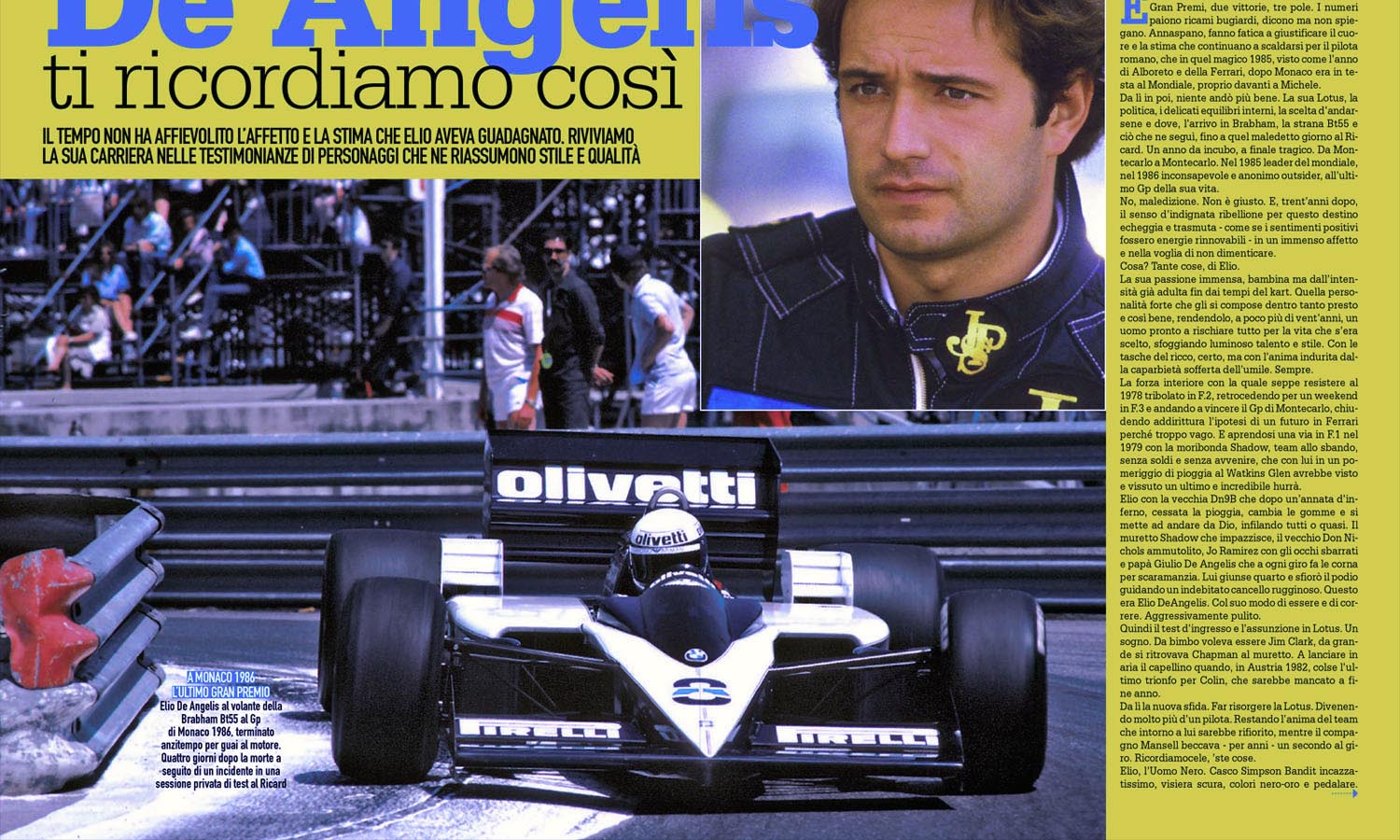

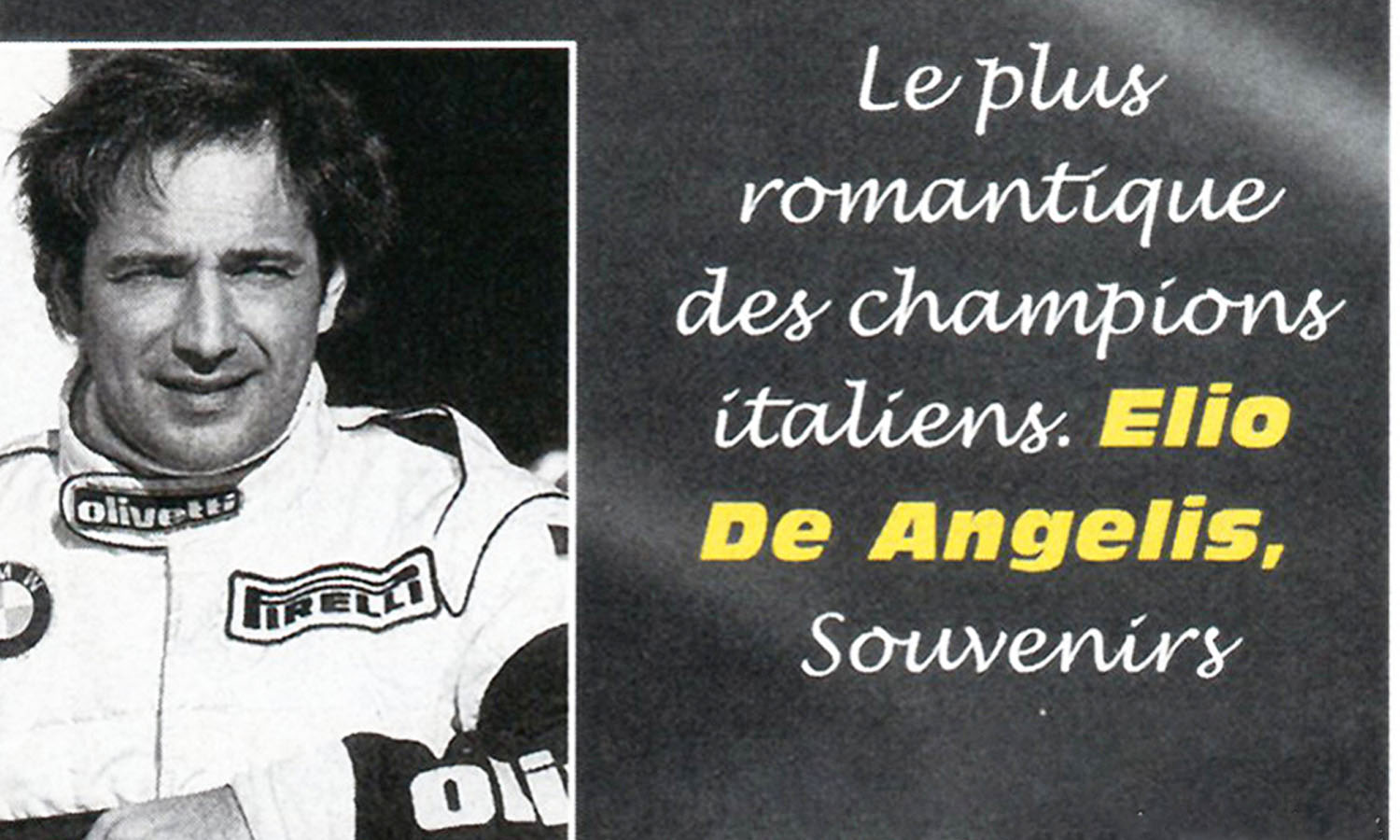

Smooth operator doesn’t come close... The only thing that Elio de Angelis ever miscued was his switch from one F1 team to another.

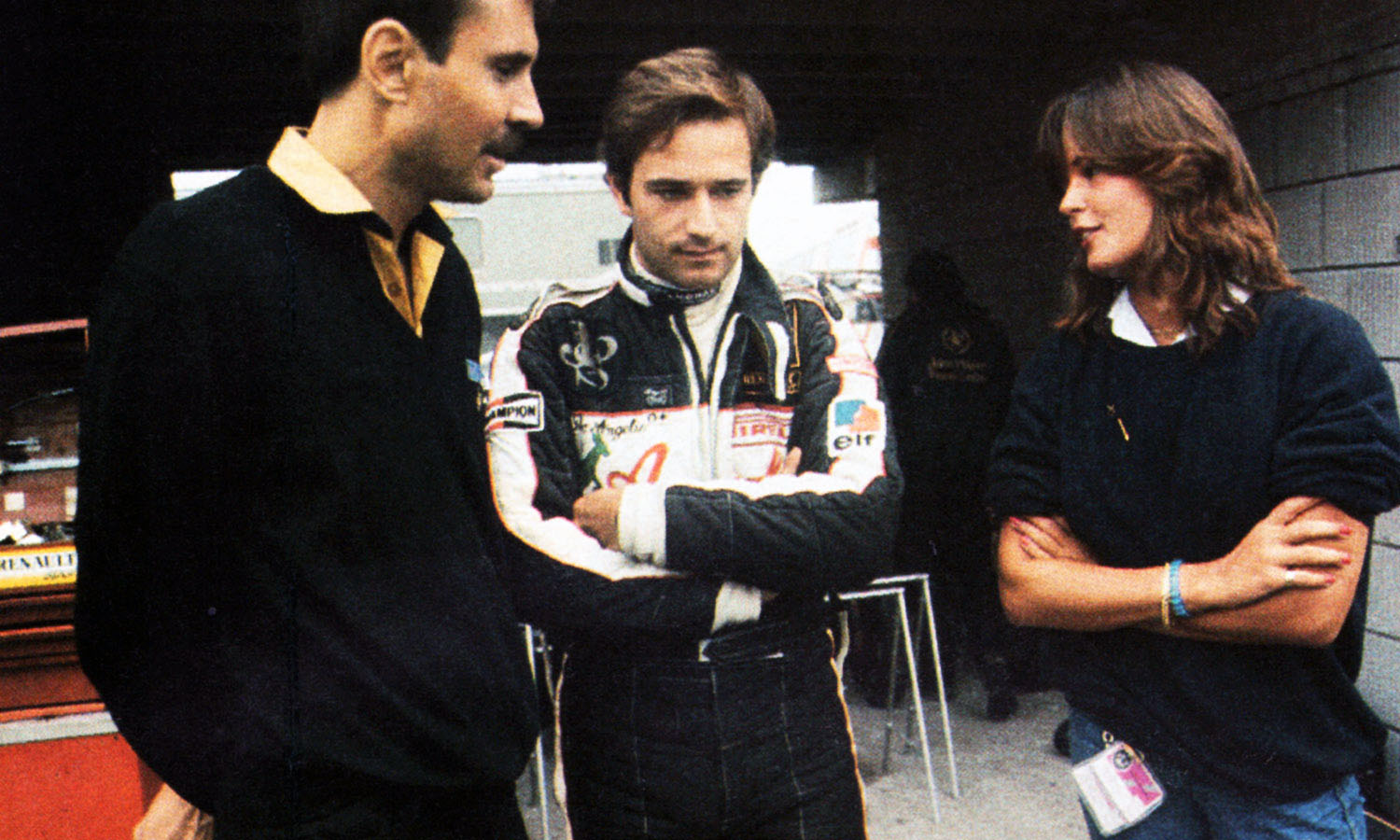

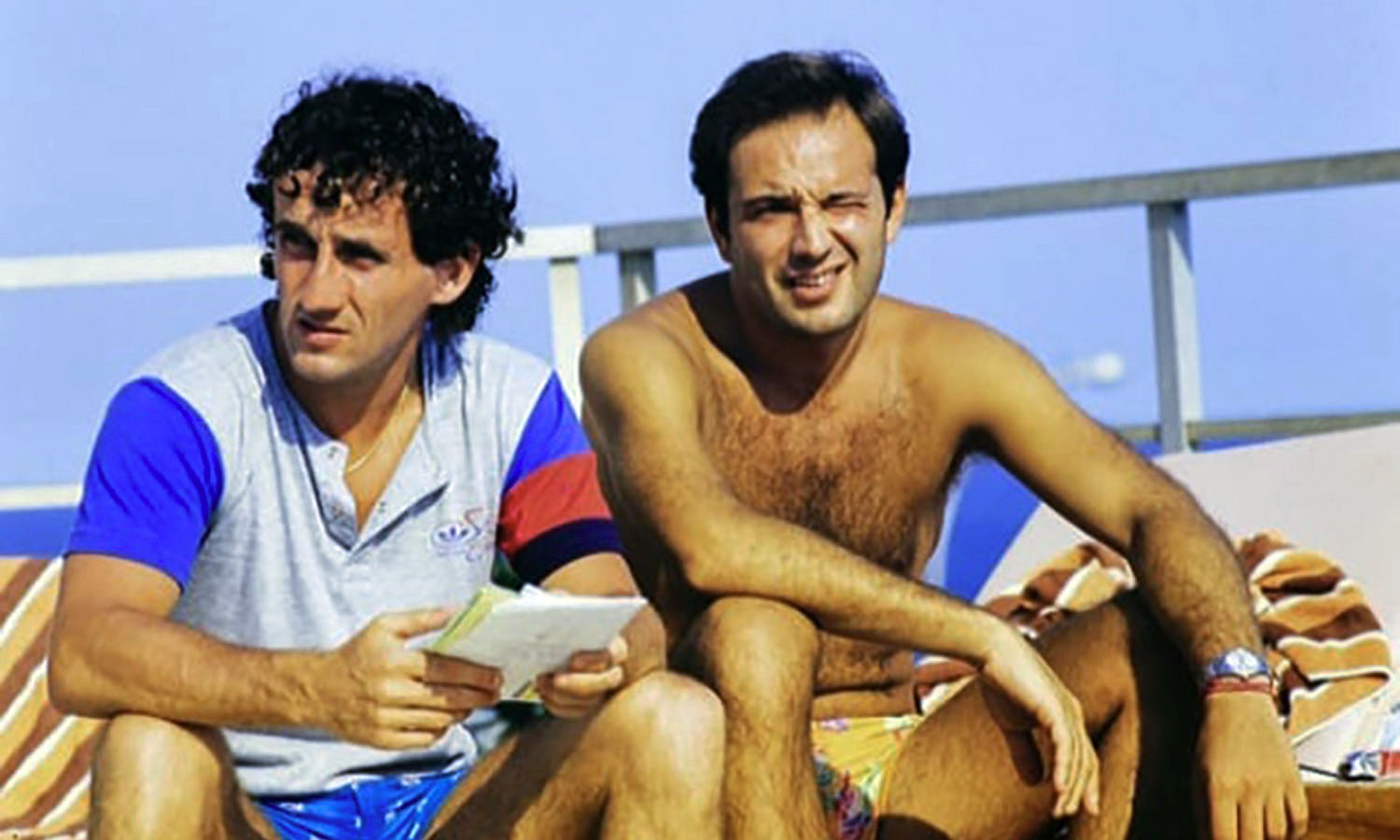

F1’s Fiat Pack – Eddie Cheever, Elio de Angelis and Riccardo Patrese – strode the pit lanes of the world in the 1970s and ‘80s. They all grew up in Italy; They all raced karts – for fun at first and then, when They were about old enough to walk, as if their lives depended upon it. All were talented; all moved in beautiful circles; all were successful. Eddie turned down a Ferrari drive at the age of 19 but went on to take nine F1 podiums and then to win the Indy 500. Riccardo raced for Shadow, Arrows, Alfa Romeo, Brabham, Williams and Benetton before retiring with six F1 wins and 256 F1 starts behind him.

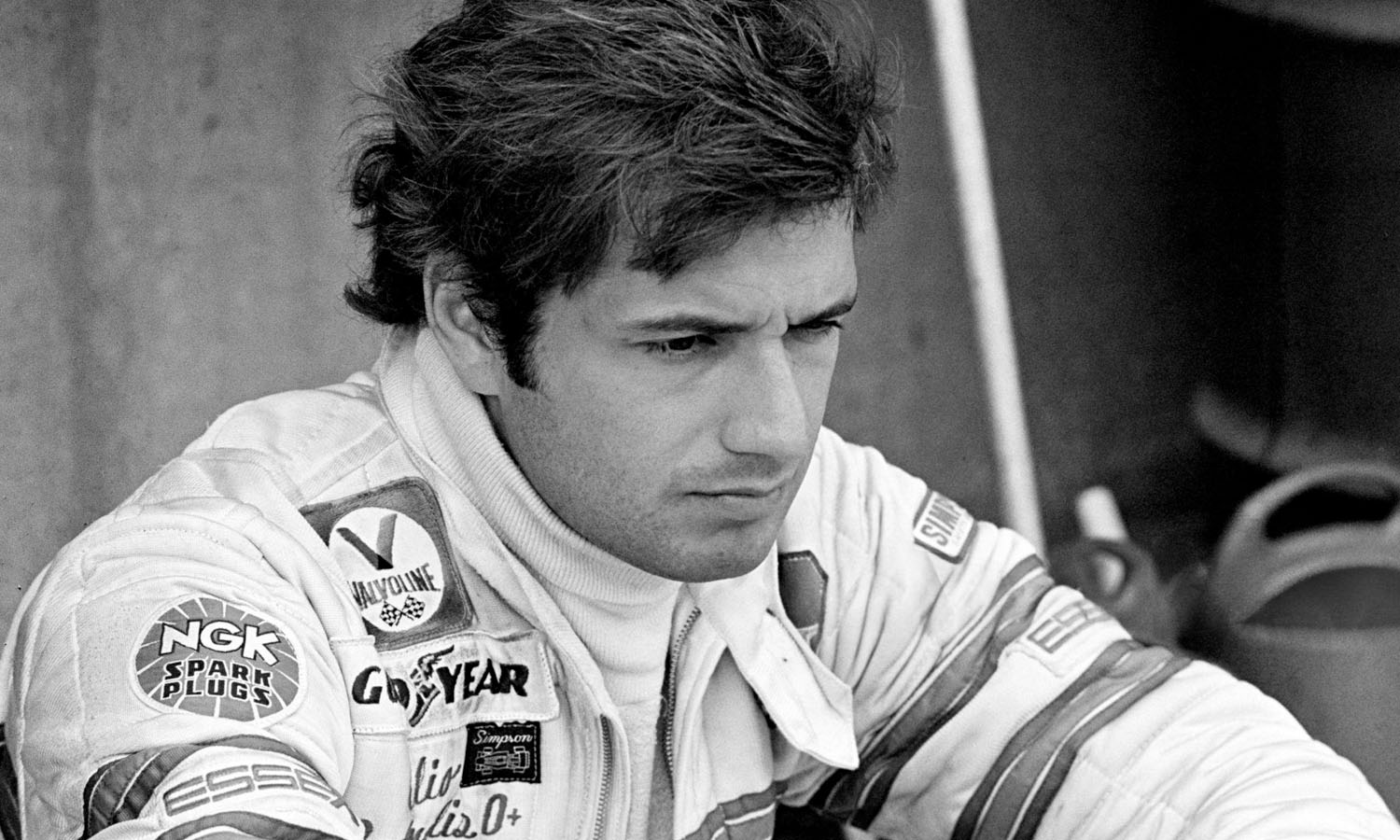

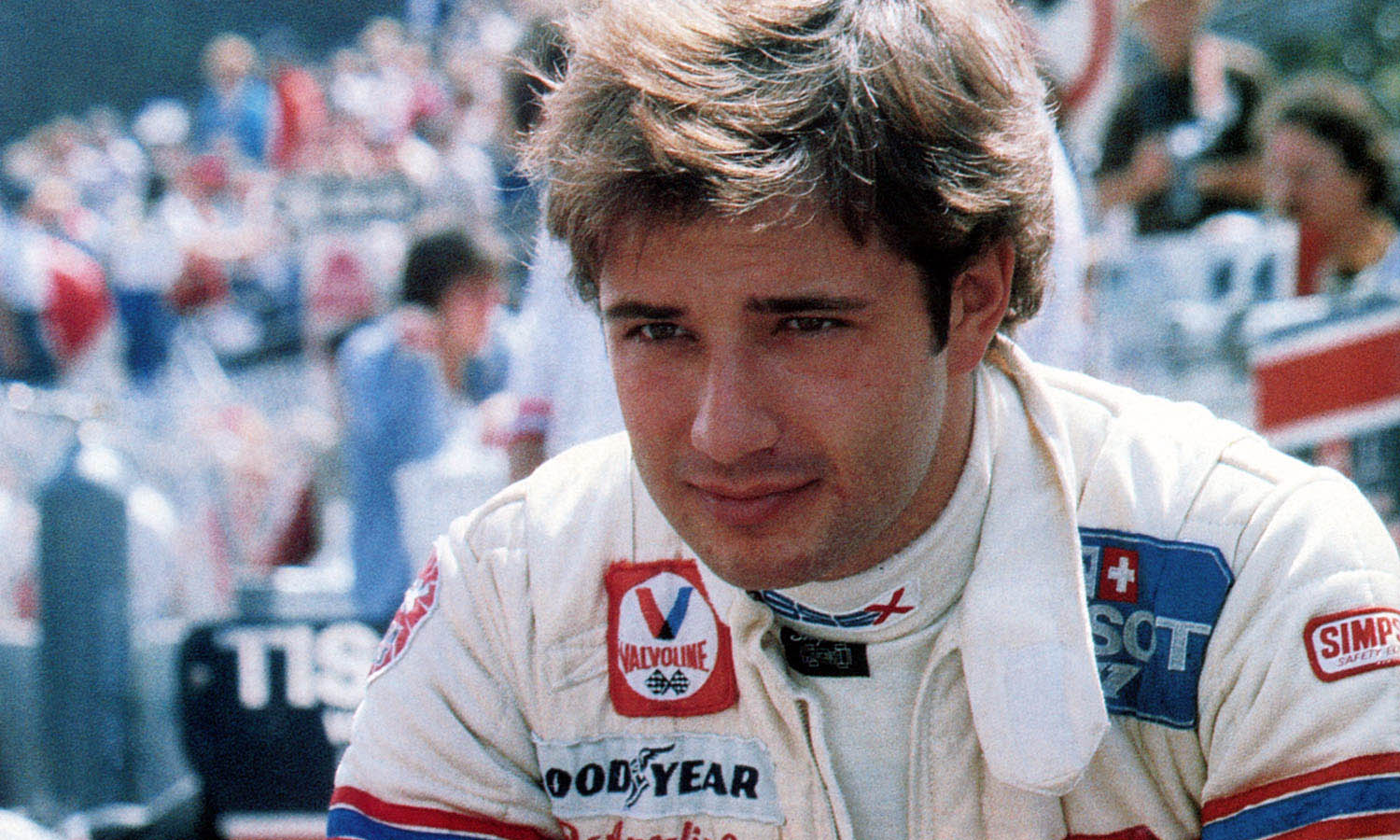

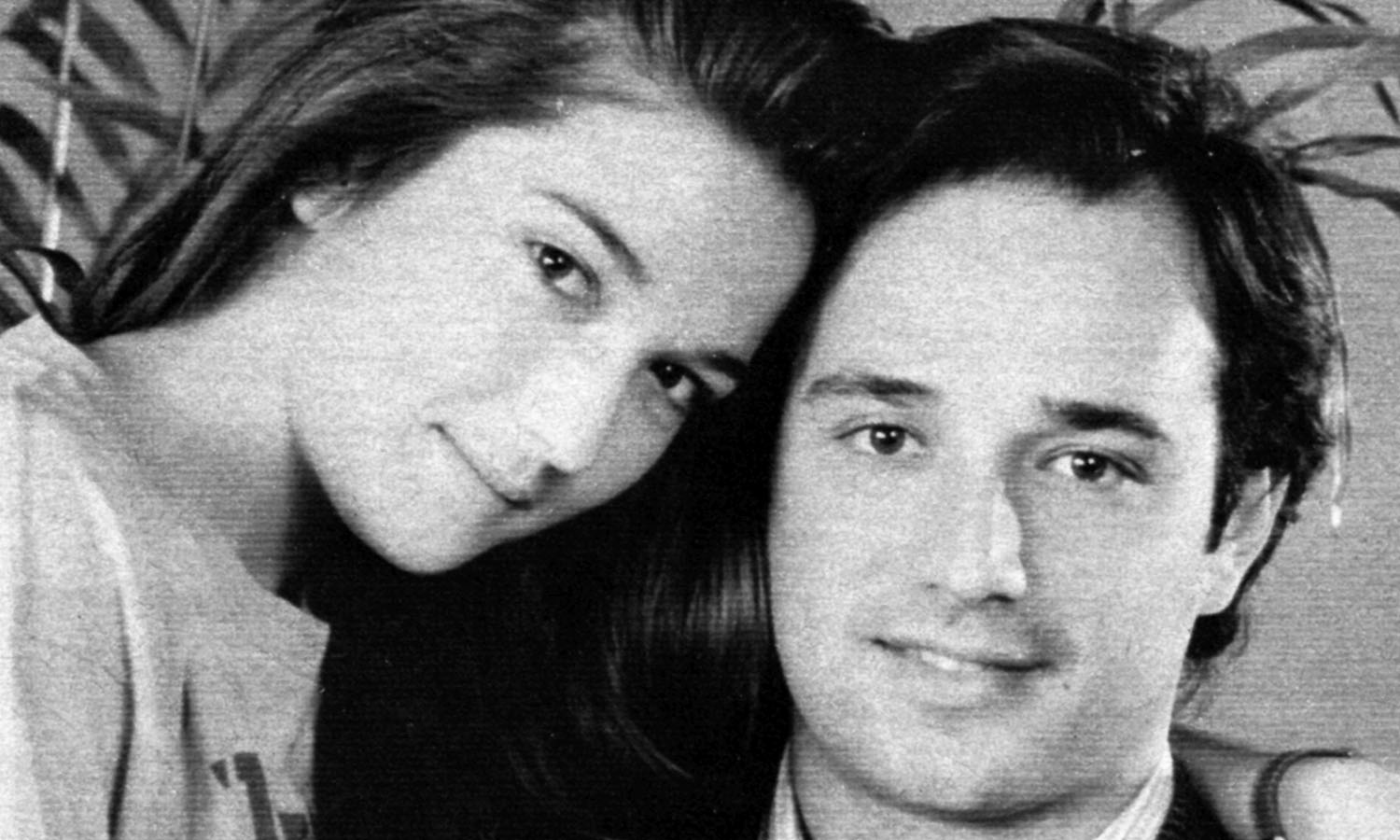

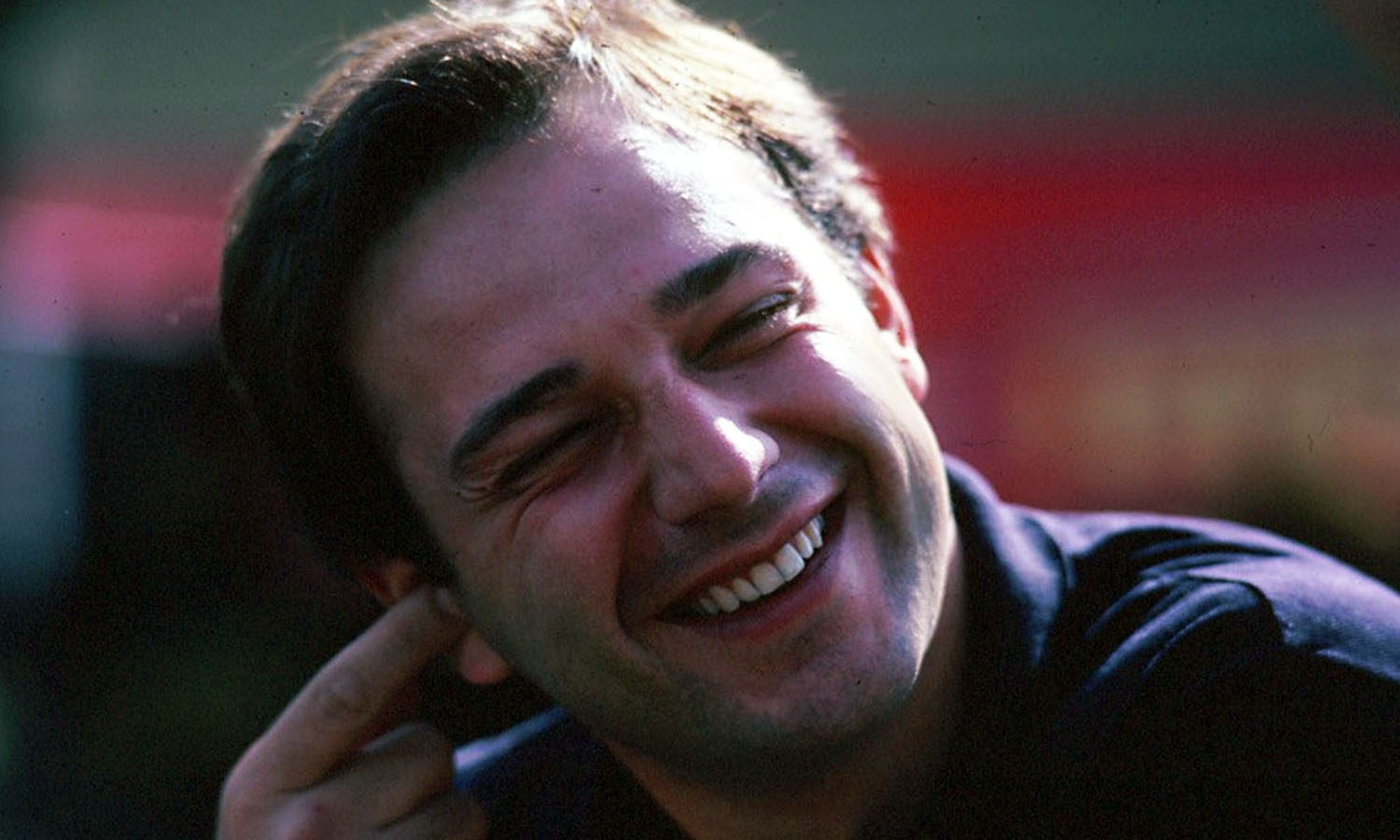

Elio was the cool one – the Roman with the Hollywood looks who played jazz piano about as well as he drove racing cars and who, through the Family construction business, had access to more Money than most F1 team owners of that time could dream about.

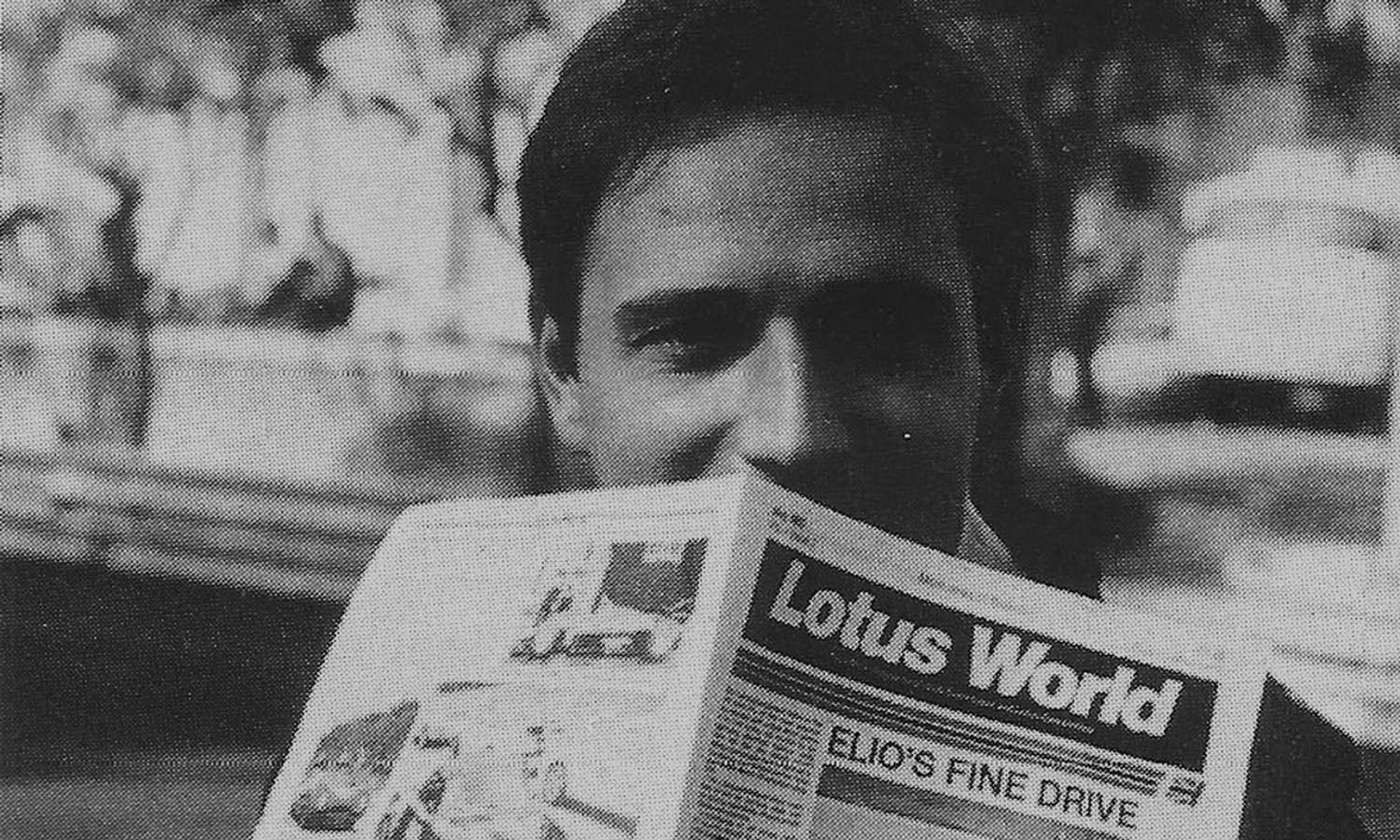

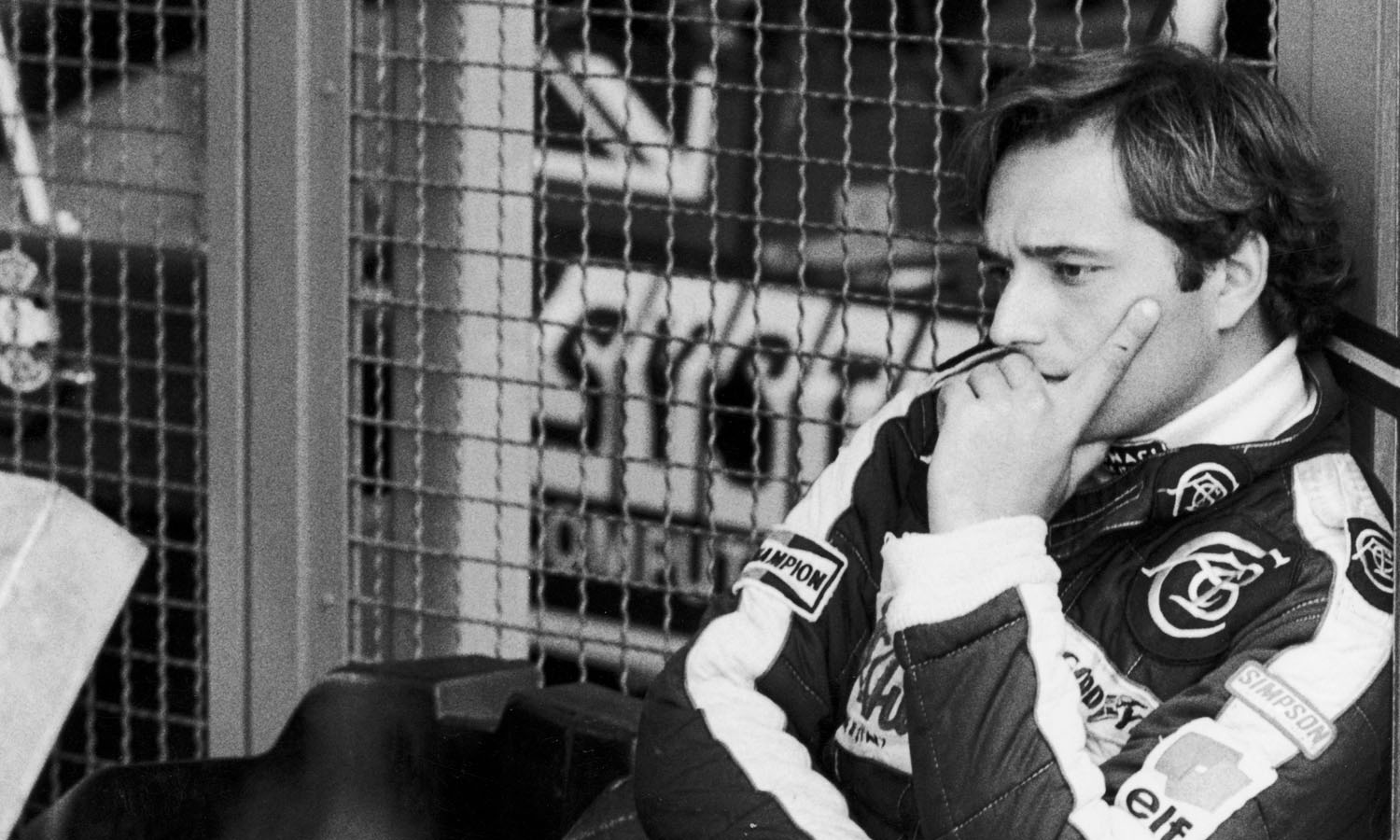

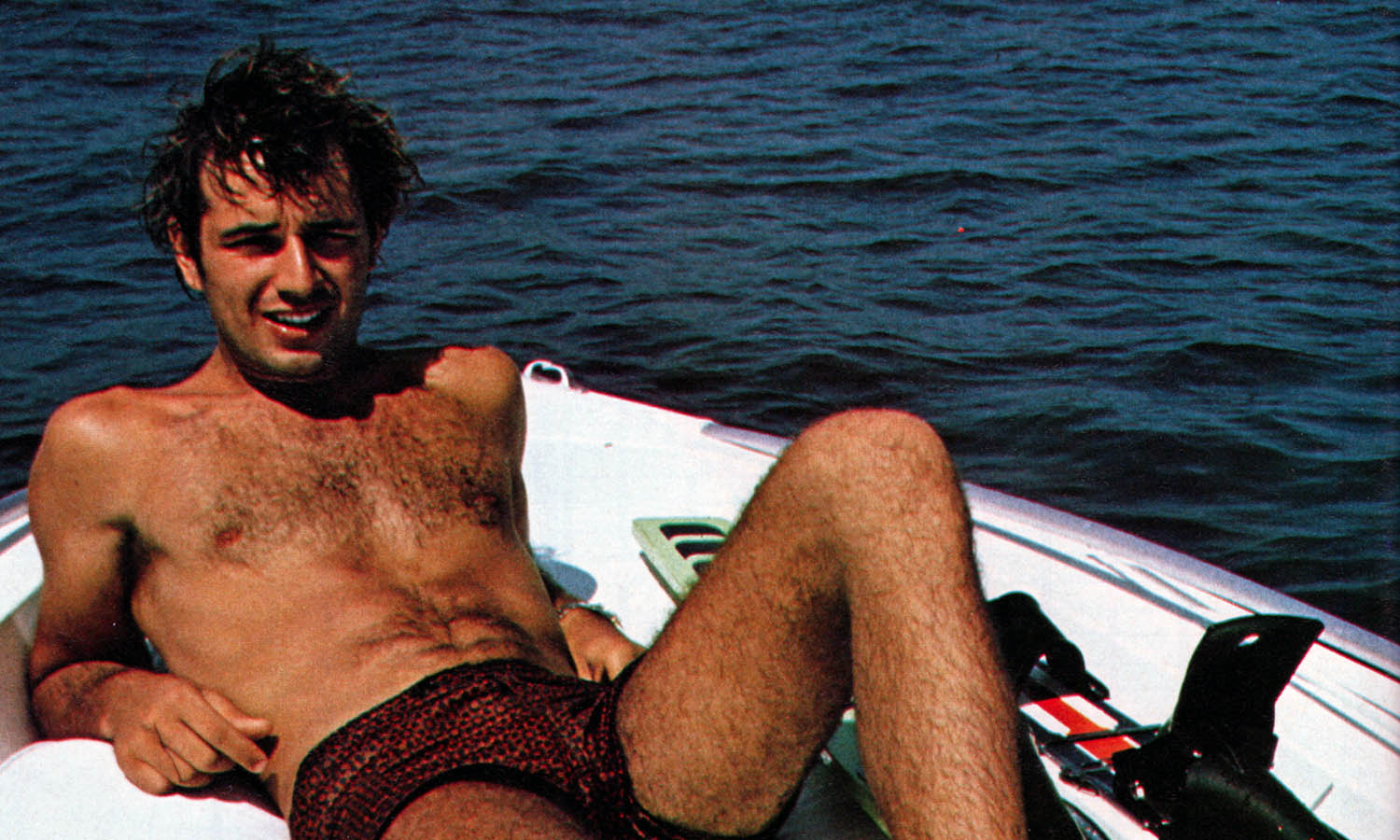

Not that you’d know that when you hung with Elio (pronounced ‘El-eo’, even though Colin Chapman Always used to call him “Eeeel-leo”). I spent a couple of days with de Angelis and the guys in Mauritius at the end of 1985. We were en route from South Africa to Australia – to the first AGP, in Adelaide. It was Early summer and Elio was at once the athlete (wind-surfing, tennis, soccer), the impeccably mannered, multi-lingual dinner host (beige, long-sleeved Hugo Boss shirt, lightly unbuttoned, faded jeans) and the improviser of wonderful music. There was nothing ostentatious about him, nothing elitist. He was just one of the guys – one of the classiest of the guys, indeed, who ever sat in a racing car.

During the day, between swims and before the afternoon tennis match, Elio would occasionally pause his latest Al Jarreau tape and talk of the year ahead, of his plans to switch from Lotus to Brabham. Elio was a mate of Nelson Piquet’s and since the early ‘80s had accepted Nelson’s Brabham success (which is to say two world championships) with a mixture of genuine respect and almost carnal desire for his car. Now, with Nelson switching from Brabham to Williams, Elio was making his move: he would fill Nelson’s seat and continue the run of wins. In Mauritius he spoke of Brabham’s famous designer – Gordon Murray – and of the new, semi-reclining driver position that would be required for the new Brabham. He spoke of his relief to be leaving Lotus. He spoke of life and how much he loved it…

Elio was the cool one who had the Hollywood looks and played Jazz piano as well as he drove cars

He never made his money obvious – especially when it came to negotiating a drive in the lower rungs. He wanted his talent to do the talking: he was too intelligent, too aware of reality, to live with anything less. He won in F3 in 1977 and quickly graduated to F2 – to Minardi-Ferrari, as it happened – and thus to the attention of Enzo Ferrari himself. Like Eddie, Elio was then invited to sign an option with Ferrari. Unlike Eddie, Elio went ahead with the deal. He was 19.

A few months later he realised that the move had been a mistake. He had tested the F1 car a couple of times, proving quick and consistente, and Elio’s supporters had pointed out that Gilles Villeneuve’s seat was by no means firm: should Gilles keep shunting, in Other words, Elio might replace him.

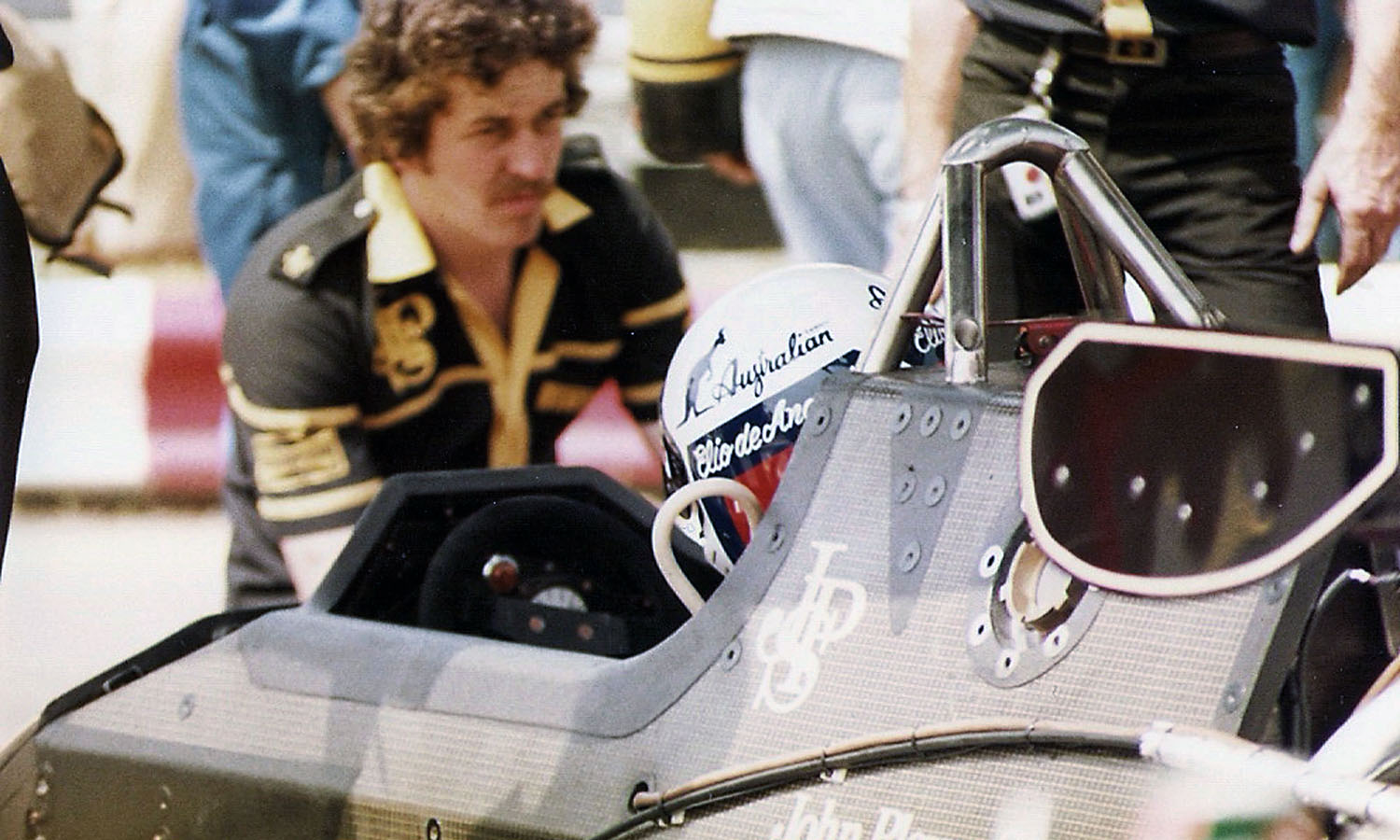

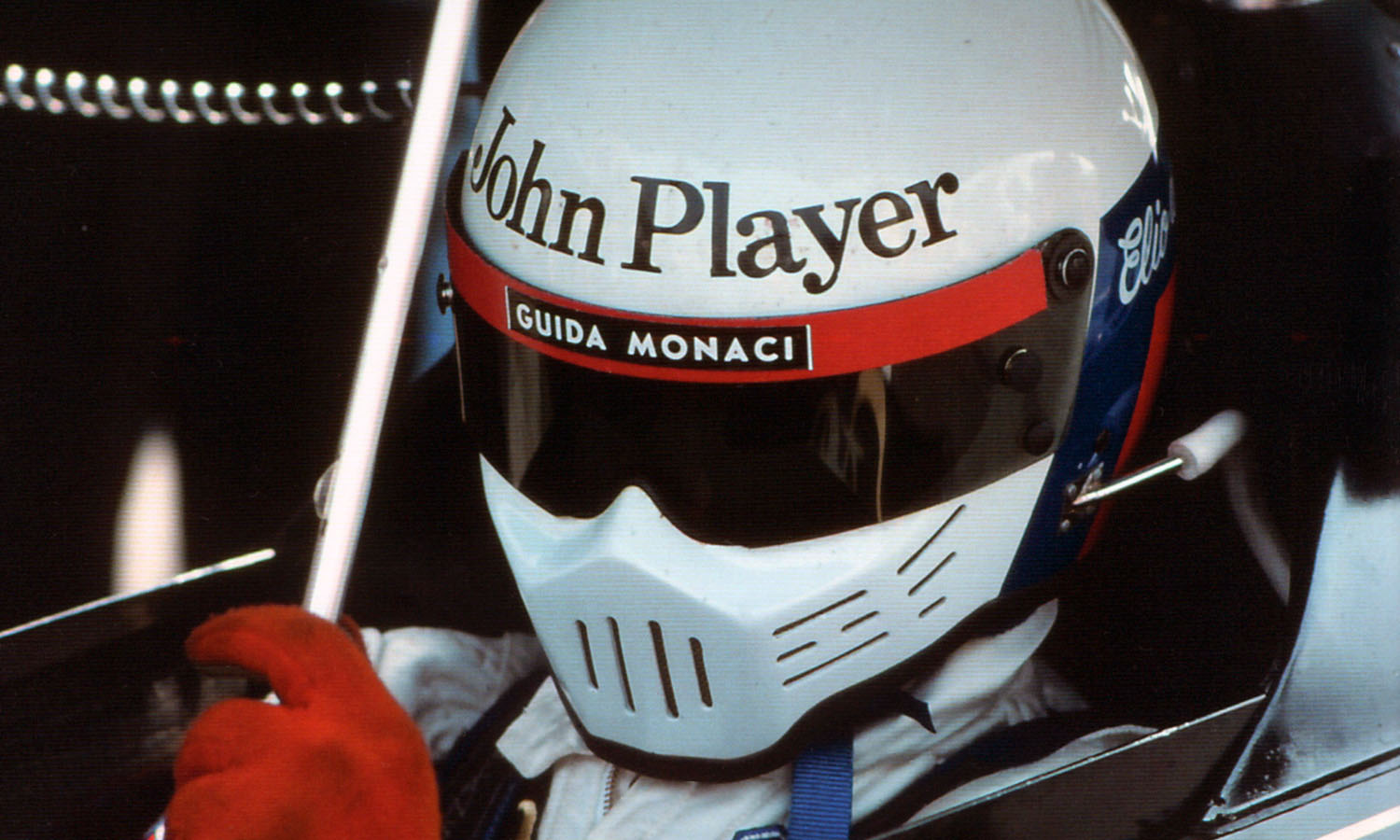

Gilles found his feet, though, and Elio, an Italian in the most political of racing countries, decided instead to adopt the British racing system. He walked away from Ferrari, bought a drive with the works March F2 team and then signed to drive F1 for Tyrrell in 1979. As the season opener approached, however, Tyrrell made other plans. Caught in a contractual maelstrom, Elio switched at the last minute to Shadow, promising a 17-race budget when in reality he had enough sponsorship (from Staroup Jeans) for only half a season; Elio borrowed the balance of the Money from his father.

He was quick and aggressive but to most F1 observers still very much the rich kid. One who felt otherwise was Peter Collins, the assistant team manager at Lotus. He persuaded Colin Chapman to hold a run-off at Paul Ricard at the end of 1979. The winner of the contest would be Mario Andretti’s team-mate in 1980.

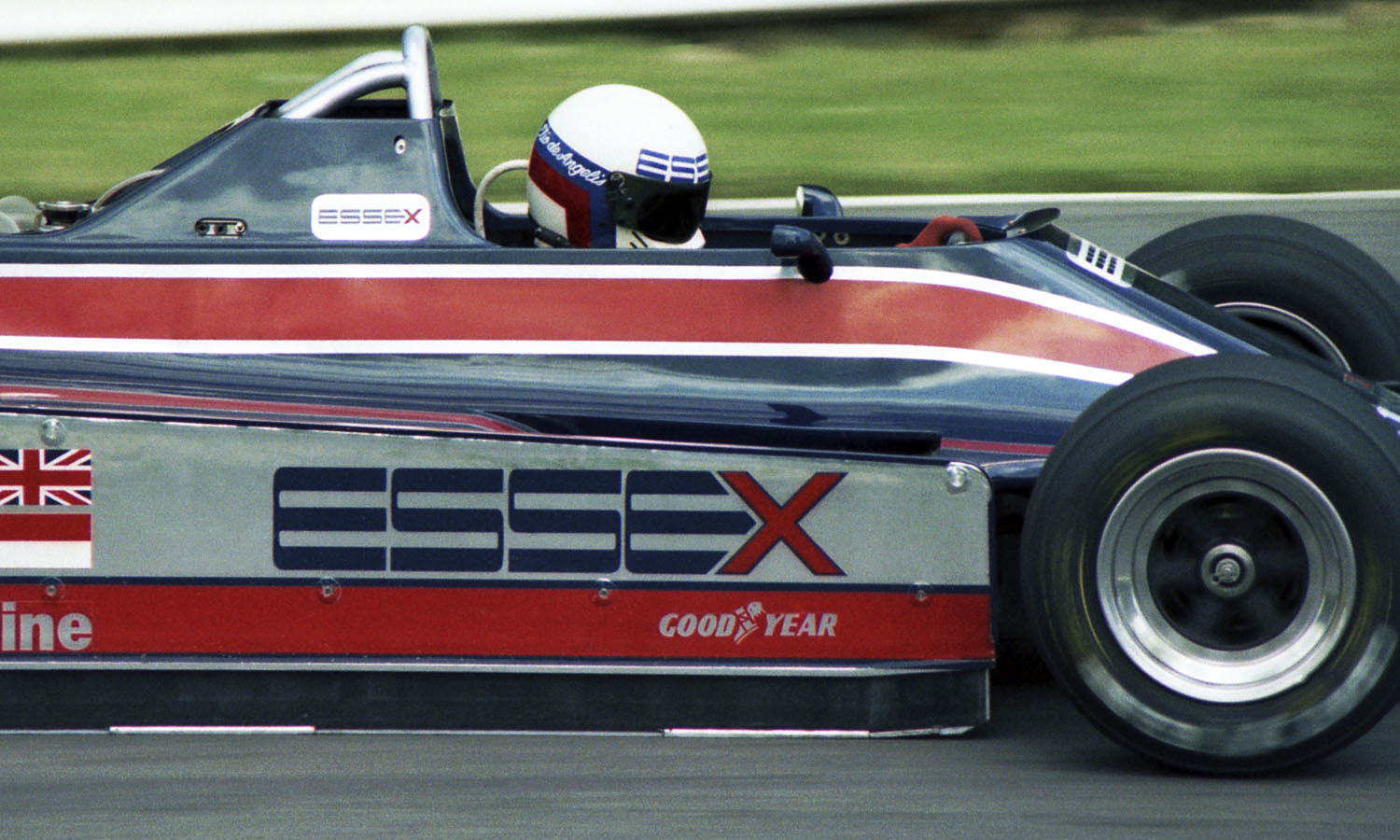

Eddie, Jan Lammers (Elio’s team-mate at Shadow), Elio and Nigel Mansell, a young F3 driver, were invited to drive, although Mansell was not considered at that point to be more than a long-term junior test prospect. The race for the position was the one that took the headlines – and Elio won it with ease. He signed to drive for Essex Team Lotus in 1980, ’81 and ’82.

He instantly showed his speed by nearly winning the Brazilian Grand Prix at Interlagos after a great drive over the bumps with the Lotus 81-Ford. A year later, by which time Elio had repaid his father and was now number one at Lotus, Mike Doodson asked him about the win that got Away at Interlagos: “Of course I was disappointed, but I did have some serious problems with the car, like a sticking skirt and badly worn tyres on the left side. But I must tell you that I am convinced, now, that if I had won that race it would have been very bad for my career”, said Elio modestly. “At that stage, I could not have afforded to be in a position where I felt I could win consistently.”

Instead, by 1981, Elio was facing a different problem – his new team-mate, Nigel Mansell. Shortly after Nigel had qualified third at Monaco, 0.4sec quicker than Elio, Eddie Cheever couldn’t resist a tease: “Thought you said Colin had hired some English rente-a-driver for the other car…”

Elio was the number one driver, Nigel the number two – but frequently raced side-by-side, absolutely on the limit. Dijon that year will Always be remembered for the closing lap, wheel-bashing battle between René Arnoux and Gilles Villeneuve. Further back, though, a lap down on the turbo cars, Elio and Nigel were racing just as fiercely.

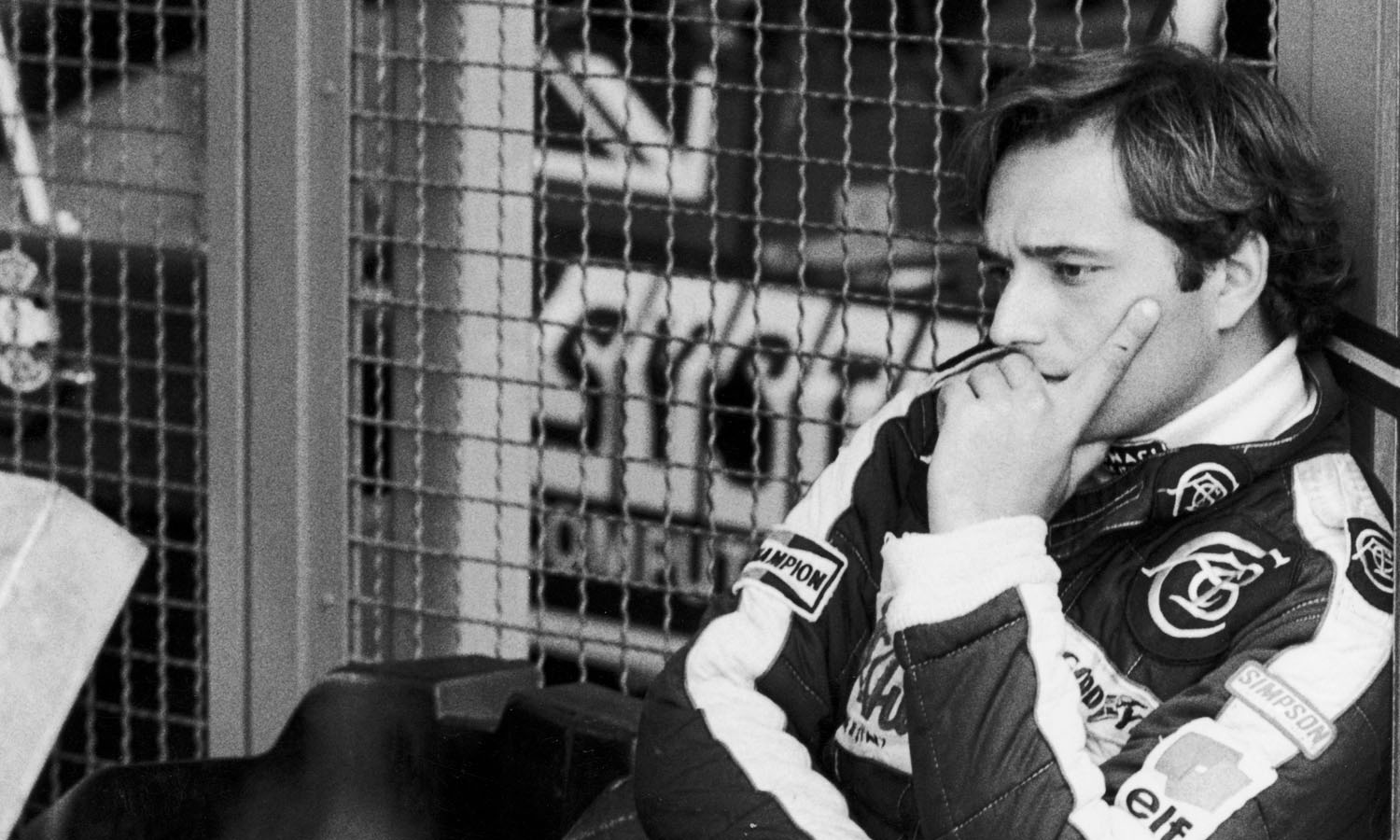

Elio won that battle – as he would win others. His stature grew in Every part of the pit lane. He was very fast, very smooth and very bright. His day would come. In mid-1982, with his Lotus contract approaching renewal, Elio was approached by Williams. He vacillated for a while, tempted by the quality of the engineering at Didcot, but was convinced that he must, above all, race with turbo power in 1983. Williams could make only vague promises of an upcoming deal (They were in preliminary talks with Honda); Lotus had a Renault turbo deal in place.

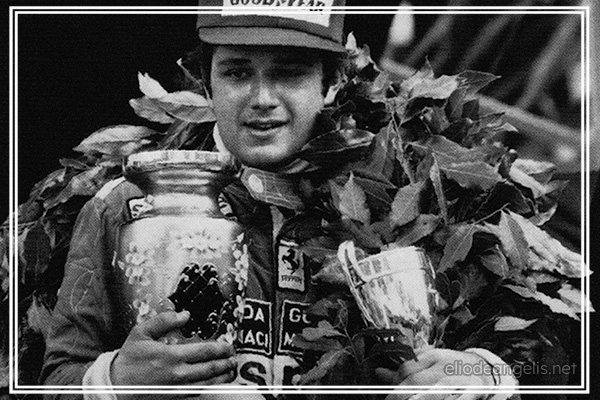

Of course, Elio should have switched to Williams. He'd have won more races there

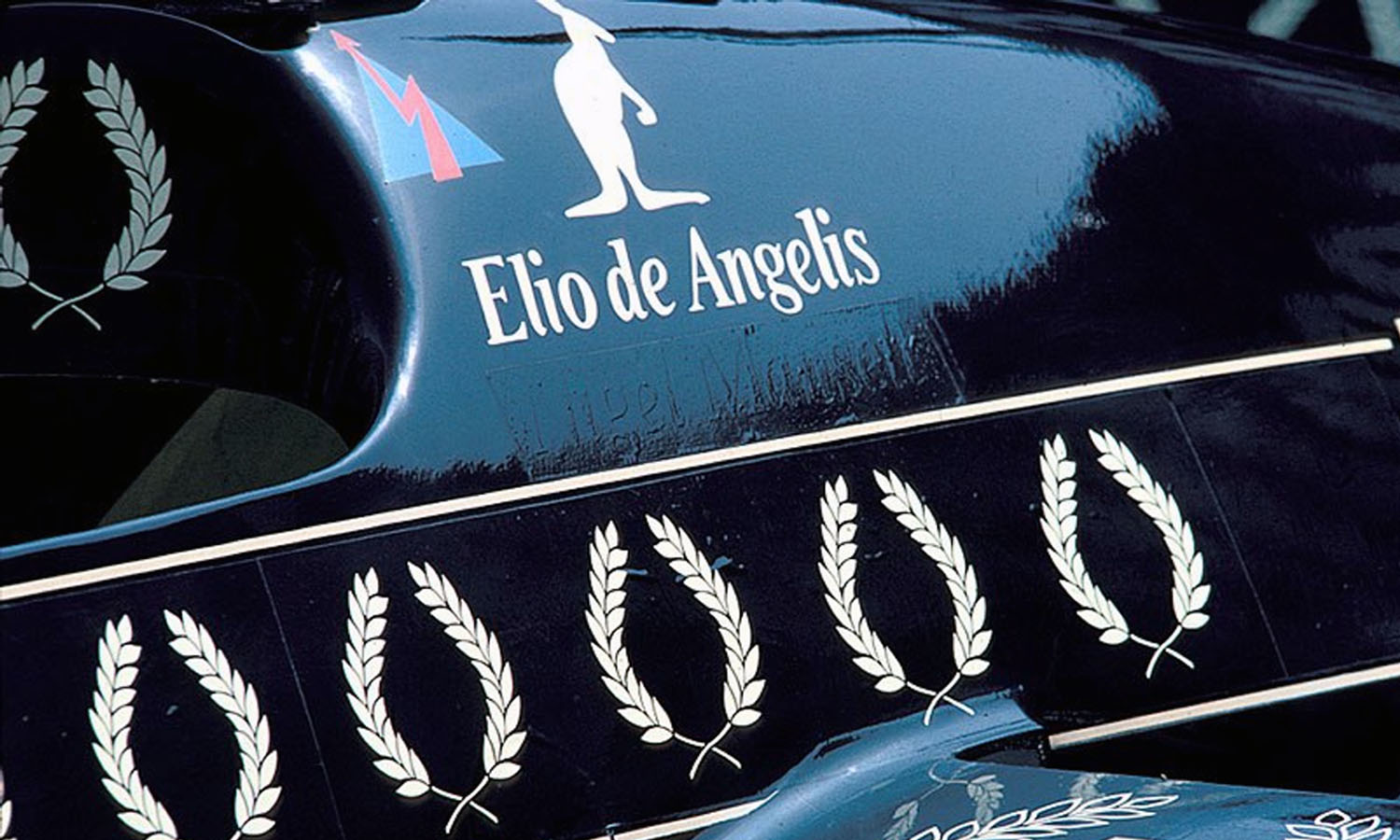

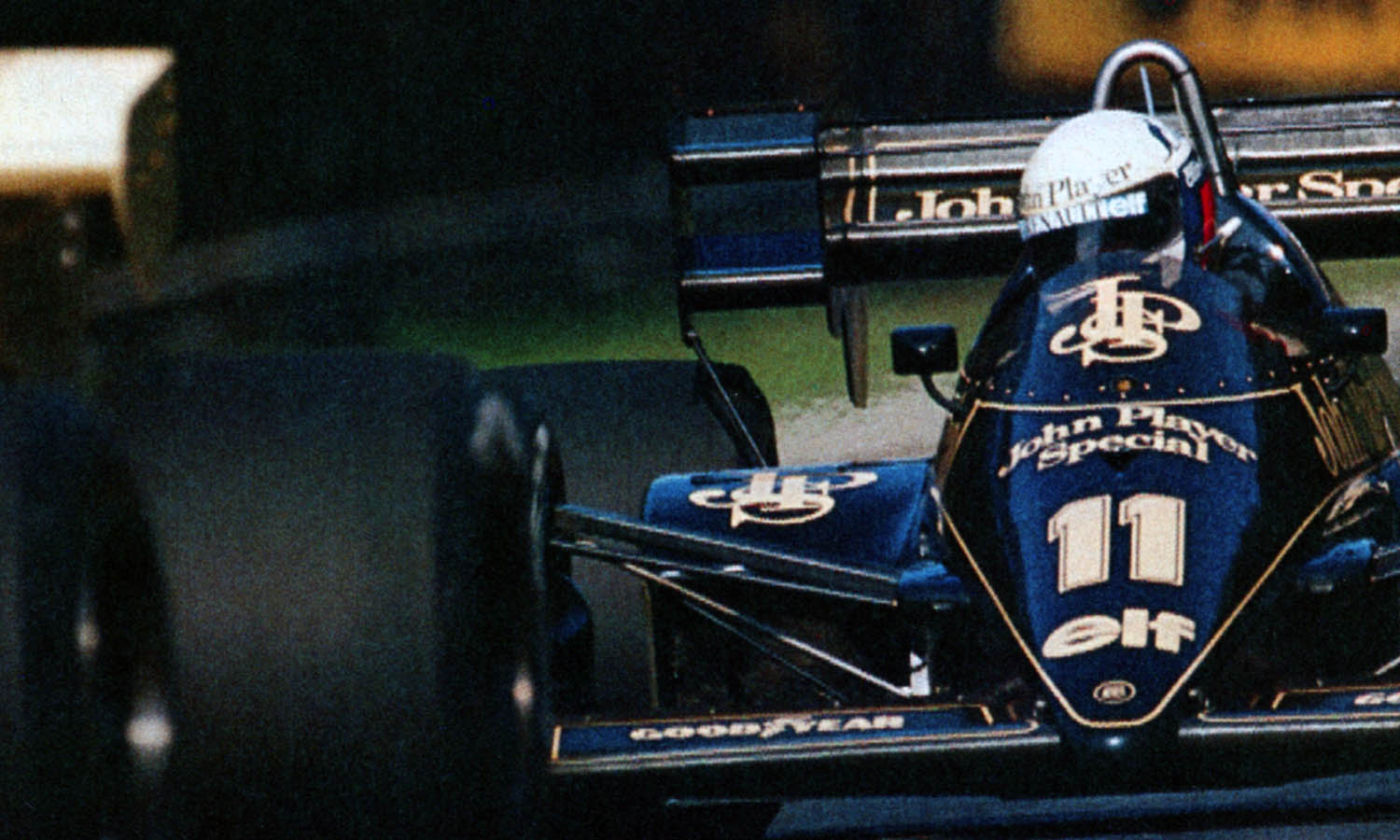

And so, on the morning of the 1982 Austrian Grand Prix, on August 15, Elio signed a new, multi-million dollar contract with Lotus for a further three Years. That afternoon, inheriting the lead five laps from the finish, when the injection pump failed on Alain Prost’s Renault, Elio won his first Grand Prix. Keke Rosberg, whom Elio had passed at the start, closed dramatically on the last lap. Keke was flying in his Williams; Elio’s engine was beginning to cough, short of fuel.

“I feinted him on the Bosch Kurve”, said Keke afterwards, “but he read me perfectly and shut me down”. Elio’s winning margin was the second-closest in history – 0.05sec.

Of course, Elio should have switched to Williams. He would have won more races there – would have raced again with Nigel Mansell. Instead, he trod water at Lotus and exposed himself to Ayrton Senna. He finished third in the 1984 championship behind the unbeatable McLaren-TAG Porsches and he was declared a rule-book, statistical winner of the 1985 San Marino Grand Prix.

Elio drove well that day, finishing with no brakes, but the podium ceremony was Prost’s – he was later disqualified for being under the minimum weight – not Elio’s.

Ayrton, meanwhile, scored eight poles and two wins for Lotus in 1985 but knew he would need number one status if he was to make the graph steeper in 1986. Elio had no choice but to leave.

Thus it was that he relaxed in Mauritius. He could take up Brabham where Nelson had left off.

Except that the new car was a disaster. After four bad races at the start of the year, Elio was testing it at Ricard on May 15. He hated testing in general and he hated to test this one in particular. Something appeared to fail on the rear wing as he approached the high-speed esses after the pits. The car slewed sideways and cartwheeled over a barrier. It came to rest upside down and immediately burst into flames. Elio was trapped inside. Other drivers who had stopped to help – including Nigel Mansell – could do nothing.

His funeral was held on a Golden day in Rome. I remember it as a celebration of his life as much as a sign of his passing.

The music was exquisite and up in the roof of the church flew a flock of doves, free and easy.

Later that day I walked across to the Foro Italica to watch an opening round of the Italian Open. It was close, sweat-soaked, clay-court tennis. They struggled and fought and occasionally stopped for air but finally, at the net, battle over, shadows long, they smiled and exchanged embraces and waved to the still-dense crowds.

Elio’s spirit was in the air – just as it is whenever sport turns to class, and dignity wins a battle against excessive pride or ego.

© 2011 F1 Racing Magazine • By Peter Windsor • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended