"Am I rich? Of course, very rich. My family, at least. But millions never turned a family man into a racing champion. I think I've proven it!"

Translated by this website

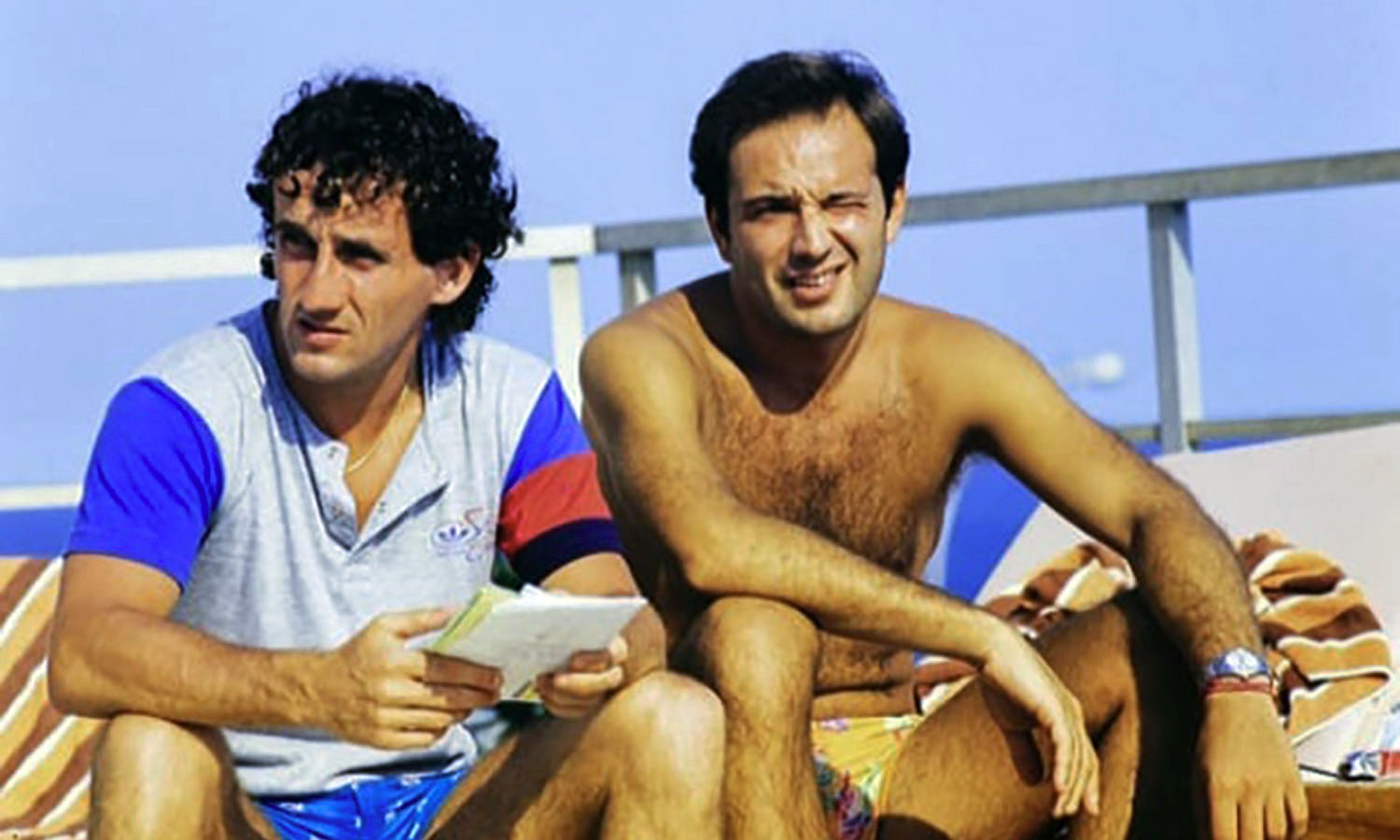

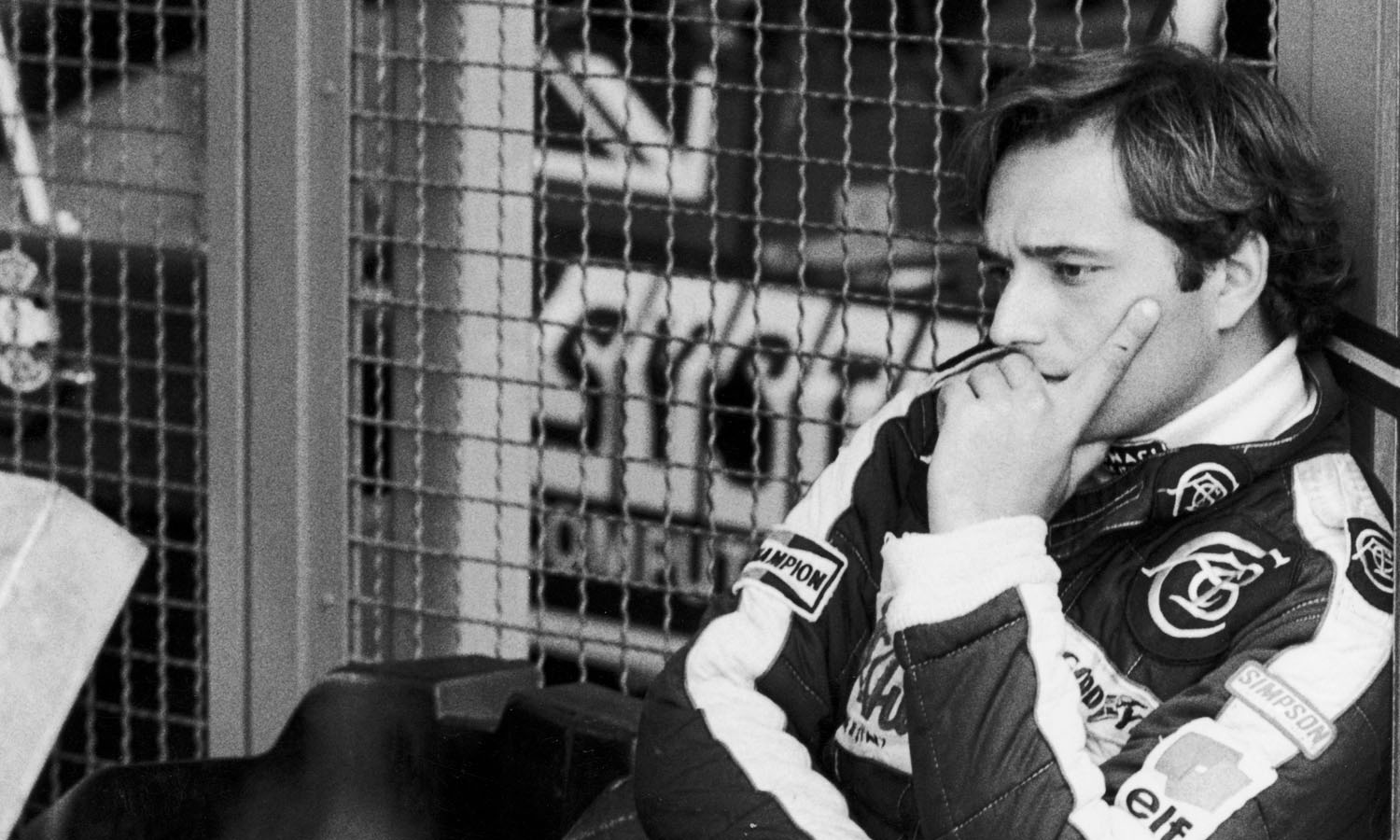

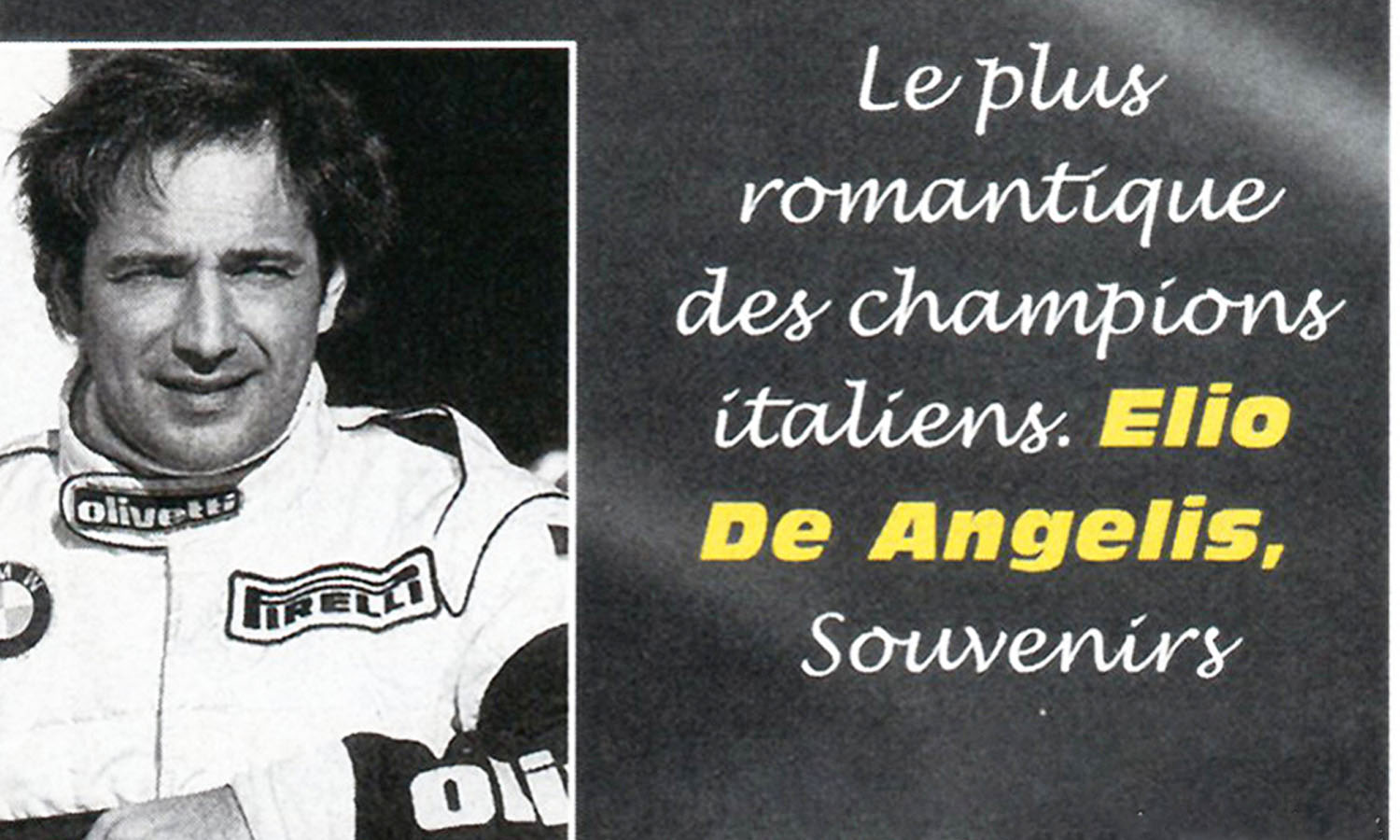

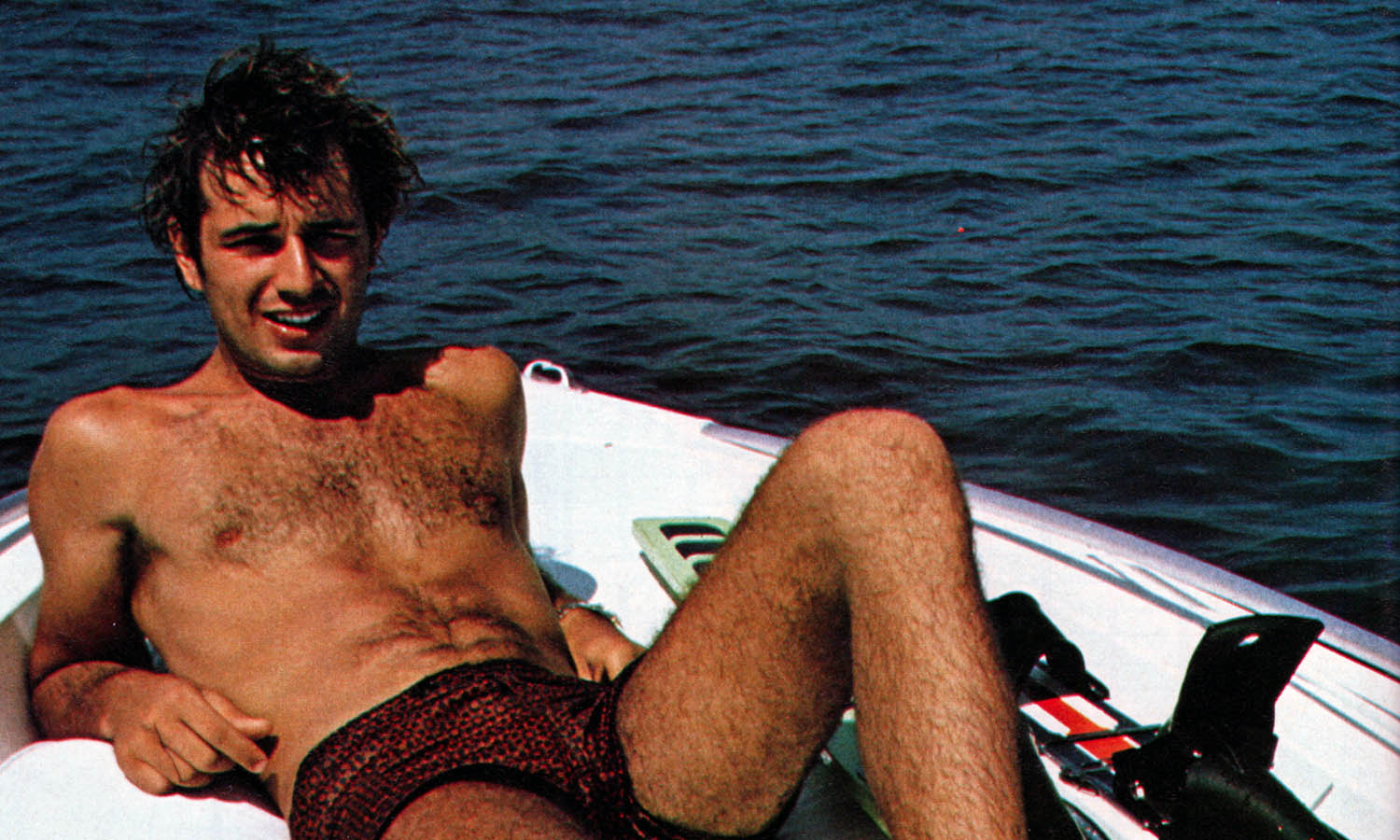

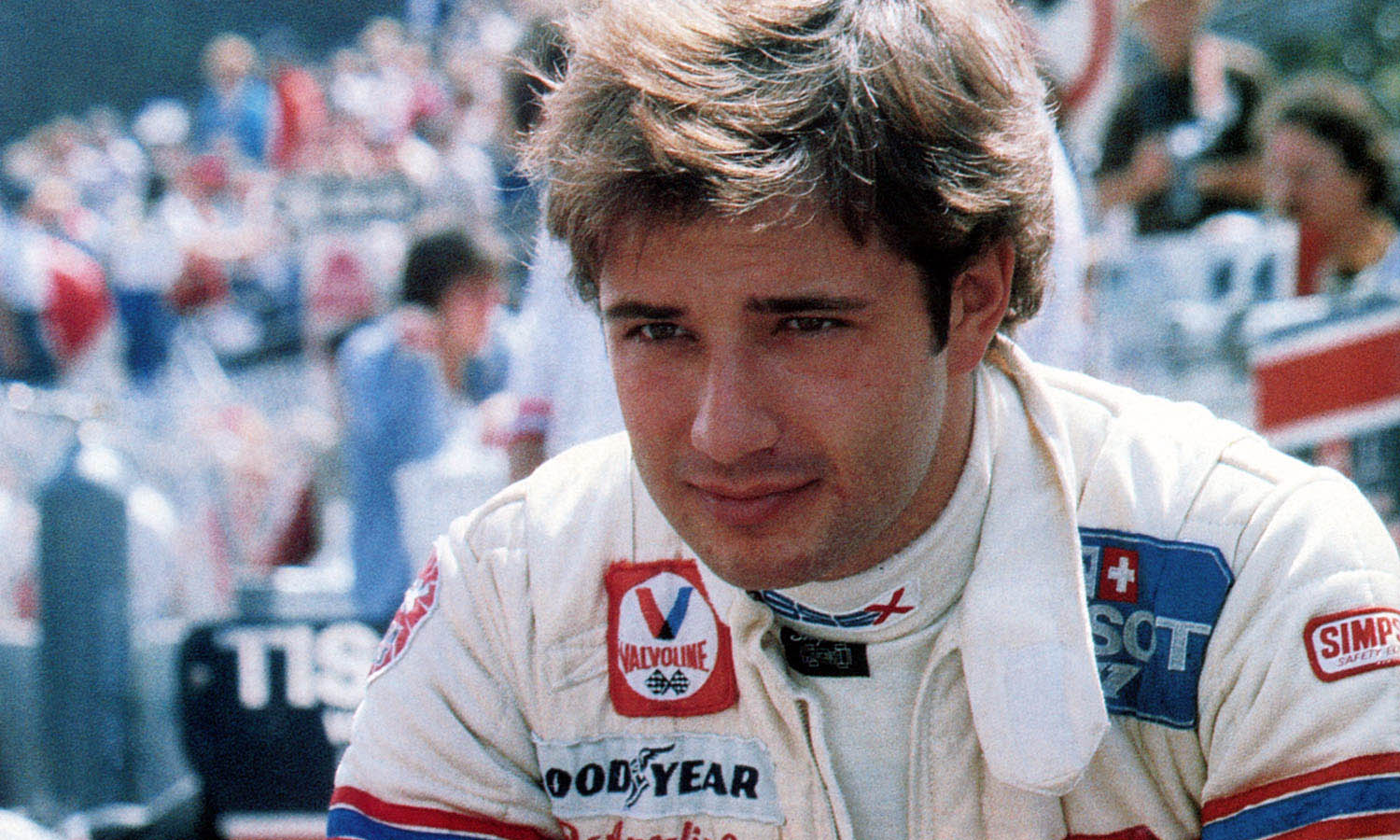

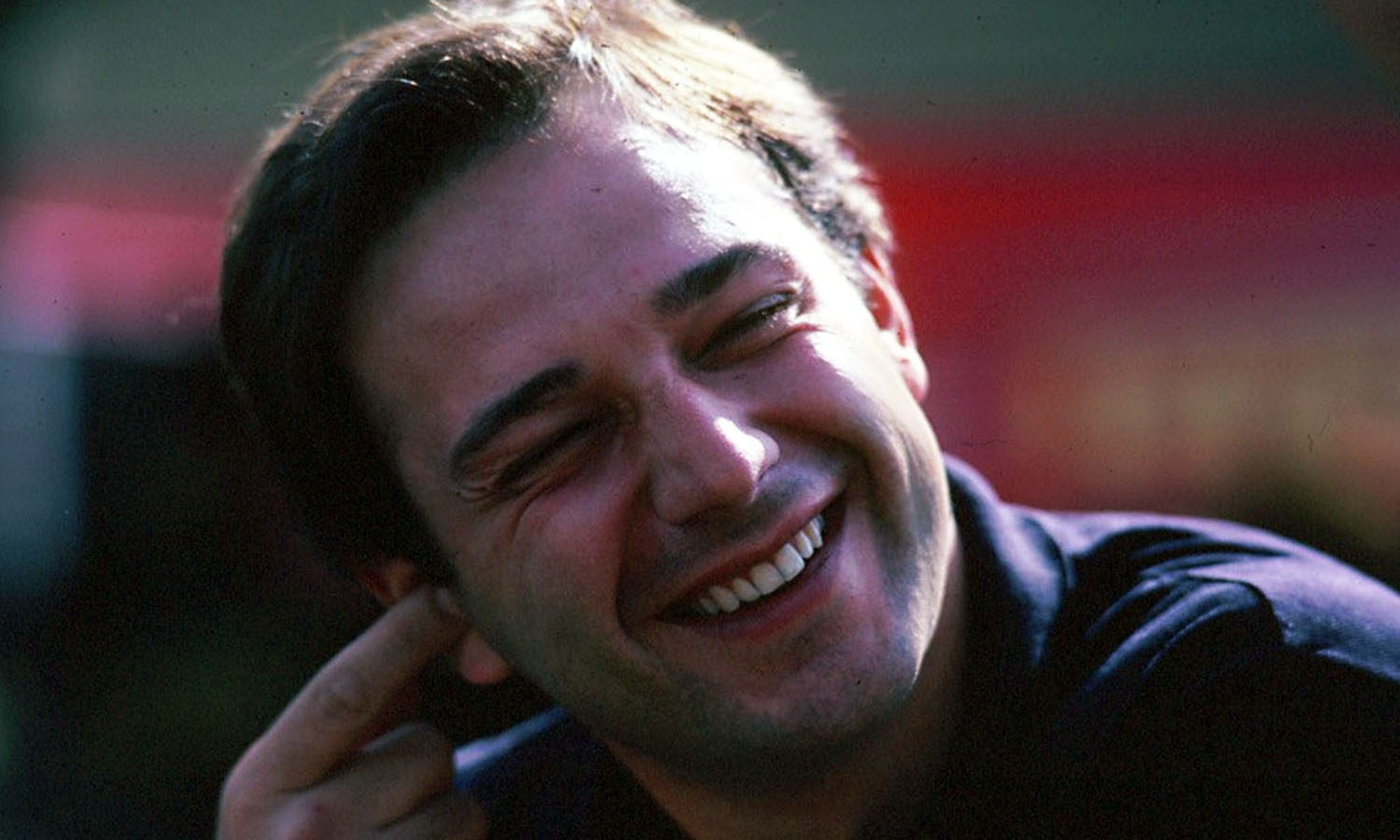

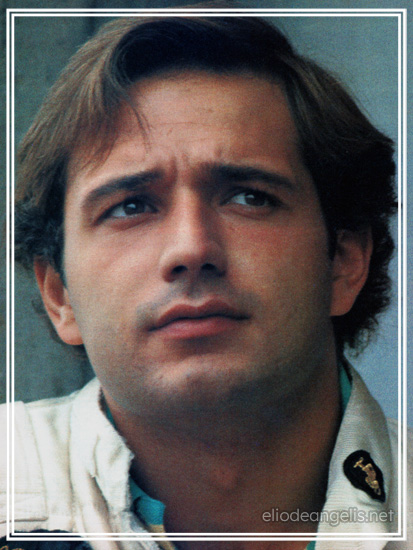

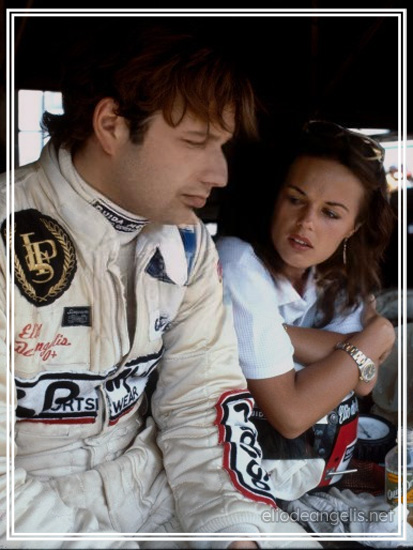

Elio de Angelis? Discreet, taciturn. You won’t often see him talking about the weather with his Italian colleagues. Is this the reaction of a son of a good family? An attitude “inspired” by his playboy physique, who seems to live in the sun of eternal golden holidays? No, not even that. Elio is the epitome of a serious, hyper-professional driver. The antithesis of Don Giovanni. And yet, as our Reutemann specialist, Ineke Flipse, would say, he could… The eldest of four children, two younger brothers and a sister, Elio was immersed in that moving smell of burnt castor oil from a very early age. It wasn’t motor racing, but motorboating. A classy sport that his father, Giulio, has been practicing for many years in the depths of the most “select” harbours of our poor globe. From the height of his ten years, Elio admires and dreams. Sports will play a major role in his youth, starting with skiing, which he regularly practices as part of the National Junior Championship.

Note that the young Roman’s studies are not affected in any way. The theoretical trajectory is as follows: bachelor’s degree and Faculty of Architecture. In reality, after a year of Architecture, Elio will change course and enrol in the Faculty of Law, preparing for an exam he will never take! But hope is not lost.

In 1972, Giulio de Angelis had a different ambition for his beloved son, and motorsports were part of the story. His fourteenth birthday was, of course, celebrated with a magnificent karting chassis as a small gift. Two years later, Elio was crowned Italian Champion. In 1975, the famous Italian Squadra won the World and European Karting Championships. Patrese, Cheever, De Angelis… A real line-up! Patrese was crowned World Champion, De Angelis finished second. The congratulations are numerous but there is no shortage of criticism either. How could anyone not mention the colossal budget available to young Elio? The Parma track was too far away? No matter, De Angelis Jr.’s private tests would take place on the personal circuit that Dad had just built at the foot of the family home. The tires tested during the World Championship event (at Paul Ricard) were not satisfactory? Dad takes the controls of his twinjet and rushes to Italy… Enough to discourage more than one enthusiast! But Elio takes little offense at the criticism and continues his way. His goal? Formula 1, of course.

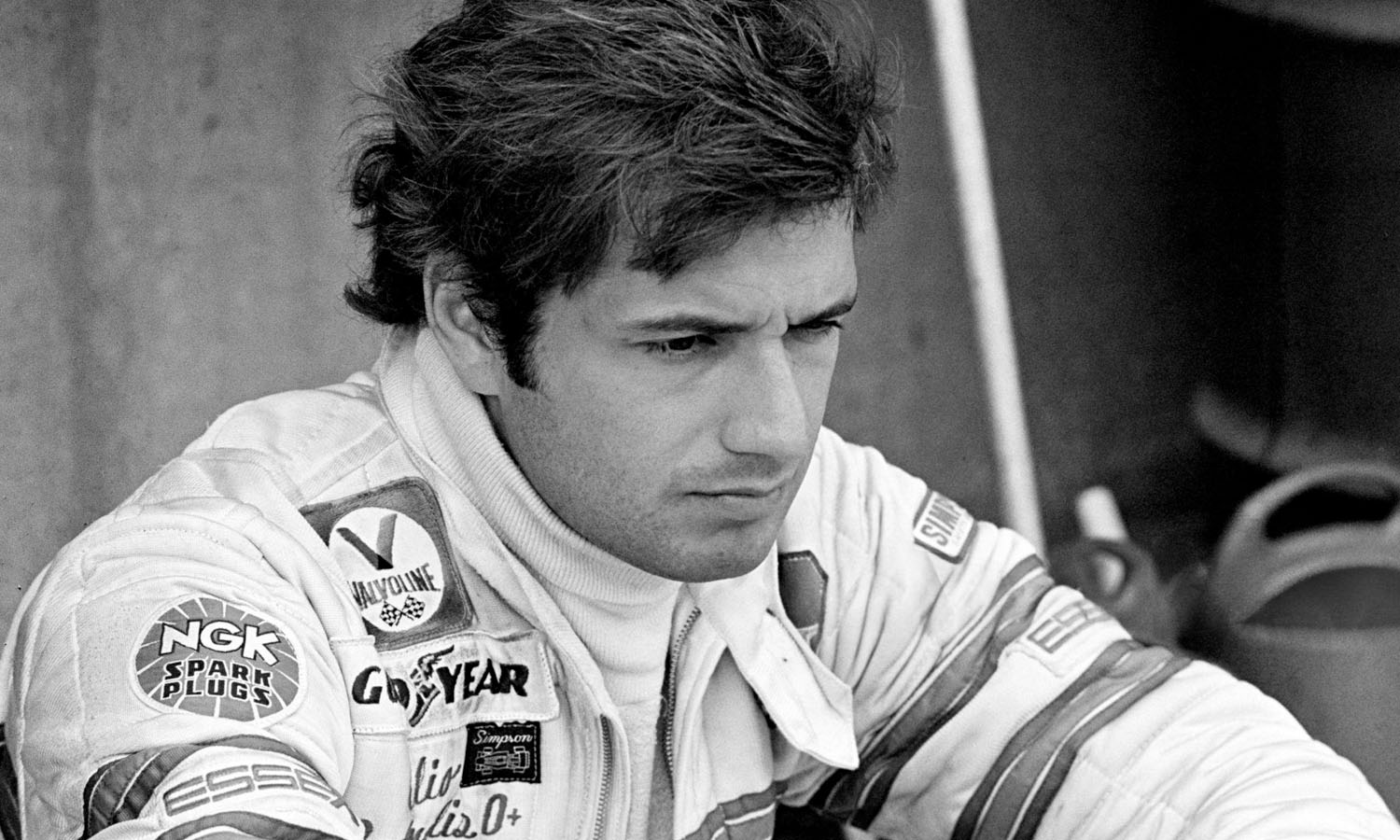

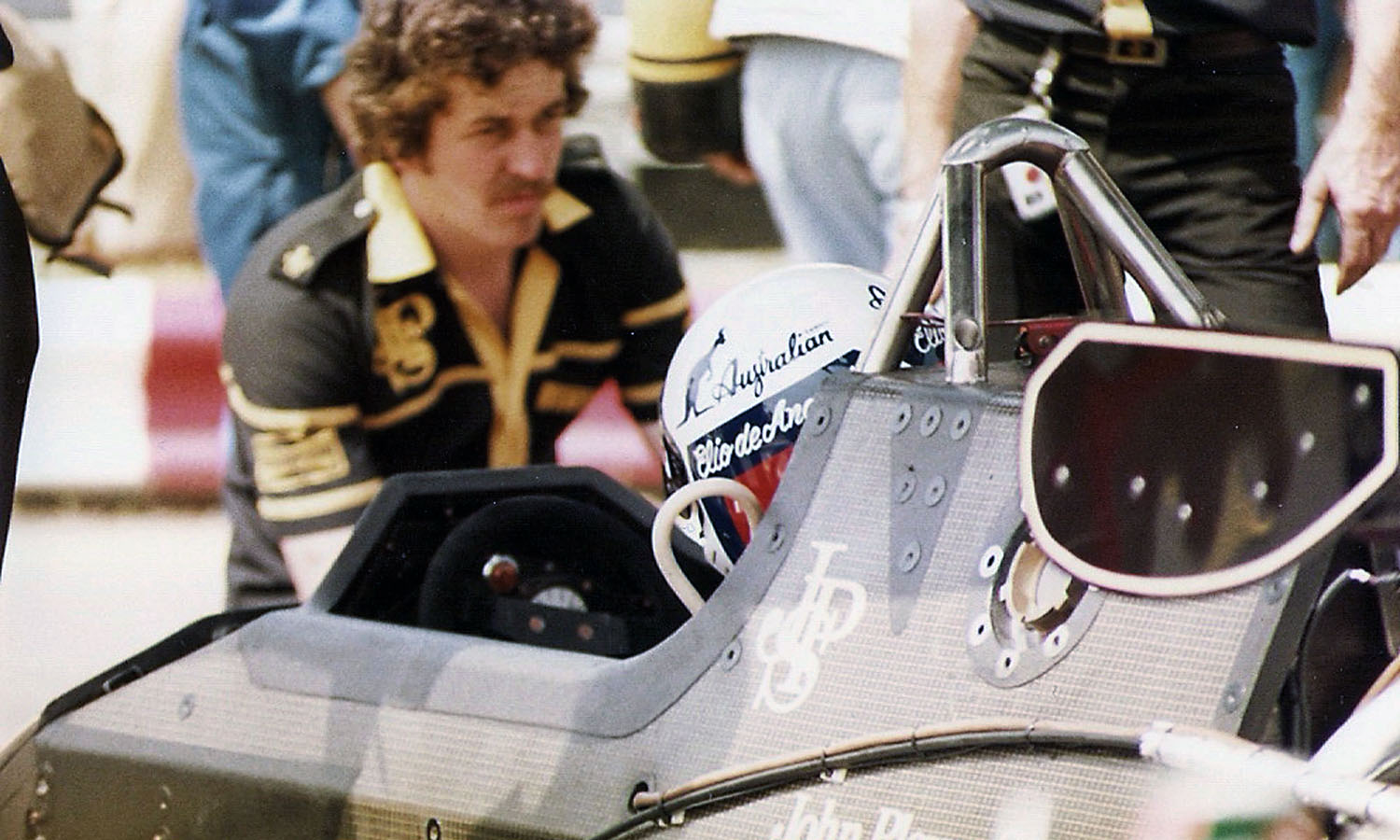

“Most of us come from karting, it’s not by chance. It’s a perfect school for anyone who wants to get into single-seaters and, in 76, I took the plunge without hesitation.” After a few Formula Italia races, Elio quickly turned to F3. “I immediately found myself in my element, at my level, and I even won the title the following year.” That same year, in 77, a Ralt Ferrari was made available to him for the Misano F2 race. 3rd row of the grid, 8th place. The little one is on the right track… For 1978, his unhealthy ambition, consolidated by that of his father, guides his steps towards the Formula 1 boxes, you never know! But no, he must continue his experience, complete his technical baggage and… refine his driving which is still messy. Remember that fiery victory at the Monaco F3 GP! Gaillard recalls it with incredible precision… Finally, the team managers’ eyes began to turn towards him, towards this young man who marvellously combined talent and fortune. Who knows what really interested them! The important thing was that the doors of F1 opened. Oh, not the doors of the workshops but the more realistic ones of the antechamber where big money was discussed. Brabham was interested, forced and coerced by his sponsor Parmalat, but the negotiations came to a halt: Piquet was preferred, to penetrate the gigantic Brazilian market. Ferrari was also interested, given its few Formula 2 races in a very modest Chevron/Ferrari. A test took place on the Fiorano circuit and De Angelis approached the record of the time with the old T3. An overall positive test which, however, will leave the Commendatore frozen. It was Tyrrell’s turn, who succumbed to the enlightened advice of his former driver, Stewart. “After proving I had the A license, Ken offered me a three-year contract, even going so far as to predict the world title for the second season. I signed, we celebrated, and a few weeks later, he called me to explain that the contract was no longer valid, that he didn’t think my license was valid for the following season. In short, it was a big disappointment.”

After this hard blow, which Elio will have difficulty digesting, it is rumoured that Alfa Romeo would be ready to hire him. False alarm… For lack of anything better, the only lifeline the Italian is forced to cling to is the one thrown to him by Don Nichols, Shadow’s boss. From then on, Giulio de Angelis can sleep soundly, his son has just reached the Sacred Temple he has always dreamed of. An expensive dream? “My father helped me a lot, it’s true,” Elio admits, “and I don’t try to hide it. He gave me the opportunity to start without too many problems. For a young person embarking on this adventure, it is practically impossible to land a serious sponsor without a track record. I admit that with his help I could already consider myself a professional driver, a real one. Note that the sacrifice made by my family did not exceed a certain limit that my father had set for himself.” To tell the truth, the son’s commitment to the Shadow team wasn’t the most expensive investment: $3,000 guaranteed for the first eight Grands Prix. Then, it was at the discretion of the boss and the withdrawal of Danny Ongais only precipitated things. De Angelis became the house pilot. Nevertheless, tongues were loosened, leading Elio to adopt a cold, distant behaviour, even and especially toward his own Italian “friends.” Financial aid, distorted game, he hears here and there, and this jealousy annoys him “The game is distorted? Yes and no. With money but without talent or motivation you don’t go far. Hector Rebaque gives me a perfect example. Thanks to his personal fortune he was able to find a small place in Formula 1 but because of it he was unable to make a decision the day he had to choose between motorsport and the easy life. I think he placed too much importance on his well-being, his personal comfort. For him, salvation could only lie in giving up and returning to Mexico. Money and ambition are two completely foreign contingencies.” The proof? After negotiating his entry into Shadow, he “worked hard” throughout the season, managing to win the title of best rookie of the year thanks to a hard-fought 5th place during this epic and wet Grand Prix of Watkins Glen 79.

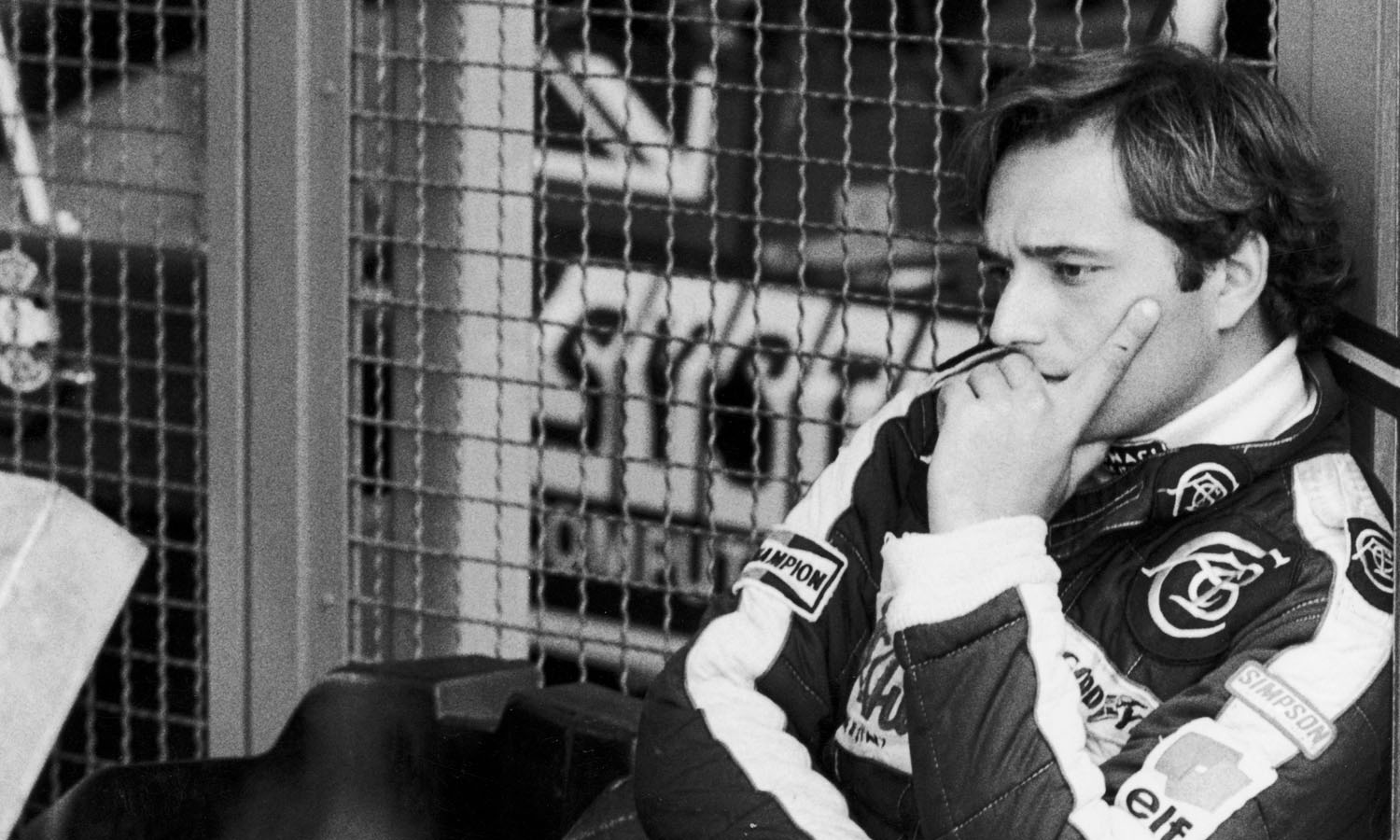

“That Shadow era was very funny and bizarre,” Elio admits today. “At first, I was enthusiastic because I was so happy to be in F1. In fact, everything happened like with a team that had no money. When I arrived at their place, they showed me their files and the potential presented impressed me. I quickly understood the day I realized that there was only one engine for testing and racing! It may have been a good project, but the lack of money didn’t allow it to be developed, no private testing, no serious technical discussion. I remember that the only major modification was the one at Silverstone: new sidepods. I gained 1.5 seconds in one go. But that was the only improvement of the year.

Yet, it wasn’t that bad, this Shadow! But those problems keeping it in a straight line!”

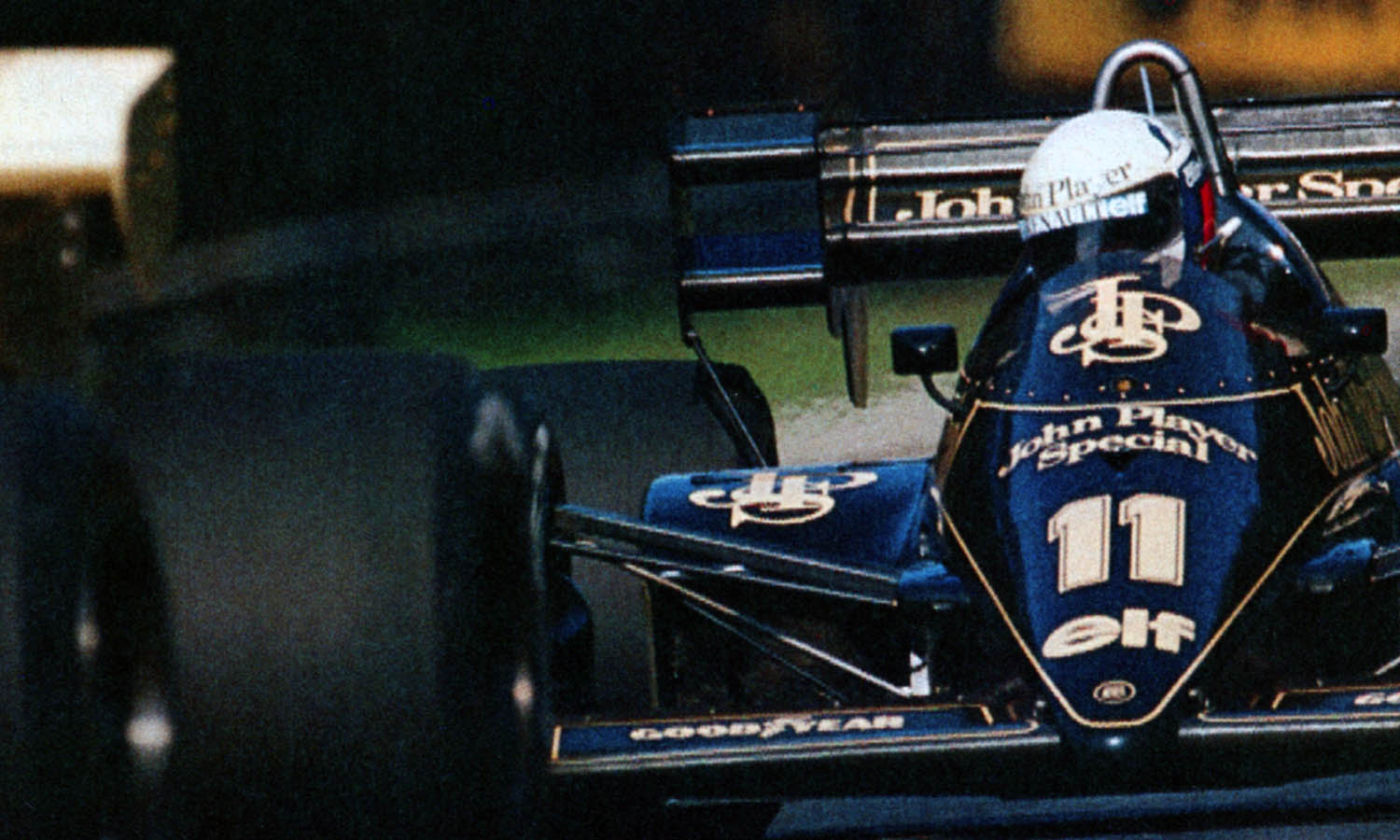

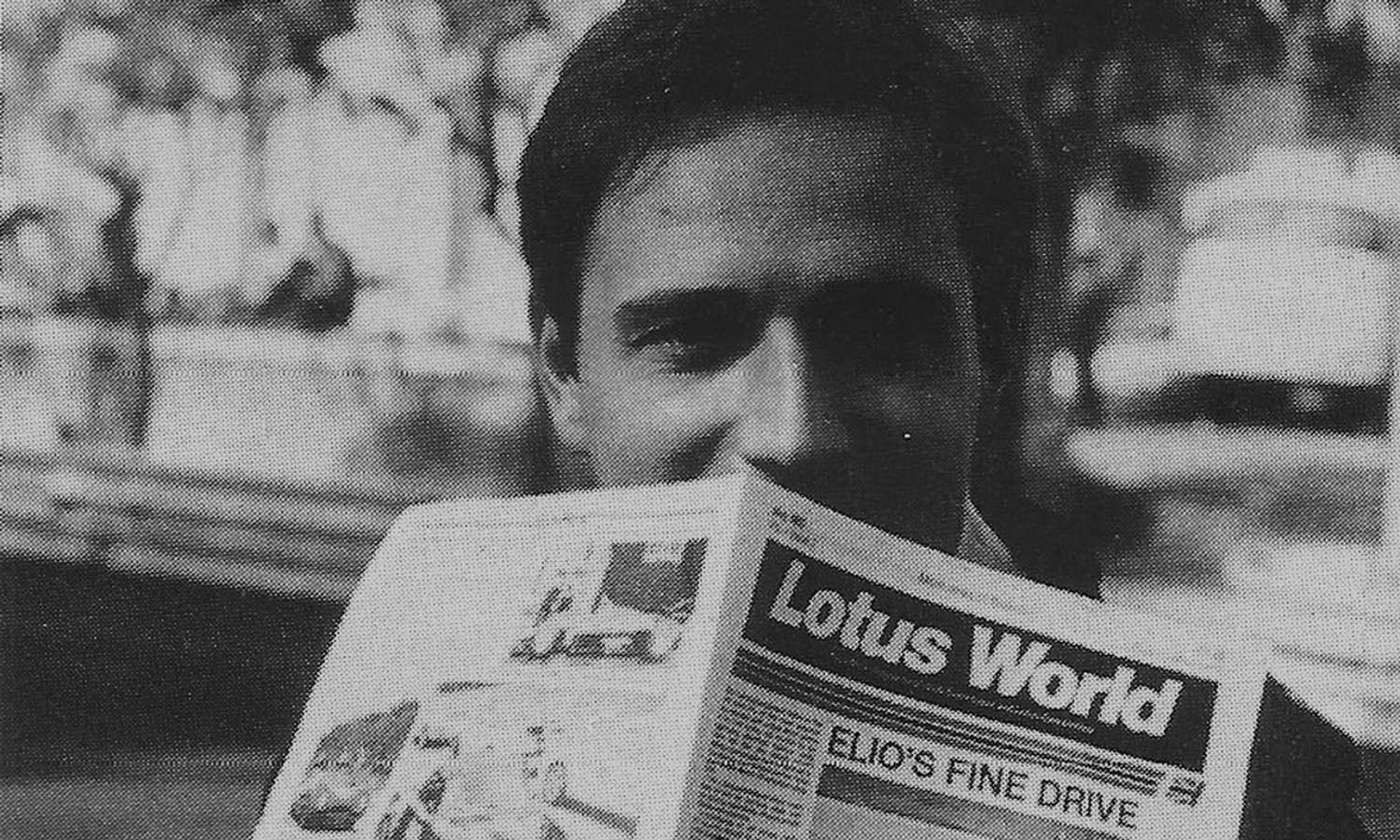

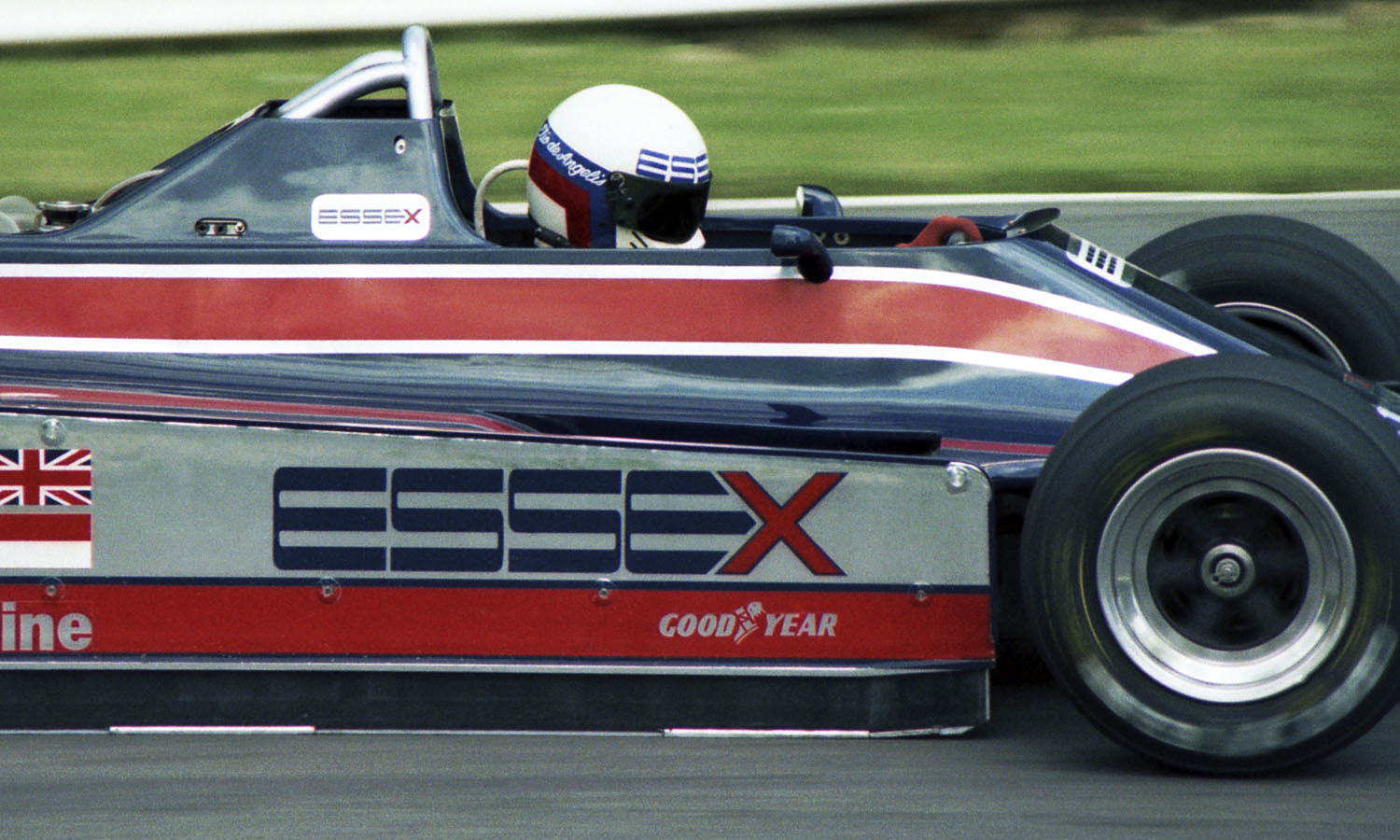

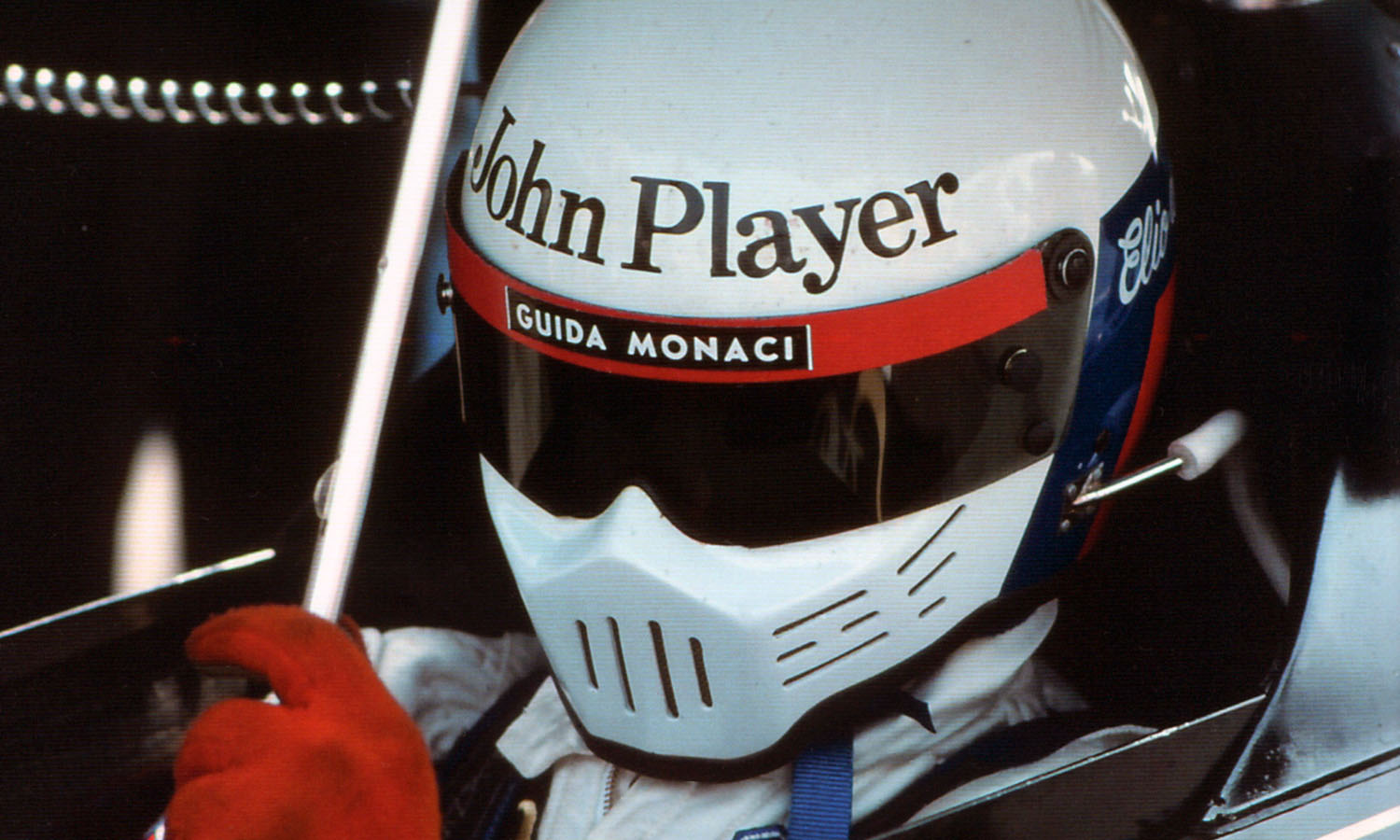

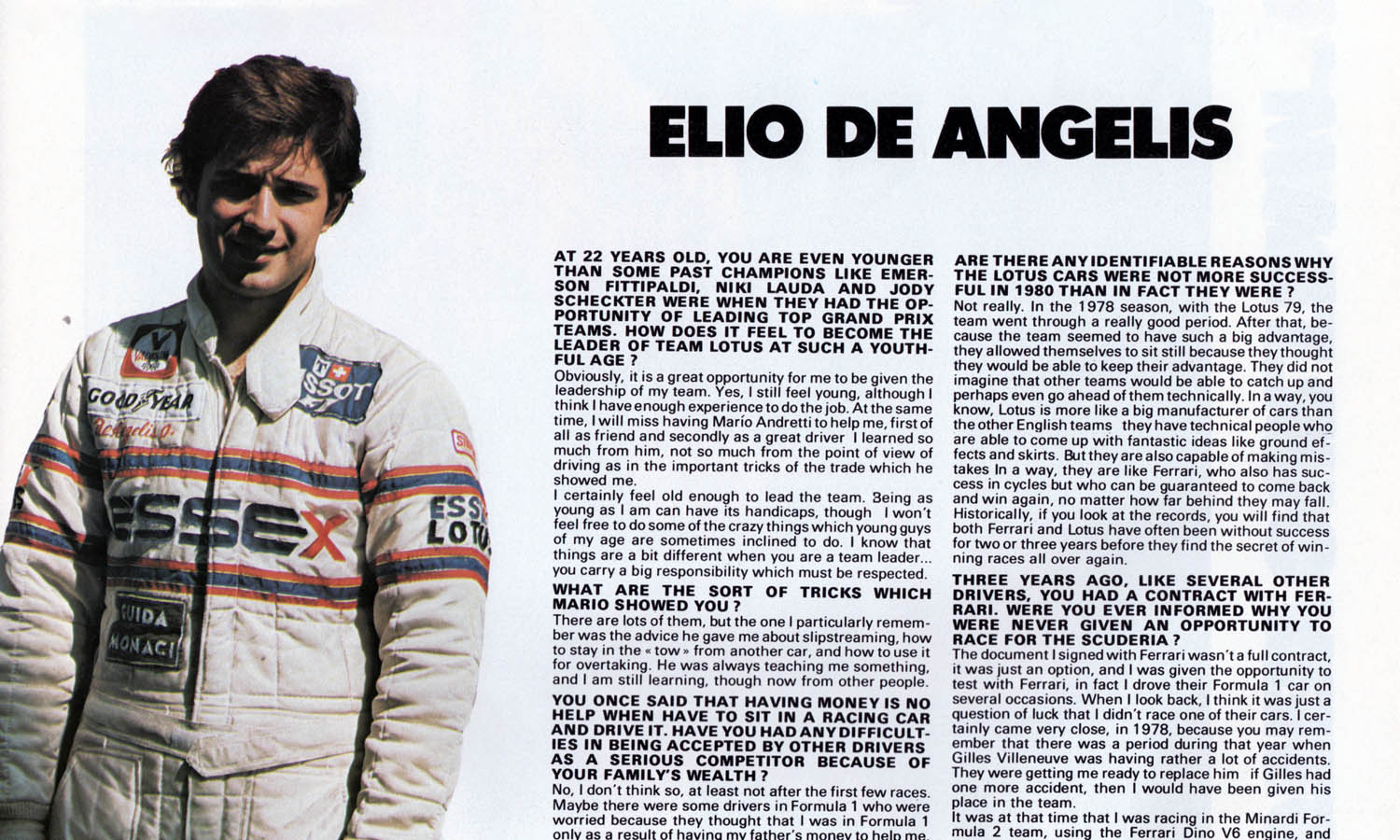

Fortunately for him, his efforts did not go unnoticed, and Colin Chapman was the first to acknowledge this. Reutemann left the Lotus team with a few heartburns, and the young Italian did the trick. The main thing was there. “A discreet season, but not without problems. The Lotus lacked rigidity; the team lacked unity. I had high hopes, especially with my second place in Brazil. I thought the start to the season was divine, marvellous. However, towards the middle of the season, these rigidity problems took on worrying proportions; the chassis could no longer withstand the aerodynamic constraints, and Chapman had to make the most technical reversal of his life. He then made some makeshift “tinkering” that turned out to be almost not bad at the end of the season. 6th place in Italy, 4th in the USA East, and 7th position in the World Championship. We had all come a long way!”

There is, however, one small detail that Elio omitted to mention: how can a young driver join the prestigious Lotus team? “My time at Lotus was indeed quite complicated but not because of Chapman. At the time I was under Shadow contract, for two seasons (79 and 80) and it was out of question leaving Shadow after a year. My negotiations with Lotus lasted a very long time and we finally reached an amicable agreement • Chapman paid me for this first season with him and this money went to Shadow to compensate them for my early departure. So, in 80 I didn’t earn any lira! It was the only way to leave a bad team to join a good one. This transaction made me think a lot, but I think it was a wise investment. In any case, I had little choice. Shadow no longer possessed a single penny, owing me four months’ salary, and couldn’t offer me the slightest promise of a future. This future would prove me right. The team would disappear, body and property.

Elio speaks slowly, weighing each word, but freely. Bringing up these negotiations is a perfectly natural thing to do. Mind you, this kind of questioning is no stranger to him! Sitting on a low concrete wall, he assiduously puffs on his cigarette, paying no attention to the splendid race boat bobbing with the lapping waves. Yet, as this discussion unfolds, several details escape us. What can the relationship be like between an old sea dog like Chapman and a newcomer?

How can we allocate a budget to this young person without a professional business card, and, moreover, a very comfortable one? “No, no,” Elio protests, “Chapman wasn’t at all concerned about this characteristic. He paid me my first season, cash on the nail, and as I already said, I immediately endorsed the check to send it to Shadow. Three months later, he offered me the ‘81 contract.” The dream was complete, even if the boss-employee relationship was not what he had hoped for.

“Chapman is a very complex man, very difficult to understand, and two years later, I still have a lot of trouble understanding him. During the winter of 79/80, it was the first time I spoke to Master Chapman, and for him, I was only the 33rd new driver to arrive on his property. Like many famous racing bosses, he has seen many young drivers, good or bad, come and go, and I think he tries each time to build a wall between himself and these “outsiders.” He waits for proof. At that time, our relationship was rather fresh! The day he carried out his assessment, he must have realized that his recruit corresponded to his expectations, and, piano-piano, the atmosphere relaxed. He became more human, he took me into consideration, and from then on, I devoted myself to winning the title.

Without his graces, I think it is useless to think about it. Today, our relationship is good. Not only that of boss/driver, but also that of man to man. We even manage to have fun! Sometimes.”

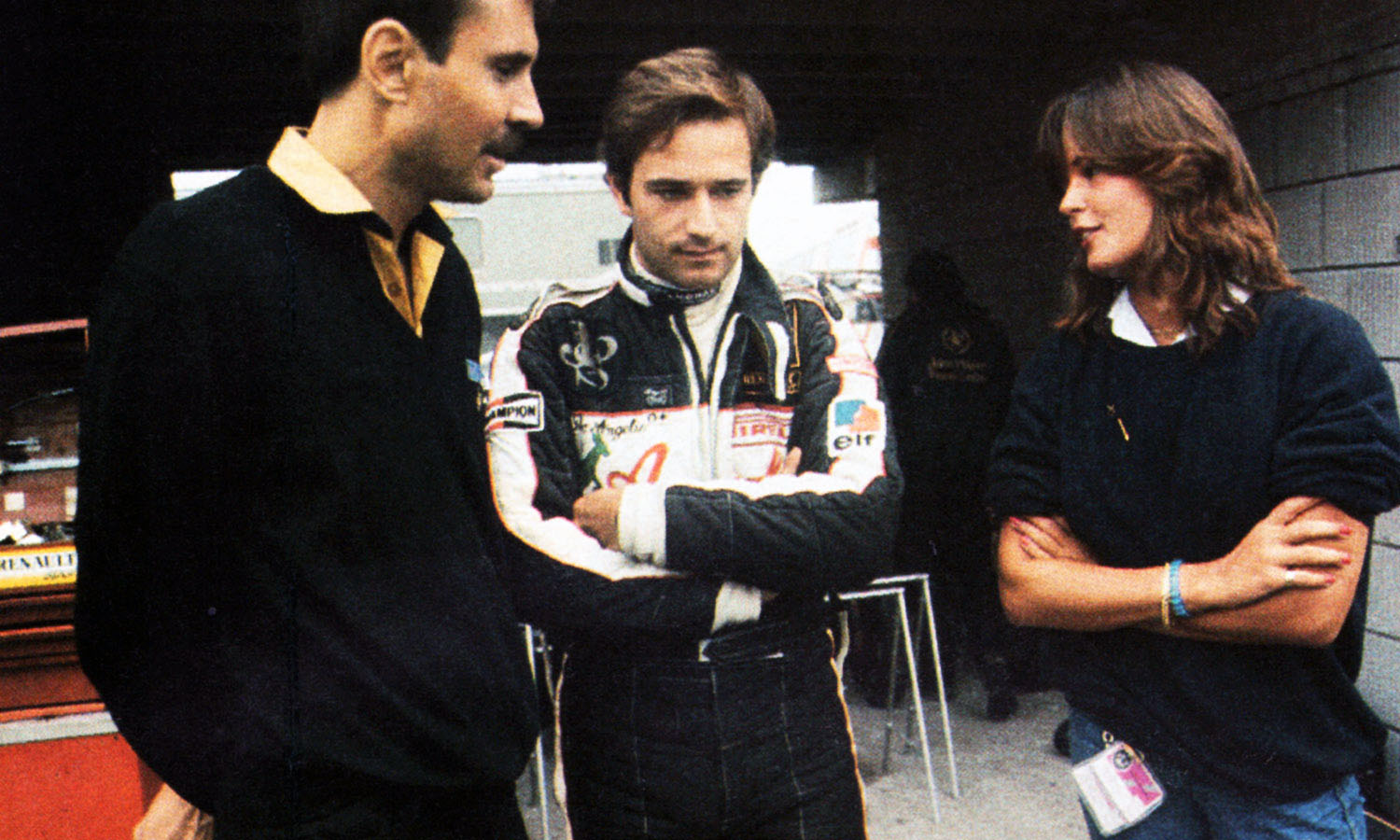

On this same date, at the end of the 80s, Andretti decided to leave England to join the Alfa clan and here is our young and handsome De Angelis wearing the first driver’s suit. A departure he still regrets today. “It’s true, I regretted Mario’s departure, he was the best teammate I ever had. Or Jan Lammers. Although with Jan the situation was different, we were two young people without experience within a team from which we didn’t expect much. The understanding was natural. Mario never played the great champion, the star as he could have done with me. On the contrary, he taught me a lot about the trade, obviously wasting a lot of his time. He didn’t have to do it given the experience he has. You know, I’m convinced he would still hold his place today.” The seat left vacant by Andretti doesn’t remain vacant for long. The time has come for the in-house test driver, Nigel Mansell. An arrival that De Angelis only half-appreciated during the first confrontations. “Nigel is a very courageous guy and he’s doing well. The only thing he lacks is foresight. That will come with experience. Last year, he wanted to prove his capabilities and show everyone that he knew how to go fast. It was bad for the team because we were in technical difficulty. Going fast without trying to resolve the development issues is useless. On the contrary, it’s necessary to have two attentive and consistent drivers, who don’t spend their time attacking in all directions. The day you analyse the behaviour of your car, when the engineers know where they are, you go very fast, and what’s more, without exceeding your limits. It was his first year of racing, so it was a forgivable mistake. He understood perfectly.”

However, the Mansell-De Angelis relationship has suffered from a sort of unease since Chapman’s eyes cast marvellous glances at the young Englishman. At the end of the ‘80, the soft eyes were for De Angelis, and not only those of Colin… But the latter knew how to convince. The salary was increased, the first driver position was offered, and plans were made for the 88 comet. Little by little, the atmosphere at the start of the season changed, and Colin fell under the spell of Nigel’s 3rd place in the ‘81 Belgian GP and remained there. Even though it was his best place to date. “When Mario was at Lotus, I was often asked to give him my car. I accepted because he was the first driver. Today, I sometimes waste my time in the pits, waiting for endless adjustments while Mansell jumps out of his car to the mule every five minutes. ” We must face the facts… Ultimately, if the boss didn’t maintain this little rivalry and the privileges that go with it, Mansell and De Angelis would get along well.

Friend-friend? Difficult to judge “Friends aren’t chosen, and I wonder if the F1 world is truly sincere. At the driver level, because elsewhere… A driver’s life is necessarily changed by success. Mine will change; that’s for sure. I have very few friends, and I think the life of a champion is that of a loner, the owner of a watertight personal cell.” A philosopher in his spare time? No, Elio in no way possesses this fibre. At most, he tries to judge himself. “It’s still risky! My ideal would be to be like Lauda, to drive like him, even if he doesn’t give up anything to the spectacle. His victory at Long Beach surprised me. Astonishing! I’m proud to have to fight against him in cars that are almost equal.

When I saw him for the first time, he was in a Brabham and I was in a Shadow, I had trouble imagining that we would meet again one day. A funny character who is good for F1.

But let’s get back to the driver’s professional life. The judgment he makes on his boss’ work. Starting with the famous Lotus 88 double-chassis: “It was a car with interesting potential, but it was poorly developed technically. I even think it was poorly built. However, I remain convinced that it was disqualified for ridiculous reasons. The hydraulic “tricks” that the FISA accepted that same year were far more outside the regulations than the 88, which represented a sensational technical innovation. We never understood the official procedures, and this was a huge disadvantage for us, a real blow because we were forced to rebuild new cars. Abandoning the development of one model to move on to another means losing a lot of money and even more time. From there, we moved on to the 88B, with its delayed development.” Look at the cars that were doing well at the time: the Brabhams, the Williams, cars that had 2 or 3 racing seasons. It’s not by chance. Basically, the faults of this 88B were its weight and a top speed that was far too low: 267 km/h! 18 km/h less than the Williams, it’s incredible. We never understood why. It was a bad car, a bastard child of the 88 born from a painful birth. Fortunately, the Lotus 91 is a real Lotus, light and competitive. There are no miracles; if we want to keep up with turbo engines, we must have a light car. For Zolder, we have achieved an optimum development that should allow us to win a Grand Prix very soon. At least that’s my hope…”

Competition between turbo engines and Cosworth engines, the complete disappearance of suspensions, constantly decreasing weight, excessive ground effect… the performance of an F1 car no longer seems to depend on the qualities of its driver. Rosberg doesn’t mince his words and sincerely assesses his role at 25%, sometimes less! “Keke is exaggerating. Okay, the driver’s role has decreased compared to that of the mechanics, but it’s around 60%. If you take the ten best drivers of the moment and give them a great car, eight of them will win. You put them in a bad car, these eight will get on the podium after 6 months of work, achieving perfect tuning that I consider essential for victory. The gap between these drivers will be small, one will favour top speed, the other cornering downforce, but they will win. The 60% I’m talking about is therefore made up of the 20% Rosberg is talking about, plus 40% that I put down to the research and development work during private or official tests. A crucial task.”

Obviously, for De Angelis, success requires other ingredients that unfortunately cannot be ignored: the quality of the equipment, the technical team, the driver/engineer understanding and, perhaps this is the strong point of this success, motivation.

“The motivation that drives me to win the world title is the same that drove me in F3 to move up to F1, it has even changed, moving towards a compromise where teamwork has taken on more importance. Going fast is no longer enough.”

Elio thinks, hesitates, takes a panoramic look at the fabulous scenery that surrounds him. “Feeling good about yourself is also part of the game.” And that’s where the problem lies. Nature has given him admirable gifts. Wealth, intelligence, health—he succeeds in everything he undertakes, but none of his efforts are recognized. Even the specialized Italian press seems to ignore them. Elio’s greatest regret. Money? “Yes, it may be the source of a certain jealousy. I don’t hide the fact that my beginnings were easier than Arnoux’s, but I had to do things that most well-off people would have refused. $100,000 is no substitute for motivation or experience, and it won’t fix your chassis.” Unless this jealousy isn’t really jealousy at all, but rather that old Italian rivalry that has pitted Black Italy (the northern Italy) against the southern Italy for centuries. The rivalry Giacomelli/De Cesaris, Alboreto/De Angelis…

Meh, isn’t the fate of a champion that of a loner? Life goes on… Divided between bustling Rome, luminous Sicily, and grey England. Downhill skiing, water skiing, soccer, tennis, spearfishing, and music. An excellent pianist, De Angelis spends many hours at his favourite keyboard, and some of his creations have been transformed into pleasant pop songs for which his family is the only audience. Too bad. Good food would also be an interesting pastime if its repercussions didn’t reach proportions that the scales make worrying. Ah, cruel sacrifices!

Wouldn’t fear be even more distressing? “Fear and dreams are intimately linked to a driver’s life. Two realities that exist deep within each of us. It’s human. I deal with fear because it assails me after every mistake. As for dreams, they also live within me constantly. Without them, I would stop racing, right now.”

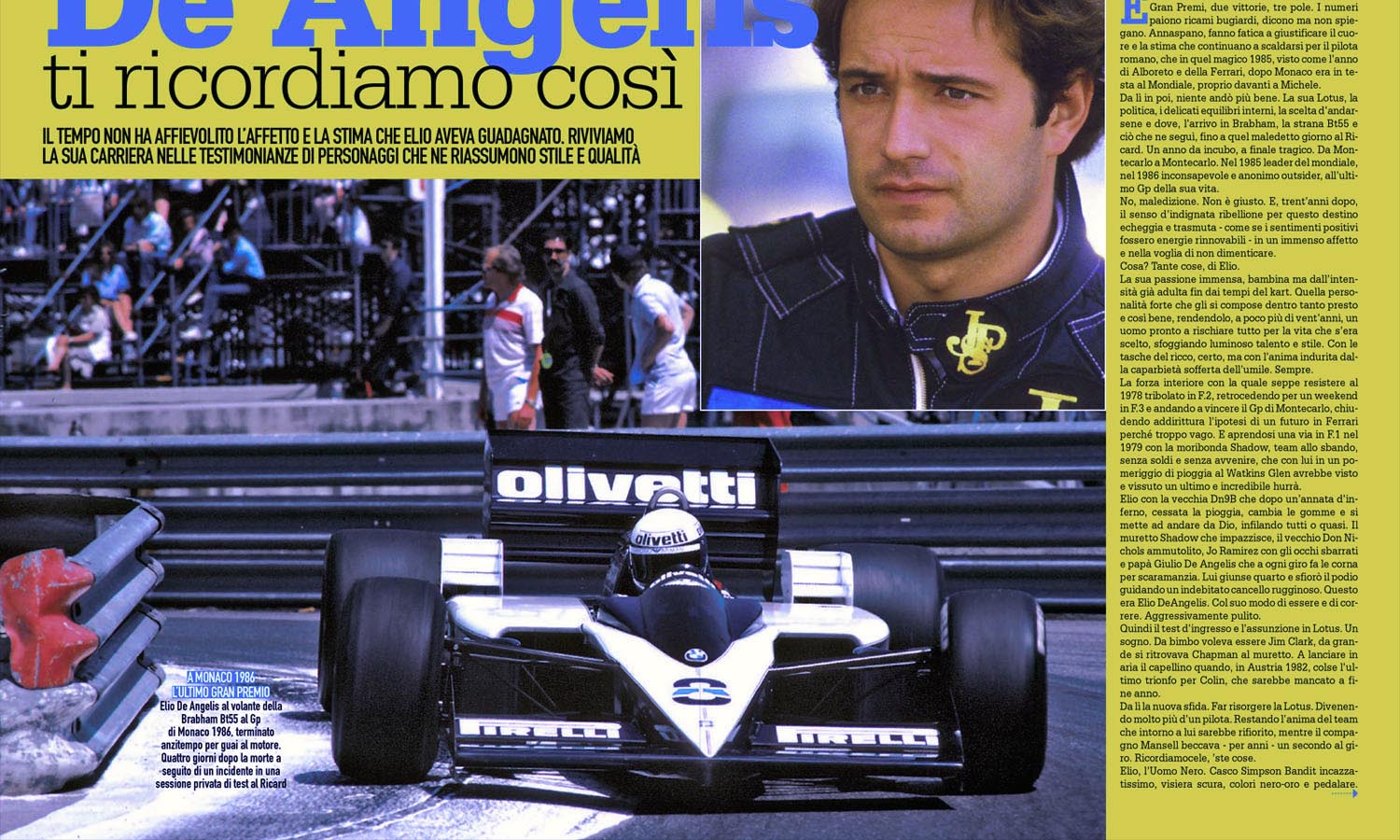

© 1982 Auto Hebdo • By Patrick Camus • Published for entertainment and educational purposes, no copyright infringement is intended