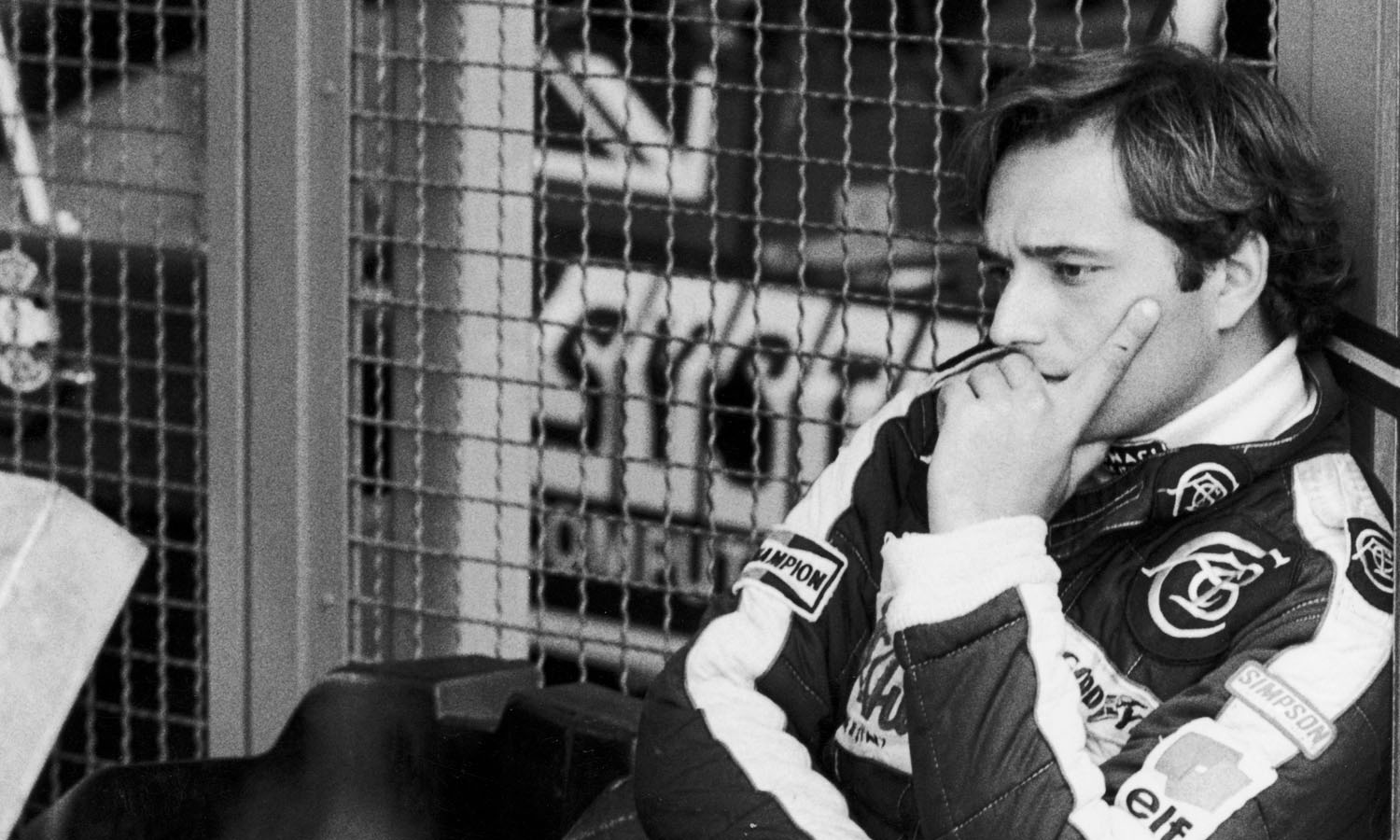

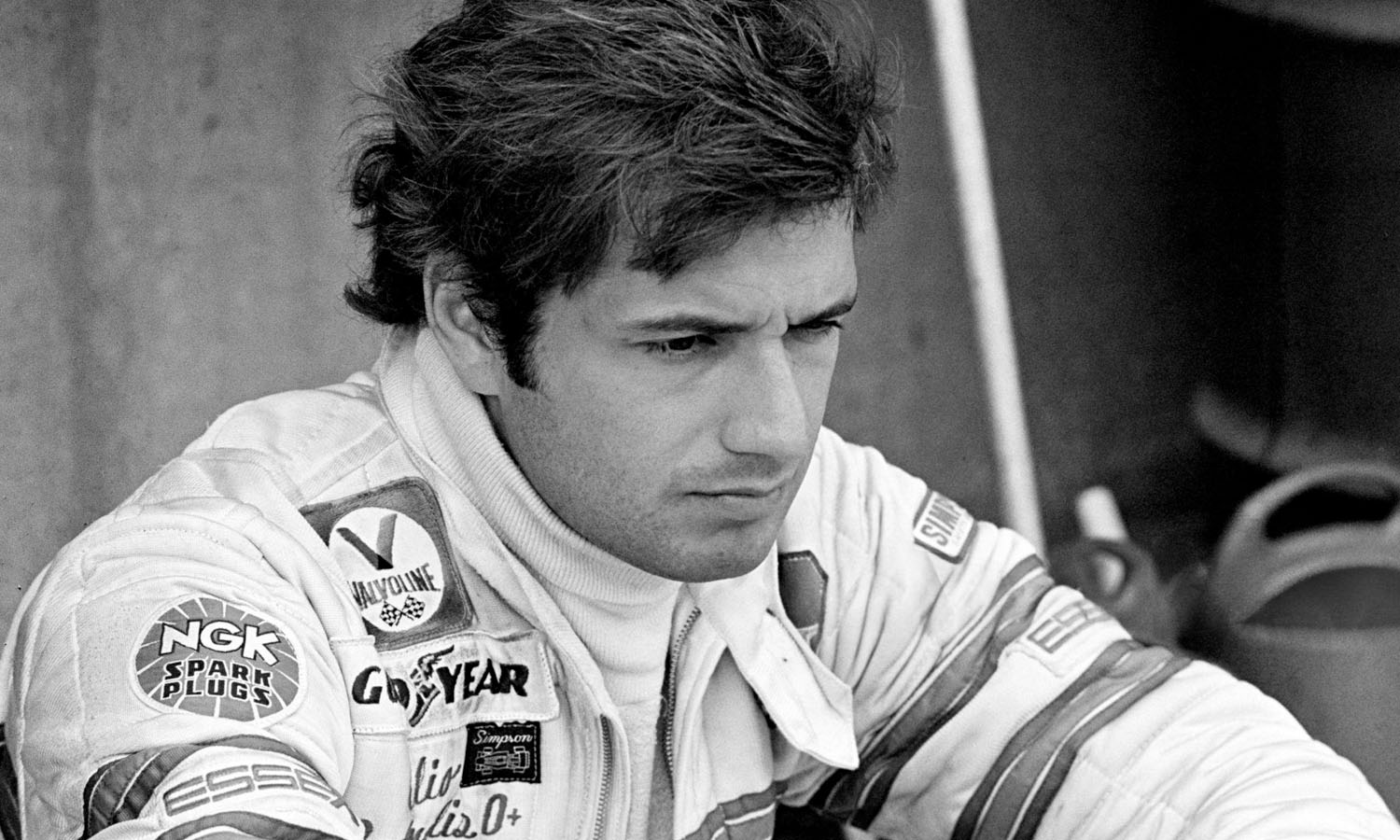

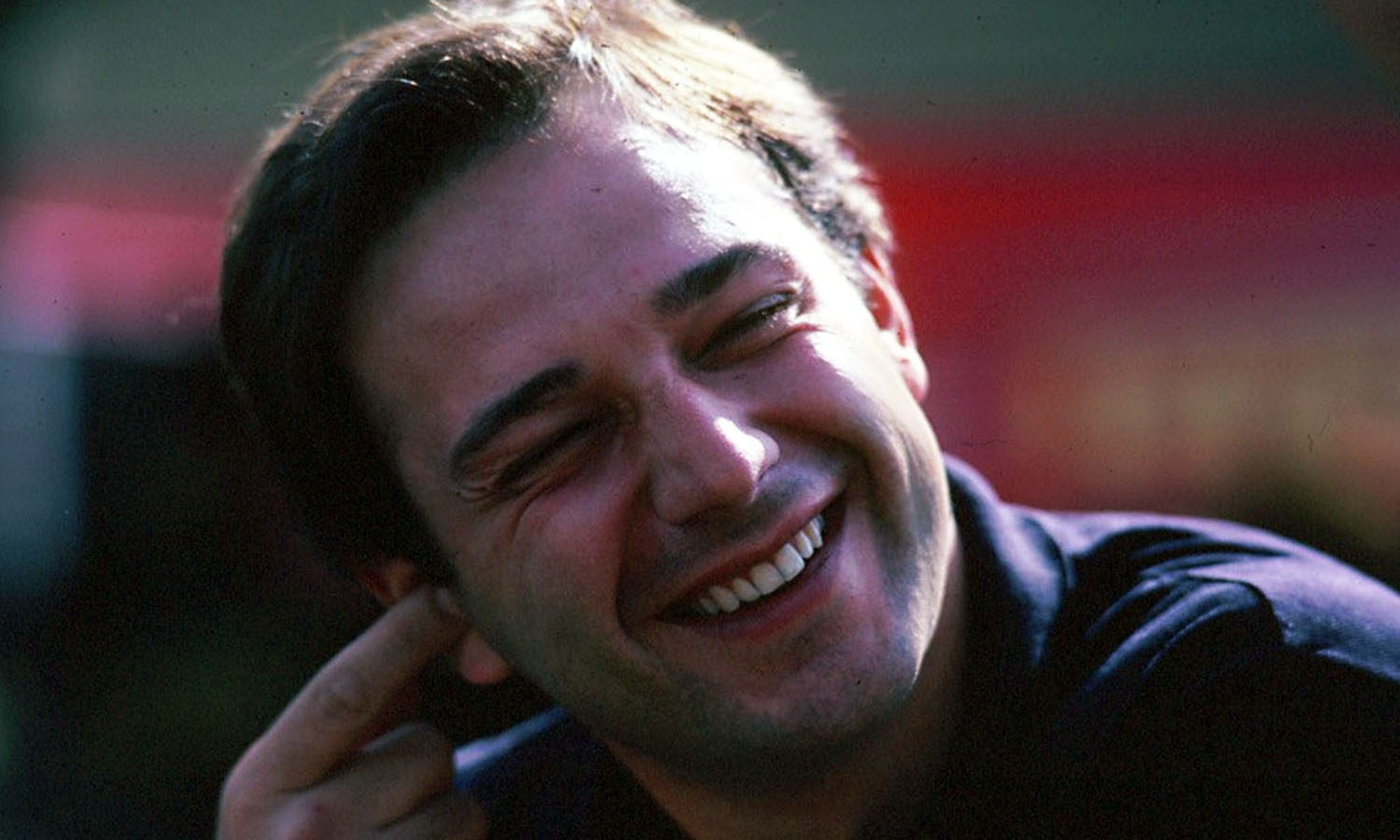

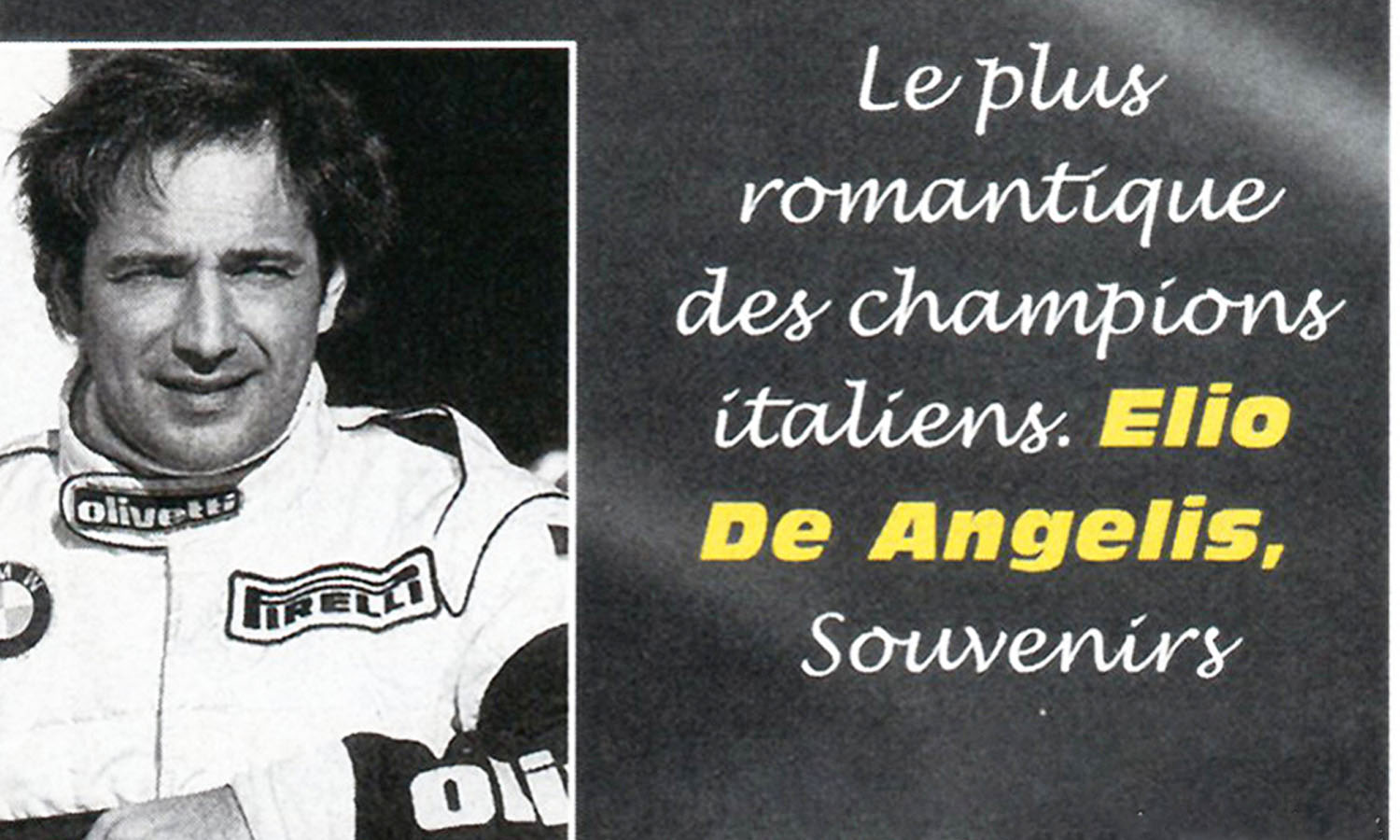

He looks like a tennis player. He’s shown many times that he has the skill and the inclination to win Grands Prix. For goodness’ sake, he’s also an accomplished pianist who adores the work of Stevie Wonder. But at 24, Elio de Angelis is still without a GP victory. Money helped him to where he is, and money will take him further. But the money which is important to him has nothing to do with the millions that stand to the credit of his wealthy father. What drives Elio de Angelis is his own worth in a high-priced profession.

Who doesn’t want to be wealthy and good-looking? For the 99.9 per cent of the world’s population who still never aspire to either of these advantages, it must be difficult to imagine that there are handicaps to wealth and good looks. There are for example, the temptations which finally got to Gatsby, the road that leads through bonhomie to overindulgence and an early grave.

On the intellectual plane, wealth can be a positive barrier. How many masterpieces were painted in a seaside penthouse? How many great works of literature flowed from the pen of a millionaire? Talent is rarely suppressed by indigence: more often than not, poverty is the spur that leads to an artist’s fame.

Today, there are practical and political drawbacks to individual wealth. If your inherited cash hasn’t been pilfered legally by a so-called enlightened government, there’s a good chance that private enterprise will be chasing it in yet more devious (and unpleasant) ways. So it is that when Elio de Angelis steps off a plane to visit his family in Rome, waiting for him will be a couple of personal armed bodyguards and a bulletproof limousine.

If he wants to stop on his way to the family villa for a takeaway pizza, the two gentlemen with the padded armpits will accompany him. The young master is on the hit list of the fled Brigades, and it is their job to ensure that he isn’t summarily disposed of by those who resent his place at the top of the social tree.

Driving racing cars, of course, is regarded as a rich man’s game, etched with enough glamour to get it social recognition, effects enough to classify it with yachting and tiger-shooting as a sport worthy of a millionaire’s time.

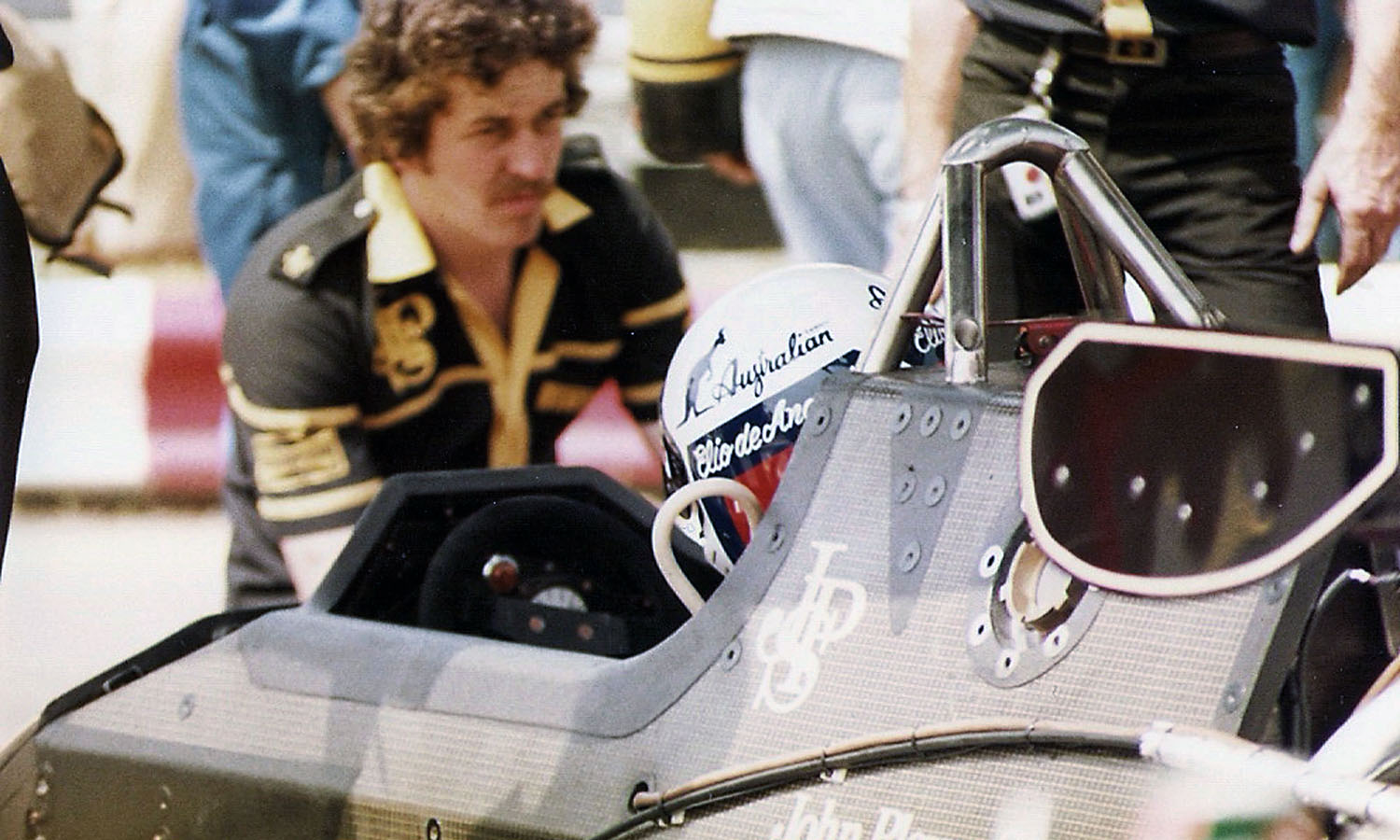

But times have changed in racing. Alfonso de Portago, the Spanish gentleman racer, mixed the Grand National with Grand Prix and got away with it, at least until he became the Mille Miglia’s most spectacular casualty. In his day there was no prequalifying, and anyway you could buy your way into a decent car, to respectable results. Times have changed, as “Fon’s” countryman de Villota may have just discovered to the cost of the family bank and some Madrileño sponsors. At 20, Elio had brought his way into Grand Prix racing. A first accommodation with Tyrrell was frustrated when Tyrrell changed his mind about the contract they’d signed (he had time to repent after a High Court judge decided in Elio’s favor), and it wasn’t much more than a year later before times had changed altogether. By then it was Elio’s own team, Shadow, which was suing him. He’d walked out on his three-year contract after one season (and promptly found himself back in the High Court, this time on the losing — but not necessarily the repenting — side).

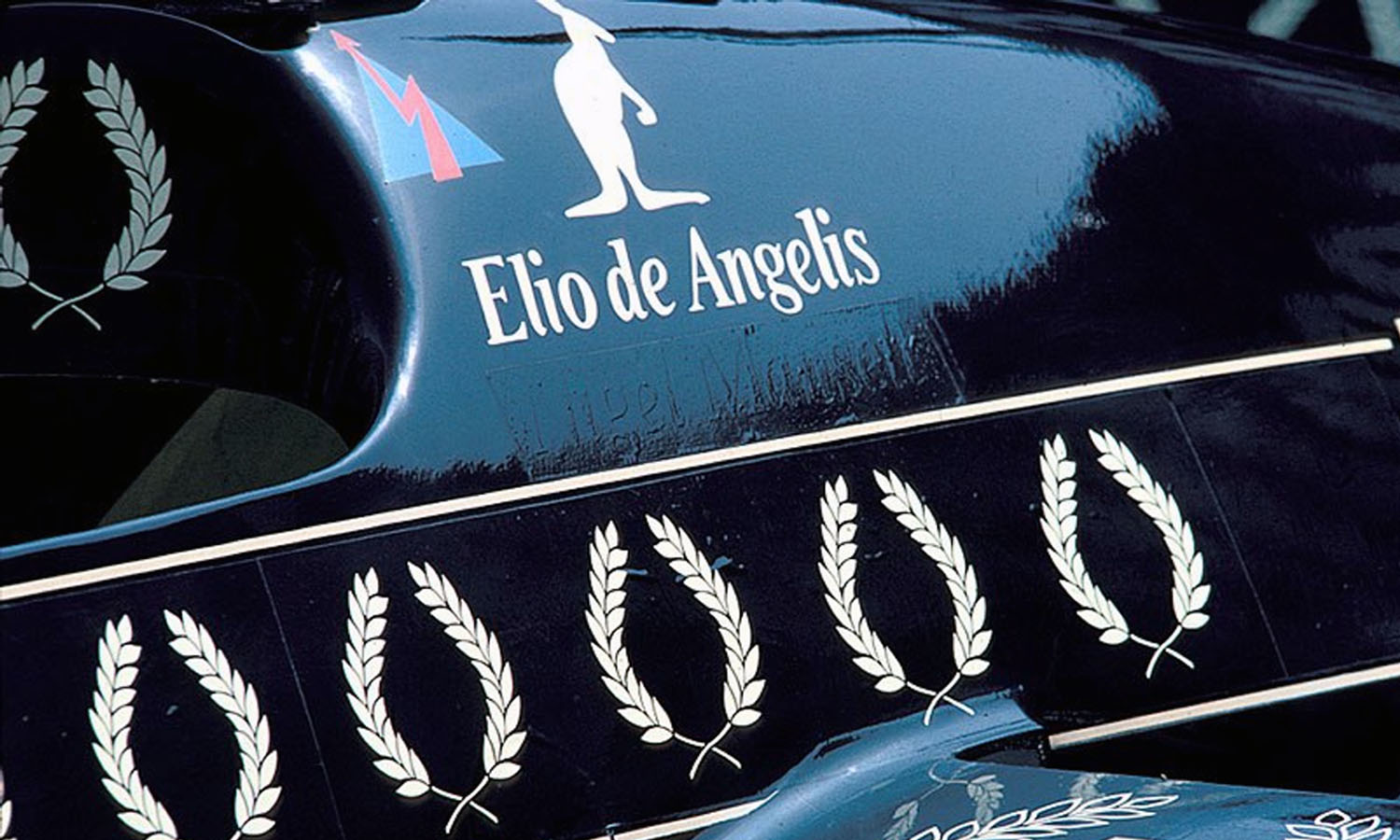

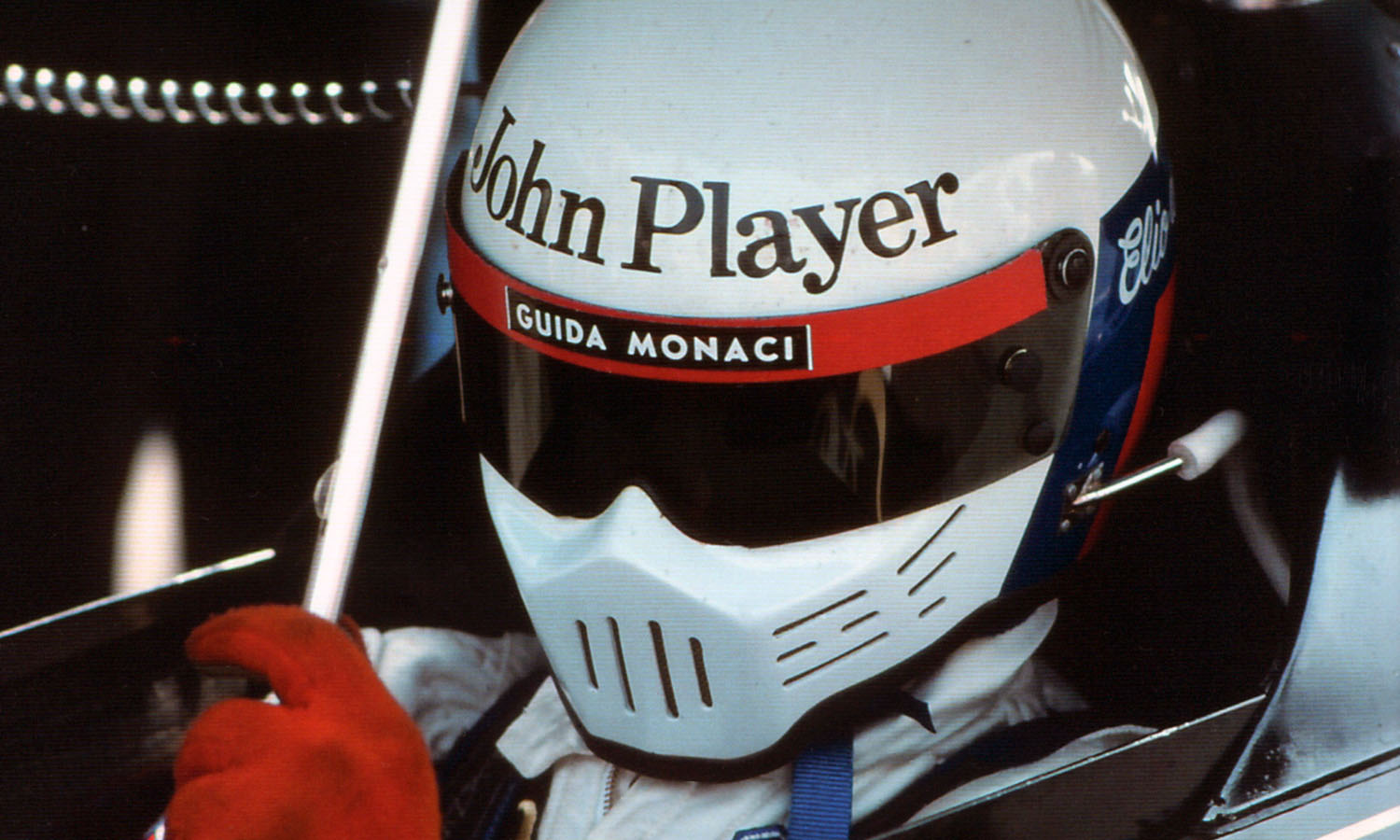

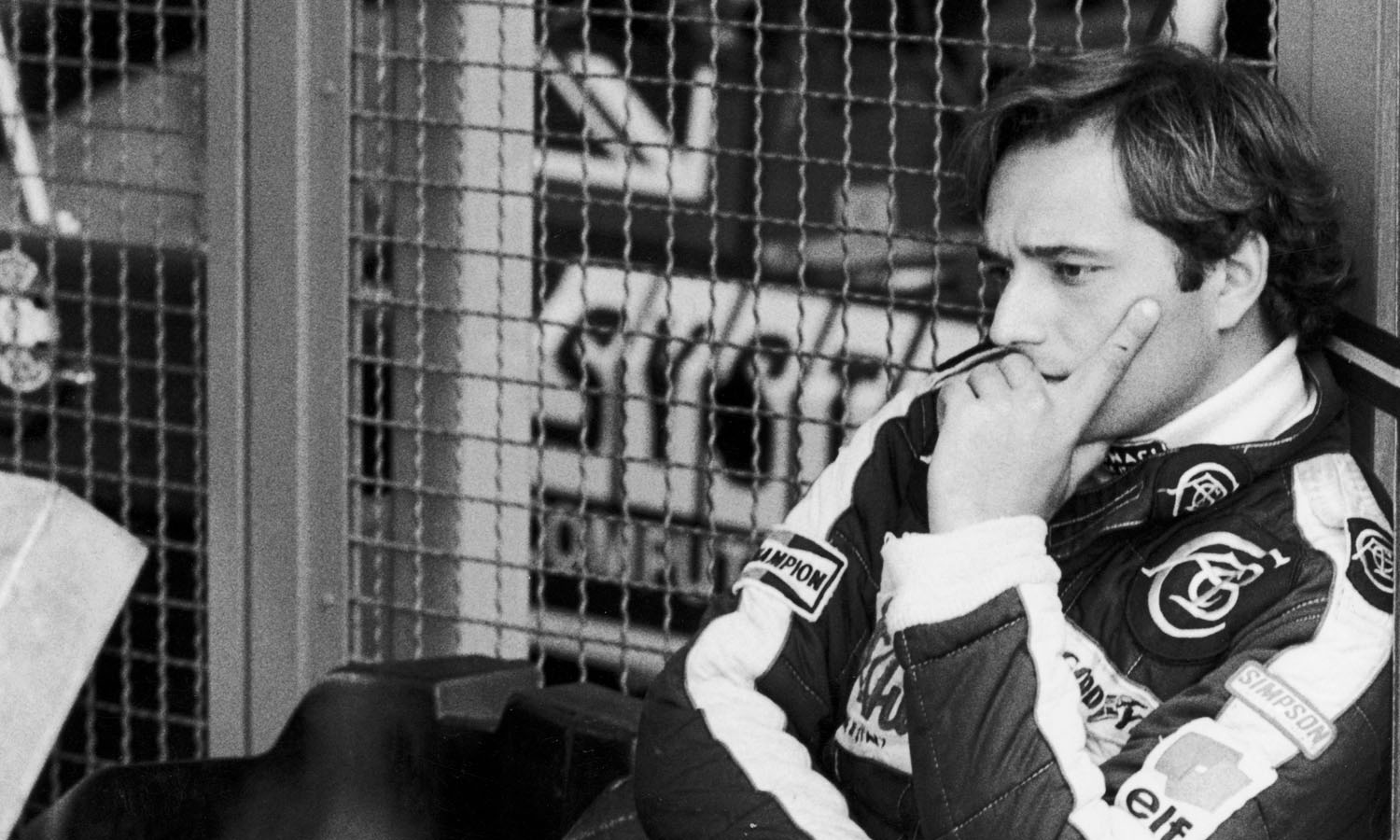

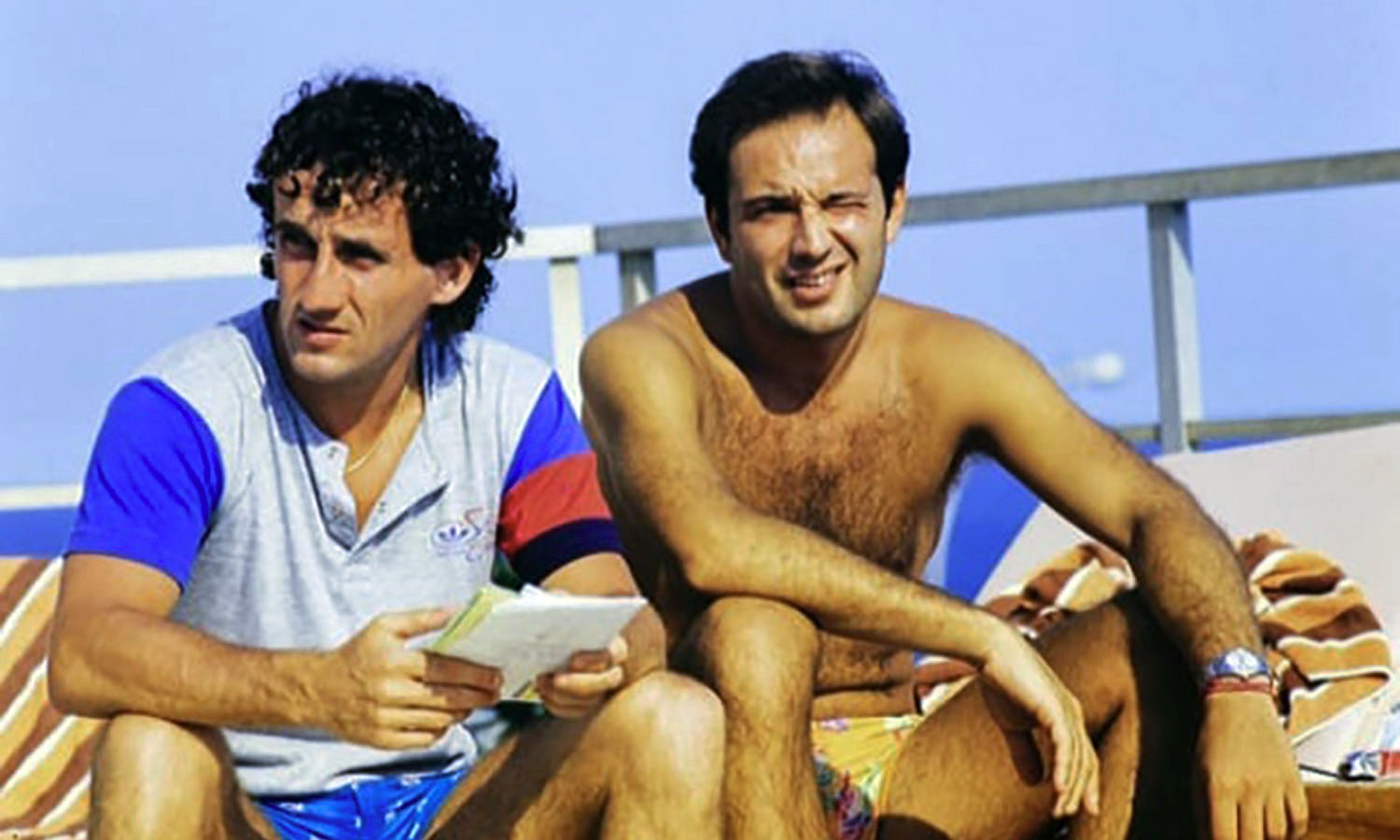

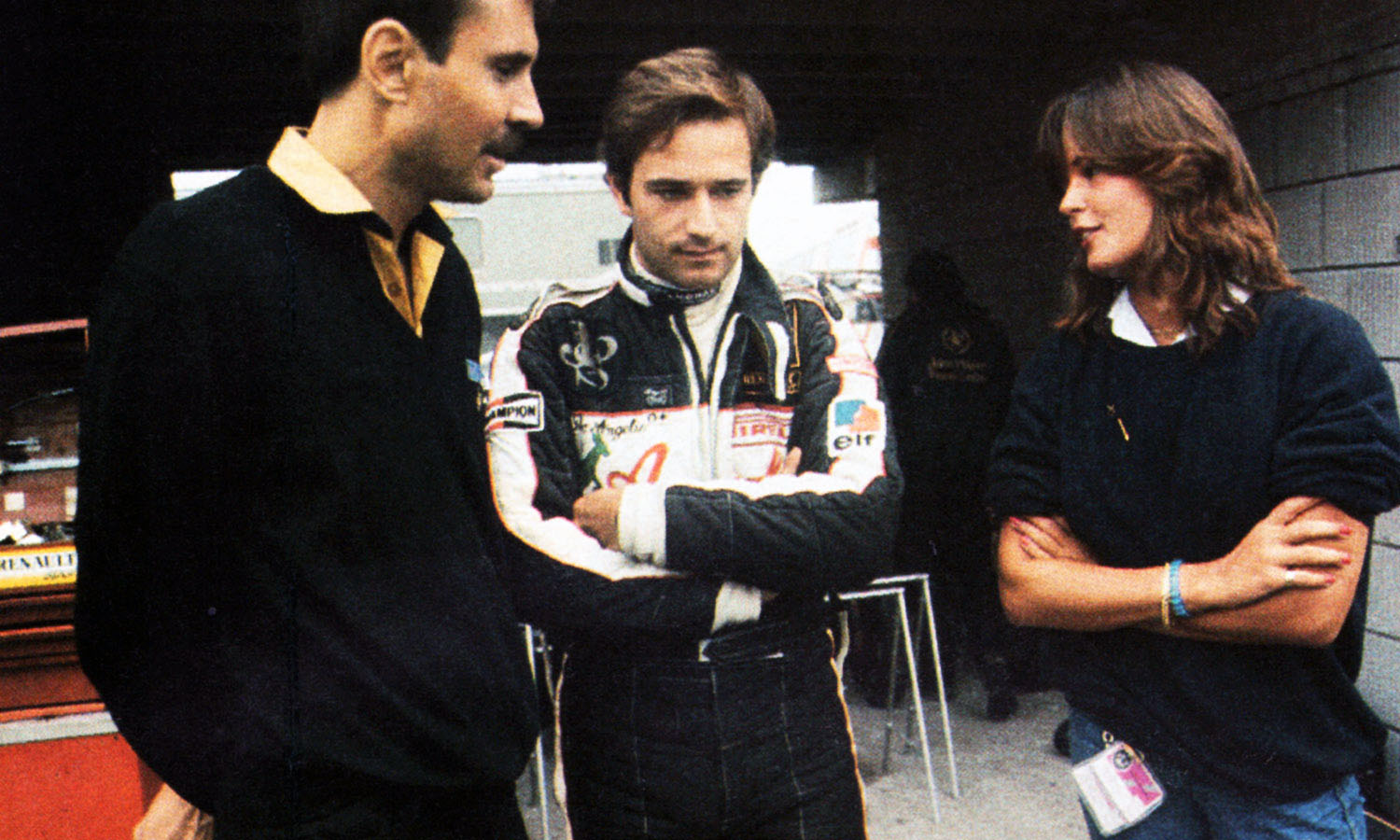

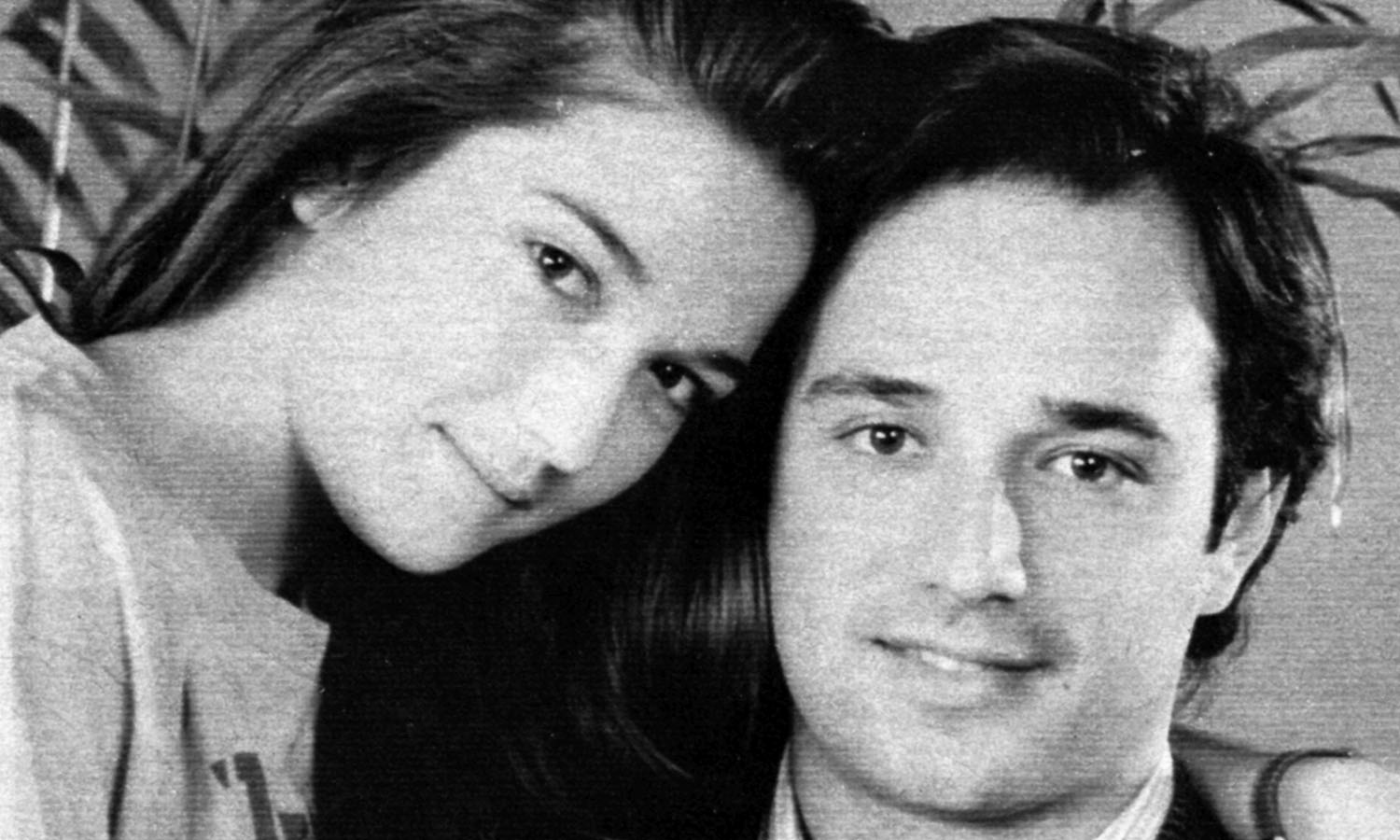

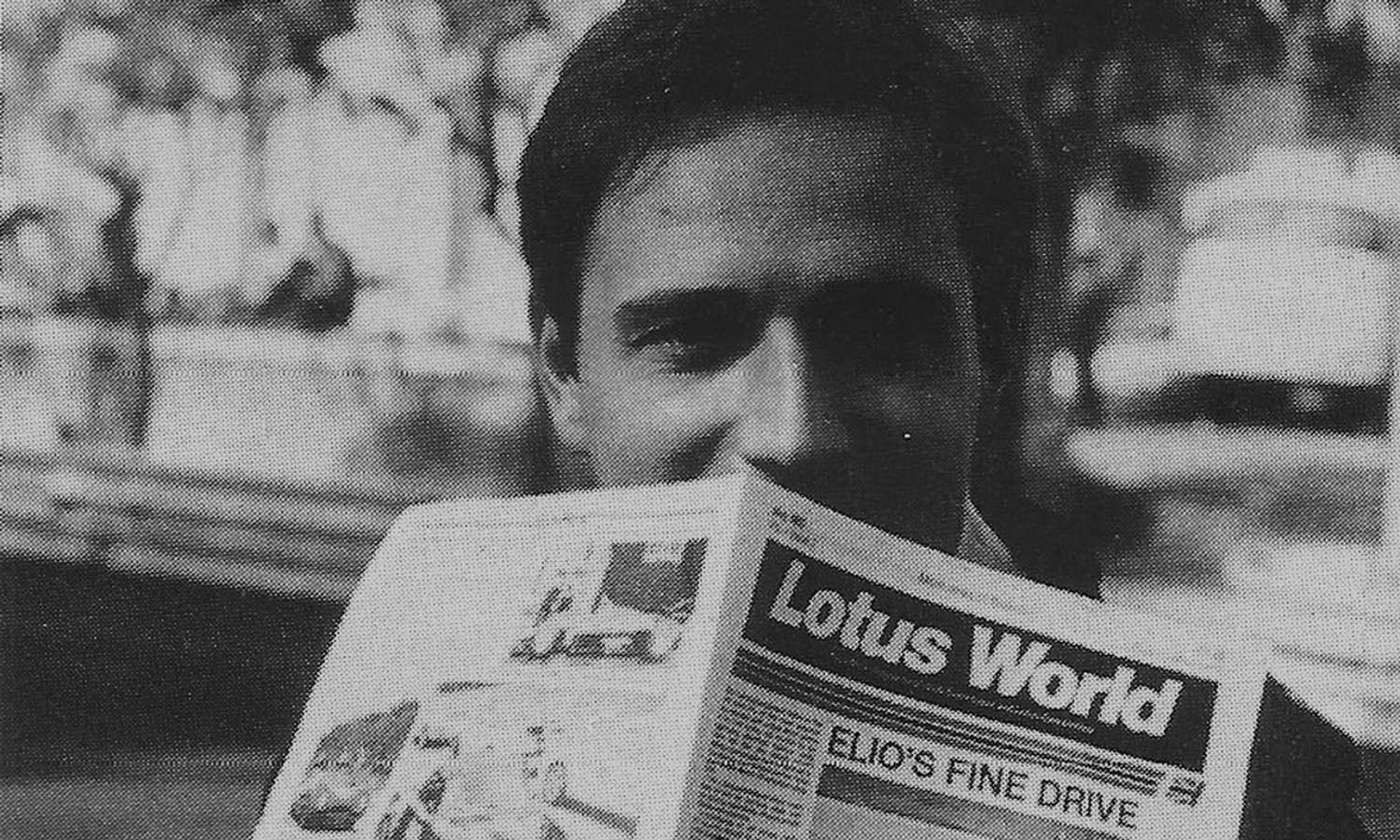

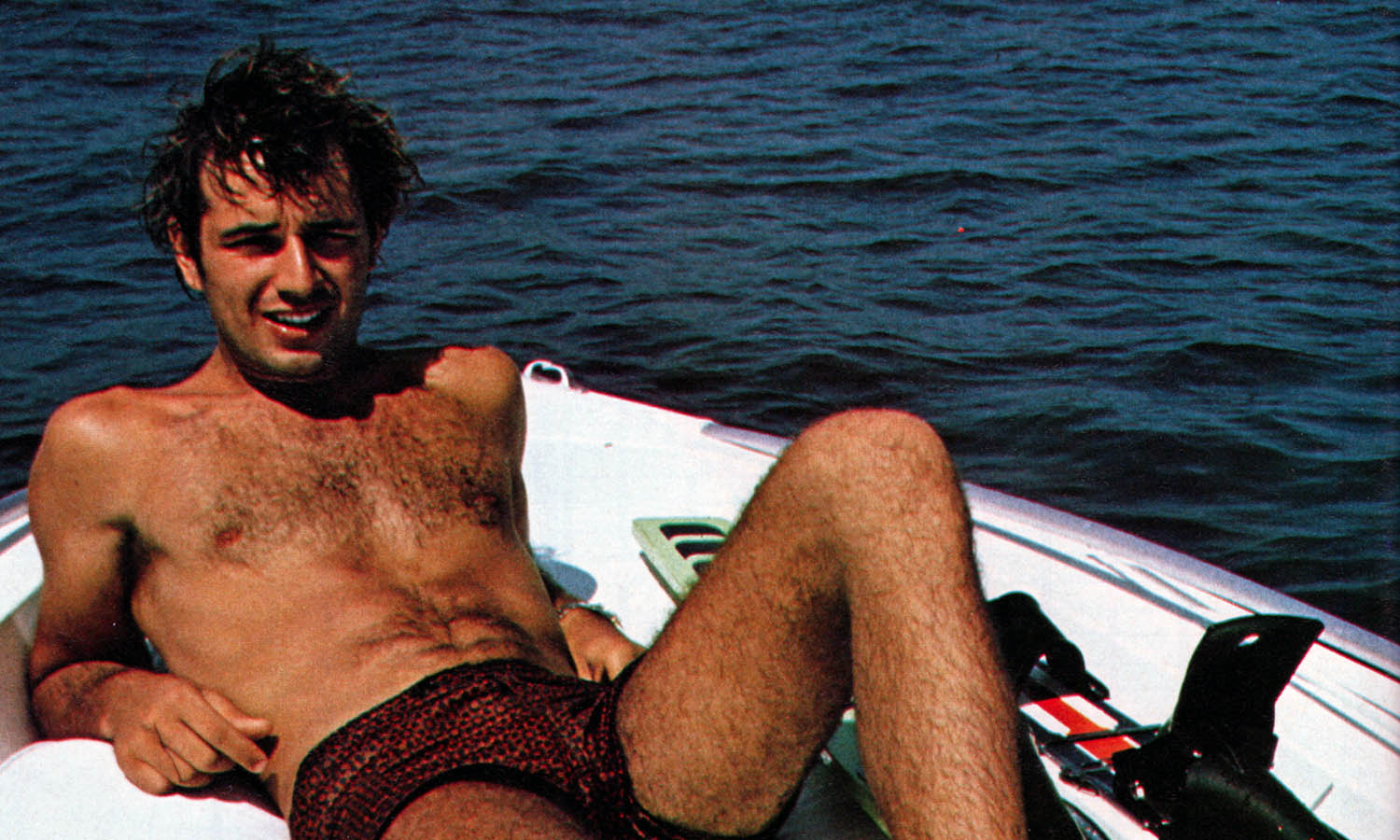

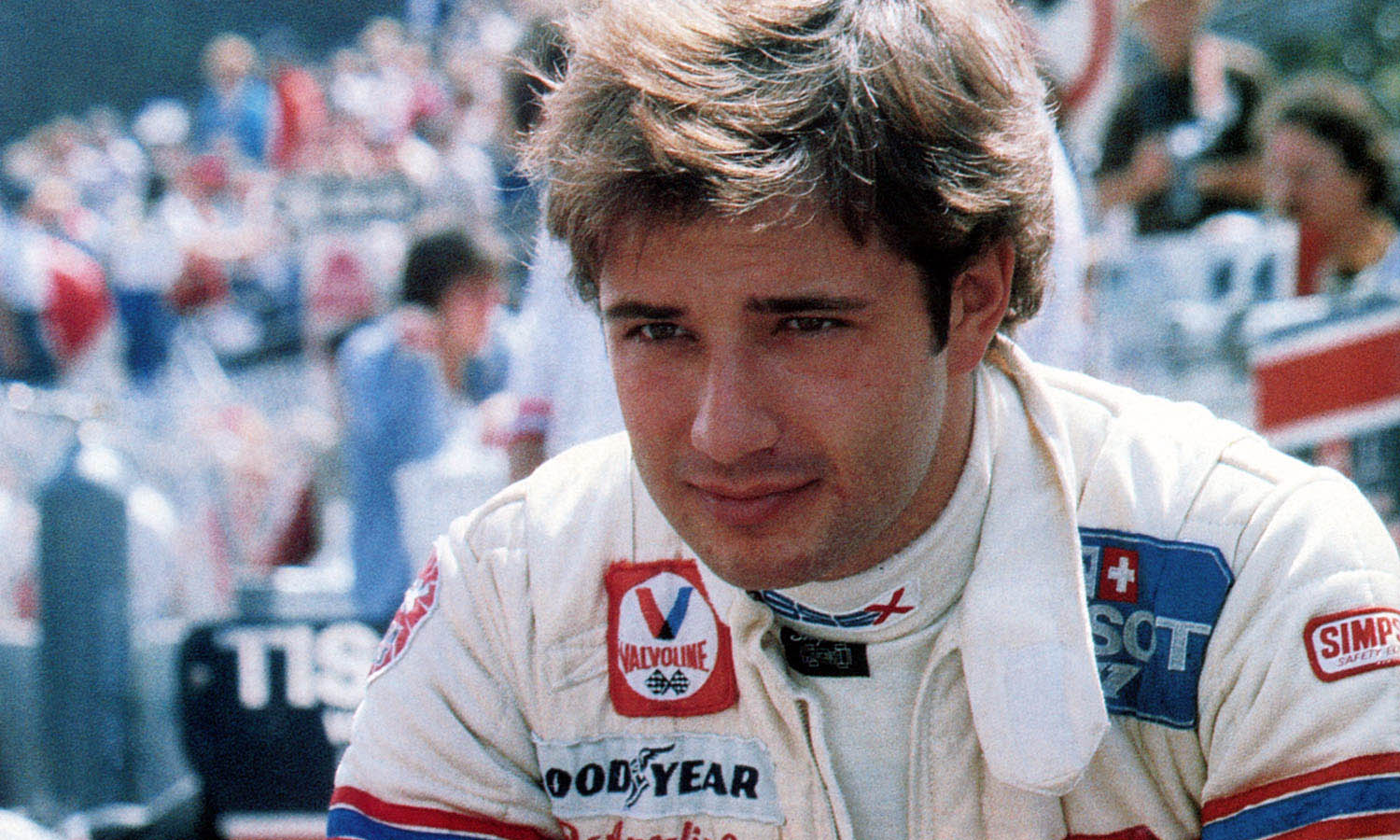

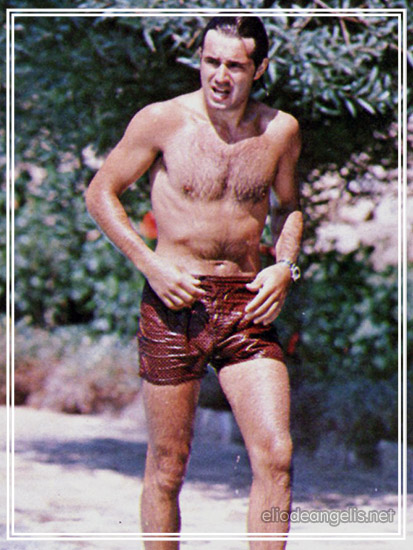

De Angelis is now all of 24 years old, a veteran of four tough years in F1. Physically, though he claims to be no fitness freak, he is slim and athletic-looking. There is a calmness which suggests he could be Swiss rather than Italian, it may be significant that the lovely girl at his side, Ute, is German. They are very attached to each other and converse a lot, even though the common language has to be English. There is a throwaway casualness about his jeans and sneakers. One suspects that possibly, even, he sometimes wears the same shirt two days running. What one can’t perceive from this cool exterior is that Elio de Angelis deserves his place in F1. He’s been with Lotus since the beginning of 1981, its team leader since Andretti’s departure at the beginning of ‘82. As he said, on the eve of his first-ever GP, “you can buy your way into Formula 1, but once your arse is in the metal monocoque, the only person who can help you is yourself”. In four years, he has earned respect as a racing driver. Anyone who still describes him as a “rich kid” (as I once did) is deluding himself and insulting de Angelis. But after three more or less fruitless years with Lotus, where does this more than capable driver go from here?

As he explains it, the answer is not immediately apparent. “My first year with Lotus was one of experience. I managed to get some points and had some crashes. I learned a lot and started to know how Lotus people worked. The second year was the one to put this experience together. I scored more points, but it was the year that the Lotus 88 was banned. All that political arguing is really bad for a driver, you know: when it happens you feel that it is directed at you, personally, not at the team”.

Alas, the controversy over the 88 was not the only reef which de Angelis’ career struck last year. From halfway through the year he seemed to be competing for the affection of his own team with his number 2, the once impoverished Nigel Mansell. It is suggested that Mansell resents his partner’s easier start in life.

Asked about their relationship, Elio thinks hard, but replies decisively: “Nigel is a very difficult man, very hard for me to understand. I think he has some psychological problems: for example, he wants to be quicker than me all the time. It doesn’t matter whether we can improve the car or not. He just doesn’t seem to want to share our solutions when the car is difficult”.

“Part of the problem is the team, because he signed a contract for, I think, three years — as equal number one. The Old Man, Mr Chapman, is working with him. Nigel has a lot of pressure on him, and I think he is not ready for it. In England he is already regarded as a big star”.

“Nigel changed a lot since he came 3rd at Zolder last year. It seemed that he felt he had made it, instantly. I liked much more the Nigel Mansell that I met two years ago…”

Ironically, de Angelis believes that he very nearly made the same mistake as Mansell. In the 1980 Brazilian GP he just failed to catch Arnoux’s faltering Renault and collected an unexpected 2nd place. “I am glad in a way that I did not win that race,” he says with hindsight: “a lot of people would have expected a lot from me then, because I would have been leading the world championship. And without the experience which I have got since then, I would have crashed much more, had more accidents. That is a reputation which a driver in that position should not have…”

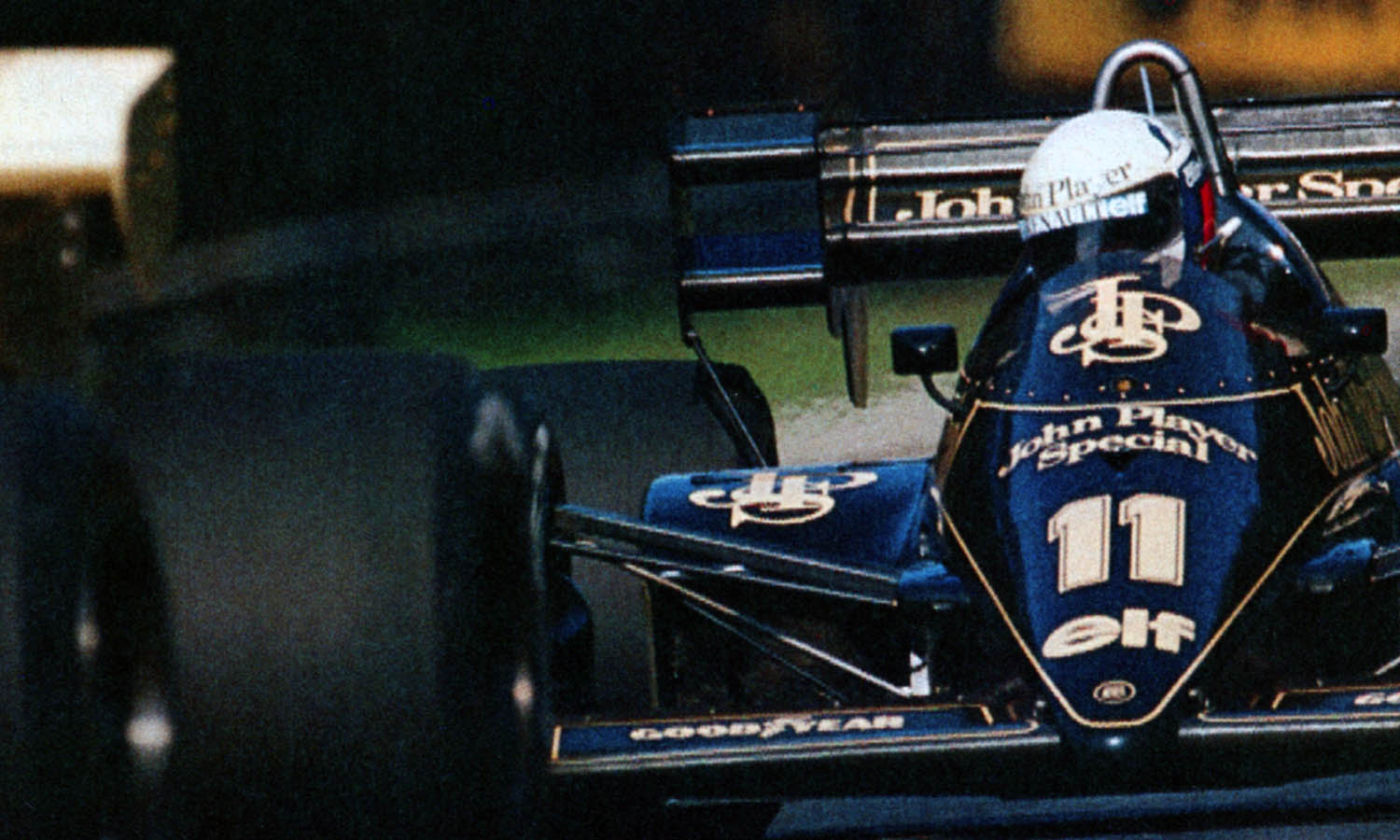

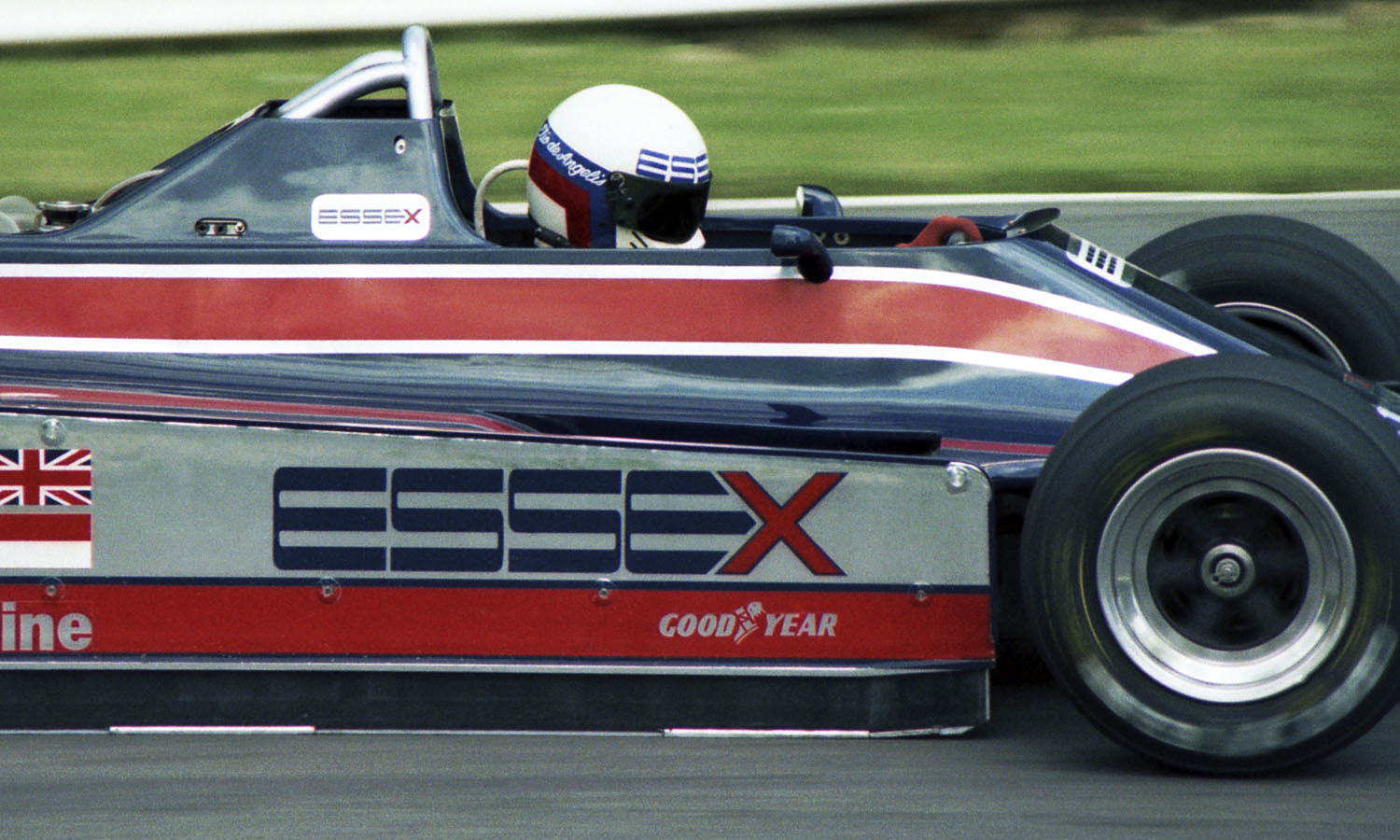

Evidently de Angelis is not comfortable at Lotus. The current season, 1982, should have provided him by now with the victory which continues to elude him. But Lotus’ type 91, a super lightweight carbonfibre chassis clad with the results of some intensive wind tunnel work, looked like a certain winner when it was announced. It has yet to deliver that victory, although at Brands Hatch recently it has shown signs of considerable improvement.

After almost three years with the team, Elio thinks he knows why the car is not a winner. “It is the mentality of the team to want to make innovations,” he says, “not to build a conventional car which copies other people’s thinking. Maybe there are some things on the car which are different because Mr Chapman thinks they will work eventually, like so many other new developments which he pioneered in the past.”

When he comes to look around at the end of the season, he says that he may consider a small, struggling team. As he says, Formula 1 has become more a manufacturer’s playground, with tyres and turbos making whole seconds of difference in lap times, while a driver’s talent counts for little more than tenths.

Perhaps strangely for someone who is endowed with so much of it, money will probably decide where Elio moves or stays as far as teams are concerned. “As with all other drivers, money represents the value that other people place on your ability. The important thing is how much they’re prepared to pay”.

“No, we don’t talk about it a lot, the figures don’t get into the newspapers like they do with football players. Probably there is a mutual agreement between the drivers about this, so that they can negotiate better with the team managers. Yes, I think I probably earn more than Nigel Mansell, I also think I get more than Keke Rosberg, because you have to consider our positions at the end of last seasons. What is important now is that Keke, on this year’s results, will definitely be able to earn more than I do next year.”

“Of course, money is not going to make your life”, he insists, “and especially not my life”. But in one of those peculiar situations which occur when someone is talking about the difference between earned and unearned income, he latches on to cash as the ultimate key to his own self-respect. “It would be significant to other people, not to me, I would have more money to spend, yes. But my goal is not to spend money, it is to win races. That’s all that really interests in my life”.

© 1982 Grand Prix International • By Mike Doodson • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended